India is on a rapid path to urbanisation. While currently only 30% of India’s population lives in cities, this is changing rapidly. Plans have been recently announced to build 100 new “smart cities” across India, with an ambitious plan that includes the proposed investment of 1.2 billion US dollars in 2015. Many of these predicted future ‘smart’ cities will come up on farmland and pasture, often commons land used or managed by the local village. Some predictions indicate that 600 million Indians may live in cities by 2031.

In the urban India that is increasingly becoming our future, the focus of administrators has largely remained on infrastructure provisioning: for roads, energy, piped water, and increasingly, for internet access. The focus on a sustainable vision of planning rarely includes a consideration of green spaces. Yet the importance given to trees and plants seems high in comparison to that given to urban wildlife, which hardly ever figures in the conversation about city planning in India. Wildlife conservation remains a discussion centered on the rural and the forest, spaces that are increasingly shrinking as the city enlarges its footprint on the rest of the country. In this era of rapid urbanization, can we hope to derive a different, urban ethic of nature conservation? One that goes beyond the popular urban fetishization of nature via protected area tourism and wildlife photography, to a more inclusive consideration of how to deal with the challenges of the coexistence of the human with the wild in a city?

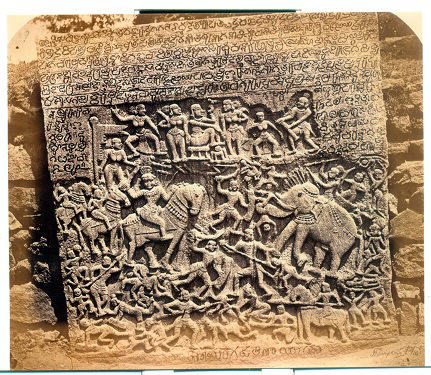

Urban wildlife plays a major role in the imagination of nature in cities. One of the most interesting narratives in the changing history of nature in the city of Bangalore can be constructed around wildlife. Epigraphic inscriptions found on hero-stones, pillars, rocks and temple foundations around Bangalore are filled with tales of hunts and wild beasts. At Kengeri, a satellite city of Bangalore at the south-west periphery, an inscription from 1060 AD commemorates the death of Rama-Deva, killed by an old boar while on a hunt. A series of inscriptions from Kanakapura taluk (south-west of Bangalore, near the Bannerghatta Tiger Reserve), describe the death variously of Rajendra-sola-valanadu from a tiger attack in 1118 AD, of Vellala Angandan from a tiger attack in 1120 AD, and of Sokka-Ilingatton and his dog in a boar hunt in 1310 AD. Hunting wild beasts was a kingly activity and a way to gain prestige: thus most of these inscriptions make it a point to mention that the victim was also a victor, piercing and killing the beast before dying. Yet the consequences of the hunt, and of death thereafter, were borne not just by the hunter but his entire family. Thus, the inscription from 118 AD states (after the death of her husband): “Thereupon his wife S’ikkavai, daughter of Vasavagamundar, entered the fire” (i.e. committed ritual sacrifice).

Deaths due to wild animal attack were not just a consequence of hunting, but occurred as a consequence of making a living in an environment populated with wildlife. An inscription of 1351 AD from Kanakapura taluk describes the death of Vira-Somaji who “having gone to tend the cattle, was attacked by a big tiger and went to swarga” (heaven), while another inscription from 1653 AD commemorates the death of Chudappa’s son Devappa, mauled by a tiger. Presumably there were a larger number of such deaths, though of people not deemed significant enough to construct hero stones in their commemoration…!

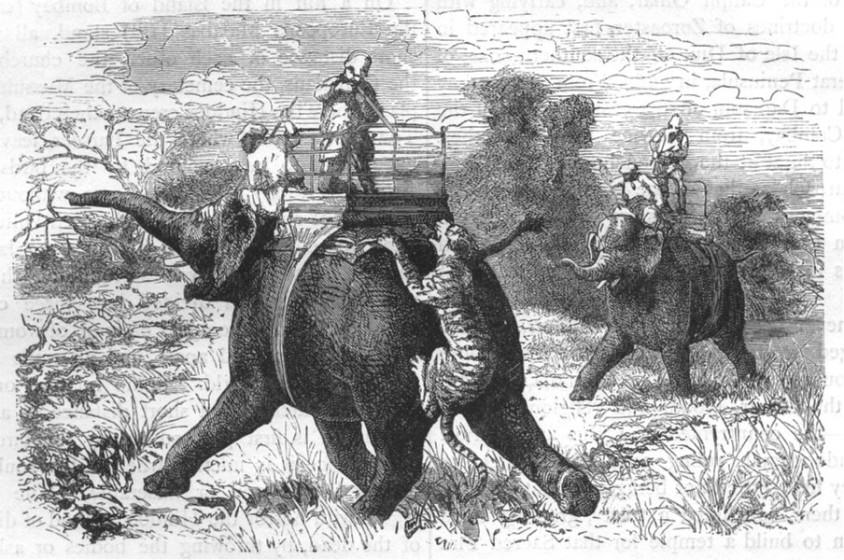

Indian rulers were of course known for their fascination with the wildlife hunt. Yet some of the most grotesque of hunts resulted from the intersection between the British imagination of the wild within the confines of the city. Urban “hunts” were a favourite pastime of the British officer in Bangalore, influenced by Indian royalty’s fascination with the wild beast as an object of hunting, used to demonstrate bravery and prowess. Yet the urban hunt in actuality demonstrated neither of these supposedly masculine virtues. Hunts in the city were conducted by British officers on horseback, armed with guns and spears in the urban backdrop of Bangalore’s race course. Tigers and other wild cats were brought in cages from the forests surrounding Bangalore, often supplied by the Mysore maharajah. An account by a British officer James Welsh, in 1811 narrates in gruesome detail the hunting of an unlucky tiger transported in a cart from the nearby town of Ramnagara. When his cage was opened on the Bangalore racecourse, the tiger immediately knocked over four native sepoys, and chased British and Indian officers around the racecourse. The tiger was eventually killed by a group of twenty peons who surrounded him with long swords and shields, despatching him with over a hundred wounds. (Meanwhile the British officer who had arranged for the hunt complained bitterly that the natives had cut a tiger which he had already speared and killed.) In the vicinity of Bangalore, the Bangalore Hunt was a family hobby. Between the 1920s and the 1940s, members of the Mysore Royal family, European and Anglo-Indian participants trampled over agricultural fields, accompanied by hounds and horses, reckless of the damage caused to local farmers.

For the natives, the dangers of wildlife were severe as the city grew, leading to an intensive period of targeted kills. During an 18 month period in 1835-1836, 2397 cattle and 14 humans were killed by wildlife, with an additional 9 people wounded in the division of Bangalore. 1 elephant, 22 tigers, 55 cheetahs, 21 leopards and 1 bear were destroyed during the same time. In 1836, rewards were instated for the destruction of wild predators, after which their number greatly decreased.

About 2 centuries later, the extermination of wildlife has been spectacularly successful. With the exception of Bannerghatta Tiger Reserve, adjacent to the southern border of the city, tigers are not to be found elsewhere (although I have seen a child of about 12 wonder if tigers lurk in an exotic Eucalyptus plantation adjacent to a road choked with traffic near my house!). Some types of wildlife are harder to confine to boundaries. Elephants, for instance. A few months ago, several schools near my home were closed for a couple of days while a herd of elephants moved through the surroundings, trampling over tennis courts and damaging lawns at one school. While we do not know what the elephants thought of such manicured green spaces, we do know that Bangalore’s newspapers were full of alarm at the “rampaging” elephant herds, with people converging in large groups and shining flashlights at the herd, further disorienting them and rendering it difficult for them to return to their familiar forest habitat.

My friend Madhu Katti (also a TNOC writer) has written about other invasions of urban habitat by wildlife in recent times, including the return of the lesser flamingos to Mumbai’s busy port harbour, and the San Joaquin kit fox to central California. These success stories are perhaps easier to handle than the challenges of dealing with a herd of marauding elephants in a city. The herd that visited Bangalore also sadly killed four people in the rural areas surrounding the city during their brief excursion. Animal-human conflicts are on the rise across India, as the city continues its seemingly relentless advance into the countryside.

My friend Madhu Katti (also a TNOC writer) has written about other invasions of urban habitat by wildlife in recent times, including the return of the lesser flamingos to Mumbai’s busy port harbour, and the San Joaquin kit fox to central California. These success stories are perhaps easier to handle than the challenges of dealing with a herd of marauding elephants in a city. The herd that visited Bangalore also sadly killed four people in the rural areas surrounding the city during their brief excursion. Animal-human conflicts are on the rise across India, as the city continues its seemingly relentless advance into the countryside.

Yet animals can hardly be to blame for this situation. The roots of the conflict seem to lie deeper, in our very framing of the wild beast as the “other”, a being to be valorized in battle, conquered in a hunt, trapped in a cage, butchered for trophies, and exoticized in print. In our smart cities, can and do expect high speed digital highways where we can browse for photographs of tigers and elephants, and watch spectacular youtube videos of wildlife at a safe distance. Yet can we see the real thing? Unless we seek out a different imagination of coexistence with nature—on her terms, as much as on ours—we lack hope for the maintenance of urban nature in an increasingly urban planet.

Harini Nagendra

Bangalore

Thank you, Colleen: this is an interesting link. We do need to interrogate our distancing from nature in a variety of ways, of which the industrial-scale factory production of meat is an important one.

An important article, and well written. Thank you, Professor Nagendra. Perhaps of interest is this related Ted Talk: http://tedxtalks.ted.com/video/Beyond-Carnism-and-toward-Rat-2

Colleen Daly