A wee garden in a windy city

From a leafy suburb in the shadow of Table Mountain, I need not venture far to encounter a myriad of remarkable creatures employing clever survival strategies. Fighting, stalking, feigning, loving, dancing, stealing, and darting, biodiversity spills into and out of my garden. It burrows beneath the lawn, slithers through the leaf litter, creeps up the drain pipes, hunts by the porch lights, and hides in my shoes.

Marvelling at Cape Town’s biodiversity through the lens of an ecologist is akin to gazing into the heavens through the telescope of an astronomer: equally humbling, spellbinding, and seductive. In my modest abode, there are not only remarkable species; there is a vibrant ecological community. It exists not in isolation, but as one tiny island in an archipelago of interconnected public and private greenspace, extending adjacent to the metaphorical mainland of Table Mountain National Park.

With a pair of binoculars, some old field guides, an iSpot account, an eco-literate girlfriend and a little patience, I have identified literally hundreds of species in my own backyard. Simply observing how they interact through the cycle of seasons, I have exacted immense pleasure.

The Scottish naturalist, John Muir, famously wrote:

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

Does this assertion hold true in cities? Can Nature’s long chains of ecological interaction persist in urban landscapes?

Picking out a single tree

Let’s return to my garden, or rather to my neighbour’s garden, where an old Wild Peach tree (Kiggelaria africana) towers over the partitioning wall. The Wild Peach is an indigenous evergreen species unrelated to the well-known fruit-producing Peach tree (Prunus persica). The early European settlers had a habit of naming indigenous South African trees after similar looking species known in Europe e.g. Cape Holly (Ilex mitis), Cape Beech (Rapanea melanophloeos), and African Red Alder (Cunonia capensis). Insofar as the garden is concerned, the Wild Peach tree is a pillar of the ecological community. Its summertime bounty of bell-shaped flowers may have enticed a queen Honeybee (Apis mellifera capensis) to establish her colony in a nearby abandoned car tyre, imparting wafts of sweet caramel into the air. The tree also brings music to the garden: its autumnal orange fruits are relished by the melodic Olive Thrush (Turdus olivaceus), slurring Cape Robin (Cossypha caffra) and chattering Cape White-eye (Zosterops virens).

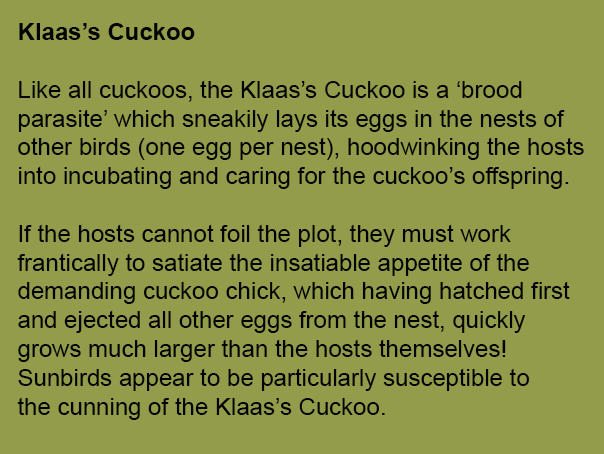

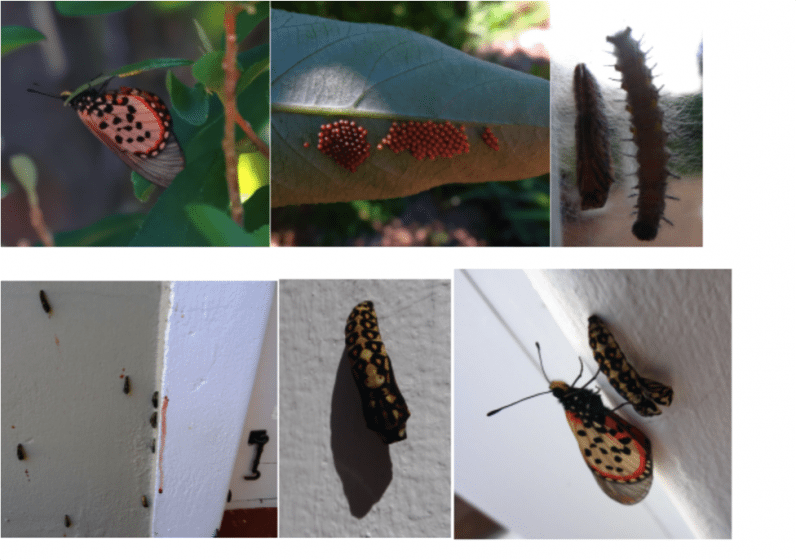

The leaves of the Wild Peach are toxic, but gleefully tolerated by one herbivorous species: the Garden Acraea (Acraea horta), a bright orange butterfly whose clutches of 40-150 tiny beige eggs and armies of black spiny caterpillars abound on the leaves all year round (see figure 4). The caterpillars feast voraciously, sometimes stripping the tree almost bare of foliage. By ingesting the Wild Peach’s poison, the caterpillars are themselves rendered toxic and thus unpalatable to would-be predators. However, certain cuckoos, like the Klaas’s Cuckoo (Chrysococcyx klaas), will visit the garden to gorge greedily on the Garden Acraea with seemingly negligible side-effects.

The caterpillars pass through several instars before abseiling off the Wild Peach tree on strands of silk. They disperse in droves, crawling across the flowerbed, lawn and patio, until they reach a suitable pupation site, whereat each caterpillar spins a silk mat before hardening into a chrysalis. The walls of my house are popular—at any given time, hundreds, if not thousands, of these pupae can be found fastened to the paintwork.

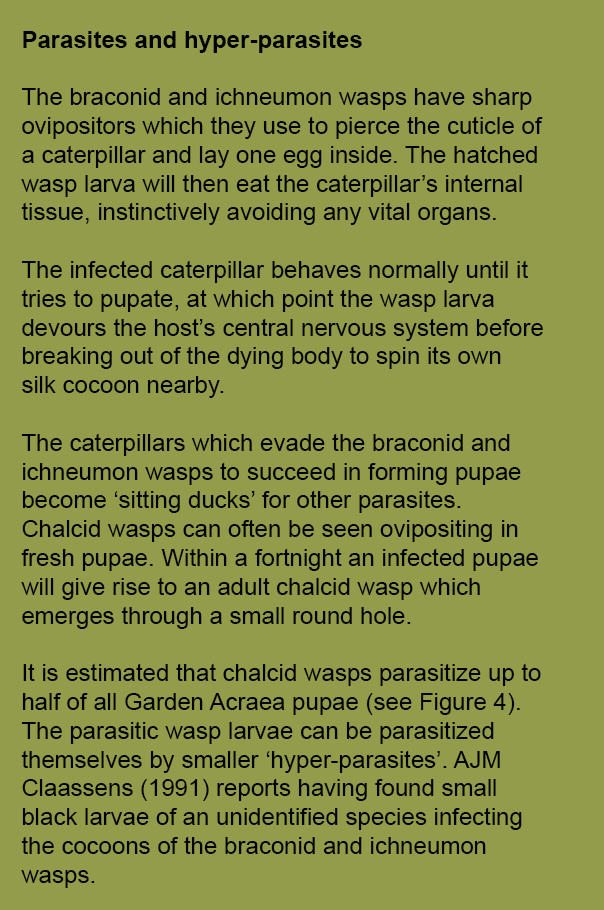

Besides the ravenous cuckoos, the Garden Acraea must contend with a range of deadly parasites, including braconid wasps (e.g. Apantales Acraea), ichneumon wasps (e.g. Charops spp.), chalcid wasps (e.g. Brachymeria kassallensis), bristle flies and fungus (see the Box below).

The metamorphosis from a caterpillar to a butterfly must be one of the most exquisite processes in the natural world. The small percentage of Garden Acraea to pass unscathed through the gauntlet of predation and parasitism emerge after a fortnight’s pupation as fully-formed adults. They warm themselves in sunshine before setting off, flying clumsily from flower to flower. If they can escape the cuckoos, they will mate and the females will lay eggs on the leaves of the Wild Peach tree, thus recommencing the life-cycle.

A fulcrum in a fragment

It seems that if I were to “pick out” the Wild Peach tree “by itself”, I would lose an awful lot of biodiversity that is currently “hitched” to it; from birds and butterflies to bees and bristle flies. I now look at the old tree with a renewed sense of appreciation. It is a fulcrum in a fragment of greenspace.

There could be many other species playing important roles in the garden’s ecological community. They could be linchpins in long chains of ecological interaction that I barely understand: the family of Cape Dwarf Chameleons (Bradypodion pumilum) which hunt small flying insects in the Blue Felicia Bush (Felicia amelloides); the scores of Egyptian Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) which come to feast on the berries of the Outeniqua Yellowwood (Afrocarpus falcatus); or the pollinating sunbirds which extract nectar from the tubular flowers of the Wild Dagga (Leonotis leonorus).

The example of the Wild Peach tree and the species hitched to it, suggests that:

- Indigenous trees can facilitate the establishment of vibrant ecological communities,

- Small private gardens can make substantial contributions to native biodiversity, and

- Long chains of ecological interaction can persist in urban landscapes.

Through the lens into the mirror

Looking into the mirror through the lens of an ecologist can be as uncomfortable as it is necessary. We might ask, what role do we play in the ecosystem and what is our net impact on Nature? Do we practice what we preach and persuade others to follow suit? Which aspects of our lifestyles need to change?

Contributors to The Nature of Cities have documented various ways to ameliorate our relationship with Nature. Their examples speak of the extraordinary power with which humans can enhance or degrade biodiversity. Clearly, like the Wild Peach tree, we too are part of ecological communities and may constitute links in long chains of ecological interaction. Knowingly or unknowingly, we interact with species both near and far, for better and for worse: the garden irrigation system confounds precipitation patterns and disfavours drought-adapted plants; the electric lights lure countless nocturnal insects to be preyed upon by Marbled Leaf-toed Geckos (Afrogecko porphyreus); the washing machine spews toxic grey water into precious wetlands situated 20 km away; the smooth morning coffee accelerates soil erosion half a continent away.

There is much that we can learn from the example of the old Wild Peach tree. It reminds us that no individual is an island unto itself and that even individuals can render positive and far-reaching ecological benefits. Like the tree, we too are “hitched” to the universe, and any pretension otherwise is delusional and dangerous.

Russell Galt

Cape Town

References:

- 1. Biodiversity Explorer www.biodiversityexplorer.org

- 2. iSpot www.ispotnature.org

Leave a Reply