A review of Nature in Towns and Cities, by David Goode. 2014. William Collins, New Naturalist Library. ISBN: 9780007242405. ISBN 10: 0007242409. 417 pages.

The newest title in The New Naturalist Library, Nature in Towns and Cities by Dr. David Goode, is true to the series’ dual goals of “recapturing the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists” and “maintaining a high standard of accuracy in presenting the results of modern research.” Goode’s scientific background, deep personal interest in urban nature, and long-term involvement in, and advocacy for, Britain’s urban nature movement has created an entertaining and intellectually stimulating read for professional urban ecologists, planners and practitioners, amateur naturalists, and grass-root activists. While the book is specific to Britain, its descriptions of the ecological principles and the manner in which the urban conservation movement has grown over the past three decades, in Britain and beyond, are universally relevant.

Goode, with more than forty years’ experience as ecological advisor to local and regional governments, director of the London Ecology Unit, and Head of Environment at the Greater London Authority, is eminently qualified to document the urban conservation movement, including his own role as exponent, in Britain and abroad. But, beyond the institutional, political, and social factors that have contributed to changing attitudes toward urban nature, what makes Nature in Towns and Cities a practical and enjoyable read is Goode’s keen knowledge of natural history dating from the time he became a curious naturalist at the age of fourteen. Nature in Towns and Cities isn’t Goode’s first book on urban nature. His Wild in London inspired a generation of urban nature enthusiasts in the mid-1980s.

The Nature of Towns and Cities

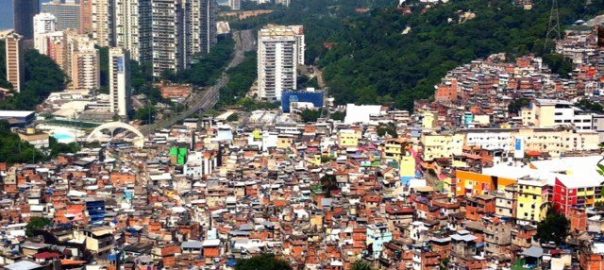

Goode opens with “Nature In A Small City”, a description of British habitats through a tour of his home town of Bath, where plants and animals inhabit “deep basements and small courtyards”, sunbaked walls where leaking drainpipes and holes in masonry provide microclimates for lichens, ferns, and spiders; Peregrine falcons utilize a church steeple; and ancient graveyards, “with their rich humus and ample nutrients, support a rich array of native flora.” He offers the reader colorful and intimate illustrations whereby even in a built-up small town, a vast array of habitats host species that belong to native sites that have been engulfed by urban development and other species that are utterly unique to the urban scene where wildlife and plants live “cheek by jowl” with people. Bath, as a template city, represents a microcosm that is representative of similar towns and cities across Britain where densely built up cities, surrounded by suburbia, offer a patchwork of green spaces, wetlands, streams, rivers, and green corridors. All of these special habitats yield an amazing amount of biodiversity from city centers to the surrounding rural landscape.

Organization of the text

Two themes run throughout the book: scientifically sound descriptions of urban natural history through an ecological lens and a detailed recapitulation of the growth of the urban nature conservation movement. In “Urban Habitats” Goode methodically describes the ecology of “encapsulated countryside” woodlands, meadows, marshes, heathland and hillsides that have been subsumed and form a remnant of the surrounding rural landscape within the urban matrix. He describes the biota, both native and non-native, that has colonized canals, cemeteries, abandoned and active railways, post-industrial landscapes, “new” created wetlands, and concludes with more prosaic urban parks, squares and cemeteries. Goode provides examples of the influence of socio-economic and political factors in shaping urban habitats. For instance, he describes the manner in which “encapsulated woodlands” were transformed following the industrial revolution and in response to changes in transportation, particularly the national railroad network, and abandonment of traditional coppicing following adoption of coal for residential heating.

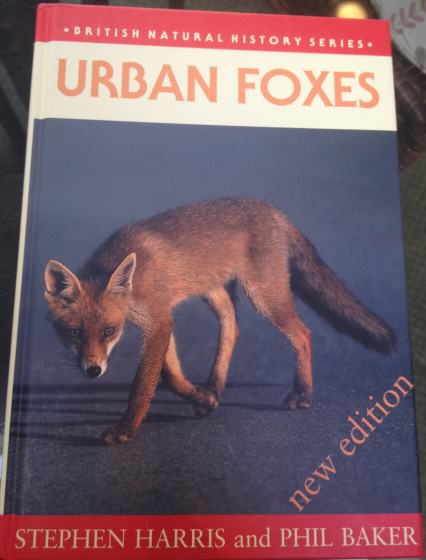

“Colonisers And Specialists” focuses on: birds new to the urban scene—“a motley crew” of opportunists; badgers and foxes; and pigeons, sparrows and swifts. A passion for urban nature, citizen science, keen natural history observation, and detective work are all illustrated in descriptions of a changing lifestyle of urban badgers since they attained protected status in 1973. What started as a colony of badgers concentrated in a small graveyard in Bath is now a badger population occupying more than 400 cities and towns across Britain, taking advantage of myriad habitats from wooded banks and gardens to golf courses. Anyone engaged in urban canid-human interactions will recognize challenges of managing the explosive colonization of urban foxes throughout Britain. The use of “swift towers”, “swift-bricks”, and nesting “boxes” in new building construction or retrofit projects will also resonate with those who have worked to introduce or reintroduce swifts into the urban environment.

I found “Post-Industrial Ecology” to be especially interesting and relevant given the modern rush to repurpose brownfield sites for new industrial development. Goode makes a strong case for investigating the ecological value of post-industrial sites, no matter how contaminated, before proceeding to industrial reuse. Goode describes how Buglife, one of the myriad NGOs at work protecting brownfield sites for their unique ecological values, created a best practices guide for planners and developers that describes the importance of invertebrate species and the benefits of ecological landscaping to protect them. He also provides several examples where endangered or threatened species, with their narrow ecological requirements, have colonized highly alkaline or acidic sites in a “Tour of Britain’s Wastelands.” Goode describes the importance of gravel pits, disused wharves, canals, and railways for providing a patchwork of plant communities that offer a range of successional patterns within the urban matrix. He argues that urban “wastelands” are the “essence of urban ecology.”

Urban nature conservation

“Urban Nature Conservation” traces the changing philosophy regarding the role of conservation in the urban context, a shift he persuasively declares as “one of the most important ecological movements in the past half-century.” He follows the urban conservation movement from establishment of the Nature Conservancy in 1949—to protect the “gems of British wildlife” when little or no attention was accorded urban nature—to the eventual recognitions of the value of nature to humans and their longing for connection to nature where they live, work and play. Eventually, these shifts led to an explosion of interest in urban nature conservation. Goode recounts the origins of local natural history societies that sprang up during the Victorian era in cities such as Liverpool, Manchester and Bristol.

“Urban Nature Conservation” traces the changing philosophy regarding the role of conservation in the urban context, a shift he persuasively declares as “one of the most important ecological movements in the past half-century.” He follows the urban conservation movement from establishment of the Nature Conservancy in 1949—to protect the “gems of British wildlife” when little or no attention was accorded urban nature—to the eventual recognitions of the value of nature to humans and their longing for connection to nature where they live, work and play. Eventually, these shifts led to an explosion of interest in urban nature conservation. Goode recounts the origins of local natural history societies that sprang up during the Victorian era in cities such as Liverpool, Manchester and Bristol.

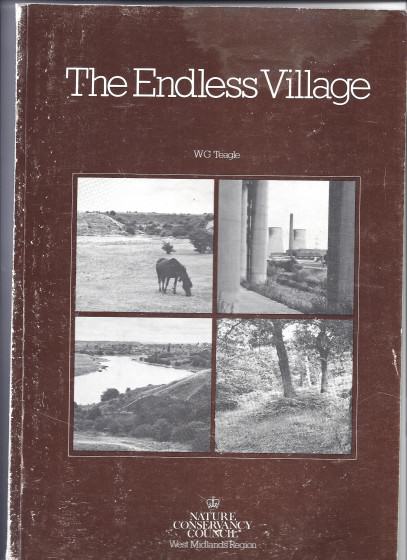

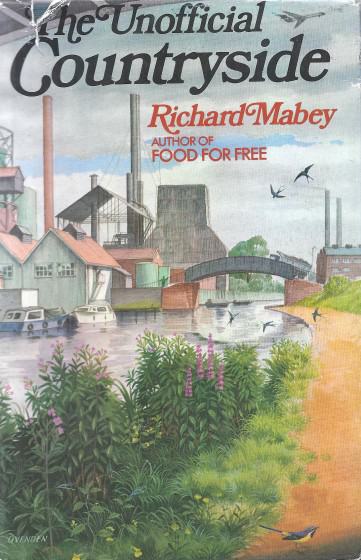

In the post war era many of these volunteer, amateur societies turned their attention to protecting urban natural areas. In the 1970s professional urban planners and landscape designers turned their collective attention to urban areas. Goode gives a great deal of credit for the surge of interest in urban nature to Ian McHarg’s Design with Nature, Richard Mabey’s The Unofficial Countryside, and contributions from the U. S. in the form of John Kieran’s Natural History of New York City (1959). But it was The Endless Village, a publication of the Nature Conservancy Council (NCC), that Goode argues “changed the rules overnight” by dispelling the myth that cities represented “ecological deserts.”

The 1980s: time for action

Anyone who has worked on urban nature conservation will relate to the assertion that, in the 1980s, urban conservation went viral across Britain with local conservation agendas leading the way. Goode uses a fight over a scrap of disused railroad property, the Gunnersby Triangle, to illustrate the rise of “Friends” organizations dedicated to the protection of small, locally important nature sites. A site of little ecological value in the traditional sense, the Triangle nonetheless became a cause célèbre due to its importance to the local population. Today it’s one of the London Wildlife Trust’s most important urban preserves. The 1980s saw an explosive growth of urban conservation groups and the integration of urban nature into formal urban planning schemes across Britain, a pattern repeated in the United States.

Urban planning

In “Urban Planning” Goode describes his own work as London’s first ecologist for the Greater London Council which was created in 1982. Goode and his ecological team were tasked with three primary functions: developing policies for ecological and nature conservation for London and the surrounding boroughs; establishing an ecological database for London; and providing ecological input and advice on issues related to land use planning and management of publicly-owned land. The team published a number of influential “nature conservation guides” for London and its surrounding boroughs which serve as excellent planning templates to this day.

Creating new habitats and planning for nature

Going above and beyond their mandate, Goode and his colleagues also participated in the development of ecology parks and nature centers. A premier example was the creation of Camley Street Natural Park which demonstrated the feasibility of creating a new wetland park out of what had been a derelict coal tip adjacent to the Regent’s Canal, literally a stones throw away from King’s Cross tube station. Not only did the creation of Camley Street demonstrate that new habitats, in this case a wetland, could be created amidst the most urbanized of urban environments but it also showed how a bit of green could be provided for children occupying nearby low-income housing. Camley’s success sparked urban revitalization projects across Britain and was the inspiration for similar efforts in Portland, Oregon and elsewhere in the United States.

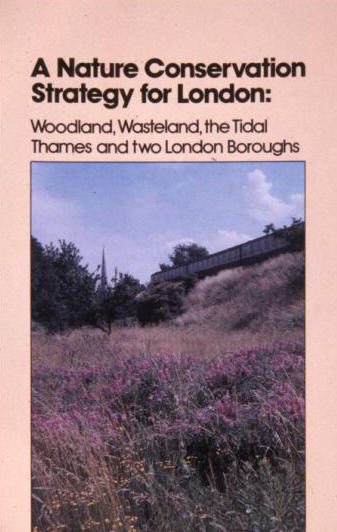

Nature in Towns and Cities includes an overview of the many international conferences, publications, and key innovators who succeeded in bringing the urban conservation movement into the mainstream. Goode also describes the evolution of London’s Nature Conservation Strategy, which, for the first time, introduced nature conservation as part of land use planning for London. The process the team of ecologists employed to inventory almost 2,000 sites not only painted a comprehensive picture of the city’s ecology but provided a template of a rigorous science-based approach to documenting the ecologically significant landscapes that is as relevant today as when they undertook the process in 1982.

One of the London Ecology Unit’s most important contributions to urban nature conservation was the development of a three-tiered hierarchy of ecological sites: London-wide; Borough-wide; and Local. Their work identified over 140 “Sites of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation” (London-wide). Surveys were also performed for 31 of the 33 London boroughs that resulted in the establishment of 1,300 “Sites of Borough or Local Importance” that together with sites of Metropolitan-wide significance represented almost 20 percent of the London area’s land base. All of this information has been described in thirty-one Ecology Handbooks published between 1985 and 2000, which constitute partial basis London’s biodiversity strategy today.

Access to nature, Biodiversity Action Plans, green infrastructure, ecosystem services, and new ecological landscapes

A conundrum for cities across the world is how much urban nature and greenspace is enough? What, in Tim Beatley’s Biophhilic Cities parlance is the “minimum daily requirement of nature?” Do we assess access to nature in hectares per capita, in quality of habitat, or rarity of habitat? One approach Goode describes is a national accessibility to nature standard developed by Natural England, which recommends at least two hectares in size within a five minute walk from home and at least one hectare of a site with the quality of a Local Nature Reserve per 1,000 population. He then describes London’s “Areas of Deficiency in Access to Nature”, which planners are using to identify where ecologically important sites can be improved, where points of accessibility can be expanded, or where new sites need to be created.

The final chapters cover a host of emerging concepts in urban ecology including valuing nature’s ecosystem services and the creation of large new urban wetlands such London’s Wetland Centre which attracted 135 species of birds in its first year after construction. Nature in Towns and Cities ends with a description of the newest effort to introduce greenspaces into city centers through the creation of green roofs.

Whether you share The Guardian’s assertion that Nature in Towns and Cities is “probably the finest work on urban ecology ever written” (December 6, 2014), there is absolutely no doubt you will agree that it’s an essential addition to any serious urban naturalist’s library and an essential and inspirational guide to planning for urban nature in your own city, town or region.

***

Rating Nature in Towns and Cities: I highly recommend the book to the lay audience, urban planners, park planners, urban conservation advocates, and natural resource managers. I give Nature in Towns and Cities a five (flawless and fantastic) in The Nature of Cities parlance, even though some might find the Britain-centric nature of the book to be a slight disadvantage.

The book is full of high quality color photographs that illustrate the text. There are also excellent graphs, charts, and diagrams that accompany the quantitative oriented text. It’s hard to imagine what Goode might have left out, given its comprehensive nature. Even though these are evolving concepts he covers the ecological importance of green roofs, green infrastructure and the concept of ecosystem services. His references to important people and publications in the urban conservation movement provide seasoned veterans with inspiring reading and new-combers with motivating material to urge them into action in their own cities or towns.

Mike Houck

Portland

Add a Comment

Join our conversation