While it is undoubtedly true that thousands of cities around the world share a wide spectrum of common denominators, from garbage to biodiversity, from air pollution to sophisticated bike-path networks, or from unemployment to entrepreneurship (to mention only a sample few) it is perhaps important to examine common urban denominators that are not universal, but are shared by a significant number of cities around the world.

We could focus on cities that have a river running through them, or historic cities with ancient walls around them, for example. That would be a systematic selection that might yield interesting results.

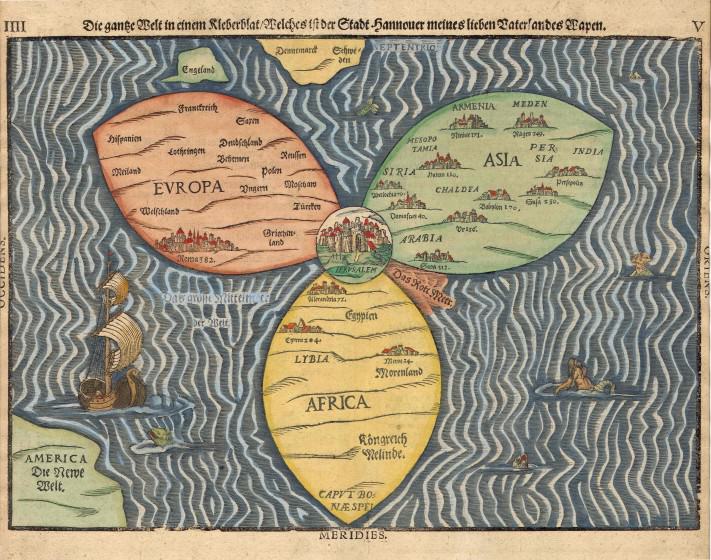

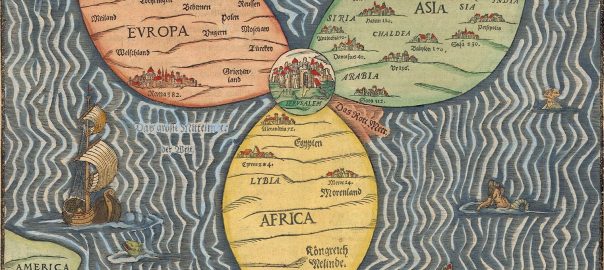

I arrived at the concept of an alliance or platform for holy cities, not by random selection, but after careful consideration of current global statistics, garnered from reliable sources.

Several years ago, at an interfaith meeting on Climate Change hosted at Windsor Castle in the U.K, Mr. Ban Ki-moon, Secretary General of the United Nations, convened faith delegations from seventeen diverse religions, and asked the religious leaders of the world to state their position on Climate Change. Amid the increasingly frustrating climate negotiations among the member countries of the U.N., Mr. Ban Ki-moon was astonished to learn that eighty per cent of the world’s population is largely faith-motivated, and while in our time (or throughout history for that matter) religion can be a catalyst of violence, he hoped to generate a shared concern among the faith communities of the world for the future survival of the work of divine creation.

After adding the well-known prediction that by the end of this century the world will be ninety per cent urban, there seemed to be a special opportunity for a center-stage role for holy cities throughout the world, together with the diverse faith communities that see those cities as important spiritual destinations.

An even more significant statistic is the quarter of a billion people on the move annually as part of a spiritual pilgrimage, traveling from one city to another. This makes pilgrimage a very significant sector of world travel, with impact on the environment from the journeys, tremendous impact on the pilgrim destination cities, but most of all, perhaps, an immense opportunity to have pilgrims enriched by their journey and by their experience, encouraged to return home more responsible citizens of the world, after leaving a positive footprint.

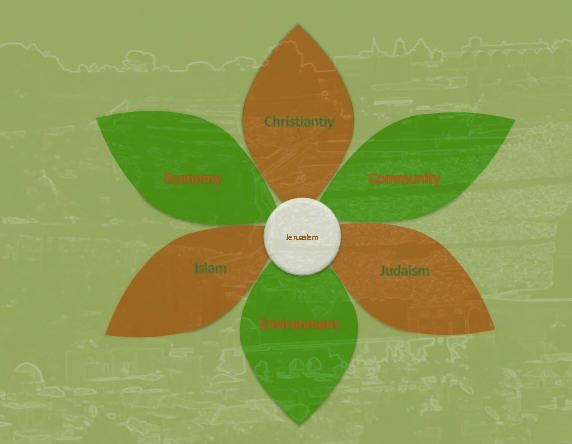

After that brief introduction to the global concept of green pilgrimage, which I was privileged to initiate at that meeting of faiths in Windsor Castle, I would like to expand the theme by considering its relevance for my own city of Jerusalem, a pilgrim destination for the three Abrahamic faiths, Judaism, Christianity and Islam (although of lesser importance for the latter, whose main destination is Mecca).

Reframing the way we look at Jerusalem in the context of pilgrimage has been a fascinating journey in itself for the Green Pilgrim Jerusalem team, and along the way we have learned that the challenges faced in Jerusalem are shared by many other pilgrim cities around the world.

How do residents feel when their city is inundated by pilgrims as festivals such as Christmas or Tabernacles approach? Do they perhaps feel they would rather disconnect from the holiness of their city, and live ordinary urban lives? How do the pilgrims feel, if they don’t receive welcoming vibes from the local communities?

We cannot disregard the fact that the three faiths that view Jerusalem as a spiritual destination have spent a lot of their energy in the effort to conquer and control the Holy City, which opens up a lot of questions, that must be addressed with sensitivity.

- Can we move from a mindset of “control” of the holy sites, to a philosophy of equity and freedom of worship in the public domain?

- Can we celebrate the roots that we share, instead of fighting for supremacy?

- Can our joint need for economic sustainability enable us to work with partners on the other side of a difficult geopolitical divide?

- Can grassroots initiatives such as ours really have a positive impact on local economies?

- Can we inspire green pilgrims to return home responsible citizens of the world, geared to greening their own communities?

- Can urban nature and the wonder of our historic landscape play a major role in our pilgrim’s progress?

The Green Pilgrim Jerusalem team began to work on the potential impact of Green Pilgrimage for Jerusalem in 2012, in the realization that here was an opportunity to reconnect pilgrims with the natural heritage of their journey, by re-examining the historic pilgrim routes and the wonderful cultural landscape on all sides of the city. Indeed, the ascent to Jerusalem gives expression to ancient tradition, going back thousands of years. The approach from the Judean desert, a breathtaking climb from the Dead Sea through the Kidron/Wadi a-Naar Basin, was the backdrop for events of importance to the three Abrahamic faiths. Israelite Prophets, Jesus and later Omar took this desert route up to the Holy City. Higher up, on the edge of the city itself is the King’s Garden, where the Kings of Israel were anointed. Over the centuries dozens of monasteries were carved into the rocks, whose monks chose a life of solitude, hermitage and humble fare, exerting a great influence on the development of Christianity during the Middle Ages. It is here, in the Qumran Caves, that the famous Dead Sea Scrolls were found, with Hebrew texts from the 1st and 2nd century CE, containing parts of the Old Testament and Apocryphal texts. Currently, the impressive structure of Mar-Saba is a pilgrim destination in its own right. This desert region was the home of John the Baptist, who initiated the custom of Baptism in the Jordan River. Nearly untouched by time, the natural landscape, heritage sites and unusual desert flora and fauna, create a unique experience for the pilgrim on his ascent to Jerusalem, and demonstrate the importance of the interface between the Holy City and the Judean Desert.

Pilgrimage routes, like ecosystems, traverse geopolitical, cultural and political borders. The experience of walking these routes on our ascent to Jerusalem can strengthen our understanding of the need to find and share common ground and mutual respect, working together for the benefit of all the communities in the region. This route gives pilgrims the opportunity to experience a truly Biblical landscape, since the local Bedouin tribes live much as did the Patriarch Abraham. The landscape, heritage and culture together create an opportunity to enjoy local hospitality in a unique ambience. The way has been opened for sustainable economic initiatives, in the spirit of “slow tourism”, developed by local stakeholders. The result will hopefully be that the local communities regain a sense of pride and ownership of their natural, built and intangible heritage.

In 2013 Jerusalem hosted “the First International Jerusalem Symposium on Green and Accessible Pilgrimage”. Representatives of Pilgrim Cities and sites shared their knowledge and celebrated the challenges they share. After this meeting of faiths, cities and organizations, the Green Pilgrim Jerusalem initiative accepted the invitation of the Order of St. Lazarus in Jerusalem, to become part of the order’s St. Lazare Holy Land organization.

Recently we have begun to examine the pilgrim’s approach to Jerusalem from the west, which would have started from the port of Acre or Jaffo in the Middle Ages, and reach a glorious climax during the ascent through the Jerusalem Hills, a rich green contrast to the sweeping desert vistas on the east side of the Holy City. The flora and fauna are quite different too, since the eastern and western approaches to Jerusalem represent the two contrasting microclimates that are so much a part of Jerusalem, a city that enjoys both worlds, on either side of the North-South watershed. Our Jerusalem teams are trying to fathom the interrelationship between the city and the urban biosphere around it, an interface which is experienced by the movement of animal populations, of pilgrims and tourists, and of commuting residents who in many cases live in the city but commute to work elsewhere or vice versa. In other words, the actual municipal boundary is of little relevance for the human and natural infrastructure in the region. The interface is, of course, exacerbated by the geopolitical issues faced by Jerusalem.

For Christian pilgrims, or for anyone who wants to follow in their footsteps (no one would be tested for their faith on route…), the approach to Jerusalem from the west would pass through the picturesque village of Ein Kerem, now a suburban neighborhood of Jerusalem. Set in a green landscape that retains flora and fauna from biblical times, hedged by ancient agricultural terraces, and watered by the winter streams of the western side of the Jerusalem watershed, Ein Kerem is a very important Christian pilgrim destination, being the site of Mary’s spring, an active water source to this day.

Ein Kerem, pastoral though it might seem from the picture above, has become a kind of battleground for the conflict between local residents and millions of visitors on the one hand, and between conservationists and developers on the other. The Green Pilgrim Jerusalem team recently offered its services to the residents and the religious institutions in Ein Kerem, to lead a stakeholder process which will hopefully create a shared vision of Ein Kerem as an important pilgrim destination.

Ein Kerem is an urban treasure, recently recommended for recognition as a World Heritage Site, whose special ambience is generated by the heady mixture of ancient traditions and faiths, telling their story through the prism of a breathtaking landscape, outstanding architecture, fascinating flora and fauna, and last but not least outstanding hospitality.

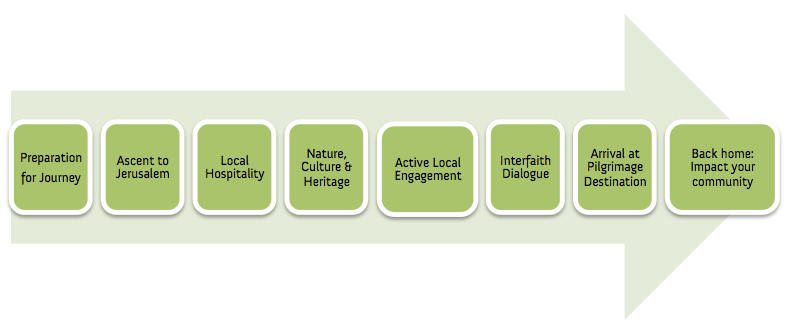

I would like to conclude with the Green Pilgrim Ladder, a concept developed together with Arch. Osnat Post. It is a concept that can be useful when planning pilgrim tourism in any Holy City, and can also be used by the members of faith communities around the world who are planning to travel to a holy city on a pilgrimage, or even as a tourist.

The beauty of the Green Pilgrim Ladder is its simplicity, while its special significance is that it places the burden of environmental responsibility on the shoulders of the traveller. The framework of travel starts in preparation for the journey, and we are asking the pilgrim not only to endeavor to leave a positive footprint on the way, but also to become a more responsible citizen in his or her own city after arriving home. Responsibility implies greater care for the environment, and greater respect for the many “others” in our neighborhood and throughout the public domain that we all share and enjoy.

The beauty of the Green Pilgrim Ladder is its simplicity, while its special significance is that it places the burden of environmental responsibility on the shoulders of the traveller. The framework of travel starts in preparation for the journey, and we are asking the pilgrim not only to endeavor to leave a positive footprint on the way, but also to become a more responsible citizen in his or her own city after arriving home. Responsibility implies greater care for the environment, and greater respect for the many “others” in our neighborhood and throughout the public domain that we all share and enjoy.

Naomi Tsur

Jerusalem

Leave a Reply