The fractal idea revisited in an attempt to make the concept clearer on a day-to-day, more visceral basis.

In my first blog for TNOC I outlined my concept of an ‘urban fractal’ and noted my fascination with the idea that “one might be able to identify patterns in urban systems that could provide a systematic model for developing cities that can always and simultaneously incorporate the essential characteristics of ecologically sustainable urbanism—and that this might be applicable across the spectrum from eco-village to metropolis.” I described an urban fractal as “a network that contains the essential characteristics of the larger network of the city” and that “Each fractal will possess nodes, or centres, and patterns of connectivity that define its structure and organisation, and it will exhibit characteristics of community associated with living processes.”

In my first blog for TNOC I outlined my concept of an ‘urban fractal’ and noted my fascination with the idea that “one might be able to identify patterns in urban systems that could provide a systematic model for developing cities that can always and simultaneously incorporate the essential characteristics of ecologically sustainable urbanism—and that this might be applicable across the spectrum from eco-village to metropolis.” I described an urban fractal as “a network that contains the essential characteristics of the larger network of the city” and that “Each fractal will possess nodes, or centres, and patterns of connectivity that define its structure and organisation, and it will exhibit characteristics of community associated with living processes.”

The ‘essential characteristics’ of ecologically sustainable urbanism most certainly have to do with physical structures and infrastructures that deliver energy and water efficiency, low-to-no waste regimes, clean air and biophysically healthy environments but those are relatively easy to describe. The hard bits are to do with the requirement that each fractal “will exhibit characteristics of community associated with living processes”. It’s hard because communities and living processes are messy, squishy, fluid, tricky to define and full of people who may have their own ideas about how to make their community.

For some time I’ve been wanting to flesh out the idea of urban fractals so that non-specialists might find it more readily understandable and to reinforce the message that this concept is not about making arcane geometric patterns but is about the patterns that manifest in the tapestry of activities and relationships that make up daily life. It’s personal and it’s political.

Urban fractals can be described in terms of acceptable metrics and there are superb analyses of the fractal nature of city form and development (notably by Salat et al and Batty and Longley) but these invariably discuss the workings of urban life in formalistic terms and, of necessity, resort to jargon. I don’t think most citizens affected by these things would make much sense of the language that professionals employ to discuss them. Too often, planning processes tend away from reification and towards generalities and abstraction and unintended alienation. As both an urban theorist and a real person, I have to admit that this preoccupies me. It preoccupies me because when one’s rhetoric is all about community engagement, and claims that an urban fractal is “a particular type of cultural fractal”, I think it should be accessible to non-specialists and, well, ‘ordinary’ citizens.

A place called Semaphore

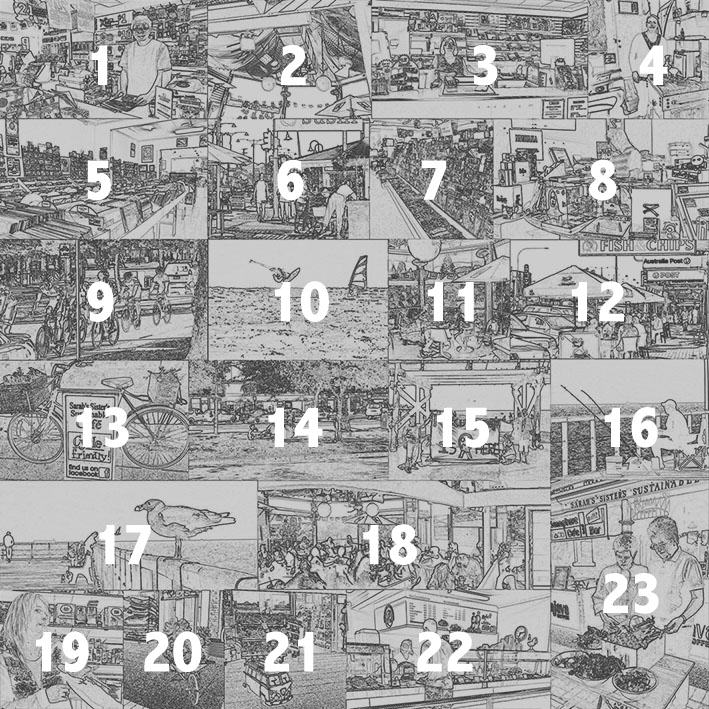

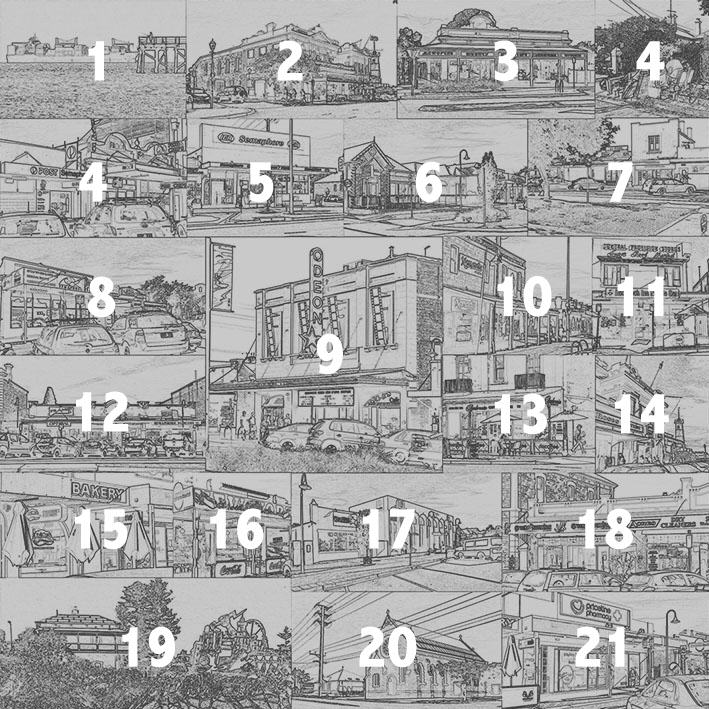

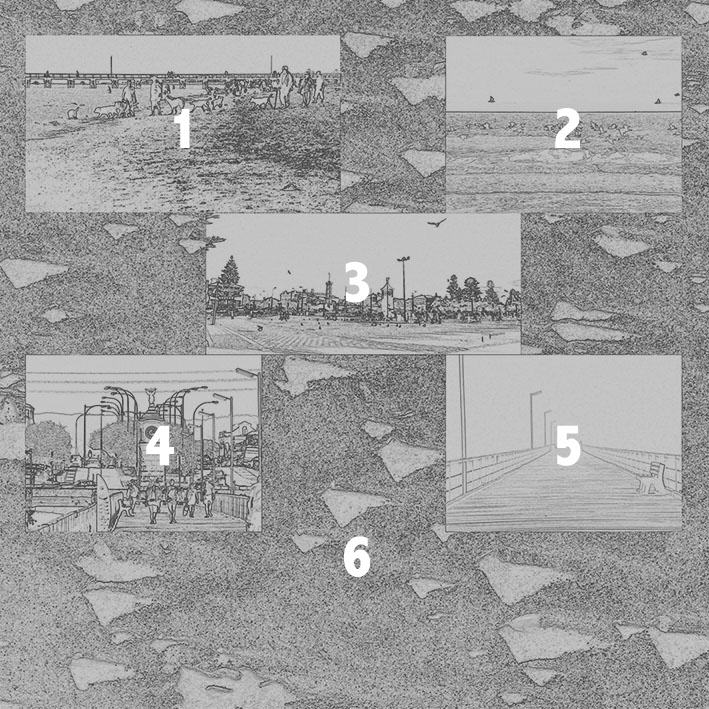

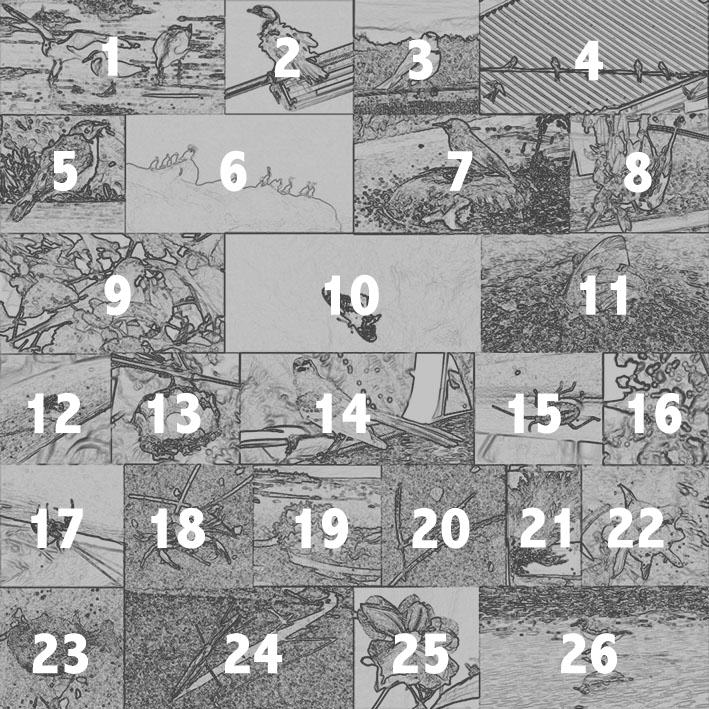

This blog is thus an attempt to describe some of the ‘essential characteristics’ of urban fractals in a way that non-specialist might find acceptable and accessible. Based on my own experience of the neighbourhood I’ve lived in for the past three years, it describes parts of the urban fractal idea using the example of a place called Semaphore, in South Australia. It is part photo-essay but the images are not generic, they are specific to a particular place. The same could be done for any neighbourhood as a way to find its fractal threads.

Snapshots of an urban fractal

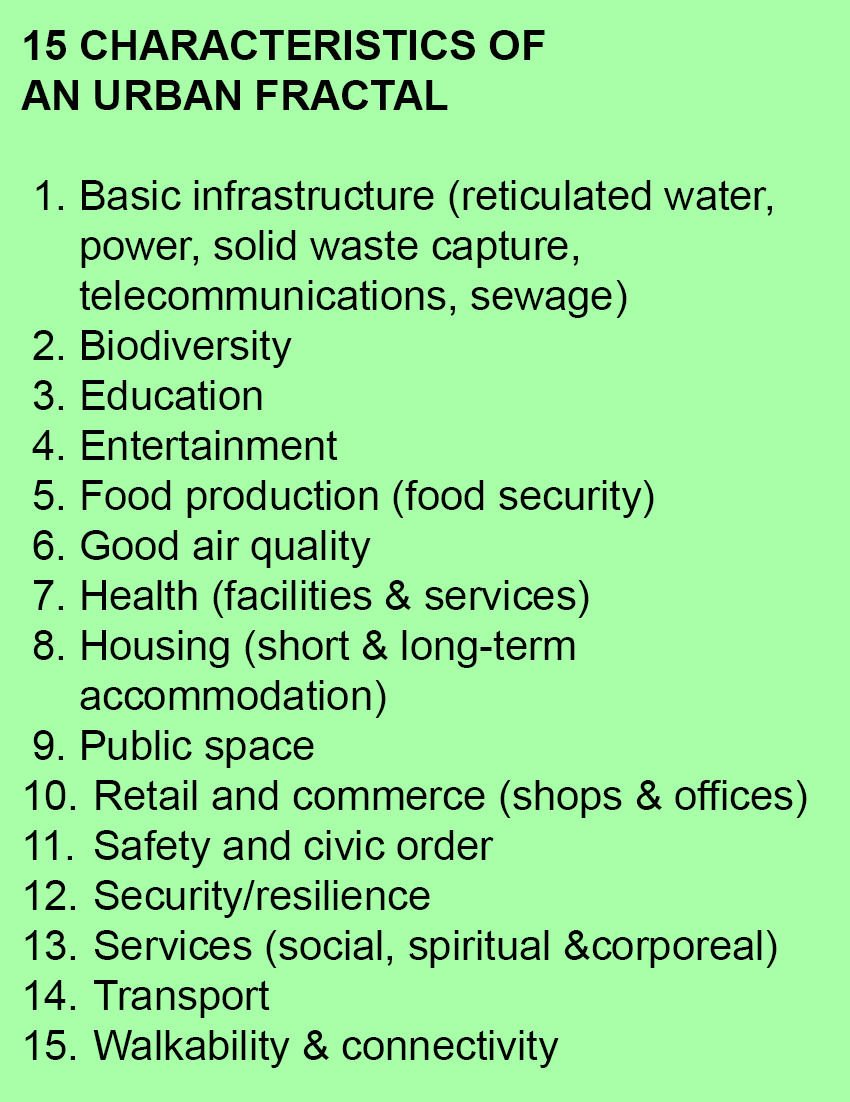

There are any number of characteristics that might be used to define an urban fractal but to try and keep the list reasonably manageable I propose the following:

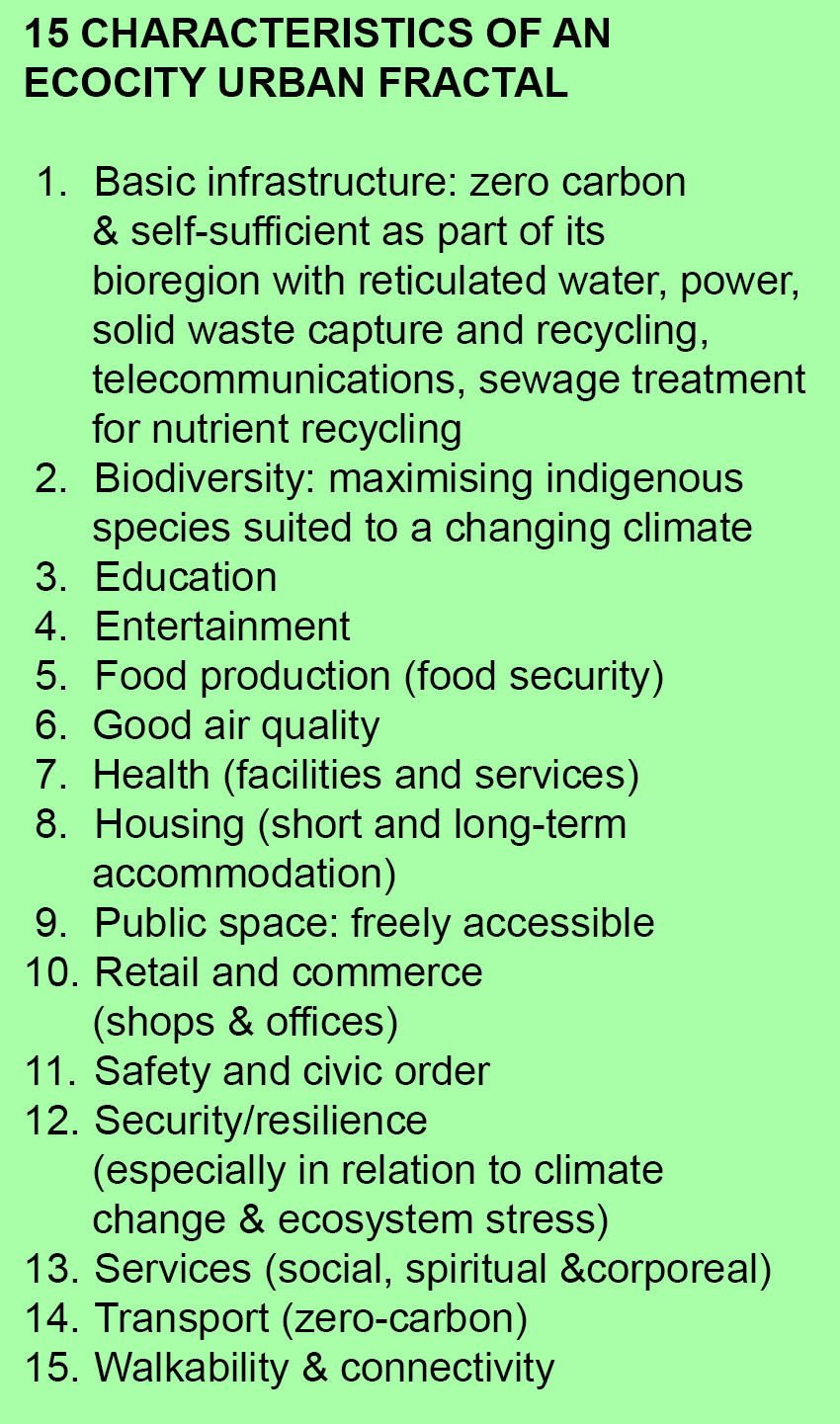

For these to become attributes of an ecocity or ecopolis, each characteristic has to be adjusted accordingly:

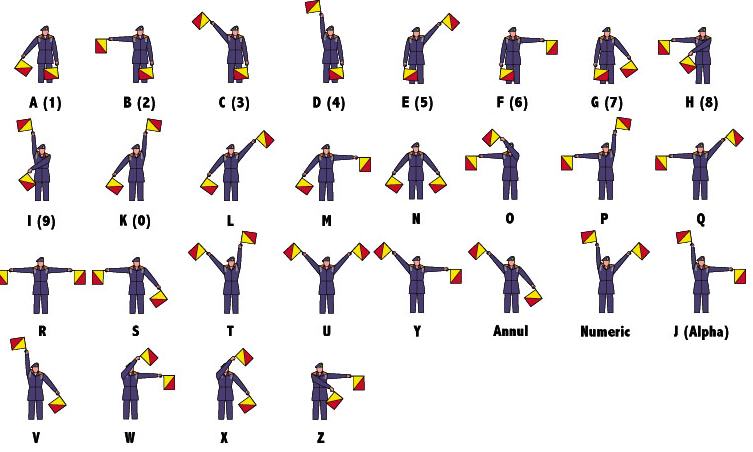

It’s the only town in the world named after a flag-waving communications system . Write a letter addressed simply to Semaphore, and there is no other destination it could be headed to (although whether modern, machine-based postal sorting systems can handle that level of simplicity is a moot point). On a reserve close to the foreshore, Semaphore boasts one of the world’s remaining 60 or so timeballs, still standing, still signalling the need to synchronise our chronometers if we want to find our longitude at sea without GPS.

Until it’s occupied, a town, village or city is not alive. Though its buildings, streets and squares may resonate with the marks of human manufacture it remains as dead as an archaeological dig, its timeball frozen until its empty vessels are filled with people doing all the messy, amazing things that people do to bring urban structures to life. Technology doesn’t make cities. People make cities. All the technology in the world can’t guarantee that things will perform as planned, act as advised or deliver as prescribed. The most advanced aircraft in the world can still be flown into a mountain.

Invisible people

I keep coming back to the realisation that the things that make all the difference, the things that make it all work, don’t show up in plans at all. The blueprints for our cities don’t show people. The professionals involved in the making of our built environment rarely embrace the engagement of the wider community in their planning processes. A lot of architects prefer that their buildings are photographed without people in the shots.

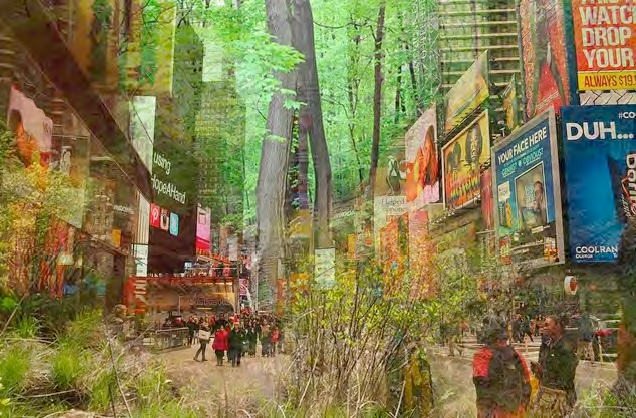

Then there are all the non-human species that help make up the populations of our cities and towns. For the most part they are ignored or regarded as a nuisance or even an enemy. Yes, I know that there are now a lot more design professionals who understand that trees and landscaping deserve more important consideration in their plans than that of merely providing decorative finishes to streetscapes or making generic green space, but I’m not convinced that they are yet in the ascendant—proof to the contrary remains elusive. And there is so much more to non-human occupation of our urban systems than that.

Very few of the human population of a city are ever asked directly about their needs and demands; some take advantage of electoral processes and other ways to influence decision-makers but true plebiscites are rare. The non-human population has no voice or representation at all apart from departments of the environment and sundry under-funded activists. In the absence of Dr Dolittle, who can present a voice for the animals? We have to make do with environmental campaigners and ecologists! The insights and information provided by them needs to be built into design and development programs for our cities and urban systems; think in terms of creating design guidelines for non-human species. No ecocity urban fractal can be complete without them. This blog only begins to hint at the wealth of life that can be found in an unassuming non-ecocity urban fractal—imagine what might be there if we were shaping our neighbourhoods with non-human species given equal weight to us.

Urban fractals are about describing society and its relationship with the environment. Thus they are inevitably about society, culture, politics and, to my own surprise, an acknowledgement of the importance of the people who are the social glue, the people who are cultural catalysts and make us laugh and cry and think, and the much maligned people who stir the pot of politics.

Although it has a strong sense of identity, Semaphore has no autonomy as a political entity. It has been subsumed as a suburb within the City of Port Adelaide Enfield, which is a relatively recent creation that incorporates previously separate council areas and has boundaries which reflect political expediency rather than any sense of place. As Jayne Engle and Nik Luka remind us: “Cities must be seen holistically as containing overlapping and nested neighborhoods.” Neighbourhoods are getting noticed. In Amsterdam, as the city’s compact centre begins to suffer from too much pedestrian traffic (in Australian car-centric cities we can only dream of such a thing) neighbourhoods are being rediscovered as a funky new tourist destinations. This reinforces the idea that the liveliness of cities is not only found in their centres but is part of their whole fabric, manifest in the local communities of neighbourhoods. We’ve known how to make neighbourhoods intuitively for generations, now there’s increasing interest in figuring out what defines and makes a neighbourhood work – and refining the concept of the urban fractal is part of that quest.

Community by numbers?

How do you make community? You can’t really prescribe it, even if products like the Green Star – Communities rating tool developed by the Green Building Council of Australia (GBCA) do an excellent job of melding business and environmental concerns with developer interests in a way that incorporates ‘stakeholder engagement’. Developed “in close collaboration with the market, including all three tiers of government, public and private sector developers, professional services providers, academia, product manufacturers and suppliers and other industry groups” the tool will assuredly help create better developments than might otherwise occur. But a cynic might argue that it is also a product of how curiously neutered political life is at the civic level. It is more about cautious market research than it is about stirring the body politic to new heights of creativity and imagination. It is nicely ordered stuff. But surely, there’s more to real life than that?

Of course, there’s probably an algorithm for it all, but if we are going to rely on any kind of professionally distanced or centralised systems to identify the patterns that inform the algorithms that shape the spaces that house the neighbourhood then we abdicate the imperatives of real community that cause people to talk to each other and explore the myriad possibilities of relationships and actions that are nascent in human society. Community, like a sense of place, is an emergent property of place, circumstance and behaviour and a computer algorithm or rating tool can’t force it into existence. Sub-cultures and communities of interest, be they chambers of commerce or knitting circles, are the grit that can catalyse the production of neighbourhood pearls. Almost any situation involving some level of conflict or difficulty can catalyse the coming together of people that begins community, and so can spontaneous mutual aid, where people cooperate to help each other out because each person benefits in some way from that cooperation. It doesn’t have to be dramatic—“The people who live along the beachside street walk each others dogs, have street parties and collect their neighbours’ bins”—and whether it’s based on self-interest or altruism really doesn’t matter if the result is “We’ve become friends and it makes it easier because everyone looks out for each other” (‘Friends sharing and caring on Arthur St’ p.3 Portside Messenger 25 March 2015 ).

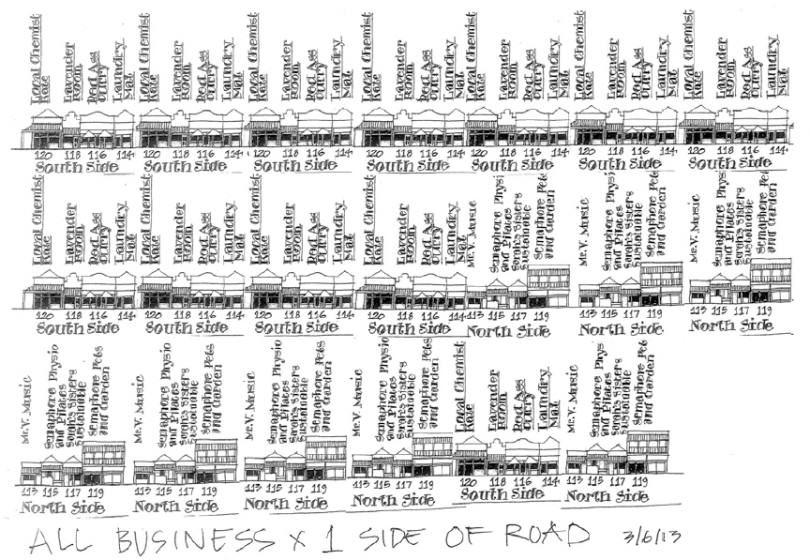

The community that I know, the fractal that supports me, is one with a main street that has almost every shop and service that Chérie and I need on a daily basis. The butcher, the barber, the newsagent, the multi-cultural cafés, the post office, the small, friendly supermarkets, the pub, the pharmacies, the takeaway Chinese joint, the record store that still sells real records, all get a visit on a regular basis; the local service station, the dry cleaner where they remodel clothes, the shoe shop, the optometrist, the physiotherapist, banks, they’re all within easy walking distance; and when the grandchildren come around there’s a playground, the foreshore and the beach. And there’s much more, including churches, schools, dentists, a sweet shop (candy store), pet and garden store, sports grounds, meeting halls, and a community garden. And there’s the legendary RSL (Returned Servicemen’s League) club with cheap curries, live music and a remarkable history.

My neighbour brought me gluten-free muffins morning as I wrote this essay.

This is but a sample of what this neighbourhood can provide. Properly speaking, it is a small town. It has a strong sense of neighbourhood. It’s the sort of place where informal discounts are common, pay tomorrow that’s OK is acceptable, where an expectation of honesty is the default condition. It’s a place where people still seem to trust each other. Even the troubled and damaged citizens living on welfare are treated like the human beings they are, rather than statistics or worse. And all the time there is a strong connection with nature, with the ever-changing sea always visible right down the end of the main street. This place is alive.

How does one design for this to happen? Is it possible?

Someone else’s perception of this urban fractal will be different. There will be shared dots in the picture but connected to form a slightly different pattern. The network of connections is very unlikely be the same for any two Semaphorians but the effect of completeness and general daily experience will be very similar. The range of possible patterns of connection is enormous (I’d love a statistician work out a few figures because quoting numbers always lends an air of authority to this sort of thing – offers anyone?) and this is part of what underpins the perception of rich diversity in a well-used place. And isn’t that true of ecosystems generally? The larger the number of potential destinations, the more potential there is for forming different connections and the richer and more diverse are the observable patterns of behaviour.

Schlumbergera bridgesii

Schlumbergera bridgesii

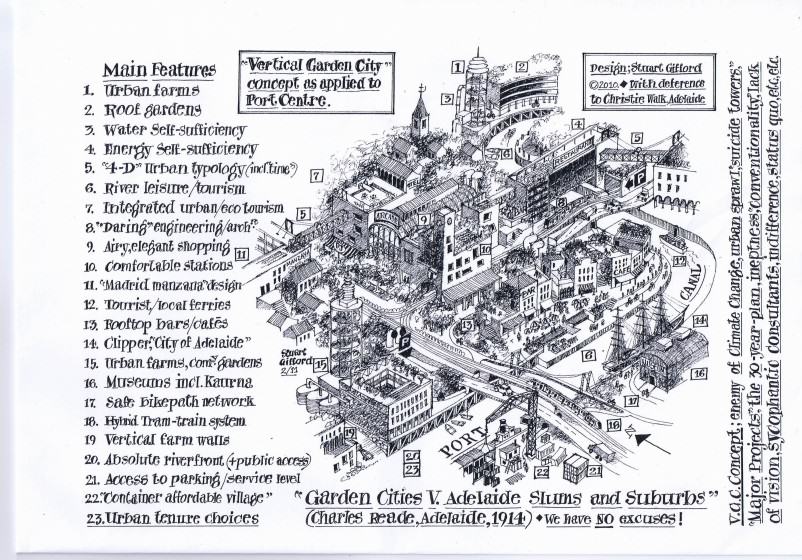

The energy of a place like Semaphore comes from people who live and work there and maintain the luxuries and necessities of daily life. The future of a place like Semaphore is determined, in part, by its history, and the course of history is disrupted by people who have dreams or despair of how it might turn out. Ordinary people are rarely ordinary. The Semaphore Workers’ Club was the home of Australia’s strongest Communist Party for many years (and arguably still is). Under the cloak of normalcy, visions stir. Operator of tills, cookers, kitchen sinks and the iconic small business of Sarah’s Sister’s Sustainable Café, Semaphorian Stuart Gifford is one who constantly tears that cloak in response to such stirrings. His drawings of the main street of Semaphore capture something of its diversity and richness of place. The industrial past of Port Adelaide is barely a mile away from Semaphore and is, in some ways, its Siamese twin. Knowing this, Stuart’s drawings of how the Port could transform into an ecological city give more than a few clues as to how Semaphore itself might be trained to develop into the kind of place that might survive this era of catastrophic climate change.

Musings on design guidelines for non-human species

When we design and build environments for particular human purposes—a school perhaps, or a sports facility—we draw on the expertise of people we are familiar with and their requirements in order to write an appropriate brief. The same should apply when we want to build in a way that actively supports, rather than merely tolerates, the needs of other species. The equation is a simple one, the basis of straightforward programming:

IF we want A, THEN we have to have B

IF we want X, THEN we need Y.

There are examples: the specification of particular species of flora to attract particular species of fauna to assist in maintaining biodiversity.

The hard thing is to find a way to give the other species priority. From their point of view, there is precious little evidence to date that we have done anything other than seek to eradicate or diminish the environment on which they (and ultimately, we) depend. A major cultural shift is needed and it needs to be a shift that does not rely on monetised values of nature for its legitimacy. The market is slippery and unfair and gives very high value to things and processes that create massive environmental (and social) damage. In the perverse world of the market, whether free, controlled or clandestine, the last tigers, elephants—you name it—are being killed because they are so valuable in monetised terms. As the number of dodos diminished, they were valued ever more highly by the market. The cultural shift has to be one that recognises the intrinsic value of other species, not their price in the market place.

In the same way that everyone is a distinct individual, every community is unique. It is special within itself, but like every living system on the planet it dies or thrives in response to objective conditions and the level of nurture it can obtain from its environment. As our species has grown ever more invasive and manipulative, so those objective conditions have become increasingly dependent on human behaviour. Unknowingly, or with intent, we play god. That play takes place on the world stage and threatens the viability of the global biosphere, and it takes place in living rooms and backyards whenever we make a choice about how we obtain our energy, water and daily bread. And however individual those choices may seem, we are inescapably social creatures so they are always the result of feelings shared and exchanged, the communing of minds and the dance of personalities.

We know from experience that the world is susceptible to our collective action and that action is grounded in community. It is there, for good or ill, that we make things happen. Semaphore may not be an ecological city, but like many small communities around the world, within its fractal essence, it bears the seeds that could grow one. But for those seeds to grow, there needs to be some effective planning at the neighbourhood scale.

“Neighborhood plans should contain a practical utopian vision for the neighborhood within the larger city, which is translated into medium-term policies and programs but also actions that can be taken on a short-term timeframe”, write Jayne Engle & Nik Luka. This doesn’t really exist in Semaphore. The closest it gets is local government planning and that happens at a level of scale which is outside that of the Semaphore fractal. There have been local business organisations that had some impact on creating events (the Semaphore Street Fair still runs annually) and there have been some attempts by small groups of interested locals to organise events to bring together and catalyse neighbourhood energy, notably through the auspices of Stuart Gifford’s café, but there is no effective organisation that can claim to be undertaking planning for the neighbourhood based on any kind of vision of what Semaphore might become. In this, Semaphore is not unusual, but to gird our loins for the battle with climate change and ecological instability that’s now rising on the horizon like a tsunami, every neighbourhood urban fractal needs to be planning for itself, working out how to turn its social energy into an effective force for positive change so that the patterns that make daily life functional, fun or fulfilling can continue.

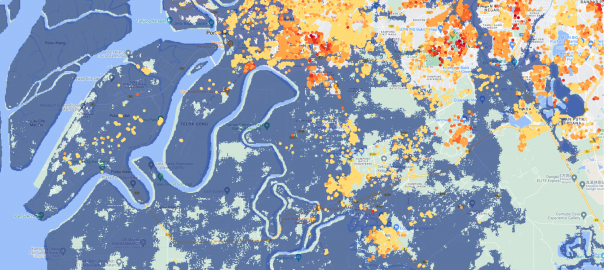

In the long term, to continue this thought experiment further—if Semaphore were to evolve into an ecocity urban fractal it would need to exhibit the characteristics of a fully-featured ecopolis [see my first blog and the box] in order to possess the resilience and autonomy required for surviving climate change and the 7 metres of sea level rise that would transform it into an island.

This is a work-in-progress.

Paul Downton

Adelaide

Leave a Reply