Measures taken in cities to improve their adaptation to drought and for carbon sequestration are usually based on general standards to reduce water consumption and greenhouse gas emissions and/or to reach an efficient use of water and energy. Normally, these proposals are introduced using ‘globalized’ technologies, which are applied everywhere regardless of context.

But nature and rural areas near cities can provide key ideas to address these issues which are more in line with local needs and nature. An example can be found in the Elqui Valley in the north of Chile, where the carrying capacity for human life has been exceeded. Here, the semiarid climate conditions, increased intensity by the lack of water, land use change (from forest to urban land) and by climate change effects, create a very harsh environment in which to live. However, this has triggered in local people a capacity for innovation to survive in an extreme dry environment. Local knowledge and methods have been used to make efficient use of water and of the land, to grow food, fix CO2 and to develop an environment with good quality of life.

These coping strategies have influenced the shape, materiality, space and way of life in the Valley, which in turn suggest innovative ideas that can be used to inform urban planning and design. These four aspects can be seen as adaptive resources that can contribute to urban resilience to drought and carbon sequestration in multiple dimensions.

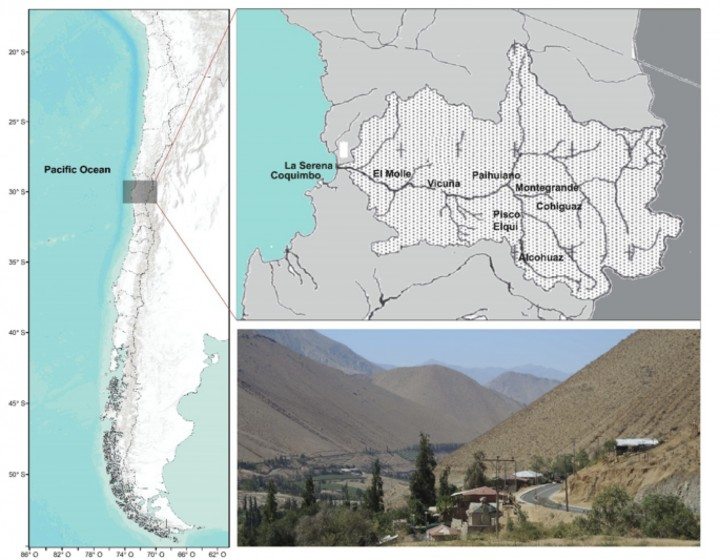

The Elqui Valley is located in a watershed, in the Region of Coquimbo, in northern Chile. The main river of this basin is the Elqui, which arises from the confluence of the Claro and Turbio rivers, coming both from the Andes. The Elqui River extends into the Pacific Ocean, a few kilometers north of the emerging metropolitan area of La Serena – Coquimbo, located on the coast. The Valley, comprising 150 km between hills planted with vineyards, is inhabited by villagers that for years have combined agriculture with astronomic tourism (a type of special interest tourism focused on visiting astronomic observatories to enjoy and learn about the solar system) for survival. Long periods of sunshine throughout the year and a clear sky favor both activities. However, population growth has been significant in recent decades, adding many who seek a closer contact with nature and relief from stressful city life, causing an imbalance with respect to the resources which are spent and consumed, mainly water. The reservoirs, located in the Valley, provide water for the 365.371 inhabitants of the Elqui Province, where the Valley is located, including 302.131 people living in the Metropolitan Area mentioned above.

In short, water demand now exceeds the carrying capacity. The population that can be supported indefinitely by ecosystems in the Valley, without destroying it, has been altered. This situation has been previously observed in other contexts as in the Nile River Valley, where population growth, coupled with ease of exports of goods and globalization, altered the natural dynamics of the territory. Adaptive measures in this case included increasing dam numbers on the river, water control for favoring a bi-annual irrigation regime, and the incorporation of artificial fertilizers, which has caused significant changes in the local ecology. In the Elqui Valley more subtle and less invasive solutions can be observed, developed by the local inhabitants, which could be extrapolated to the development of nearby urban environments, especially in the context of emerging cities that occupy natural resources such as water for its operation.

Shape, materiality and urban aesthetic

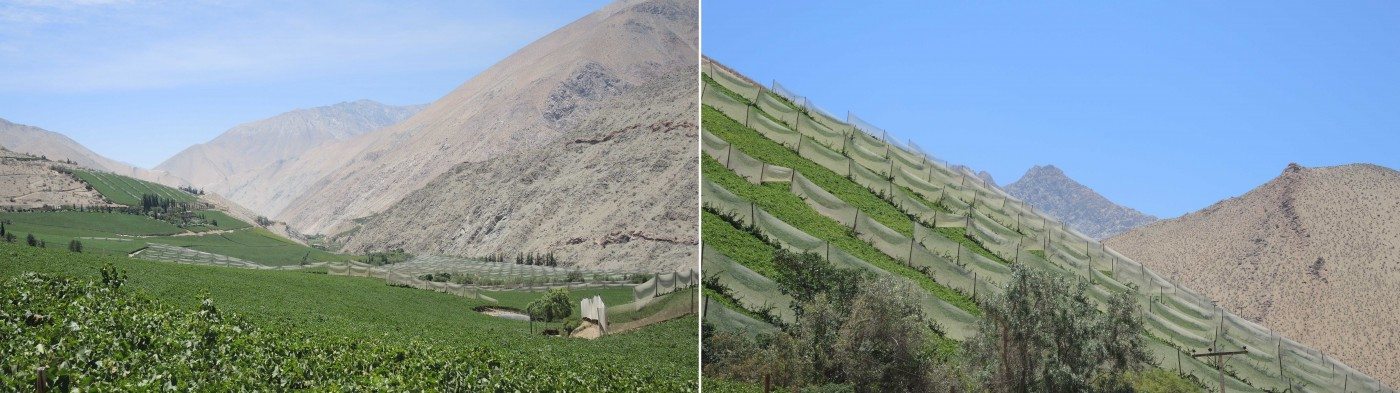

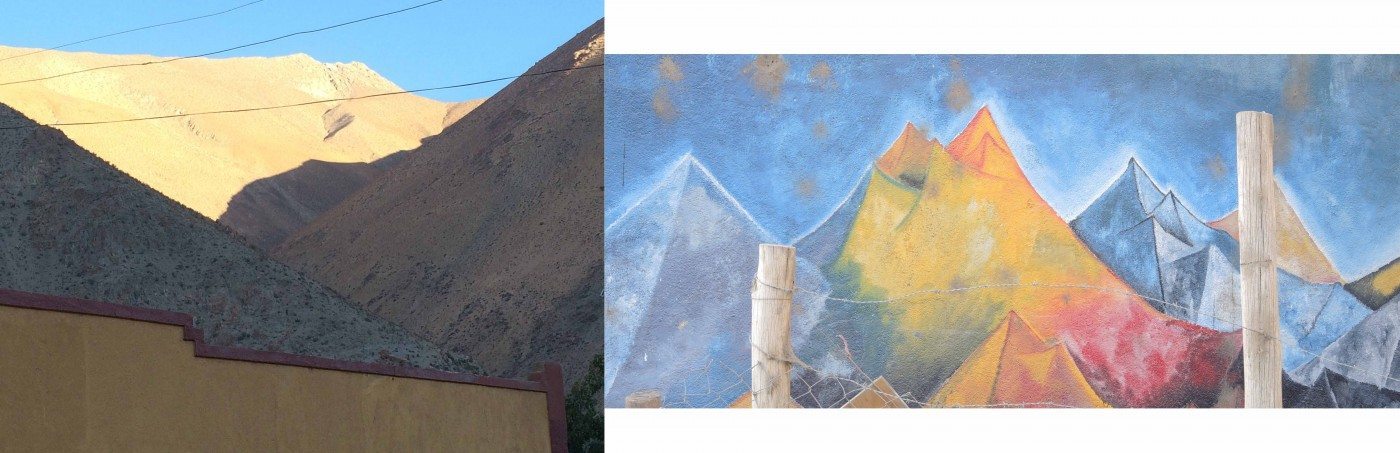

The mountain formations in the Valley show a clear triangular shape; they are very high and dissected by fluvial erosion. In the high mountain area, heights reach and surpass the 5000 meters above sea level, with steep slopes (15.1-25 °), although 41% of the basin have moderate slopes (5.1-15 °). These conditions have been ‘dominated’ by the local inhabitants for the development of agriculture in slope and in a triangular manner. In this territory, traditional terraced farming practices have been adapted to local geography to make better use of water, including a system of ‘mesh traps fog’. Usually, a dense fog known as ‘camanchaca’ gets concentrated in coastal mountains; this can be described as a stream of cold air which gets condensed due to the intense evaporation. This dense fog is accumulated and reused for irrigation. At the same time, the white color of the mesh, and the green of the crops, generates a rather provocative contrast to the brown and gray colored hills, characterizing a unique landscape of great beauty that favors survival and supports tourism.

This form of land use, in harmony with the surrounding landscape, should be of great interest to urban planners when deciding how coastal cities of this valley might expand and densify. For example, in areas of slopes, urban densities can be reduced to make way for urban agriculture and access to the coastal fog; this can be collected by urban residents themselves and used to irrigate their gardens, among other uses. At the same time, urban citizens would have an active involvement in the shape of urban landscapes with a particular aesthetic, connecting their urban life with natural dynamics, providing identity to the consolidation of metropolitan areas, which tend to the globalization of its landscape due to the great influence of the real estate and international markets.

Use of space and urban growth

To mitigate CO2 released by the human activities in the valley, recent studies indicate that the development of the basin should consider at least 61 hectares of forest vegetation per hectare of housing; or, the average housing density should not exceed 3.20 inhabitants / ha. This means a single dwelling per hectare of forest, or a 53 apartment buildings on 60 ha of land.

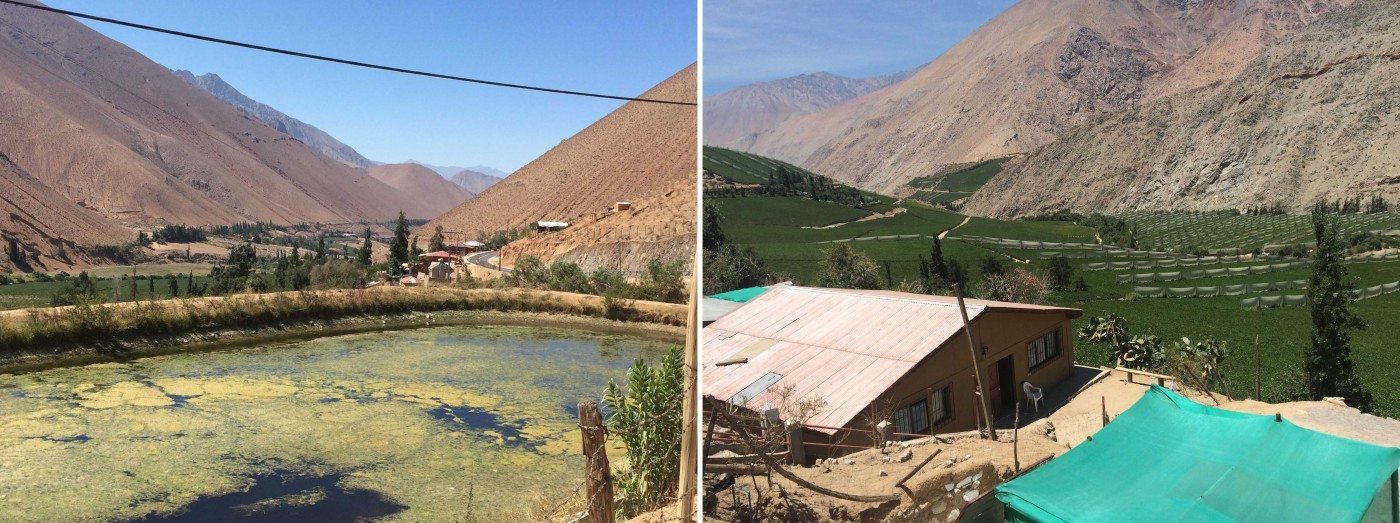

In the inner parts of the valley however, a good balance of built and forest areas is observed probably due to concentration of the population in the oasis. In these places, the vegetation and water provide moderate temperatures and shade, much desired in these latitudes. In this sector of the valley, fragmented and scattered occupation of the territory is observed for the development of human life, which is conditioned by the river matrix. This is similar to how land use was distributed in ancient times. For example, in the Nile River, mentioned above, the limit between agricultural and urban land was established based on the area flooded by the river. This would allow irrigation as well as fertilization of agricultural land. Housing areas instead, were allocated after that, on higher ground. This is actually a land use approach that is far from the manner in which big cities develop. Nowadays, land use and urban sprawl is mostly influenced by economic pressures. A denser land use means more space for housing, commerce and industrial facilities, and the possibility this type of urban planning would deteriorate natural systems is non-influential most of the time.

It is well known that within the urban environment, the existing plant material in parks, avenues, green roofs and gardens could help in the process of fixing CO2. However, for true impact, urban design should be guided by a study of the carrying capacity of the local territory, which rarely occurs prior to planning. For example, this type of studies can inform the percentage of minimum green areas required in the development of new suburbs, a measure which is usually specified in local planning regulations. This type of studies also can inform about the plants which have a higher carbon sequestration capacity, which in the valley include various trees and fruit plant species, that can be recommended in land use planning and introduced in urban parks.

With such an approach, urban and regional planning can be enhanced by specific results to define urban densities and land uses, which contribute to the adaptation of cities to the natural environment, which ultimately, is what sustains them. Thus, urban development can be linked with the ecological support, to for example, control CO2 emissions. At the same time, urban form can take a local character, contributing to urban landscape identity and local conservation practices of the natural and rural environment.

Rural way of life and urban wellbeing

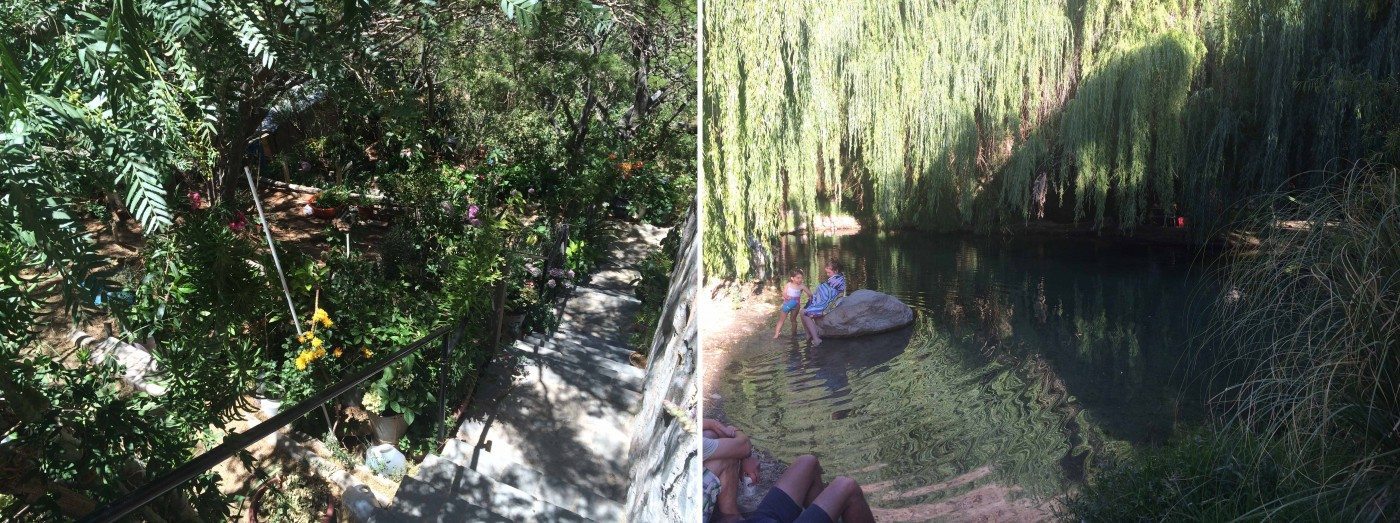

In recent decades, many people have moved to live in the Elqui valley, trying to have a life closer to nature and away from the bustle of cities. This is a common practice observed in many urban dwellers who have the opportunity to develop their professional life or create new ones in an environment close to the city, but without being subjected to its stressful pressures. Digital technologies and efficient means of transport allow this in the Valley. But can we make urban environments places of restoration too?

The design of parks in urban areas can be developed with this aim; to provide a restorative experience that can help people recover from pressures of daily life. The same activities observed in the Valley can be offered in urban parks. These include active participation in the planting and care of plants; the development of small and medium size gardens, where environmental noise is reduced by vegetation buffers that simultaneously allow temperature control; and the incorporation of local flora and fauna to their environments, which allow observation and understanding of the dynamics of the territory.

The incorporation of this ideas on how we develop urban life in the coastal cities near the Valley could certainly improve people’s wellbeing. These ideas are further supported by a strong line of research that has linked stress reduction to the experience of natural environments.

The Elqui Valley provides many ideas on how cities can develop in tune with nature, as well as benefit urban life. The nature of cities can be shaped by looking at nearby nature as well as nearby rural environments and their coping strategies. These can inform frequent questions that arise when planning and designing urban environments, such as where to grow, how much to densify and for what reasons do we develop.

What adaptive capacities do you see in the territory where your city is located that can help to solve planning and/or design issues?

Paula Villagra

Valdivia, Los Rios Region

***

References

Journal Publications:

Cepeda PJ (ed) (2008). Los sistemas naturales de la cuenca del Río Elqui (Región de Coquimbo, Chile): Vulnerabilidad y cambio del clima. P. 13-37 (2008). Ediciones Universidad de La Serena, La Serena, Chile.

Cociña, C. (2008). Ciudadanía Rural ll // Pisco Elqui y el Campo Contemporáneo. Plataforma Urbana.

Hartig, T. (2007). Three steps to understanding restorative environments as health resources. In C. W. Thomposon & P. Travlou (Eds.), Open Space People Space (pp. 163-180). London: Taylor & Francis.

Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R. F., Losito, B. D., Fiorito, E., Miles, M. A., & M.Zelson. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11, 201-230.

Video: Managing water in Dry Land: Lessons from Elqui Valley.

Leave a Reply