Since moving from Edinburgh to London, I have greatly missed my bicycle commute along the former’s Union Canal. There are similar routes in London, but they’re unfortunately not on my way to work. I have always sought out such corridors and they have sometimes influenced my destinations. In response to the “Why are you interested in this position?” question in a job interview, I once admitted that getting to work via Montreal’s Lachine Canal was a big draw.

While I’ve long been aware of the positive effects of daily opportunities to get away from traffic and closer to some form of nature, it is only recently that I have given serious thought to the wider significance of green transport corridors in cities. I have written previously about how urban landscapes convey forceful messages concerning the nature of cities and the role of citizens. In that article, I described how certain landscapes can invite citizens to collaborate with nature in ways that make cities more socially and ecologically resilient. The ‘Inviting Landscape’ in question is most typically a neglected space that is transformed into a garden or pocket park—but what about the landscapes we travel through en route to our daily destinations?

Experiencing the city through its transport infrastructure

In my quest to locate Inviting Landscapes (as part of my PhD research), I journeyed to almost every corner of Manchester. If you’ve ever been there and noticed the elevated motorway running through the city centre, it will come as no surprise that Manchester’s planners have not always considered the needs of pedestrians and cyclists when designing transport infrastructure; there are some terrible roads from a cycling point of view. Fortunately, Manchester also has cycleways and footpaths (and, increasingly, paths shared by cyclists and pedestrians) and I set out to navigate these. As I moved through Manchester’s less visible transport infrastructure, I became increasingly conscious of the significance of transport corridors in defining perceptions of the city. I once spent a childhood holiday on a canal boat and although cars must have crossed bridges over our route, I thought for many years that I had been to places where the streets were water. I sometimes come close to reliving that experience when I arrive in new places via green corridors. It gives me a different sense of my destination and of the city overall.

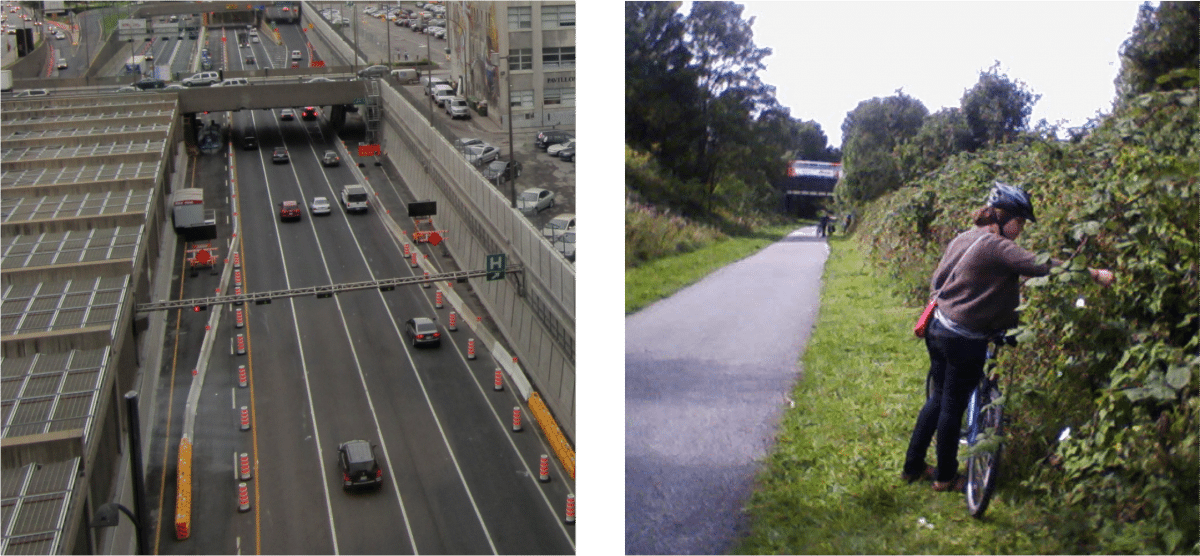

Transport infrastructure takes up a lot of space in cities. Road networks and car parking cover huge areas of most cities and therefore tend to be key features in the urban landscape that most of us carry around in our heads. Such a grey and monotonous landscape, with little sign of nature or people (other than those encased in cars), constitutes a major part of many people’s daily experience of being outside. Large scale and imposing infrastructure is characterised by obduracy (Hommels, 2005)—that is, it feels like it will be there forever and we mere humans have no capacity to change it.

But moving through a city along a footpath or cycleway, a place of wildflowers and birdsong may reveal itself. One might graze on berries if hungry and enjoy the microclimate of a well-vegetated corridor on a hot day. Such corridors provide health and well-being benefits for people who use them (Tzoulas et al., 2007), and the multi-functional aspect of connective green infrastructure, with its social value in terms of recreation and movement networks, has been recognised in the practice literature (Town and Country Planning Association, 2007). For people who consistently use green corridors, the regular contact with nature also helps to begin to conceive of the city as embedded in nature—as part of an ecosystem, or a social-ecological system, where such green infrastructure is the norm.

Green transport routes provide everyday contact with nature—and more

A key feature of this movement among everyday destinations is that it is not a recreational foray outside the daily lived experience of the city, and accessing it should not require setting aside time and other resources. I was interested to hear mention in a recent TNOC podcast of the potential of linear parks to increase equitable access to nature. I would emphasise that attending to their transport function further enhances this potential and may serve other functions, as well. Here in London, a community leader in Tottenham has pointed out that good cycling infrastructure along the River Lea would increase access to jobs as well as to nature for people who find other forms of private and public transport too costly.

That green transport corridors are part of their users’ daily lives, as well as natural places close to home for the many people who live along them, facilitates the engagement of citizens interested in looking after them. However, more efforts are required to extend the invitation to engage to both users and stewards. The UK is relatively blessed with alternative transport networks because of a tradition of footpaths and protection of rights of way. But in recent years, the same lack of care that has affected other urban landscapes has made green corridors uninviting to many people. If people are fearful or uncomfortable about using these areas, none of the benefits described above will accrue.

Making green transport infrastructure more inviting

Users of green corridors in Manchester spoke to me about some specific problems that seemed likely to inhibit use. They described how sections of canal towpaths and footpaths/cycleways were very isolated with few “escape routes” and uncertainty about possible obstructions around the next bend (often related to inadequate maintenance).

As I moved through these corridors on foot and on bicycle, I noted that the walls and fences and barbed wire separating these pathways from the surrounding neighbourhoods seemed designed to keep bad things in. They conveyed a message that the natural corridors of Manchester were dangerous places from which neighbours needed protection. A key moment occurs when deciding whether to enter the corridor, and inviting and uninviting entrances are an obvious factor.

There are also many examples of places along routes that make it unclear where to go next. One arrives at a dead end or there is a lack of signage—and natural corridors do not appear on the standard online GPS systems that people increasingly use to plan their routes. In other cases, the path is suddenly interrupted by infrastructure hostile to pedestrians and cyclists. It is clear that green and active transport routes are an afterthought, an add-on, rather than a core part of the city’s transport strategy.

Local government should invest in developing and maintaining the natural connective tissue of the city. In the same way that significant investment is made in arterial roads because they are believed to serve everyone and to connect up vital places, so inviting connective green infrastructure should be supported. The canals, footpaths, and cycleways that provide routes for active transport should appear prominently on maps and signage. Whole systems should be indicated when possible, even when portions of them are currently inaccessible, in order to enhance system understanding, and to encourage thinking about connecting up fragmented corridors.

Moving more than people along social-ecological corridors

It is also worth thinking about how people moving around green corridors may be moving more than their own bodies. The October 2014 TNOC Roundtable raised some questions about the capacity of urban green corridors to contribute to habitat connectivity. Can people in these corridors help to enhance this connectivity?

As Andersson (2006, p. 3) points out in relation to maintaining spatial resilience: “There are two aspects of connectivity, the continuity of a certain habitat (structural connectivity) and the possibility for organisms to move within or between patches (functional connectivity).” The important thing is that they find a way to move, and sometimes people can facilitate this. A wildlife conservation manager discussing how increasing urban permeability would help species migrate and therefore survive climate change told me, half jokingly, that with respect to plants, “it might be quicker to just dig them up and move them through!” This comment has stayed with me in recent years as I have watched many citizens involved in transforming urban landscapes physically move plants around.

While most plants are still purchased and driven to private gardens (and have been known to create invasive species problems), there are more and more citizens who are moving plants in an effort to enhance social-ecological systems. They reintroduce indigenous species or create edible landscapes or plant wildflowers that make landscapes more attractive and inviting. The plants are often obtained from other citizens or community organisations engaged in similar efforts at other sites, and are frequently accompanied by the ideas and skills of the fellow citizens that bring them (often by bike and along natural corridors when possible).

It has been suggested that landscape ecology has limited applicability in cities because ecosystem processes have been so disrupted that function no longer follows form (Andersson, Ibid.). However, function perhaps still follows form, but the form is a ‘messy social-ecological system’ (Alessa, Kliskey, & Altaweel, 2009). It includes a variety of people, nature, and places bound together in a complex web of relationships. And people, with their visions of what the city is and can be, are often the ones facilitating system connections. Conventional infrastructure, which has long determined the flows of matter and energy in cities, still dominates, but people with different ideas are simultaneously carrying matter, skills, and inspiration among sites and along corridors in the context of a more collaborative relationship with nature.

The more people feel comfortable and spend time in green (or greenable) spaces and corridors, the more likely they are to use them, to appropriate them, and to look after them. Those who move in these corridors begin to see the landscape of the whole city and our place in it from a different perspective. It allows us to reconceptualise urban systems, to shift away from a focus on large-scale systems—where people and nature are largely invisible—to more human-scale, systems where the importance of what nature is doing and what citizens are experiencing and doing can be seen and supported. Efforts to expand multifunctional green infrastructure should be accompanied by visions for cultural and experienced landscapes that redefine the city.

Janice Astbury

London

References

Alessa, L., Kliskey, A., & Altaweel, M. (2009). Toward a typology for social-ecological systems. Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy, 5(1).

Andersson, E. (2006). Urban landscapes and sustainable cities, 11(1).

Forman, R. T. T. (1995). Some general principles of landscape and regional ecology. Landscape Ecology, 10(3), 133–142.

Hommels, A.M. (2005). Unbuilding Cities. Obduracy in Urban Sociotechnical Change. MIT Press.

Town and Country Planning Association. (2007). The essential role of green infrastructure: eco-towns green infrastructure worksheet. Advice to Promoters and Planners. London.

Tzoulas, K., Korpela, K., Venn, S., Yli-Pelkonen, V., Kaźmierczak, A., Niemela, J., & James, P. (2007). Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: A literature review. Landscape and Urban Planning, 81(3), 167–178.

Great post, Janice.

In the short few years I spent in Edinburgh, one of the things that struck me was that I didn’t mind walking a mile or two, because walking was made so pleasant. After reading this, I realize again how much the city’s nature corridors contributed to that, and how big a factor this is in the cities where we most enjoy and partake in walking/biking to and from places.

Your statement about feeling comfortable in green spaces leading to usage, can be applied widely. By example, in the U.S. we tend to paint white lines on the street next to fast moving traffic or patch together difficult to navigate trail systems, and then lament that no one is using them. Of course, they are not comfortable to use, or offer a more difficult experience for users than should be the case.

Your simple observations about feeling comfortable, connecting to neighborhoods, and increasing visibility and ease of use offer a good check list to planners. The truly innovative cities are certainly understanding of these points, and the rest, well, they’re slowly coming on board. We hope.