about the writer

Tim Beatley

Tim Beatley is the Teresa Heinz Professor of Sustainable Communities, in the Department of Urban and Environmental Planning, at the University of Virginia, where he has taught for the last twenty-five years. He is the author or co-author of more than fifteen books, including Green Urbanism, Native to Nowhere, Ethical Land Use, and his most recent book, Biophilic Cities.

Tim Beatley

Judge a city by its birdsong

Every city can and should work to be bird-friendly, both out of an appreciation for the profound quality of life benefits provided by having birds around us, and out of a deep ethical respect for these sentient wonders that we, in so many ways, can affect for good or ill. Hearing birds is one of the joys of life and for me triggers intense memories of childhood. The songs of birds were a source of great pleasure, a calming force; they lulled me to sleep as young boy, and propelled me forward during difficult days. And the emerging research (and practice) is helping to verify these beneficial experiences. There is the Liverpool hospital using bird songs recorded by sound artist Chris Watson to calm kids (at stressful times, such as when being given shots). There is new research that shows that respondents rate images of development more highly if they also hear birdsong, and especially song from multiple birds.

I think we should start to judge the progress of cities (and my profession, city planning) in terms of the ability of residents to hear native bird song. Several of our partner cities in the Biophilic Cities Project are demonstrating the value and feasibility of such a goal or vision. In Wellington, NZ, there is a marvelous wild area in the center of the city, called Zealandia, where through the building of a predator proof fence, they are attempting to restore native species of birds., so devastated by these introduced species. The tagline of Zealandia, is “Bringing Back the Birdsong to Wellington”. Already the numbers of birds such as busy saddleback, tūī, and kākā, a charming and raucous native parrot, have rebounded (in the case of the kākā, from a low of six, reintroduced in 2002, to several hundred today), and the neighborhoods around Zealandia are seeing these birds and hearing them again.

There are many things we can and should do to make cities more accommodating for birds: bird-friendly design guidelines, use of bird-friendly glass (such as the new Ornilux line, which incorporates a UV coating seen by birds but not humans, and inspired by the strands that spiders weave into their webs to prevent birds from flying into them), lights-out programs, and work enhancing and expanding habitat in cities.

But we must also work hard to actively connect urbanites to the birds already around them. And watching and listening to birds is an important element in urban stress-reduction, and a reason to be outside and to break-away, at least for a few minutes, from the sedentary arc of lives. Recently here at the University of Virginia we organized our first bird walk directly through the campus. With the help of a more seasoned birder from our local bird club, we guided mostly undergraduate students along a pre-planned route through a cross-section of the campus (the Grounds, we call it), stopping to listen and observe. I think the students were fairly astounded at the number of bird species (we counted 17 species that day), and the quantity of birds we encountered, and they also seemed to have a lot of fun. We handed out a sheet for recording observations—mostly written but some drawn. I’m not sure whether any of those who participated that day continued to look around their environments for bird, but I am convinced it helped shift, at least for some, the ways they see the pathways, trees and buildings through which they move everyday. These are hopefully understood now as co-inhabited spaces, places where if we listen closely, and if we work hard to reduce the unhealthy noise from cars and jackhammers and leaf-blowers we might be able to hear and understand the voices of life around us.

about the writer

Luke Engleback

Studio Engleback’s work currently includes a diverse range of proposals including a Biophilic retrofitting of public realm under and adjacent to the elevated Westway viaduct in London, a major urban renewal site in East London, a ‘green’ low impact design neighbourhood in Kigali (Rwanda), a cultural centre in Bamiyan (Afghanistan), a passive haus co-housing scheme in Essex, and village extensions in sensitive Sussex landscapes.

Luke Engleback

Is there such a thing as a bird friendly city?

Since 2007, more than half of Humanity lives in urban areas, a quantum forecast to reach 70% by 2050. An economic system that, hitherto, has not placed a value on ecosystems that support us all has fuelled Industrialised urbanism, but there is a change occurring. The human value of Ecosystem Services was highlighted in the United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005), an approach beginning to inform sustainable city planning and retrofitting, for resilience to future environmental change.

Cites occupy about 3% of the Earth’s land surface, but are sustained by vast ecological footprints that extend across the globe; therefore, we might ask how should city boundaries, and ultimately, ‘urban bird friendliness’ be defined? Compared to some agricultural monocultures, cities can be very significantly more biodiverse.

The concepts of Ecourbanism (whole system urban design and retrofitting) and Biophilia (an innate tendency for people to seek connections with Nature) are central to reducing our impact on the environment. The links between human and ecosystem health have been shown in many studies. Birdlife might be regarded as a barometer of environmental wellbeing.

Urban bird life depends on its location and hinterland, as well as provision for wildlife within its fabric, so a simultaneous consideration of interventions at macro, meso and micro scales is needed, not only for ‘bird friendliness’, but for essential ecosystem services providing for all.

What does it look like?

Nairobi, capital of Kenya (area 696 km2, estimated population 3.4 million) is the most bird-rich city in the World with 604 species recorded within its boundaries (British Council 1997) of the 1080 species that may be found within Kenya. New Delhi, capital and second most populous city of India (metropolitan area 1484 km2, population about 25 million), is the second most bird-rich city in the world with 202 species recorded. It is also one of the most air polluted.

Common to both cities are extensive areas of forest/scrub and well-treed suburbs that contrast with other neighbourhoods in those cities that are unremittingly urban with little or no vegetation. Clearly, the size of an undisturbed natural habitat coupled with a network of vegetation plays a vital role in ‘bird friendliness’, but defining this term is largely subjective—for how do we define bird friendly or unfriendly, and are these the same as bird safe? It is better perhaps to see birdlife as an essential part of a wider system.

The fabled Nightingale in Berkley Square is a distant memory despite its proximity to Green Park and Hyde Park, both subject to more wildlife-friendly management techniques. However, the large area of ruderal herb and scrub on the Palatine Hill and forum in central Rome (area 1285 km2, population 2.9 million), or the native species plantings in the modernist Flamenco Park by Roberto Burle Marx, are home to a wide variety of birds, seemingly happy to be close to the rumble of traffic and large visitor numbers add to their cultural value. In the case of Rio (area 1182 km2, population +/- 6 million), the adjacent Floresta da Tijuca National Park covering 32 km2, is a prime example of designed Urban Green Infrastructure. This rich wildlife reservoir was replanted in the late 19th century on land that had been cleared for former coffee and sugarcane plantations, to arrest soil erosion and, to secure the water supply for the city.

Large scale thinking is essential, since overheating in cites leading to premature deaths, is caused by the cumulative lack of vegetation, extensive sealed surfaces, and expanses of biologically inert masonry.

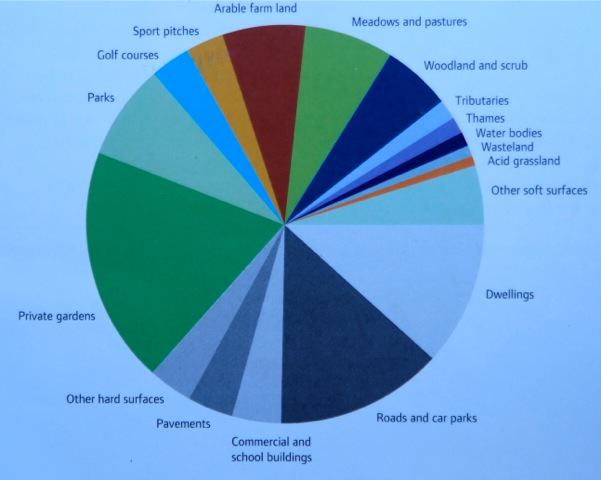

This significantly alters microclimate, creating the urban heat island effect (UHI). Work by ASSCUE in Manchester demonstrated that in the UK, a 10% increase in urban verdure could reduce the UHI by 4˚C, whilst a 10% reduction may see a rise in UHI temperatures of up to 7˚C. Investing the city fabric with vegetation not only aids biodiversity, but also to improves air quality, reduces surface water runoff, improves urban soils, effects summer cooling and energy savings, and pumps down atmospheric carbon. In London 80% of the Public Realm in London (metropolitan area 1572 km2, population >8.2 million) comprises roads and paving (GLA 2014), more of this could become vegetated or made porous. Moreover, there is also significant scope to vegetate roofs and walls.

Biodiverse living roofs support invertebrates that are food for birds, and such roofs provide habitat for birds, including Black Redstarts in London and breeding Lapwings in Switzerland. In fact, once more vegetated surfaces are provided to mitigate the urban condition, birds are needed to play their part in managing the enriched urban ecosystem. Encouraging more bird life brings with it the need to address other issues including reducing light pollution, safe roosts, and measures to reduce risks to bird life – especially collision with glazed surfaces – a danger that can kill both healthy and weaker birds alike in large numbers.

Bird friendly cities may therefore look greener, express and celebrate a range of ecosystem services, and make more efficient use of resources. Sustainable, resilient design may be more biophilic, it must certainly be more biodiverse.

What does it not look like?

They are not hard, glassy, energy intensive, impersonal urban deserts that ignore ecosystem services and have only token planting and no soul.

about the writer

Dusty Gedge

Dusty Gedge is a recognised authority, designer, consultant and public speaker on green roofs. Dusty has also been a TV presenter on a number of UK shows and makes his own Green Intrastructure and Green Roof and Nature Videos. He is an avid nature photographer and social networker posting on Twitter, Facebook and G+.

Dusty Gedge

Birds have always frequented cities. Shakespeare wrote of kites and their stealing linen in cities and of course there is the ubiquitous feral pigeon throughout the world in modern times. Whether these birds had or have merit to the human inhabitants of our metropolitan areas is an open question. I am sure that kites were a major irritant to medieval housewives, but now are celebrated when they are seen flying over London on a regularly basis.

I have recently being spending time in my small local park filming Kingfishers. This iconic bird is on the wish list of many a birder in England. A flash of blue on a river is the most we can expect to see. However in Lewisham they are bold, unlike their timid their rustic cousins. Whilst filming, the whole social and ethnic fabric of my area has engaged me in conversation. After marvelling at the Kingfisher our conversations turn to the ‘crane’ (heron) and why there is a pheasant wandering around. How and where did it come from? This is affirmation of birds being a route to encounters with nature.

The river where we are able to marvel at the splendour of the Kingfisher 15 years ago was a concrete channel devoid of anything natural except the water itself. The river was remodelled 15 years ago and naturalised. People and wildlife could once again meet as they probably did one hundred years before when millponds flanked the river Ravensbourne. This kind of change is characteristic of cities. Change is part of the very fabric of cities.

And there is change afoot. The 20th Century approach to our cities was one of sealing the surface. Concrete, steel and glass ruled. It still does to a certain extent. However many cities are embracing, and most will, the unsealing of surfaces. The notion of green infrasrtructure is taking root. There is a long way to go but it’s happening.

My own work is linked to this new green infrastructure approach. I am first and foremost a birdwatcher. My involvment in green roofs grew out of trying to protect a bird associated with the bomb sites of World War 2 and the industrial blight of 1970s and 80s. The Black redstart, along with a myriad of other birds, associated with dry stony habitats, positively thrived in this urban devastation and decline. In 1990s boom was back and developments burst out of the industrial blight. Protecting birds against the economics of new developments was a hard ‘ask’ but I, along with others, was fortunate to be able to put green roofs on the map in the UK. The protected species status of the black redstart helped ensure that green roofs were created for biodiversity mitigation. That was 17 years ago and central London now has over 179,000 m2 of green roofs. A large proportion of these are partly due to the bird.

So to me the bird friendly city of the future is intricately link to this new agenda. Rivers will be broken out of concrete to allow an encounter with a heron or a Kingfisher. Buildings will be decked with vegation allowing black redstarts to reside in the upper altitudes of our cities. Surely the bird friendly city of the future is confirmed by projects like the Bosco Verticale. Cities comprised of wooded towers and dry grasslands plains on roofs, where the dawn chorus of birds heralds the start of the urban day.

Will the human inhabitants embrace this new birdfriendly urban realm? Urbanists and modernists will probably say no! However I think the people I meet on a daily basis, whilst filming Kingfishers, would say yes.

about the writer

David Goode

David Goode has over 40 years experience working in both central and local government in the UK and an international reputation for environmental projects, ranging from wetland conservation to urban sustainability.

David Goode

Two key issues determine whether a town or city is ‘bird-friendly’. One is the range and quality of habitats that prevail, together with opportunities for food and nest sites. The second is the culture of the place, whether birds are protected, encouraged, tolerated or shot. The UK has a long tradition of interest in natural history that results today in a great abundance of bird-life in its towns and cities. But it has not always been so. In 19th Century London finches and other small birds were caught in thousands to provide cage birds. Seagulls that ventured up the Thames were regularly shot from Westminster Bridge. Times change, but our cultural attitude to nature is still crucially important today in many aspects of city life, from detailed architectural and landscape design to wider issues of urban planning and land management.

At the habitat level we are lucky that many of our towns and cities have a significant amount of greenspace and water within their boundaries. In Greater London this amounts to two thirds of the area. Private gardens alone amount to one fifth of the total area. As well as parks, cemeteries, golf courses and reservoirs, there are extensive tracts of woodland, meadow, marsh and riverside. This great variety of habitat types supports 133 species of breeding birds, along with numerous wintering species. Many of these habitats are protected as nature reserves through planning regulations, covering one fifth of the area of Greater London. This is an absolutely crucial feature of a bird-friendly city. If you don’t rigorously protect significant areas of greenspace and water against continuing pressure of urban built development the diversity and numbers of birds will inevitably decline.

A striking feature of bird populations in cities is the way that they find food supplies and breeding sites within the urban fabric. Some, such as feral pigeons and roof-nesting gulls, are not popular with city managers, but there are many species that are well adapted to city living that could easily be encouraged if we were minded to do so. Swifts are almost entirely restricted to urban areas for breeding, yet their populations are in serious decline due to the absence of suitable nest sites in modern glass and concrete buildings. One small change in architectural practice could influence this species in a dramatic way. Putting swift bricks in new buildings, or constructing towers specifically to accommodate swifts, would be a very tangible way of creating a bird-friendly city. Similar things already exist for other species such as peregrine falcon, grey heron, kingfisher, osprey, black guillemot and many others. The options are endless and every one of these has a good-news story attached.

Slight variations in landscaping techniques can have a profound effect. The number of species of birds breeding in city squares increases from only a few in hard paved landscapes to nearly twenty in those with fringing mature trees grading into shrubberies and lawns. Town parks can be improved even more. Over 50 species of birds now breed in London’s Royal Parks, a direct legacy of naturalist W. H. Hudson who first championed the concept of landscaping for birds in 1898. Bird-friendly parks result in people-friendly birds, as can be seen every day in central London.

Habitats on rooftops and green walls provide some of the greatest opportunities for enhancing grim and grey inner city townscapes, and with them will come the birds. Two final thoughts. Every city should have a major nature reserve designed for people to experience birds at close quarters like the London Wetland Centre, and we also need to take care of local phenomena such as inner-city pied wagtail roosts that bring delight to so many people.

(Much supporting evidence for these views can be found in Nature in Towns and Cities by David Goode, published by Harper Collins in 2014. Hudson’s compelling advocacy for bird-friendly parks forms chapter 14 of Birds in London Longmans Green, 1898.)

about the writer

Madhusudan Katti

Madhusudan is an evolutionary ecologist who discovered birds as an undergrad after growing up a nature-oblivious urban kid near Bombay, went chasing after vanishing wildernesses in the Himalaya and Western Ghats as a graduate student, and returned to study cities grown up as a reconciliation ecologist.

Madhusudan Katti

Is there such a thing as a bird-unfriendly city? Not if the people are bird-friendly

In North-East India, e.g., in Nagaland, one hears of villages that are eerily quiet because there are no birds to be heard. This is because, when it comes to wildlife, local people adhere to the principle: “if it moves, eat it!” Children learn to hunt early on, and even 10-year-olds armed with slingshots contribute to the family dinner table small morsels of feathered delights or eggs. And so birds have learned to stay away from, and be very quiet around, humans. Yet the nearby hills and forests hold some of the highest diversity of bird species in the world. A bird-rich bird-friendly area containing some of the least bird-friendly human settlements. There may be other such bird-unfriendly cultures elsewhere in the world, but not very many.

Can you think of a city where there are NO birds? Surely there are some pigeons or house sparrows or crows even in the most densely built-up urban center? Indeed, many of the world’s cities support scores if not hundreds of bird species, many in populations larger than in surrounding “natural” habitats. A recent comparative analysis of bird diversity in 54 cities worldwide (Aronson et al 2014, coauthored by me) found, for example, that the median bird diversity was over 110 species; i.e., at least half of the 54 cities support 110 or more species of birds, and less than 5% are non-native species. Worldwide, one in five bird species (2041 out of 10,052 known species) were reliably recorded in just these 54 cities.

Take the metropolitan area of Kolkata (erstwhile Calcutta), for example: famously teeming with people (now over 14 million) this dense urban conglomeration is home to over 250 species of birds, with not a single non-native species managing to establish a foothold competing against native urbanite birds. Other Indian megacities boast of similarly rich avifaunas, comprised of native species that have found ways to make a living amid the cities’ hubbub. Singapore supports over 350 bird species.

So what’s the secret to building a bird friendly city? Well, it depends on what you mean by bird-friendly. It seems that many birds have found ways to live in the interstices of human habitation, as long as they are tolerated and not hunted by people. Even cats, those infamous killers of all manner of wildlife, can’t keep down the sheer number of birds a city may support. Yet cats—and humans—have also driven particular species to extinction, even as others may thrive there. So when you say bird-friendly, you have to be careful to specify which birds!

None of the world’s cities were built with bird diversity or conservation as a goal. So how do they end up with so many birds? The answer is at least two-fold: (1) many birds will come looking for food and other resources no matter how strange and novel a habitat we create; and, (2) the more diverse a range of habitats in a city, the more species of birds you are likely to find. In terms of urban design, it seems that habitat diversity begets bird diversity. Cities generally provide plenty of food (even if mostly junk) for a variety of birds, and often also relatively safe habitats (despite cats). So much so that we must worry if urban habitats are ecological traps drawing threatened species to their eventual doom. The real trick then is in figuring out how to attract and support more of the native avifauna while discouraging invasives and keeping small predators (cats) at bay. And making sure cities don’t become ecological traps, but habitats where birds thrive. All of which is possible if we have bird-friendly people living in our cities.

Even in Nagaland, conservationists were able to work with local communities to completely stop the annual massacres of the threatened migratory Amur Falcons a year ago. Which should inspire us to do even better to conserve bird diversity in our cities.

about the writer

John Marzluff

John Marzluff is Professor of Wildlife Science, University of Washington. His latest book Welcome to Subirdia synthesizes research on urban birds.

John M. Marzluff

Cities should sustain their friendly attitudes with birds, else humanity forgets its past

In my opinion, all cities are bird friendly, to a degree. Even the most hardened metropolis provides a few nooks and crannies, and some bits of food that are seized upon by sparrows, gulls, pigeons, vultures, or crows. Our waste is their bread and butter.

Most cities provide much more for birds. Parks, recreational areas, and cemeteries offer birds of many species respite within the concrete jungle. Here birds can find a variety of more natural foods and nest sites. The warmth of the city may extend birds’ breeding seasons and some of the birds’ natural enemies may be rare. Where citizens notice birds many enjoy feeding them. So, supplements of food, water, and nest sites abound, especially in the less dense suburbs and exurbs that fringe the city. As a result, I see all cities as having great potential to harbor considerable populations and communities of many types of birds. And reviewing checklists of birds found in cities around the world suggests that most cities live up to their potential. For example, in continental Europe, the authors of Birds in European Cities (2005, Ginster Verlag) assessed the species richness of 16 cities, and found Lisbon to have the least avian diversity (44 species) and Bonn to have the greatest—an impressive 168 species.

But, will this potential continue to be realized?

As human populations grow and cities squeeze out all they can for human residence it is possible that urban bird abundance and diversity may decline. Therefore to me a truly bird-friendly city is one in which citizens remain vigilant of, and engaged with, their winged neighbors and take proactive steps to assure their continued prosperity.

As I recently wrote in Welcome to Subirdia (2014, Yale U. Press), to be a truly bird-friendly city, residents could:

1. Reduce the area occupied by manicured, industrial turf lawn and replace it with more diverse plantings;

2. Limit the two most significant sources of bird mortality—unrestrained outdoor cats and large clear or reflective windows;

3. Reduce night lighting, especially steadily glowing, red tower lights;

4. Encourage bird feeding and provision of nest boxes, except in rare instances (e.g., some parts of Australia) where hyper aggressive species benefit and exclude other native birds;

5. Celebrate native predators;

6. Foster a diversity of habitats within their city and the natural distinctiveness of their region;

7. Create safe connections between land and water; and

8. Enjoy and bond with the birds that thrive in the yards, parks, and commercial centers of their city.

Taking these steps will ensure that the habitats, populations, and human engagement exist so that birds can continue to adapt to city life.

Failing to sustain birds in our cities is obviously bad for birds, but it is equally bad for people. Birds add enjoyment, reduce stress, induce wonder and curiosity, and contribute to the economics of the city (houses in bird friendly locations fetch a premium price and purchases of bird feed and supplies add considerably to a city’s economy). Appreciating and understand birds can help build a broad, ecological land ethic, as espoused by pioneering conservationist Aldo Leopold. Birds can help us see our land as a community, not simply as a commodity. When we do so, we are able to love and respect nature. This ethic begins at home, but it should extend from the city to wilder places. Understanding the ecology of home informs residents about the species that do poorly in our shadow. This lesson resonates with an ecologically literate and compassionate public building a willingness to sacrifice by setting aside large, wild areas outside of cities so that the birds and other animals that cannot live with us also have a place in an increasingly human-dominated world.

Paul Shepard, in The Others (1997, Island Press), claimed that birds and other wild animals made us who we are. They were, and continue to be, important selective agents in our evolution as a species. To insulate us from their creative energy is to limit our own potential. To loose them is to loose an understanding of how we came to be. To encourage the company of birds in the city allows todays people to experience a profound taxon that stimulated our ancestors’ cultures by providing both challenge and sustenance, while always engendering curiosity and respect.

about the writer

Bongani Mnisi

Bongani Mnisi is a Regional Manager in the Environmental Resource Management Department, City of Cape Town where he manages the largest part of the City’s Biodiversity Network including four Nature Reserves.

Bongani Mnisi

A bird friendly City is…Cape Town…of course if said this I would face a lot of resistance, wouldn’t I. Rather, it is best to state that bird friendly cities do exist.

This would be a city which puts into practice agreed environmental policies; a city which takes its ecological functioning systems such as rivers, wetlands and other green open spaces forward through open green parks, proclaimed national parks and nature reserves. This city would often support greening programmes in all open spaces using native plant species. Bearing in mind that a bird friendly city would often not be without infrastructure such as roads, healthcare facilities, basic and tertiary education as well as central business districts and industrial areas, however, this would be a city where biodiversity and conservation underpins development planning. It is a city where biodiversity is a fabric on which all developmental needs are knitted.

It is important to state that to create a bird friendly city could also be championed by interested individuals who come together through various forms. This could be in the form of tree planting foundations that receive donations for trees or propagate plants/trees for greening purposes. It could also be through university programmes where masters and doctorate students carry on research to establish connections which would see previously fragmented cities reconnected through a series of ecological corridors. These corridors could be established by restoring previously disturbed environments; small individual gardens in unused open spaces such as schools, healthcare centres and even road reserves. These individual gardens alone and isolated would not add any value, but when networked together, they form a network of stepping stones that can easily connect fragmented environments.

For all bird unfriendly cities as highlighted above, the opposite is true. These cities would most likely value rapid infrastructure development with little regard of the environment on which the city itself relies. This would be a city where every square kilometre would be developed. I would call this “The Concrete Jungle”. What is not often realised is that most bird species are sensitive to various elements such as roads and electrical transmission lines. Most people would often talk about the last time they saw a certain type of bird, which is no longer in the area. However, by tracing back what the area used to be like back then compared to now, it would be easier to see why. If not, why is it that when a certain type of plant is planted, the same birds return. This is a clear indication that there are some links with habitat fragmentation and even destruction of natural environments. This would be a city where its industrial development zone is not properly followed and the level pollution is spiralling out of control. A city that lacks green and connecting open spaces.

In all this, we all have a role to play in creating environments and cities that are bird friendly. We can do this by planting bird friendly gardens adding some plant species that produce nesting materials for some birds. Creating bird baths and feeding areas where it is necessary to attract other kinds of birds which we would have otherwise not seen due to lack of plants that attract them. We also have to bother enough to watch and pay attention to our beloved pets especially domestic CATS, which are notorious bird hunters. Like with infrastructure such as roads etc., birds would often avoid homes or areas that are frequented by cats. By trying to manage cats “although it may seem impossible” we may start seeing lots of birds returning to the areas where they once occurred. Pay attention to what you are planting i.e. does it produce nesting material, is it thorny “does it lends itself to be used as a nesting area?”, does the plant have nectar and is it bird pollinated?

You have to bother because if it is not you who enjoys sighting various kinds of birds, maybe the next generation would. So do it not for yourself, but for those who are yet to come.

about the writer

Glenn Phillips

Glenn is the American Bird Conservancy’s Bird Collisions and Development Officer, and works out of New York City.

Glenn Phillips

As a New Yorker and a bird conservation professional, the question of what is a bird-friendly city is frequently on my mind, and often I think of how sustainability efforts here in one of the largest cities in the world have helped shape a more bird-friendly future. Let me start by saying that I think that cities are critical to the future for birds. Habitat loss is the number one threat to birds, by an order of magnitude, and suburban sprawl is a significant contributor to habitat loss and fragmentation. New York CIty is home to almost as many people as the entire state of Virginia. Imagine 40,000 square miles that could be devoted to unfragmented habitat and sustainable agriculture. Add in the significantly lower carbon footprint of cities like New York with robust public transit systems and the reduced heating and cooling costs of multiple unit dwellings, and cities seem pretty bird friendly from the get-go.

That doesn’t mean that cities should be given a free pass. Cities still present significant threats to birds from feral and free-ranging cats, collisions with glass, light pollution, and toxin bioaccumulation. A truly bird-friendly city must address all these threats. Prohibiting trap and release programs for cats and requiring cat owners to be responsible for their pet’s tresspasses could significantly reduce one of the largest threats to birds. Likewise, rules for dog owners should prohibit dogs from the most sensitive places and times, especially off-leash dogs, places like beaches where threatened piping plovers nest. Requiring the use of bird-friendly construction, especially adjacent to green spaces and waterways, but also along migratory corridors to key stopover sites. A truly bird-friendly city would prohibit the development of new glass box buildings, and require mitigation for existing structures. If even a few more cities followed the lead of San Francisco on this issue, it could promote the development of a huge variety of new bird-friendly glass products which could help reduce the hundreds of millions of birds killed annually in the United States. The American Bird Conservancy has been testing materials for bird-friendliness for several years, so there are already effective solutions on the market. Actively combating light pollution with fully shielded fixtures, prohibitions on vanity lighting, and strong lights-out policies could go a long way to reduce the impacts. Light pollution is implicated in raising collision rates and probably has significant impacts on migration as birds.

After generations of industrial use, cities have significant problems with persistent organic pollutants and heavy metals, that make their way into the food chain and can have significant lethal and sub-lethal impacts on migratory birds that must stop to replenish fat stores during their long flights between wintering and breeding territories. More work needs to be done both to understand the consequences and to mitigate them.

Actively making cities better for birds is the final component, and some cities, New York among them, have made positive strides. First, cities must provide healthy urban forests. New York CIty’s undertook the Million Trees Project as a way to galvanize public support, but despite the hype, the project has made real gains for urban forests, which also provide important habitat for birds, as the nuthatches and goldfinches and occasional Cooper’s hawk in the street trees outside my office window can attest. Managing natural areas in the city with the best interest of native plants and wildlife is another critical effort. New York City’s new Natural Areas Conservancy and Chicago Wilderness seek to do just that for the benefit of people as much as nature.

FInally, actively promoting the recreational enjoyment of birds and bird-watching is critical, as people must value their natural heritage in order to be moved to preserve it.

Is there a perfect bird-friendly city today? No, for sure, but cities today are generally good for birds, and with effort from dedicated individuals and conservation groups like the American Bird Conservancy, they can be better.

about the writer

Ken Smith

Ken Smith is one of the best-known of a generation of landscape architects equally at home in the worlds of art, architecture, and urbanism. He is committed to creating landscapes, especially parks and other public spaces, as a way of improving the quality of urban life.

Ken Smith

A bird report from New York City

New York City is the intersection of celebrities, real estate and birds. Apparently like their human counterparts some birds are drawn to cities. Researchers have found that pigeons, waterfowl, raptors and house sparrows are well adapted to the urban jungle. Following are some anecdotal notes on bird life in New York City.

927 Fifth Avenue—Home of Pale Male and Lola. It only figures that in New York City birds would achieve celebrity status and have their lives chronicled on television, in the news and as a topic of cocktail party chatter. Finding a good place to live in New York City is always a challenge for new residents. When red-tailed hawk, Pale Male arrived in Central Park in 1991, he first settled in an old tree nest but was driven off by thuggish neighborhood crows. But like any striving young New Yorker he soon upgraded to a building ledge above the front door of a fashionable Fifth Avenue manse. Like other New York celebrities, we were obsessed by the news stories about this eligible bachelor’s love life. There were a series of girlfriends, First Love, then Chocolate, then Pale Male reunited with First Love, who tragically died young after ingesting a poisoned pigeon. He was with Blue from 1998 to 2001 but Blue disappeared after the 9-11 terrorist attacks. Lola, his true soul mate, arrived in 2002 and Pale Male and Lola were the social “It Couple” around town. They soon ran into trouble with the building’s coop board, which was skeptical of their means of support and family connections. The board callously removed Pale Male and Lola’s nest and installed anti-bird spikes.

There was an international outcry; people protested on the street outside the building. The Audubon Society became involved and an out-of-court agreement resulted in a new engineered-nest being installed. Maybe because of the trauma, the pair failed to hatch any new eyasses following the disturbance of their original nest. “Pale Male: New York’s Most Famous Red-Tailed Hawk May be A Father Again’” declared ABC News in on May 20, 2011. After years in which Pale Male and his mate Lola produced broods of eyasses, Pale Male took up with a new mate Ginger at his Fifth Avenue address. Pale Male’s seventh and eighth mates were Zena and Octavia. In recent years many more red-tailed hawks have taken up residency in New York City and it is not an uncommon sight to see a hawk flying overhead in a city park. Apparently it is still common practice, however, to poison rats and pigeons and this leads to the unintentional death of raptors, like the red-tailed hawk, which prey on these lower food chain animals.

There was an international outcry; people protested on the street outside the building. The Audubon Society became involved and an out-of-court agreement resulted in a new engineered-nest being installed. Maybe because of the trauma, the pair failed to hatch any new eyasses following the disturbance of their original nest. “Pale Male: New York’s Most Famous Red-Tailed Hawk May be A Father Again’” declared ABC News in on May 20, 2011. After years in which Pale Male and his mate Lola produced broods of eyasses, Pale Male took up with a new mate Ginger at his Fifth Avenue address. Pale Male’s seventh and eighth mates were Zena and Octavia. In recent years many more red-tailed hawks have taken up residency in New York City and it is not an uncommon sight to see a hawk flying overhead in a city park. Apparently it is still common practice, however, to poison rats and pigeons and this leads to the unintentional death of raptors, like the red-tailed hawk, which prey on these lower food chain animals.

55 Water Street—Home of the “FalconCam“. A live webcam at 55 Water Street in Financial District of lower Manhattan transmits the lives of nesting peregrine falcons, in what is perhaps the first instance of reality TV programming. Last year it was reported that Adele, a falcon, had laid four eggs, according to Scott Bridgewood the director of building maintenance of the 54-story office building. The falcons have nested on a 14th-story ledge since the 1990s and the FalconCam was installed a decade ago to let naturally voyeuristic New Yorkers peer into the lives of other urbanites. The original breeding pair named Jack and JJaie are gone now from the nest, but like any good pied-à-terre, it was soon occupied by another real estate lucky couple Jasper and Jubliee. In 2008, The New York Times reported that some 17 pairs of peregrine falcons live in the city. The falcons nearly faced extinction in the 1960s from the use of the pesticide DDT, but since then have returned to the city, reclaiming old habitats, in a form of nature gentrification.

Battery Park—Home of Zelda the Turkey, now deceased. On Thursday, October 9, 2014, the Daily News headline read “Zelda, Battery Park’s resident wild turkey, dies after being hit by a car”. The bird was hit while walking along South Street near Pier 11 on the East Side. Zelda was a Lower Manhattan fixture, named after F. Scott Fitzgerald’s wife, who came to represent the renewal of downtown and Battery Park. I personally had seen Zelda, who was very much the bird-about-town in our neighborhood. She once posed for a celebrity photograph with my wife Priscilla. Zelda moved to Battery Park in mid-2003 and was known for roaming around the city’s open spaces. Reportedly, she even had her own Wikipedia page. Wild turkeys have become somewhat common in New York City, especially in the greener outer boroughs. While Zelda was much-loved, not all of the wild turkey population in the city is appreciated. There are about 100 feral wild turkeys (if that isn’t a redundant phrase) living in Staten Island. In a bit of overstatement, the Daily News reported in November 2013 that a “Flock of wild turkeys take over Staten Island”. The wild turkeys there wander freely in the borough’s neighborhoods, on public and private property and along the beaches. Local officials have been trying to relocate the birds for years because the birds defecate in public, stop traffic and are considered a nuisance by many residents. Because the birds have adapted to city conditions they can’t be released into the wild, where their survival would be threatened. Last year a local psychiatric hospital that didn’t like the birds on its ground, rounded up several dozen wild turkeys and shipped them off to a poultry processing plant to an ill fate. Animal activists were rightfully outraged. National Public Radio reported on November 27, 2014, “Wildlife Activists Try To Save Staten Island’s Wild Turkeys”. The conflict between humans and turkeys is still unresolved in Staten Island, the city’s greenest but perhaps least bird friendly borough.

Turkeys just get no respect. Bald Eagles, on the other hand, are much admired. Our country’s founders chose the eagle over the turkey as our national emblem and the rest of the story is history. Bald eagles have been making a comeback in New York City, where their population is the highest since the 1970s. A recent survey showed that there were 569 bald eagles in New York State after coming back from a precarious population estimated at just two living birds in 1975; the result of hunting, pesticide contamination and deforestation. I guess it is a commentary on human prejudice that we admire the birds that soar high overhead like the red-tailed hawk and the bald eagle but we don’t appreciate the ground birds like the wild turkey and the common pigeon.

1 Central Park West—Masters of the Universe. Today’s New York Times real estate section reports that a fully renovated penthouse in the Trump International Tower was recently sold for 33 million dollars, making it one of the most expensive nests in the city. The wealthy humans who can afford it love their urban aeries. These nests for the masters of the universe “birds of prey” provide spectacular views of the urban domain and a tremendous sense of power. Unfortunately we are becoming increasingly aware that architectural glass, the type that provides the sought-after privileged views, is the single biggest killer of birds in the United States. According to the American Bird Conservancy, collision with glass is claiming hundreds of millions or more bird lives annually. The New York Audubon Society has taken the lead with their Project Safe Flight, started in 1997 to provide research and awareness programs aimed at policy makers, architects and builders about the threat glass buildings pose to birds.

about the writer

Yolanda van Heezik

Yolanda van Heezik is currently exploring children’s connection with nature, and how ageing affects nature engagement. She is part of a multi-institutional team investigating restoration in urban areas, and cultural influences on attitudes to native biodiversity.

Yolana van Heezik

Is there such a thing as a bird friendly city?

To be truly bird-friendly, a city needs to have citizens who value biodiversity and influence both bottom-up and top-down decisions on how to manage the urban environment. At the level of local government, the valuing of native fauna and flora should be part of a city’s vision of its identity, and embedded in its district planning. The conservation of native biodiversity should be viewed as a priority, rather than an added cost impeding economic development.

Residents of a bird-friendly city will have an awareness and appreciation of plants and animals that motivates the management of their own gardens and neighbourhoods, as well as influencing the people they vote into local and national government. Ideally, all ethnicities would espouse the sense of guardianship of the environment that is practiced by the Māori; i.e. kaitiakitanga. This is based on a belief that there is a deep kinship between humans and the natural world. Managing the environment following a process of kaitiakitanga would create the mindset that would ensure a bird-friendly city.

Bird-friendly cities are green and leafy, and have few barriers to dispersal. Most of the urban area would support a large amount of structurally complex vegetation, dominated by native species, and spatially configured to allow connectivity across potential barriers to dispersal. The potential of natural corridors such as rivers and streams would be optimised, with bird-friendly plantings. Plantings could also create corridors out of man-made features, such as railway lines and roads.

Urban predators are a major threat to birds in cities. Pet cats are probably the most abundant predator, although in New Zealand rats and possums are problems as well. People value their pets and derive benefits from them. In order for city residents to gain benefits from their pets as well as from a biodiverse environment filled with birds, regulations would need to require all cats to be contained indoors at all times, or in a run outdoors. If all owned cats were confined it would be much easier to control unowned cats and other urban pest species.

What do bird friendly cities not look like?

Research has shown that the parts of cities that do not support a diverse avifauna are depauperate in vegetation: in the suburbs green spaces consist mainly of lawn, and small gardens have little complex green cover.

Why bother?

Without regular daily encounters with birds and other wildlife, how can we expect people to value biodiversity and develop a conservation ethic? A growing body of evidence suggests we need contact with nature for our own health and well-being.

about the writer

Maxime Zucca

MZ is an ornithologist, working at the Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux (LPO), France main bird protection NGO, as a director of nature protection department. He has written books on Bird Migration and on Paris breeding birds.

Maxime Zucca

Birds don’t like urban pragmatism

I live in Paris, and I wouldn’t say it is the most bird-friendly city I’ve ever seen. As a birdwatcher, the immediate proximity of high quality wetlands or forests would be the main reason to elect a city as such. The urban wetland of Costanera Sur, in Buenos Aires, is probably the most striking example: it is full of birds and biodiversity in general, readily accessible in the middle of the city, on the bay front. We would dream of such a wetland in Paris. Berlin, with important forested areas within the city limits, even host rare breeding species like the White-tailed Eagle. We can’t compete.

But could a city become bird-friendly, when none or very few space is available? Paris is one the densest cities in the world, with 21,000 inhabitants per km². Two urban forests, Vincennes and Boulogne’s woods, stand just out of the ancient city walls limit (what we call “Paris intra-muros”); Boulogne hasn’t changed in centuries for, and Vincennes hasn’t changed since the Napoleon. These places are interesting for forest birds, especially since wood isn’t harvested.

But let’s talk about the challenging part: Paris intra-muros, within the walls. A recent survey has shown that 65 bird species regularly bred in this entity—55 do so every year. With regards to the number of breeding birds in the whole France (277) and Ile-de-France (178), this is quite a good score.

Most of these birds will be found in green spaces, especially in the parks, those places where the contact of citizens with nature is also essential for well-being, self-harmony, health. Once this relation between nature and human well-being is understood by city dwellers, the city can quickly become bird-friendly, and the space be shared to a greater extent. This space can easily be shared inside green spaces. A part is managed for people first, and biodiversity second—it can be used to rest on lawns and benches, to enjoy playgrounds and scenery, it must of course be suitable for disabled people… But this is not discordant with several birds’ reluctance: old trees can be left if not threatening, horticulture can attract many insects. And another part of the park is managed for the biodiversity first, the humans second: herbaceous plants are cut less often and at different times, local bushes and shrubs grow densely, small wetlands are created, management is extensive… Some new parks, in Paris, are now more “bird-friendly” than old ones, even if there are smaller.

Places of water is of course important for a bird-friendly city. Paris is definitely not waterbird-friendly. The small lakes you find in some of the bigger parks have their whole banks mineralized, without any bushes, mud or reeds. Moorhens and Mallard are the only water birds able to use them regularly, and even migrant birds are not attracted to these places. Creating several small scale high-quality wetlands, who could also have a function of water treatment, is necessary in order to become more attractive.

Then, the buildings, of course: they constitute the main surface of the city! Many birds use them to breed, to hunt, to hide… Bird-friendly buildings are often the oldest ones. The new “ecological” energy-positive buildings are problematic for birds: the walls are smooth, without any holes or anfractuosities, not even a perch. To think the building as a biodiversity habitat—including the humans inside of course—is a prerequisite for the numerous urban specialists, which are mostly rupestrian birds. And of course, the roofs layer is definitively important: it is the only habitat with very few human disturbances.

A bird-friendly city is probably a city where every urban person would like to live. It’s a place where urbanism is able to design a city shared between its human and non-human inhabitants, and not only aimed to increase efficiency of human society. Maybe, a bird-friendly city is a non-pragmatic one.

I am extremely interested in this conversation as Nature Canada is developing and implementing a campaign in support of making Canada’s cities bird friendly.

Give to birds a home in your school, office building, house.

This time is for Africa to welcome the migratory bird from Europe. Birdlife International to protect the migratory birds has initiated the Spring Alive campaign which involves the children in conservation actions to the benefit of Migratory Birds.

Get involve in SPRING ALIVE

Yes, cities can be bird friendly. Georgetown, the capital city of Guyana, has over 285 species of birds in an area of six (6) square miles. Even in my tiny garden there are dozens of species. The parrots woke me up this morning. From my kitchen window I can see a ruddy ground dove on her nest with a baby. Unfortunately there is great admiration among decision makers for American style cities and we are replacing green space with concrete, glass, bright night lights etc. I agree in general with the points made by the various writers above and especially with Prof. Marzluff’s recommendations for a bird friendly environment. I am a member of the IUCN WCPA Urban Specialist group and I think this is an excellent forum for discussion and learning. Melinda Janki

Exiting Iidea that could produce a biodiversity score for cities with targets to indicate progress toward goals of increasing bird appeal!

Hello everyone!

I’ve been occupied with a few other things since writing my essay for this roundtable, including attending the Citizen Science Association’s first conference in San Jose last week. As such, I have not had time to read all the comments and respond. I am catching up now, and will reply with more information as soon as I can. Great to see the conversation thread so far, and I hope the thoughtful comments keep coming!

Madhu

Definitely, urban green spaces are like islands among the buildings matrix for migrating birds, and so they act as funnels for stopovers.

And if the size of urban green spaces has been found to be the most important variable for abondance and diversity of breeding birds through different surveys, it is different during migration times, when the territory size doesn’t matter. The park size is, to me, not the most important parameter that matters for migrants : its management, its naturality, the presence of dense vegetation and water that would inform the migrating bird on the presence of insect preys and berries, are far more important. Small “wastelands” remnants in cities are over-used by migrant birds like (european) hipolais and sylvia warblers.

What a great idea, Christine ! A ramsar-like convention for bird-friendly cities, or at least cities of importance for migratory staging of birds – maybe not only for migrating birds, but for birds all over the year !

Lots of indexes exist for evaluating the biodiversity level of a city, one of the most famous being the Singapore index – which is unfortunately too subjective in some points. There are also several nationa/Regionlal scale labels. But creating an international label for a “bird conservation city”, which would not rely on subjective assessment criteriums, but, like ramsar, on total bird numbers counted (or densities ?), why not ? Every city that would host more that 1% of the national/regional (scale dependant) population size on a species at any time of the year (either during breeding, wintering or staging) would be labelized. An idea for the next CoP CDB ?

Sorry to be late to the party. I will submit my contribution regarding efforts to make the Portland-Vancouver (WA) region more bird friendly. In the meantime, responding to David Goode’s posting, I would recommend his new book, Nature in Towns and Cities, as a comprehensive account of how cities throughout Britain have, indeed become more bird friendly. One of the most important strategies the Brits…………and David can take a large amount of credit in this regard…..is the gradual evolution among NGOs and government agencies away from focusing solely on large pristine habitat conservation programs to a more urban avian friendly conservation strategy of protecting and restoring habitat at every scale, from the locally significant sites to sites of national and international significance. The only way a city can be said to be truly bird friendly is if their habitats are protected, restored, and where necessary created from the street scape to the regionally significant sites. Mike Houck, Urban Greenspaces Institute, Portland, OR USA. I will be providing The Nature of Cities a book review of Goode’s book in the very near future, by the way.

Mark Hoestetter makes a good point here. Certainly in London migrants are regularly seen on both spring and autumn migration in parks and gardens throughout central London. As a birdwatcher I have been amazed at some of the ‘classic’ migrants that have turned up. ‘Classic’ are a group of continental migrants that if they all turn up at one place makes it a bit of a hotspot. One tiny park in Canary Wharf turned up such rarities as Wryneck, Red-backed Shrike and grasshopper warbler all in the same week. Perhaps is is the light from the buildings, however in Europe migrants tend to move on a broad front rather. In US, as I understand it they move in a more concentrated front. This brings problems for birds – although migrant death by crashing into reflected trees on glass buildings does occur in Europe, it is a huge problem in cities like Chicago and New York. This is because of the migration patterns in Eastern North America.

When I discussed the Bosco Verticale in Milan with the designer Laura Gatti, I was interested if she had given any thought to birds in the design. Of course she knew the trees would attract breeding songsters to entertain the residents. However I was interested in how a tall tree bedecked tower might become a huge migrant hotspot for passerines that had just made it over the high alps. Surely this tower of trees would be one hell of a place for migrants to rest up feed before heading to Africa. Now that would be an interesting research project.

Hello everyone!

I’ve been occupied with a few other things since writing my essay for this roundtable, including attending the Citizen Science Association’s first conference in San Jose this week. As such, I have not had time to read all the comments and respond. I am catching up now, and will reply with more information as soon as I can. Great to see the conversation thread so far, and I hope the thoughtful comments keep coming!

Madhu

This is a fascinating debate, and some really perceptive contributions from everyone. I suppose for me, the birds and city thing reminds me of the canary in the mine – a diverse city birdlife is an indicator of the health of the city ecosystem. The major move to reinvest city ecosystem services of late, helps to reconnect us with our overarching life support system.

My studio has practised a whole system approach to urban design and retrofitting we refer to as Ecourbanism since the late 1990s, and this requires some elastic thinking about scales and ingredients to create multifunctional green infrastructure. People are as much part of this complex ecosystem as birds, and our lives are enriched seeing and hearing them. I have spent happy hours looking a wheeling starlings in Rome, or busy BlackRedstarts in the old Roman ruins feeding, or just listening to the melodious blackbird singing on the roof next door – its sound seemingly amplified by reflective surfaces of surrounding houses.

Curiously, and this is very much the urban paradox, one of the most ‘peaceful’ moments i enjoyed in a noisy city was watching diverse birdlife just metres away from a busy highway in Rio de Janeiro, in the a vast modernist park designed by the great brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx. A painter who took an abstract, and essentially non spatial approach, to Flamenco Park, the key I think was use of indigenous vegetation in large sweeps. It was designed primarily for colour and texture and form, rather than plant associations although I suspect these were in mind. Perhaps this goes against the grain of the biophilic movement (which i also enjoy) of a more naturalesque style, but it shows that it is possible to unite modernism with nature in way few modernist architects with their green swards that don’t hide the buildings have done.

Whilst large numbers of people do like ‘wild’ looking areas, there are also significant communities that feel threatened by it. A recent study in London showed that people from different cultural backgrounds preferred either the structured formality and certainty of the new Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park or the more ragged ‘natural’ quality of Richmond Park. For me, a long as these spaces are suitably invested for ecosystems to function and provide quality ecosystem services, it seems that we have a choice of how we do it, and in this way perhaps we can reach out to more people, and bring them closer to Nature.

I fully agree, we need to consider planting specific types of trees to enhance the stopovers, I refer to these as “Stepping Stones”. For example, I’ve planted an (Acacia karroo) Sweet thorn tree in my garden ten years ago and since then I’ve witnessed Sunbirds, Doves and Sparrows nesting on it, PureJoy!

Please watch my video “Stepping Stones” available from http://www.caretakers.co.za

Biodiversity is and should be the lungs of all Cities. What is interesting is that most comments are inherently connected and unique only by context of each city i.e. the vegetation and climate types, the spatial planning etc. I am inspired by all the comments from stewards all over the world and this is a true testament that none of us should despair because whatever conservation efforts we are doing from any position of this magnificent world, ultimately contributes to A Global Green World!

Good conversations all around. I would also add that sometimes folks “play-down” urban forest remnants because they are too small and in a highly fragmented landscape. I would point out that many of the “interior-forest” specialists that require large forests patches to breed often forage and reside in much smaller patches during migration (stop-over sites) and during the winter. Here in Florida – we see many neotropical warblers (many are breed in large patches up north) using small urban remnants as stopover sites and winter in and around urban areas.

What we need is a clear evaluation tool for planners and developers that take into account the many ecological nuances of biodiversity conservation. Even those individual trees can be quite important to a variety of species depending on their life histories (see http://www.thenatureofcities.com/2014/08/06/the-need-to-develop-flora-and-fauna-biometric-tools-for-urban-planning/).

I’ve enjoyed all the essays on this matter, many thanks for your wonderful contributions. Using avifauna as an indicator is interesting (whether quality of human life, ecosystem quality, air quality, etc.), if only because this could help to define methods and metrics for developing cohesive policy tools/ mechanisms. With particular concern for migrating species, whose opportunities for rest and recharge continue to dwindle under land use conversions, it seems to me that united efforts and cooperation by cities located along migratory paths could play a tremendous role in supporting these wondrous creatures. Are there already organizations in place that could oversee such networking? Ramsar is a bit too specific, I guess, but would such interests match the remit of ICLEI? Other?

I think John Mazluff makes a very good point here and one that needs taken on board by the wider ornithological community.

For many in the conservation movement cities are of least importance. I sit on the EU working group for Green Infrastructure and Ecosystem Services. Many people involved see cities as of lesser importance. GI/ES we all agree will have significant wider benefits for cities – not just for birds. Ornithologists need to recognised the potential of cities for birds much more than they do.

15 years ago when my colleague undertook the first bird study of green roofs in Basel, Switzerland. The general response from the bird community in Switzerland was negative. However his results surprised them. Having been a birdwatcher all my life and for most of it in a city and also travelling to other cities around the world, I always view a city for its potential for birds. If the wider conservation movement were more inclusive about the potential for cites and hold to a perceived negative, this would help drive a positive debate for more green infrastructure and landscapes that provide ecosystem services in cities across the world – which can only be a good thing for both humans and birds.

Thanks to everyone for an engaging set of essays! Two things immediately strike me from within the texts and comments.

First, It is great to see consensus among the writers that concedes city’s are, and have been for some time, bird friendly. This is pretty obvious to the bird watcher; we often go into the city to bolster a day’s trip list. One of my favorite birding spots is a small park in the center of Alajuela, CR–I can’t remember when I went there and DID NOT get a life bird! But this is not so obvious to many US wildlife managers. I have often encountered comments such as “cities have no ecological value” or “the habitat value of cities is zero.” So, this too is part of creating a more bird-friendly city—educating the supposed ecologically literate that cities have value. Madhu’s studies give us good ammunition to make this point.

A second general comment I have is that bird-friendly cities are certainly also people friendly! My students (Dave Oleyar and others, published in journal Urban Ecosystems) showed that people in the Seattle area that live near fragments of forest (aka bird habitat) were more satisfied with their lives and gained economic benefits (increased home value) from living in these bird-friendly situations. What is good for the gander and goose is good for others, ourselves included.

Birds are everywhere, even in the densest of infrastructure and have adapted to our harsh treatment of the land, at least some birds have. I believe that all cities are “bird friendly” and I think it comes down to how we define a “bird friendly” city and what makes those cities different from others. Those that are the “friendliest” use creative ways to increase native green space, reduce their carbon footprint, and foster an appreciation for nature. We can also agree that a bird friendly city is also friendly to people with respect to sustainable living and proper city planning. I think Dusty Gedge’s work with green infrastructures and green roofs is what our cities need to contribute to a better future for the populations of birds living in and around them.

The most critical defining characteristic of a bird friendly city is not the birds at all, but the people who co-exist with them. As mentioned by many of the contributors above, people must be aware of the birds that share the city with them for a city to be truly able to sustain a healthy population of birds. In my opinion, it is with citizen science and first hand experiences that make the most impact and sparks something in people to recognize what is surrounding them. Recall what sparked your interest in birds; it was probably an experience that left you in awe and ignited you with a new sense of wonder. Such an experience enhances an appreciation of the land and its wildlife, instilling a “land ethic”, which was famously coined by Aldo Leopold. Although difficult to accomplish, understanding what is in our cities and finding ways to accommodate both people and birds leads to a bird friendly one.

I mentioned in my comment the big biodiversity study that Madhu was part of, that he also cited in his contribution. Madhu, I wonder if, at a course scale, one could correlate bird diversity data in your dataset to city-wide measures of livability, quality of life, etc. Maybe one could statistically standardize for “wealth”. May the the scale of the whole city is too coarse, and what we really need would be sub-city data, but it could be interesting start.

I am delighted that David Maddox has picked up on my comment that the diversity of bird populations be used as a measure of a city’s sustainability. Our difficulty in testing that lies not in producing an index for birds but in correlating this with meaningful measures of sustainability, liveability, human well-being and perhaps even human happiness. I am convinced that cityscapes that are rich in greenspace and nature have special qualities that are desirable. We have a great deal of information about the birds of different cities but I am not aware that any studies have yet been done to assess possible links with quality of life indicators. I believe this could be a very rewarding field.

A bird friendly city is a city with trees, wetlands, native vegetative areas intermixed with built environments that are not mirrored or reflective and that have green roofs wherever possible. A bird friendly city is also a city with clean water and air sources and policies against use of industrial fertilizers and pesticides. Urbs in hortis or cities in gardens support bird habitats and serve as stops along bird migration routes. An enthusiastic public of bird watchers with school children drawing pictures of birds and learning bird types builds an educated and appreciative community for stewarding bird habitats. While college students are asked to consider bird types and bird migration routes when designing in the city, I wonder how many city planning offices take into account birds, insects and plants in their planning. When living systems are re reintroduced into urban areas, bio diversity grows and bio diversity is key to sustaining our ecology!

Having written my first comment this morning I read with some amusement that in a barred owl has been stealing peoples hats in a park in Salem, Oregon. The person whose hats is still to be returned by the wool appears to quite relaxed if not astonished. Joggers have now been warned not jog before dawn or where HARD HATS.

Now is this bird friendly city a human friendly one when it has owl stealing peoples hats?

Article –

Taken up on David Maddox’s point we actually use birds as a quality of life indicator in UK – this was mainly geared to the wider countryside. I think it would be possible to suggest a bird indicator to equate with a quality of life indicator. However. I am not sure that this would necessarily based on number of species. As a birdwatcher, primarily, there will be a lot of species that will just not be able to make it into our cities. However quality of habitat for both people and birds might increase populations of birds that currently have limited range in our cities. One that springs to mind is perhaps the Nuthatch that needs good mature trees. The more nuthatches in a city could suggest a better quality of life for humans (greater canopy – greater shade etc).

London has been fortunate as we have good date for birds over the last 100 years. During the economic decline of our docklands and wider industry, large tracts of land became derelict and many species of birds not associated with the city took up residence. Many would argue that this would not have constituted a human-friendly city. For those of us who enjoyed there presence it was great to see them. One of the great successes of the London Biodiversity Partnership has been to try and ‘mitigate’ the loss of this land to some extent through the use of green roofs (specifically for the Black redstart). However many of the other species are unlikely to actually benefit from these types of green infrastructure interventions.

Another area I think needs to be highlighted is the spatial geography of a city. In general there is an inner core where the majority of humans work and an the outer areas. However travelled across the globe working and always birdwatching, it is generally the inner core that is ‘less’ bird friendly and you could argue it is less human friendly. An indicator may help highlight this difference in friendliness for humans and birds. Just a thought.

Picking up on another thread that runs through the responses – health – I was fortunate to visit Khoo Teck Puat Hospital in Singapore a few years ago. The hospital has many levels and besides a very large lake. Of course it is covered in green roofs and being in the tropics must of the roofs were intensive and covered in trees. There also a series of small ponds on the roofs. All are accessible to patients to some degree. The hospital administrator was very proud of the number of birds that had been seen using the hospital. There was a large panel that listed them. It was clear that she saw the vegetation as an integral part of the hospital’s mission. To help people recover and birds intrinsically were part of that ‘mission’. Ken Smith refers to bird song being used at the Alder Hey Hospital in Liverpool. I think this is a very interesting area to investigate further considering recent strategies on well being and health across the EU.

Another area I think needs to be highlighted is the spatial

Noting the observation that several make about the abundance (maybe both numbers and species richness) being correlated with the amount of green space in cities, I’d like to riff on sometime Ken Smith says in a comment” that “… achieving a more bird friendly city will lead to creating a more human friendly city.”

Could it be true that measures that indicate a bird-friendly city (higher numbers of species of birds, and more individual birds) could be an *indicator* of the human-friendly city? That is, a more livable city, in that it has more green and open spaces, that are more diverse and therefore meet more diverse human needs? If we meet the needs of more bird species we in fact also meet the needs of more people?

I am curious Madhu, is there anything in the data your group collected as part of that worldwide urban biodiversity study that suggests such a relationship?

The variety of perspectives offered here is surely a treat. Each piece has its own unique focus, yet they all complement each other to give the reader an integrated, comprehensive view of both the struggles birds face in cities, as well as current and prospective solutions.

I connect particularly well with the stories of people realizing the depth of diversity surrounding them everyday. On the campus of my undergraduate university in Pittsburgh, PA, USA, there was a breeding pair of Peregrine Falcons on one of our campus buildings. Being able to point them out to people and say “That is the fastest animal in the world flying right over your head!” always generated satisfying responses from people hearing it for the first time. Awareness is the first step in changing our society’s attitude toward urban wildlife.

It will be interesting to observe the effectiveness of planning for birds in newly urbanizing areas vs. established cities that experience a sort of “retrofitting” for birds. I look forward to reading more here!

I’m struck by the number of recurring issues and common concerns expressed in this initial set of opinions. Clearly, this is an international issue and a call for creating stronger green infrastructure in all of our cities. Many of the responders singled out the core issues of needing more habitat protection and linkage of natural systems in cities, the creation of new green spaces including green roofs, day-lighting buried or channelized streams, and generally increasing biodiversity. There are many common problems identified ranging from the threat of predators, particularly feral cats, the prevalence of light pollution in cities and the growing problem of modern glass buildings interfering with bird flight.

I’m taken on one hand with simple measures like David Goode’s discussion of “swift bricks” and on the other hand with John Marzluff’s comprehensive list of 8 strategic initiatives for a bird friendly city. And I think the reminder that both Tim Beatly and Kaveh Samiei made about the beauty that birds and their songs bring to life shouldn’t be overlooked.

Clearly my take away from this discussion is that achieving a more bird friendly city will lead to creating a more human friendly city.

Ken Smith

I am very impressed by the range of different issues raised by this question everything from Maxime Zucca on well-being, self harmony and health and Tim Beatley on urban stress reduction to Luke Engleback on the role of vegetation in amelioration of heat islands and influencing urban climate. Perhaps we should consider whether the diversity of bird populations could provide a relatively simple but valuable measure of a city’s sustainability?

Good stories too. I particularly like Ken smith’s anecdotes from New York. FalconCams are providing a whole new world of entertainment and research exposing lives full of inbreeding, infidelity, cooperative breeding and night-time hunting, none of which was dreamed of twenty years ago.