About the Writer:

Mitchell Chester

Mitchell A. Chester, Esq. is a trial attorney licensed in the State of Florida. In practice for 37 years, he is focused on identifying and seeking solutions to emerging legal and financial issues created by sea level rise (SLR) and climate impacts.

Mitchell Chester

Urban waterfronts as ticking time bombs

We do not create ethical urban waterfronts. Instead, we produce coastal buildings to emanate toxicity. With each construction permit, local governments and private landowners are creating conditions that will further acidify our endangered oceans as sea level rise (SLR) advances to permanent inundation.

There is no greater long-term responsibility facing today’s urban waterfront planner than to formulate strategies to prevent disastrous bleeding from inundated structures in areas where the invading seas will overcome the built environment.

Utility connections, electronic components, underground storage tanks, paints, sealants, solvents, cleaners, adhesives, glues, electrical grids, sewer systems, septic tanks and drain fields need to be insulated so their chemistry does not cause environmental harm when covered by water.

With each new edifice, our generation is leaving a legacy of neglect. No reasonable society would further acidify the oceans, but that will happen as seas overwhelm coastal shores, allowing the escape of dangerous lead, mercury, formaldehyde, heavy metals, insulation fibers, PVC chemicals, perfluorinated compounds, fiberglass, wall foam, oils, lubricants, flame retardants, toxic electronic wastes and other threatening building materials.

In the absence of secure demolition, what we build on dry land now will poison the seas of tomorrow. Yet, we keep building. According to CraneSpotters.com, as of December 29, 2014, up to more than 300 new South Florida condominiums are being constructed or are on the planning board. While they are required to have elevated foundations, there are no standards to insure those structures are ready for inundation within the average 30 year mortgage span to 80 years, or in some areas, less time. According to RiskyBusiness.org, in Florida alone, “between $15 billion and $23 billion in current property will likely be inundated by 2050 from mean sea level rise…”

We are not ready.

Property owners are taking little, if any, personal responsibility for making sure their condominiums, office towers, government buildings and homes can sequester noxious substances when the time comes to abandon buildings and retreat from today’s threatened and vulnerable areas. To amplify the problem, older properties are poised to release, unchecked, asbestos and volatile organic compounds into ocean currents for unbounded distribution.

The mechanism of the built environment infecting our oceans is already a reality. According to the Guardian (December 28, 2014) “Almost 7,000 homes and buildings will be sacrificed to the rising seas around England and Wales over the next century…” The paper adds, “Over 800 of the properties will be lost to coastal erosion within the next 20 years”. In 2013, 1,400 homes fell into the ocean due to a ‘huge tidal surge’ which affected England’s east coast.

What measures can we take? One can envision a new industry of environmental inspectors and engineers to consult with stakeholders on how to adequately “seal” and prepare homes, offices, schools, hospitals and public infrastructure in the aftermath of hurricanes and advancing salt waters. Such experts are needed before construction begins, and once again when the building is no longer deemed habitable by public health authorities. Done right, such an industry will prompt the creation of thousands of jobs globally.

Governments need to ask not just what happens when the waters regularly intrude, but what occurs after human retreat becomes a reality, and take all reasonable measures to prevent toxins from seeping into the very same waters our heirs will depend upon for survival. In exchange for tax incentives, “abandonment certificates” should be required, based upon rigorous mandates. Existing pollution controls and laws need to be reviewed with SLR and tidal flooding in mind. Financial systems urgently need to help fund efforts to stop the flow of pollutants from our buildings. We must not assume that even LEED certified structures are ready for this challenge.

Legislatures need to focus on what the threat of non-carbon building emissions holds for the near future. Existing pollution control plans, regulations and laws need to be fortified by sound public policy requiring, as a condition precedent to property development, the built environment be made “ocean-safe,” to tough, state-of-the-art standards. The process of issuing demolition certificates must be more demanding. Intensified research of post-retreat acidification should immediately be funded.

Dangerous building materials and contaminants can be dealt with, but it is imperative that attention to this issue be given at the initial planning level…not just when properties are condemned in future years. Similarly, older structures must not be overlooked for their toxicity potential.

Some governments and owners have made a good start in understanding and appreciating the problem. The International Living Building Institute, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and even Google have identified “red list building materials” that should not be used in new construction. But such efforts are only for new construction or those undergoing renovation.

“Ocean Safe” buildings must be our legacy. The dangers of SLR go far beyond losing property and disrupting lives. Permitting irresponsible construction techniques and unorganized coastal retreat is not only myopic, it is a continuing crime against nature. The privilege of living in an urban waterfront in 2015 shoulders a burden: leave it ready for the populations of 2030 and beyond.

About the Writer:

PK Das

P.K. Das is popularly known as an Architect-Activist. With an extremely strong emphasis on participatory planning, he hopes to integrate architecture and democracy to bring about desired social changes in the country.

P.K. Das

Integrating the waterfronts

Developing open, sustainable and resilient urban waterfronts is paramount. Also, integration of waterfronts with cities’ hinterlands and their social and cultural fabric in order to overcome their segregation and exclusivity is important. Therefore, evolving an integrated ecological structure that would re-define urban landscapes is our key mission.

Being on the waterfronts and bathing in the sheer beauty and vast expanse of openness extending up to the horizon, in dense city landscapes, is truly liberating. But, increasing attempts to colonize these common assets for private and exclusive consumption is steadfastly eroding larger public interest and undermining ecological and environmental interests too—all this besides capturing the very experiences of this openness and natural beauty for few. Under such city conditions, the need for developing an intimate and intrinsic relationship between people, ecology and city building—broadly termed as ecology of cities—becomes enormously complicated. Also, it is hard to achieve this important relationship due to ruling socio-political interests that are governed by short-term financial interests of dominant groups.

Tragically, in most instances the assessment and measure of a city’s development and prosperity are based on the extent to which reproduction and turnover of capitals are achieved. While this may be necessary, it is deplorable to pursue the same in-spite of larger sections of people being marginalized from the benefits of development as well as the continuing destruction of finely balanced, interconnected ecological cycles. A balance between these two aspects—financial prosperity and economic growth; along with programs that rebuild, harness and promote interconnectivity of the vast environmental and ecological assets—is daunting, particularly for many of us who are demanding a paradigm shift in the imaginations of an integrated and inclusive ecology of cities.

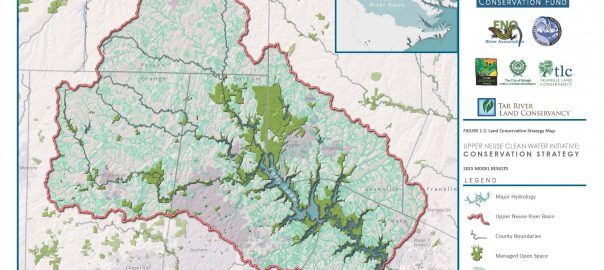

A fine example of such an effort in the achievement of a new ecology of cities imagination is the ‘Rebuild by Design‘ competition and its resulting projects that have been launched for implementation of waterfronts barriers in certain cities in the US by the Obama government. Even though the process does not sufficiently suggest ways of integrating the waterfronts with the city’s inner areas and neighborhoods, plans for building with nature are indeed commendable. The fact that these ideas can be furthered as models for planning cities and defining urban development is particularly noteworthy. It opens new avenues of thinking about physical planning of cities and conceptions about our built and natural environments.

These US examples are distinctly different from the hugely popular Barcelona-like waterfronts that are being pursued in many cities. The Barcelona waterfronts are places of high consumption and business turnover. This is a successful model of capturing natural areas for furthering market interest. Shopping malls, restaurants, cinema halls, aquariums etc. dominate the waterfronts, including building into the waters by landfilling. A few promenades are provided for leisure and walks in the backyards of these enormous building structures. The waterfronts are not realized from within the buildings that are contained spaces for transactions.

Real estate development as engines of capital reproduction and financial turnover has dominated city waterfronts across the world. As a result, vast stretches of vantage waterfronts have been developed as high cost private enclaves leaving out smaller less attractive parts for public access, as concessional spaces. Along with such developments, natural coastal conditions have been substantially destroyed, thus severing the ecological life cycles, including production and reproduction of flora, fauna and other aquatic life that thrive along these edges. That these natural conditions too stand as effective barriers against the vagaries of winds and floods were ignored in such instances. To conserve natural assets and protect the coastal edges is challenging as we squabble to capture them in the present urban development endeavors that are ridden with a build-more syndrome.

It is therefore important to not only rebuild with nature along coastal edges, but also develop streams of natural corridors across neighborhoods and cities in order to re-establish the symbiotic relationship between nature, people and habitation. These streams of corridors consisting of watercourses, forests of trees, wetlands, mudflats and others would inevitably be rich sites of intense participation and social engagement, thus nurturing and enriching community life and networks. Waterfronts cannot be sustained as isolated or segregated edges from rest of the city. They have to be considered as a thread of a larger ecological structure interwoven with other natural conditions, along with addressing various human needs in the city.

Waterfronts must also be realized and developed as a part of public open spaces plans and firmly placed in public realm. Active engagement of public on the waterfronts will ensure public vigilance and its protection from abuse and misuse. This will not only ensure the democratization of the waterfronts and public spaces, but also lead to the achievement of a sustainable and resilient ecology of cities. Waterfronts development is an opportunity and means for achieving these objectives.

About the Writer:

Ana Faggi

Ana Faggi graduated in agricultural engineering, and has a Ph.D. in Forest Science, she is currently Dean of the Engineer Faculty (Flores University, Argentina). Her main research interests are in Urban Ecology and Ecological Restoration.

Ana Faggi

Buenos Aires waterfront, where present management defeats ecology

Urban conglomerates like Buenos Aires and many neighbouring localities in the metropolitan area experience the reshaping of waterfronts as a catalyst for urban regeneration, which also is taking place in smaller Argentinean cities like Ushuaia, and some other inland riverine cities as Rosario, Paraná, and Neuquén.

The relationship between the Buenos Aires city and the estuary´s waterfront has been in the past very particular and conflicting. A common saying is “Buenos Aires grew turning its back to the river” which describes physically and metaphorically the historical relationship between city and riverside. The coast was developed into a harbour and a warehouse area for international maritime shipping and was predominantly inaccessible to the public. In 1918 a municipal resort gave direct access to the coast, and its beaches became very popular. But since 1960 the seaside´s appeal declined because swimming was forbidden due to water contamination. In the sixties, during the military government, the whole periphery of the shoreline was forbidden to the public.

Since the early 1980s, and especially with the country’s comeback of democratic life, the waterfront developed along two different paths. The renovation of the harbour docks followed a top-down process carried out by private-public enterprises. It was a successful and lucrative real-state transformation in which contemporary design and aesthetics had precedence. This was the origin of “Puerto Madero”, the youngest neighbourhood, most modern and expensive. Despite the fact that it is not affordable to live for the majority of the inhabitants the attractive public space is very used by all visitors.

On the other hand, the ecological restructuring of the riverfront was the outcome of a bottom-up process that involved many actors with conflicting interests arguing over three decades. Thanks to the NGO “Fundación Ciudad“, which enabled the involvement of otherwise excluded social groups and had ample community support behind its initiatives, the ecological rehabilitation of the coastal strip acquired relevancy and begun to be discussed. In my previous TNOC essay “Buenos Aires Tries to Design for Biodiversity” I reported on policies at the metropolitan scale proposing to rehabilitate biocorridors along watercourses. Unfortunately a different idea prevails: of designing a landscape with a clean and tidy style that does not match with what is natural. Up to now, little has been done for an ecological rehabilitation that puts priority on the local flora and fauna, restoring the living environment to sustainable conditions over time.

In February 2014, I went along the waterfront together with some colleagues, members of the Fundación Ciudad and people of the city council who are responsible to maintain and clean this area. The objective was to exchange ideas about sustainable management (such as with native venation in the figure below).

Unfortunately our recommendations to maintain natural areas were ignored by the council as you can see in in the image below—a photo taken at the same place just a week ago, in December 2014. A disproportionate cleaning effort goes to the management process rather than to maintain the riparian vegetation and its environmental benefits.

2015 will be the year of political change in Argentina, so a hot debate about candidate qualities already goes on. The current major of Buenos Aires gains more and more popularity through many infrastructure works during his administration. Recently, I heard on the radio an explanation of his high approval ratings: “most likely because he is an engineer, he carried out many works what was welcomed by many people”. But not without criticism: “his management has too much engineering but it lacks on humanity”.

Hearing this statement on the radio made me think about the removal of native scrublands along the waterfront. I wish that the New Year will bring Buenos Aires a better understanding of Nature !

About the Writer:

Andrew Grant

Andrew formed Grant Associates in 1997 to explore the emerging frontiers of landscape architecture within sustainable development. He has a fascination with creative ecology and the promotion of quality and innovation in landscape design. Each of his projects responds to the place, its inherent ecology and its people.

Andrew Grant

Urban Waterfronts are time machines—portals to other worlds past and present. On the one hand they are trading frontiers laced with nostalgia and countless human emotions and memories. On the other, they are a universal connection to our global environment and a litmus test of the health of the world. They have the potential to inspire a profound awareness of the connected world and as such they are important touchstones in urban planning.

We touch the waterfront—we touch the world

Given this pivotal link between city and planet we should be looking to mark developments in these locations with distinction and imagination. These are the places where human creative genius should be brought to bear in its most focused form. Urban Waterfronts must be beautiful, ecological and memorable.

Like it or not, commerce and the expectations of profit dictate the transformation of urban waterfronts. I suggest we can think of three ages of waterfront development reflecting the past, the present and the future.

1. The time of Industry and Commerce represents the past and tracks the explosion of waterfront developments on the back of global trade and shipping. Here the prime value was in the efficiency of storing and processing trading goods alongside the easiest moorings and best connected waterfronts. Interestingly, these industrial waterfronts typically demonstrate the value of practical multifunctionality in their planning and operation also represent an era of environmental degradation.

2. The time of Leisure and Commerce represents the present and implies the cleansing and opening up of former industrial waterfronts into desirable urban destinations. Here the value comes from the perceived added economic benefits of prime waterfront real estate. Multifunctional land use is more likely to be driven by the economics of commercial development rather than the optimised sustainable benefits of waterfront regeneration.

3. The time of Nature and Commerce is my anticipation of the future where waterfronts are transformed into resilient urban filter zones providing extensive habitats within and alongside high density beautiful developments. Here the value is in the diversity of function and the aesthetic, sensory and mitigating benefits of a healthy waterfront ecosystem. Multifunctionality is taken beyond simple economic returns or practical efficiencies into a whole different realm of social and ecological benefits. In addition to the enhanced real estate values are measurable economic benefits related to climate mitigation, biodiversity, resource management and the extraordinary forgotten value of immediate human contact with nature.

The way we treat these watery edge places reflects our contemporary values and throughout history these urban waterfronts have also marked human creativity and sense of adventure. They are unique in the urban environment and have the potential, perhaps more than any other space, to define the character and identity of cities.

The industrial period undoubtedly left a legacy of extraordinary development and environmental impact but what an exciting journey can be traced from the 17Th C in these waterfront locations. The infrastructure of global trade, exploration, innovation and the generation of the greatest cities in the world still resonates across the globe. Compare this to the current time of Leisure and Commerce that spawns extrusions of largely forgettable waterfront apartments, hotels, casinos, retail malls and offices all fed by chains of cafes, bars and restaurants. Will this period leave a similar legacy of distinguished human creativity and innovation?

Google ‘Waterfront Regeneration Projects’ (images) and you are overwhelmed by Masterplans and images portraying a green and happy future. Green corridors, waterfront bars and the occasional flight of seabirds populate the images in an almost universal display of the righteous nature of contemporary urban planning and design. But look carefully and it quickly becomes apparent that all we are looking at is a creeping globalisation using a banal and generic approach to the regeneration of these special places. Yes, they reflect a more public opening up of waterfronts and a reduction of environmental pollution but where are the surprises? Where are the creative waterfront landmarks of the 21st Century? Where are the unique responses to each geographical and ecological place? Where are the animals? Where is the wonder?

Similar research into Waterfront Conservation reveals entry after entry outlining the urgency and worthiness of a more ecologically sustainable approach to the restructuring of these post industrial environments but these rarely evoke any sense of the remarkable. Instead, they are bogged down with descriptions of mitigation, design guides, cultural and natural heritage and principles for regeneration. Worthy, important and necessary but, for me, Boring!

So how do we break out of this current planning cycle to reflect a more exciting, enlightened, and creative outlook? How do we move on to the time of Nature and Commerce? First and foremost I would place the words ‘imagination’ and ‘nature’ right at the heart of any visionary statement for waterfront regeneration. Four guiding themes could be:

— Dare to be different

— Celebrate the uniqueness of local ecology and habitats

— Deliver places with creativity, distinction and purpose that truly reflect our place in history

— Be guided by Imagination and Nature

But this begs the question: whose imagination? Who chooses and makes the decision to be bolder? What are the values that we want embodied in these future waterfront projects? In my opinion the vision and administrative process for demanding generous space for nature as well as permission to be imaginative should come from public authorities. If we are to create distinctive local waterfronts with a strong local identity we need more Governments and local authorities to have the confidence and vision to demand greater space for urban waterfront nature and to set the bar higher for imaginative and memorable designs.

In addition to setting the target we need to deliver the solutions. In my mind these more ambitious integrated objectives are dependent on a new type of collaboration in which the traditional hierarchy of professional disciplines and procurement systems are restructured. Different projects will require different team structures and relationships but each must place emphasis on creative and ecological leadership. For this reason landscape architecture is emerging as an important profession that can sit at the heart of waterfront regeneration projects. Sometimes leading, sometimes the creative and ecological conscience, sometimes providing specialist expertise in the specific design of elements.

Current projects around the world that illustrate the growing role of Landscape Architecture and the potential of distinctive, multifunctional and ecological landscapes include Barangaroo in Sydney. Here a major former industrial quarter is being redeveloped into a high value waterfront neighbourhood with extensive public space and regerated landscape. Peter Walker and Partners Barangaoroo Point Park powerfully symbolises the transformation of this industrial headland into a piece of reimagined nature right at the heart of this waterfront city. In the UK the Swansea Bay Tidal Lagoon will create a new waterfront for Swansea, a focus for water-based activities and a visitor destination in its own right. The masterplan, design coordination and public realm design for the project, by LDA Design, creates a ‘Maritime Park’ including new beaches, water sports, art and mariculture, between Swansea Bay’s beach to the west and Crymlyn Burrows natural dune system to the east.

At Grant Associates we have been fortunate to test these ideas on a number of important landscape projects. Gardens by the Bay in Singapore benefits from the overarching vision for Singapore as a ‘City in a Garden’ and an enlightened approach to integrated environmental infrastructure. Architecture, engineering, horticulture and ecology have merged as an integrated, living entity with its own unique and powerful 3D identity. This has allowed us to create a unique new waterfront Park that at one level has become an international symbol for the country and its ‘green’ agenda whilst offering a special and intimate encounter with plants and nature at the heart of this tropical metropolis.

Almost 20 years ago I, with Dr Mike Wells (also in this Roundtable), explored the seeds of this approach through the masterplan for Greenwich Peninsula in London and through the specific proposals for restructuring the river walls to allow the successful establishment of extensive intertidal habitats. This proved be an economically effective method of repairing the river wall, an ecologically beneficial intervention for the River Thames and a seasonally responsive spatial landscape that adds enormously to the visual setting of the waterfront.

Such multifunctional and inspiring waterfronts have to be our ambition. The time of Nature and Commerce has got to come—and quickly.

About the Writer:

John Hartig

Dr. John Hartig is a Visiting Scholar at the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research at the University of Windsor where he is undertaking interdisciplinary research on the cleanup, restoration, and revitalization of the most polluted areas of the Great Lakes.

John Hartig

Creating an urban waterfront porch for people and wildlife

Situated at the heart of the Laurentian Great Lakes is the Detroit River. The Detroit River is not a traditional river as most people understand it, but a 51.5-km connecting river system through which the entire upper Great Lakes (i.e., lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron) flow to the lower Great Lakes (i.e., lakes Erie and Ontario). It provides 80% of the water inflow to Lake Erie.

Detroit, Michigan and Windsor, Ontario are the automobile capitals of the United States and Canada, respectively, and make up a binational metropolitan area that includes nearly six million people. Its highly industrialized and urban landscape is also considered part of the “rust belt”. This “rust belt” image is no longer fully accurate as the region is becoming a leader in restoring urban shoreline habitat, creating waterfront greenways, building the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, and celebrating North America’s only river system to receive both American and Canadian Heritage Rivers.

What was once considered a “hard” shoreline is now becoming “soft”. In the past, as commerce and industry expanded in the region, 49.9 of the 51.5 km of the U.S. mainland of the Detroit River shoreline were hardened with concrete or steel (hard shoreline engineering), providing no habitat for fish or wildlife. This shoreline hardening contributed to a 97% loss of coastal wetland habitats along the Detroit River.

Today, communities and businesses see the benefit of turning the focus towards the river and creating waterfront porches for both wildlife and people. One good example is General Motors in Downtown Detroit that changed the front door of its Global World Headquarters, called the Renaissance Center, from looking inland to facing the Detroit River. General Motors created a five-story glass atrium, called the Wintergarden, along the 5.5-mile Detroit RiverWalk that now attracts over three million annual visitors and showcases many examples of habitat restoration. Another good example is the brownfield cleanup of former industrial property in Trenton, Michigan that now serves as the gateway to the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, complete with a Gold LEED-certified visitor center. This represented the first time anywhere in the world that the ecological buffer of a “wetland of international importance’ (i.e, Humbug Marsh) had been expanded into a former industrial brownfield. Both of these examples showcase soft shoreline engineering that uses ecological principles and practices to reduce erosion and achieve stability and safety of shorelines, while enhancing habitat, improving aesthetics, enhancing urban quality of life, increasing waterfront property values, and even saving money when compared to installing concrete breakwaters or steel sheet piling.

In total, 53 soft shoreline engineering projects have been completed in the Detroit River watershed since 2000. All provide “teachable moments” for the value and benefits of urban habitat restoration and enhancement. This re-engineering of shorelines is critical for rehabilitating habitat for fish and wildlife, and for helping change the face of the Detroit-Windsor metropolitan area.

Key lessons learned include:

— Involve habitat experts up front in the design phase of waterfront planning

— Establish broad-based goals with quantitative targets to measure project success

— Ensure sound multidisciplinary technical support throughout the project

— Start with demonstration projects and attract many partners to leverage resources

— Treat habitat modification projects as experiments that promote learning, where hypotheses are developed and tested using scientific rigor

— Involve citizen scientists, volunteers, and universities in monitoring, and obtain commitments for post-project monitoring up front in project planning

— Measure economic, social, and environmental benefits, and communicate successes

— Promote education and outreach, including public events that showcase results and communicate benefits.

It has been stated that a rose that grows surrounded by concrete and steel is more remarkable than one that grows in a horticulturist’s garden. If that is the case, then the Detroit River’s soft shoreline engineering sites should be celebrated, valued, cherished, and emulated because of the many benefits. Much like the effort to recreate front porches on houses in cities to encourage a sense of community, soft engineered shorelines along waterfronts in urban areas can help recreate gathering places for both wildlife and people.

If you are interested in learning more about this topic or about what is being done to bring conservation to the Detroit, Michigan and Windsor, Ontario metropolitan area, you may want to read the new book titled Bringing Conservation to Cities: Lessons from Building the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge.

About the Writer:

Roland Lewis

A lifetime New Yorker, Roland Lewis has worked in the field of community development since 1984, when he began as a program associate at the Trust for Public Land. In the spring of 2007, Roland took the helm of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance, a not-for-profit organization dedicated to making the New York and New Jersey harbor and waterways accessible, healthy, and vibrant.

Roland Lewis

Humans have long had a symbiotic relationship with the water that surrounds us—for commerce, transportation and recreation. It started with the birth of western civilization along the Euphrates and the Nile and continues today in New York, Singapore, Rotterdam and hundreds of other vibrant cities. While oceans, lakes and rivers have been the nexus of commerce and culture, waterfront cities have had and always will have to confront the threat of coastal flooding and heavy storms.

The Industrial Revolution brought massive change to our waterfronts, which became logical sites for efficient production and delivery of goods. But for some time, industrial facilities, and the resulting contaminants, made many waterfront areas inaccessible and unappealing. Now, as we look on the landscape of our postindustrial cities following a half-century of deindustrialization, we see massive change and opportunity, unlocking new potential for many waterfronts. How can we live with the water, instead of fight it, while also preserving the economic and social mix of waterfront uses?

Port cities are the front lines in the era of a warming planet, globalization and increasing inequality. Challenging conditions arising from climate change are inevitable—and we have to be ready. Here in New York, Superstorm Sandy proved a tough lesson. Whether you endured destructive flooding, or were stuck in gas lines for hours, or lived without power for weeks, we all learned our waterfront is a utility on which we depend. “Resiliency” has become a buzzword, but with rising sea levels, harsher storms and more floods, it must inform everything that is developed at the water’s edge. Just as we have begun to truly enjoy cleaner waterways, waterborne transportation, and beautiful new waterfront open spaces, we have to rethink edge design. The Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance’s (MWA) Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines (WEDG) program, a voluntary, incentive-based rating system launching this month, seeks to balance access, resiliency, and ecology. The program will be a set of best practices in waterfront design and a tool for public stakeholders as well as developers of parks, residential and commercial buildings, and maritime industrial uses.

The embattled working waterfront deserves particular attention. Ports and supporting maritime industries, such as tug and barge operations and ship repair, are important drivers of our regional economies. Our increasingly interconnected world relies now more than ever on shipping to deliver the goods and energy we consume: approximately 90% of all products travel over water. This has substantial environmental benefits as well, as goods shipped by water consume only a small fraction of the energy of those shipped by land or air. The port of New York and New Jersey supports over 280,000 jobs and $37 billion in economic activity. Indeed New York’s economic ascendancy is inextricably linked to the harbor and the growth of the shipping industry, and the working waterfront continues to be a source of good jobs and a critical part of a diversified economy.

Indeed the waterfront should be an asset and a resource for all, though its transformation threatens to bring irreversible change to coastal communities. With cleaner water, attractive parks and lovely esplanades, our waterfronts have become attractive places, and developers and the moneyed class for whom they build have taken notice. Traditional working class waterfront communities are being gentrified, threatening to fashion a “gold coast” by and for the wealthy. A row of massive condominiums at the water’s edge may provide short-term gains in tax revue, construction jobs or other amenities, but it is a Faustian bargain. While all of us must do more to dampen the larger societal forces exacerbating inequality, we must not cede important functions of government—including but not limited to providing usable open space and maintaining critical infrastructure—to private actors.

On the waterfront, the past is prologue. These cities built on waterborne commerce and under the threat of storms, still receive and send our goods and are vulnerable to violent weather. Intelligent design of our harbors to function as ports, to be resilient in the era of climate change and to provide equitable access and use for all is the critical task at hand.

We must get it right. Our future depends on it.

About the Writer:

Joe Lobko

Joe is an architect with a particular interest in urban design, adaptive reuse and the non-profit sector. In 2006, he joined DTAH as a partner and in the same year he received an urban leadership award from the Canadian Urban Institute and became a fellow of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada.

Joe Lobko

Toronto is a city and region that continues to experience the various impacts and pressures of substantial, sustained population growth. Toronto’s waterfront revitalization evolves in that regional context, delivering upon some aspects of its early promise to create of a series of great, connected public spaces across its breadth.

Stretching over an area of about 2000 acres (800 hectares), along the northwest shoreline of Lake Ontario, and including an inner and outer harbour adjacent to the exquisite jewel that is the Toronto Islands, this area has been under intense study, design, and redevelopment for a period of over four decades, though its many past transformations have been underway for a much longer period of time. Public access has improved substantially and environmental clean-up has been completed on many of the brownfield industrial sites now undergoing transformation.

Over the past decade this effort has been championed by Waterfront Toronto—the quasi-governmental agency formed by three levels of government, Federal, Provincial and Municipal—to conceive, manage and implement the process and shape of waterfront revitalization on their collective behalf.

Some themes come to the surface when reflecting on the statements and questions posed by TNOC for this forum, in the context of the Toronto Waterfront:

1. Importance of A Collective Vision. “Removing Barriers/Making Connections, Building a Network of Spectacular Waterfront Parks and Public Spaces, Promoting a Clean and Green Environment, Creating Dynamic and Diverse New Communities.” A key excerpt from the City of Toronto Official Plan, describing the essential aspects of Toronto’s waterfront vision – ambitious, broad, open to complexity, evolution and balance – a collective vision that while clear and strong in its essential aspects, aspires to have the “light touch – loose fit” capacity necessary to adjust to evolving circumstances.

2. Involvement and influence of committed community leadership. There has been a long history of community involvement in the revitalization of the city’s ravine/watershed systems that terminate at the waterfront, which has laid the groundwork for consistent community commitment and support for the evolving vision of waterfront revitalization, a critical element of its ongoing success and implementation.

3. Waterfronts include and are impacted by adjacent watersheds. Waterfronts can be part of a larger network of connected green spaces, and in the case of Toronto, this means ensuring better natural as well as physical infrastructure connectivity, particularly up into the distinct ravine systems that characterize so much of Toronto’s natural footprint. The re-naturalization of the Lower Don River is a good example in support of this effort.

4. Bureaucratic leadership and creativity. Waterfront Toronto has done an excellent job of facilitating public support for a vision and transforming existing procedures and processes traditionally resistant to change and innovation.

5. High percentage of public land ownership. The high proportion of public land ownership in the territory involved in Toronto’s revitalization has allowed the transformation to be controlled by contract, as well as policy and legislation, a major advantage in the typical private/public partnerships used to implement most of the new buildings and public spaces to be constructed.

6. Substantial upfront investment in public infrastructure including parks, natural systems, great public spaces and streets, flood protection, and utilities (including smart city technology), delivered before new buildings come along, as a means of generating good/better value from private investment.

7. An appreciation of history and the importance of multi-generational thinking. The implementation of these kinds of projects can unfold over decades, and relies upon the energy of multiple generations of champions and stewards, a critical aspect of successful, sustainable community development.

Toronto’s waterfront and inter-connected ravine and water spaces have become increasingly important within this rapidly growing city, providing a broad range of public space experiences and environments, critical to supporting livable cities.

About the Writer:

Robert Morris-Nunn

Robert Morris-Nunn, director of Circa Morris Nunn, Architects, is regarded as one of Tasmania's most successful architects, and has practiced in Tasmania for almost 40 years, taking a special interest in the social impact of architecture and collaborative design processes.

Robert Morris-Nunn

Hobart is the second oldest port in Australia, and one of the largest natural river estuaries in the country. From a high point in the mid 20th century, when Tasmania was the ‘Apple Isle’ and most of its farm produce was exported direct to the UK, the port’s activities have progressively declined to the point where it is now only the point of departure of Australia’s Antarctic vessels, and visited every summer by cruise liners, who appreciate they can dock right next to the CBD and visit a small city tucked directly under the picturesque Mount Wellington.

Hobart as a capital city is very small, with a population of about 200,000 residents, and needless to say, an equally tiny and fragile economy. Things in Tasmania generally get preserved by neglect or lack of money. It is almost a virtue.

My own architectural practice has played a key role over the last 10 years in the waterfront’s revival, being responsible for the recycling of the two major mid 20thC waterfront warehouses into multifunctional civic buildings, a much acclaimed restoration/recycling of seven Georgian and Victorian warehouses into a distinctive hotel which integrates old and new; and most recently, the creation of a 80m long four story high, 5000 ton floating pier in the tradition of the now-vanished waterfront finger piers that were demolished 20 to 30 years ago when concrete cancer made their continued upkeep untenable.

My personal view regarding rejuvenation of a waterfront is that if the historic fabric can be preserved and put to an effective new use, this is by far the best possible outcome. Quite often the old buildings were simple vernacular structures, but they were generally built by maritime engineers to answer practical needs in a straightforward manner. Their recycling is both more economical than building from scratch, and with care, a far more environmentally sustainable new structure is created.

Where demolition has occurred (such as the removal of all but one of the old finger piers), I always try to reinstate new structures that are contemporary but which still allude to the buildings that formerly graced the area, particularly where these structures had a strong visual correlation with each other, as was the case with the old finger wharves.

The new floating ferry pier is a case in point. By building a 4m deep floating concrete pontoon, considerable economies could be made over a traditional piled wharf in addition to creating a useful basement storey. More importantly, I feel that the overall building form (length / height / proportions) should reflect the scale and feel to the remainder of the urban waterfront fabric.

The cladding of the ferry pier is a lightweight polycarbonate ribs injected with insulating nanogel, creating a diaphanous skin, which visually compliments the significant environmentally sustainable engineering services within it—the pier floats on concrete and runs on water! The pier behaves like a boat, with the superstructure being kept as light as possible so that the structure’s centre of gravity is below the waterline. The structure also rises and falls with the tide, so it is anchored to the seabed with triangulated diagonal cables that change their angle of thrust with the changing tide heights.

As much as the form incorporates memories, it is also very important that the uses that the spaces within have a community dimension, if not ownership. In the case of the pier, one complete floor level is given over to a large local produce and product market, with two informal cafes in addition to an up-market bar. The boarding level can become a function space for up to 1500 people outside the times when it is used by passengers alighting from ferries.

These multifaceted uses will bring diverse activities and give vitality to the building / boat every day and night, throughout all seasons. We believe it will be a significant step in the transformation of the old port from an industrial area to an urban civic precinct. It marks the beginning of a new chapter in the life of Hobart’s port.

About the Writer:

Rob Pirani

Robert Pirani is the program director for the New York-New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program at the Hudson River Foundation. HEP is a collaboration of government, scientists and the civic sector that helps protect and restore the harbor’s waters and habitat.

Rob Pirani

Realizing the promise of urban waterfronts starts with understanding the shoreline as a public utility. As with other public utilities, such as electrical, transit or water services, a city’s waterfront is a critical infrastructure that provides for human settlement while (hopefully) sustaining the underlying ecosystem. Its complex nature and competing uses makes management difficult. Grappling with the politics of allocating this limited resource has been a staple of western governments since the public trust doctrine was expounded by Roman Emperor Justinian in the sixth century.

Hurricane Sandy not only eroded the shorelines of New York and New Jersey, but, as is generally true with disasters, also exposed the inadequacies of our current management system. Its wake left a sharp focus on strategies suited for this new era of climate change. This includes integrating uses and, as the Dutch say, living with water, to maximize the potential benefits of the waterfront. But stacking functions—expecting specific pieces of land to do many things like meshing ecological restoration and risk reduction—makes treating the waterfront as a public utility even more critical.

Let’s consider first the structure and many functions of urban waterfronts. Like any shoreline, these waterfronts are a permeable edge that mediates between water and land. There are interactions between upland and benthic ecologic communities. There are incredibly rich fluxes of nutrients and sediment brought by streams and tides. Unique and highly productive wetland communities adapted to changing hydrologic conditions. This ecology generates incredibly valuable services, from fish nurseries to sequestering “blue” carbon.

The transformative nature of the shoreline is also critical for human settlement. It is small wonder that cities grow up by the water. The urban waterfront is a place where commerce shifts modes of transport, especially important for heavy freight and global trade. For better or worse, water is a useful media for diluting human sewage and other waste products. People love the waterfront as a place to live and recreate. The sharp edge provides visual relief from dense urban fabric, and an unequaled sense of place.

But water seeks its own level. What is critical in the climate change era is that the waterfront is not a hard boundary, but a zone that shifts with time and topography. And whether it is due to the twice-daily tide, seasonal flooding and erosion, or the long(ish) now of sea level rise, the waterfront of today at 11am is not the waterfront of tomorrow. The dynamic aspect of the shoreline has always been a cornerstone of coastal zone management—generally in an effort to control that dynamism. Urban waterfronts owe their form to the bulkheads, piers, beaches, and other structures that bring a certain order (and of course economic value) to this shifting environment. But the uncertain risks posed by a changing climate have scrambled engineering, financial, social and political calculations.

Integrating all this functionality and variability at the project level is seen as one means of unscrambling these calculations and addressing this new ‘normal’. In particular, the promise of employing existing habitat and “nature-based features” as a means of reducing risks posed by coastal storms and sea level rise is tremendously exciting. Funded projects like Scape’s Living Breakwater proposal for the Rebuild by Design Competition or New York Rising’s proposal for Spring Creek offer innovative and integrated designs that can reshape our connections to the estuary while mitigating risks of storms and sea level rise. Not incidentally, the opportunity to leverage funding available from the Sandy Supplemental legislation and other sources offer the prospect of addressing long-standing conservation and restoration goals.

But there are many scientific, engineering and management challenges to integrating restoration and hazard mitigation. Our limited engineering experience, challenges in projecting co-benefits, and understandably cautious federal and state permitting system suggests an adaptive management approach. Such an approach must be built on better understanding of baseline conditions, on-going monitoring, and maintenance. One such effort has been led by the Hudson River Estuary Program and the New York City Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency and Department of City Planning. The Hudson River Foundation’s recent call for proposals will also help address these questions.

But making such best practices real also requires considerations of funding strategies that reinforce long term performance and asset management. Other public utilities, such as transportation, water, and energy, rely on financing models that capture the value they create or the costs they have avoided. By building our understanding and documenting the long term ecosystem services of living shorelines, these techniques can be employed for financing the restoration of our waterfronts in a more resilient and productive way.

About the Writer:

Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk

Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk is an architect, urban designer and planner. She is co-author of Suburban Nation: the Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream, and The New Civic Art, and has had a career-long affiliation with the Univ. of Miami School of Architecture.

Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk

The Waterfront

The other day, during a stroll along the Baywalk in downtown Miami, I saw my first manatee. Considered endangered, the manatee is a large marine mammal endemic to the coastal tropics. My sister and I had just emerged from the porch of the new art museum, overlooking the waterfront rescued from industry, now a park.

Standing on the seawall, we were looking across the bay at Miami Beach, the destination of dreams, a skyline squiggle above the water’s surface. Closer, cruise ships lined up at the port like skyscrapers lying on their sides, prepared to visit the exotic Surrounding us were tall buildings assembled at the edge of the land, representing businesses and residents from throughout the hemisphere.

Standing on the seawall, we were looking across the bay at Miami Beach, the destination of dreams, a skyline squiggle above the water’s surface. Closer, cruise ships lined up at the port like skyscrapers lying on their sides, prepared to visit the exotic Surrounding us were tall buildings assembled at the edge of the land, representing businesses and residents from throughout the hemisphere.

This scan of the waterscape and the land, the panorama before us, was interrupted by the motion at our feet. The large sea creature lumbered gracefully near the sea wall, puffing spray at surfacings, mindful of our presence, maintaining a pace toward her destination. We watched her slick thick body undulate through the shallow still clear water—imagining her world, and places and creatures far away – until the distance concealed her.

About the Writer:

Andréa Albuquerque G. Redondo

Andréa Albuquerque G. Redondo is an architect devoted to the study and analysis of building codes and urban laws especially related to Rio de Janeiro, and its consequences for the City development.

Andréa Albuquerque G. Redondo

O RIO DE JANEIRO À BEIRA D’ÁGUA

Rio de Janeiro was founded 450 ago, grew around Guanabara Bay and several hills, and spread into North and West directions towards inland. From the 19th Century on it headed South along the coast. Our ‘East’ is the sea. Natural and urban environment in Rio exist together.

The waterfront is heavily populated. In the northern part of the bay port and industrial activities once closed down created abandoned areas, as occurred in many cities. In the front shore neighborhoods, habitation, commerce and services sector are mixed, except at the front land, destined to be apartments, hotels and restaurants by the land-use policy.

Unfortunately water pollution is a problem. Cleaning the marvelous Bay is always postponed, beaches are polluted, lagoons and streams are silt. The absence of sanitation in some vicinities and inefficient controls even in official sections brings bad results from an ecological standpoint. Fortunately, Brazilian Law prohibits exclusive access to the shore, as beachfronts are federal property, except in military areas. It is said that beaches are considered the most democratic space in Rio!

Irregular constructions, or ‘favelas’, exist all over the city. The consolidated ones are popular neighborhoods. Housing policy in early 60’s and 70’s removed some from the acquisitive South area, and transferred residents to distant projects. Those at Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon were replaced by very high value buildings. In North and West regions favelas still go around lagoons, canals and streams.

Recover the degraded environment or urban land vs. social issues is a complex task. Sometimes radical actions are required to defend either (1) ecology or (2) people. In the first case is necessary to prevent predatory urban occupation—formal or not—“rescue” invaded shorelines, and free ecological protected areas, even if families must be transferred according to the 1990’s Housing Policy. Second, if removal of constructions is impossible due to its consolidation and extension, adequate planning may reduce harm and with ecological benefits for all.

In both conditions land value grows. Avoiding gentrification process caused by “market laws” is a challenge, especially in Rio where pressure from real estate business is strong and permanent. It’s a public sector duty (1) in areas where construction is proper, to stimulate multipurpose structure for habitation, commerce and services, provide public spaces; and (2) in protected areas search private sector support to sustain it or assume the necessary budget.

Successful stories depend on the way we look. At Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, Rio’s post-card, there was a trade-off. For landscape, tourism, investors and new residents, it’s a success story. However, new projects create new places of poverty, with lack of infrastructure, to which poor people, losing their original homes, are moved. The transference model has been destructive and inappropriate.

Successful stories depend on the way we look. At Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, Rio’s post-card, there was a trade-off. For landscape, tourism, investors and new residents, it’s a success story. However, new projects create new places of poverty, with lack of infrastructure, to which poor people, losing their original homes, are moved. The transference model has been destructive and inappropriate.

The Port Region renovation is still unpredictable. Planning was conducted by financial interests and allows the construction of 30-50 floor towers. This area received huge and expensive infrastructure and has attracted only entrepreneurs and investors for commercial buildings construction. Without permanent residents it will be another lifeless place.

Protection for natural and urban environments must be appropriate and guide city planning whenever necessary for ecological purposes, independently of the land’s economic value, though balance is required.

Respect for environmental questions should be imposed by building codes and law enforcement. However, in the name of the 2016 Olympics, occupation has increased in free areas, flood-risky grounds and fragile hillsides, propelled by questionable new urban ratios for higher and bigger buildings and hotels, plus fiscal incentives. Pressure for real estate private enterprises along shorelines (and everywhere!) has had governmental support. Recent examples are a luxurious hotel and condo, and the polemical Olympic Golf Course built in Marapendi Reserve, both in protected areas, and worse, the course eliminates an ecological park, and suppressed potential avenues of dissent, despite lively defenders, urban planners and lawyers protests.

200 years ago Rio turning back to the water; sea bathing was a medication. 100 years ago demolished historic hills gave place to densely occupied flat ground and provided landfill over waters; stone mountains were raw material for construction, pavement and wharfs. There were positive actions in past, too: in the Imperial 19th Century Tijuca Forest, devastated by coffee crops, was replanted; in the 20th Century the municipality prohibited stone extraction; Culture and Environment Preservation policies were reinforced. Avoiding regression is imperative.

Without its Nature Rio would not be an Historic Urban Landscape. Even in our difficult current situation, Rio de Janeiro is still the Wonderful City!

About the Writer:

Bradley Rink

Bradley Rink is a human geographer focusing on mobilities, tourism and place-making. His interests lie in the relational aspects of people, objects and ideas in the urban environment.

Bradley Rink

The urban waterfront: quartering nature and the city

Cities are necessarily heterogeneous and multiple: they are sites where we encounter difference and where humanity and nature come crashing up against each other. Cities both embrace and abrade nature in the same turn. Urban waterfronts are no different in that they serve as the point of contact between the ‘wilderness’ of the open sea or river and the city that lines its shore. Waterfront developments have an opportunity to reconnect cities to their marine or riverine ecologies, but also run the risk of being neither ecologically sound nor socially inclusive. They may become ‘quartered’ urban spaces just like so many others that turn their backs to the cities where they are situated, or they may become the centrepiece of the city itself, engaged as a powerful tool to attract citizens and visitors to the aquatic urban edge.

An example of one such development is Cape Town’s Victoria & Alfred Waterfront. Since the late 1980s the former docklands district comprised of a jumble of warehouses, jetties and a power station has been transformed into what was promised to be an ‘African Riviera’ (Ferreira & Visser 2007), serving to elevate the status of the urban waterfront not simply for the city but for an entire continent. The V&A Waterfront is very much an urban quarter that presents the waters’ edge as a distinct cultural landscape: a spectacle that is steps away from the ambient urbanities that surround it, but discursively differentiated as a seaside entertainment world. In the V&A Waterfront we find a space that is the locus for the symbolic framing of culture, to use Bell & Jayne’s (2004) definition, a space that offers possibilities for identity production and consumption, and a space that enables commodification of the urban experience with little reference to its maritime origins other than the name and location itself.

In spite of this, the imaginary of the V&A Waterfront is one that acts to reconnect the city of Cape Town and its maritime past with a distinctly modern, consumer future. It is a place that makes a nod to the Cape Town’s connection to the sea while it also invites its patrons to indulge in the pleasures of upmarket shopping, dining and entertainment. If you have a yacht or if you arrive on a cruise liner, then your connection from sea to city is complete, but for everyone else, it is a mall just like so many other (Houssay-Holzschuch & Teppo 2009).

The V&A Waterfront has no doubt been a success in many ways: it has created new jobs; it continues to attract tourists and their spending; it serves as a site of mixing in spite of the exclusivity of its consumer-driven purpose. However, its success in connecting urban dwellers and nature has yet to be proven. The spectacle produced by developments of its kind is less about a connection between city and sea than it is about creating a shopper’s paradise.

This type of waterfront development is driven not by concerns over the relationship between city and sea as it is about the re-purposing of otherwise disused waterfront warehouses that proved to be a white elephant on Africa’s Riviera.

References:

Bell, David and Jayne, Mark. 2004. Conceptualizing the City of Quarters, In Bell, David and Jayne, Mark (eds) City of Quarters: Urban villages in the contemporary city. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1-12.

Ferreira, Sanette, & Gustav Visser. 2007. Creating an African Riviera: Revisiting the Impact of the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront Development in Cape Town. Urban Forum. 18 (3): 227-246.

Houssay-Holzschuch, Myriam, & Annika Teppo. 2009. A mall for all? Race and public space in post-apartheid Cape Town. Cultural Geographies. 16 (3): 351-379.

About the Writer:

Hita Unnikrishnan

A Newton International Fellow at the Urban Institute, The University of Sheffield, Hita studies histories of lost urban commons among the networked lakes of Bengaluru, India.

Hita Unnikrishnan

Rethinking urban waterfronts in India—a perspective from Bengaluru

India is a rapidly urbanizing country with vibrant historical and cultural diversity spanning centuries. Given its formerly rural character, most of this relates to how people identify with their water resources—oceans, rivers, or lakes. Changes driven by rapid urbanization have meant that lakes and other water bodies have acquired different and often dynamic meanings over time.

One example is the South Indian city of Bengaluru (where I hail from), famous for being the software capital of the country. Also known as the Garden City, Bengaluru by this name, has a relatively unknown history dating back to at least 890 AD (when the first record of the word ‘Bengaluru’ appears). To overcome its natural propensity for drought, low lying areas were used to create large reservoirs (tanks) that supported the city for many a century. When the city started importing its water from the Cauvery, a river thousands of miles away, these tanks lost prominence and became vulnerable. Today known as lakes, they represent urban waterfronts that are both ecologically and socially important.

My work revolves around historical and contemporary dependencies of people on these waterbodies, set within changes in their governance and management. We explored the historical trajectory of a centrally placed lake—the Sampangi Lake, which eventually became a sports stadium in the heart of the city. Built around the time the city was founded in the second half of the sixteenth century, this lake was important both economically and culturally. In fact, this lake is one of the venues for the oldest festival in the city—the Karaga that reveres the sacredness of water. Sadly, today only a small rectangular tank built for this cultural purpose reminds the casual passer-by of this once majestic lake surrounded by horticultural farms and attendant hamlets.

Colonial Bengaluru was divided into two zones—the exclusively British Cantonment and the Pete managed by the Wodeyars of Mysuru. This lake, in the Pete, still provided water to the Cantonment until the Cauvery scheme of water supply became operational. There were many disputes at this time, all centred upon different uses of the lake and which use was considered more important. Uses such as water for horticulture warred with those of water supply to the cantonment. These were in further conflict with recreational needs of the population, as surroundings of the lake were fertile turf for a polo playing population. Into this melee were thrown in aesthetic representations—that of it being a beautiful landscape upon which to gaze from the window of a nearby bungalow without fear of inundation by its stormy waters. What eventually triumphed were those ideas of urban waterfronts that held most political leverage—those of aesthetics and recreation—ideas that resonate even today in the conversion of the lake into a state of the art sports stadium. The memory of a water body supporting other uses lives on only in memories of older residents who have switched professions following the lake’s decline.

History repeats itself in contemporary conceptualizations of the lake. Today the lake is seen as a space that supports a great diversity of plants, avifauna and insects. It is perceived to be a lung space for urban middle and high income groups who live in gated communities close to the waterfront. It is also seen as an ideal location for recreational activities such as water sports, jogging or angling. It is a place where young lovers rest their heads on each other’s shoulders and enjoy the time they have together.

What it is not perceived as is a water resource for urban agriculturists or a sacred space for communities. It is not seen as a space supporting a fisherman casting his net, a washerman beating the dirt out of clothes, a pastoralist grazing his cattle or cutting fodder. Yet, the lake is bustling with these activities, its waters mute witness to trials of the people accessing it.

Contemporary policies like privatization also prioritize recreation, aesthetics and real estate over other uses of lakes and exclude both ecology and other social needs. This creates a regime of exclusion, enforced through entry charges or aesthetics. Exclusion can also happen when only the ecology of the lake is prioritized. In such cases also, it is the traditional livelihood group who suffer the most. Oftentimes, people have to switch occupations and carve out a new lifestyle completely alien to all they have known. All of this only reduces the value of these resources in the eyes of a substantial population, who, while possessing little political leverage, represent a large number of lake dependents.

We therefore need to look into what the past can teach us about heterogeneities that characterize an urban waterfront. To think beyond commercial, aesthetic and recreational interests, for a lake that is all of these, yet indispensable to traditional and other livelihood groups. To look at how one can balance the social and the natural. A new way of thinking is what is needed—that of perceiving the lake as a social-ecological system,where the natural and the social balance each other and drive the system forward. Only then, can we think of waterfront development policies or practices that are both ecologically sound and socially equitable.

About the Writer:

Jay Valgora

Mr. Valgora brings together an extraordinary range of disciplines at all scales: architecture, waterfront master planning, urban design, and interiors. He founded STUDIO V to create work that is connected to function, history and context.

Jay Valgora

NEW YORK’S EAST RIVER: A new Central Park for the 21st Century

“The city seen from the Queensboro Bridge is always the city seen for the first time, in its first wild promise of all the mystery and the beauty in the world.”

“I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes—a fresh, green breast of the new world . . . for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

To chase a romanticized perspective for the urban waterfront is to neglect the reality that the great green breast of Manhattan is gone. The ‘wild promise’ however, is not.

A vision for the new urban waterfront requires rhetorical ammunition as much as political will, the support of the community as much as allocation of money. A vision for the waterfront requires an integration of opposites to address the 21st century culture of the metropolis: center and edge, public space and private enterprise, green space and urban form, sustainability and development, the agora and the acropolis.

In the early 21st century two nearly simultaneous events occurred that set the stage for the urban waterfront: the heavily industrialized waterfronts of western cities fell into disuse through massive change in the global economy, and the tipping point occurred where the majority of people now live in urban areas. This simultaneous occurrence offers urban waterfronts a new possibility of the wild promise glimpsed by Fitzgerald.

New York City offers precedent and opportunity for a new rhetoric to reinvent the urban waterfront. Of the five boroughs that comprise New York City, four are islands and one is a peninsula, arrayed around one of the greatest natural harbors in the world. The urban waterfront has always provided transportation, economic vitality, natural limits to encourage urban density, and resources that evolved over time: food, commerce, industry, and recreation. The NYC waterfront comprises every condition: esplanades, nature preserves, wetlands, parks, marinas, industrial sites, beaches, ruins, and canals.

But New York has always been a laboratory for experimental design and urban density. A brief perusal of some of the radical experiments of New York’s urban past can point the way for a new rhetoric for the urban waterfront.

19th CENTURY: CENTRAL PARK was a pioneering effort in large-scale creation of urban public space, the manufacturing of green area intended to mimic the original green breast of Manhattan and restore it to the heart of the urban condition. Olmsted created a new center around which the dense urban mass would grow. His was an experiment in artificial landscapes, carving centers against non-existent edges, overlapping systems of transportation, and radical social integration.

20th CENTURY: THE WEST SIDE began with Olmsted’s partially realized Riverside Park but hit its stride in the 20th century with Robert Moses’ parkway expansion (1930s) and the Hudson River Park (early 2000s). Progressing from its original romanticized extension of the Hudson River Valley to the adoption of industry, the abolition of the abattoirs, a paean to the automobile, and ending with a linear park linking piers, greenery, and bicycles the West Side exemplifies the progressive design ideologies of the 20th century, both successful and less so.

21st CENTURY: THE EAST RIVER has historically been the edge of New York City: the division between city and country, metropolis and suburb. This edge provided Fitzgerald’s point of view outside to overlook “the city”. Today, the East River offers a very different potential: to become the center. It will no longer be a moat or wall dividing boroughs. The riverfront can provide a diverse and mutable network of public spaces, parks, development sites, sustainable communities, new institutions, and transportation infrastructure.

The East River provides the ineluctable opportunity to create a new Central Park of the 21st century. Do we dare to build a new Central Park today? Where do we find space and resources? The future of New York City is not Manhattan. The future is Astoria, Long Island City, Greenpoint, DUMBO, Sunset Park, Gravesend, the shores of Staten Island and the waterways of the Bronx.

Olmsted allotted boundaries (defining Space) and Moses worked against them (developing Edges), but the 21stC embraces integration, combining edge and center, transparency and density, combining public space, buildings and water (a true Network). By transforming the edges on both sides of the river, re-defining open spaces, and designing a fluid infrastructure network with water taxis, bus rapid transit, light rail and connective open space we can create the next great center for New York and a model for urban waterfronts around the world: providing new mixed use neighborhoods, housing, parks, schools, and public institutions, while increasing resiliency, ecological, economic, and social goals.

The great historic plans of New York can serve as benchmarks for the creation of powerful public spaces, but also serve as a foundation to build a 21stC rhetoric for the design of the waterfront. So we can embrace the city from below the Queensboro Bridge, as much as we do from atop it.

About the Writer:

Mike Wells

Dr Mike Wells FCIEEM is a published ecological consultant ecologist, ecourbanist and green infrastructure specialist with a global outlook and portfolio of projects.

Mike Wells

By abusing water edge environments through development and pollution we are in many ways killing and unbalancing ourselves. Our evolutionary ancestors came from the sea. We have gills as babies in the womb. Our blood plasma is isotonic with seawater. We are almost 60% water and need fresh clean water almost daily to survive. The now well-substantiated theory of biophilia holds that over the relatively short evolutionary history of Homo sapiens we have remained instinctively drawn to environments that provide what we need, especially at the interface between land and water where there is an abundance of life. When we abuse or degrade aquatic and marginal environments we are going against the grain of our deepest instincts in a way that damages our psychologically wellbeing and can threaten our lives.

Accordingly we should think less of there needing to be being tradeoffs between ecology on the one hand, and environment and social fabric on the other. We should instead think of designing for new synergies, with planning decisions based on new accounting methods that include the value of ecosystem services and the avoidance of long-term costs through increasing environmental resilience.

The great psychological wellbeing engendered by healthy aquatic fringe biotopes is just one example of the extremely important ecosystem services these habitats provide. The frequent destruction and degradation of the delicate intertidal and inshore sub-tidal communities of saltmarsh/mangrove, seagrass and coral reefs has meant huge harm to fish nurseries and coastal and sea fisheries. It has also increased our vulnerability to hurricanes, typhoons and tsunamis at a time of significant anthropogenic climate change and sea level rise.

The town of Tacloban in the Philippines was destroyed by super-typhoon Haiyan in 2013. The Comprehensive Rehabilitation and Recovery Plan published in October 2014 includes for the relocation of over 200,000 people away from the coast and restoration of coastal ecosystems as defences. In the more urban areas of Tacloban, however, faith appears still to be being placed (I believe unwisely) in ‘holding the line’ with new corniches and levies rather than in managed retreat and restoration of coastal habitats.

In the USA, New Orleans has been proudly rebuilding and restoring levies, but the key debate remains how to reverse the loss of coastal wetlands between sea and city which are capable when of absorbing much of the force of hurricanes. This entails catchment-scale management planning, removal of hard physical intrusions and walls around rivers and reconnecting rivers with their floodplains.

In Iskandar Malaysia along the straits of Johor the loss of mangrove fringe habitat and hinterland forest has been relentless. Instead, such coastal development could and should be tucked behind substantial mangrove fringes, leaving enough space for inland migration of fringe habitats under sea level rise.

In Penang I recently advised the Malaysian government on the factors holding back the development of the State economy. My conclusion was that top talent will increasingly choose to avoid places where the rivers, seas and beaches are poisoned and the environment is generally poorly prioritised. Reversing the damage is something I termed ‘The Penang Project’—an environmental restoration to allow Penang to claim first world ‘liveability’.

No matter how formal and pre-developed a water-edge habitat is, there is always something that can and should be done to restore, respect and enhance the vital ecosystems that thrive, or once thrived, there. In the late 1990s, I led the ecological regeneration of the Greenwich Peninsula in London, UK. This work included incorporating a saltmarsh terrace into a new river wall on a ledge as little as 7m wide. This terrace has now become one of the most important Sea Bass nurseries in the southeast of England. The initiative was strongly driven by the UK Environment Agency who became a development partner. The UK government, I think unwisely, has now reduced funding to strong environmental agencies such as this and forced a disbanding of expertise that had taken decades to build up, based on the false premise that the environmental factors pose a barrier to economic development.

In summary, I maintain that there should never be a development near water where the ecological wellbeing of our water edge environments is not protected, restored and enhanced, no matter how high the commercial values that apply. Smart waterfront development invests in ecosystems and is not contingent upon their destruction. To do this we need to strengthen the government funded agencies that have the expertise to work with the private sector to deliver urban waterside green infrastructure and ecosystem services in every type of development project. We also need inclusive accounting of ecosystem services lost or restored in such projects to make decisions that will stand the test of time.

Superb !! great job

Very Good initiative

I will be attempt to it

An undercurrent to many of these responses is who gets to choose what the waterfronts will be. For example, Andrew Grant says “…But this begs the question: whose imagination? Who chooses and makes the decision to be bolder? What are the values that we want embodied in these future waterfront projects? In my opinion the vision and administrative process for demanding generous space for nature as well as permission to be imaginative should come from public authorities.”

To this I would add the nuance: public authorities acting on the desires and best interests of the public.