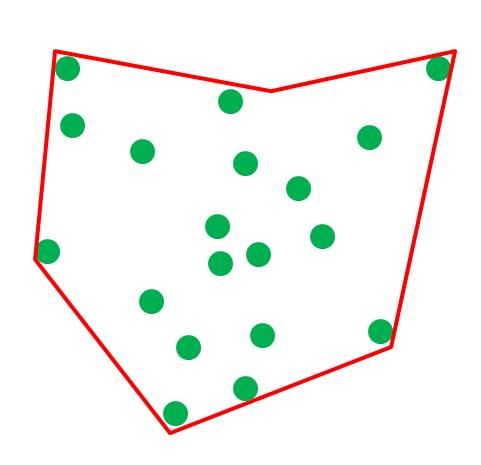

I like to simplify what constitutes urban nature in a given area. I therefore thought it might be interesting to provide an overview and to ask whether anything is missing, or erroneously included. This article expresses my view of the variety of forms that could be included under the “nature of cities” banner. On planning maps, nature is represented by polygons, lines, and points. Polygons are shapes, denoting area. Lines are linear features—though not necessarily straight ones. Points are individual features small enough not to require a shape to represent them.

Shapes

Cities fragment the landscape that they occupy. If that landscape was not already transformed by agriculture, the fragments may contain remnants of natural ecosystems. The sustainability of these relatively pristine ecosystems is dependent on their size, shape, and connectivity to one another, as well as the kind of pressures they experience from outside. In biodiversity hotspots such as the Cape Floristic Region in South Africa, every remnant is considered by conservationists to be a precious contribution to national and local targets to conserve representative samples as a percentage of original extent. Although these are the “purest” form of nature in cities, various studies, going back decades, suggest that they differ from their previous, un-fragmented state (see, for example, Andren 1994). Fragments may include wetlands, which are subject to the same pressures as other remnants as well as additional pollution and water extraction.

Coastal cities can count the strip of the coastal zone—both beaches and the sea—as part of the urban nature assets. Though often heavily utilized and over-fished, these zones are connected to distant ecosystems and, around the world, have features and even species in common. Often city governments are also responsible for managing them, while residents and tourists rely on them heavily for recreation—from swims at the beach to whale-watching.

Parks in cities can take a variety of forms but are typically mowed and manicured to some extent and, historically, little effort was made to naturalize them. Nowadays, many are breaking that mold. The Tiergarten in Berlin, for example, has sections that are allowed to grow wild, while others are manicured in the traditional way. Parks are for people and their nature will ultimately be determined by what the local populace prefers. With evolving ideas of the nature of cities we might see a future, therefore, in which the Tiergarten approach becomes more commonplace.

In the average city, gardens probably far exceed parks in total area. They are, however, intensely compartmentalized, limiting the flow of genes between them except for flying animals and the plants dispersed by them and the wind. It is also likely that gardens contain a far greater variety of species than parks in a given city, though many or most may be exotic species that do not perform the same functions as original and larger ecosystems. They can be remarkably diverse, as demonstrated in the famous example of 2,673 species of plants and animals recorded in Leicester garden over the course of 30 years (Owen 2010).

Botanical gardens merit separate mention because of the educational experience they offer over parks and the more expansive (and more expensive) experience of nature they offer over private gardens. Often paired with greenhouses, educational exhibits, and restaurants, they concentrate the experience of nature into a thoroughly-managed space while often maximizing biodiversity. Some, like Cape Town’s breathtaking Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, transition into natural vegetation. As one moves further into Kirstenbosch and away from the restaurants, the garden gets wilder while the crowds become more sparse.

Brownfield sites are the neglected cousins of the preceding categories. They have the added ignominy of an uncertain or terminal future, with many being earmarked for future development. Studies have shown, however, that they play a role in supporting biodiversity and even in providing a natural experience (Bonthoux et al. 2014). Importantly in the context of urban nature, a perceived value (often based on the presence of a single, iconic-enough species such as a breeding pair of birds) may be motivation enough for enhancing such sites or retaining a portion when they are developed, for the sake of nature.

Lines

A variety of green infrastructure can fulfill the purpose of a natural green corridor. In systematic biodiversity planning, however, corridors are considered to be strips of natural vegetation and the ecosystems they support, which connect more substantial fragments of natural vegetation. Their effectiveness depends on their length and breadth, and the species that need to use them to traverse the urban matrix, and entire books have been written on the questions of how they should look in terms of width, length and quality (see for example Hilty J and Lidicker WZ. 2006).

Avenues of trees or shrubs along roads are, in some ways, the linear equivalents of parks. They are, however, typically less diverse and imaginative, despite offering an undeniable improvement on a treeless road. Singapore is a world leader in re-thinking the concept of an avenue. In this crowded city, where space is paramount, biodiversity authorities have responded accordingly by planting multi-species, multi-layer “avenues” that contribute to the biodiversity of the city as much as to its aesthetics.

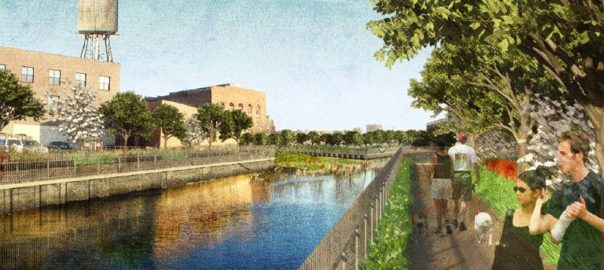

“Water lines” in cities range from relatively sterile concrete canals that carry only water, to rivers with a variety of plant and animal life and vegetated banks. The former is often a wasted opportunity to bring nature to the city, although it may be necessary where space is severely limited. The ecosystem services provided by naturalized water lines, such as flood attenuation, water purification and recreation may, however, surpass the benefits of a canal even in economic terms. Perhaps the most popular option is a compromise between these two ends of the spectrum. In Seoul, the Cheonggyecheon Stream—re-engineered after the demolition of a highway —attracts thousands of visitors but is expensive to maintain because water needs to be piped in from elsewhere. Retrofitting often tends to be expensive—a reminder of the importance of design in early-stage city planning.

Points

Many members of the public don’t think of any of the shapes and lines discussed above when considering nature in cities—they think of wild animals. Many “cosmopolitan”, or widespread, species play a role in various parts of the world. Some are appreciated by the public (squirrels, ducks), others abhorred (rats, cockroaches), and still others produce mixed feelings (pigeons, seagulls). Many such species have little value in terms of biodiversity due to their ubiquity and uniformity; nevertheless, they are nature, and must be counted as residents of cities. One common phenomenon regarding urban wildlife is that the rarer the species is, the more it is valued. This is demonstrated, for example, by the excited reaction of tourists having their first experience of a species that may be common and problematic in a city they are visiting for the first time, such as foxes, raccoons or mallard ducks. Animals in the city are usually mapped (i.e. treated as points) only if they are relatively rare.

Plants constitute many of the features discussed under shapes and lines, but in the urban context, or the context of the planner, they can also be points. This is especially true for large and iconic trees (see also Trees as Starting Points for Journeys of Learning About Local History and Heritage Trees of Cape Town (Continued) by Russell Galt), which may be located in a concrete matrix, as well as individuals of rare species in parks or gardens. Individual trees may have great natural and cultural relevance. In the seaside town of Mossel Bay, in South Africa, for example, the “post office tree” is an ancient milkwood (Sideroxylon inerme) and a national monument that acted as a mail system for sailors in the 1500s, who hung their shoes with notes in them for safe delivery.

Others

It’s not always so clear whether a feature should be regarded as point, line or polygon. For example, a cluster of points can constitute a shape. A population of sedentary organisms (i.e. mostly plants), especially a rare species, may therefore be represented by a polygon of the area in which they are distributed, rather than by individual points.

Green roofs and, to a greater extent, green walls, are difficult to categorize in the spatial sense but are also important contributions to urban nature.

As we get further into more-difficult-to-define features, we should not forget the “sandwich spaces” discussed by Timon McPhearson and Victoria Marshall—the spaces between buildings, rooftops, walls, curbs, sidewalk cracks, and other small-scale urban spaces that exist in the fissures between linear infrastructure (e.g. roads, bridges, tunnels, rail lines) and our three dimensional gridded cities. These spaces can be reservoirs for species, assist with water infiltration and offer other benefits discussed in McPherson and Marshall’s piece.

Lastly, in cities, representations of nature are to be found in the intensively managed and artificial confines of zoos, aquariums, and museums. If urban nature is to be defined as that which provides us with an approximation of a natural experience, and if it contributes to the conservation of biodiversity, these cannot be excluded. Especially if education and awareness are our goals, these features need to be considered a part of the nature of cities.

Concluding remarks

This was a brief blow-by-blow summary of urban nature in categories, as seen through the eyes of a conservation biologist. The tools that are used to map and appoint attributes to these features, to indicate their location and importance, is often a geographic information systems (GIS)—a digital mapping device. We all use the resulting maps to get around cities with which we are not familiar, while city administrations increasingly focus on a network of green spaces as a key component of conserving biodiversity in the urban environment. For these reasons a holistic, spatial view of the nature of cities will always be an important contribution to our understanding and conservation of the nature of cities.

Andre Mader

Montreal

References

Andren H. 1994. Effects of habitat fragmentation on birds and mammals in landscapes with different proportions of suitable habitat: a review. Oikos. 71:355-366.

Bonthoux S, Brun M, Di Pietro F, Greulich S, Bouché-Pillon S. 2014. How can wastelands promote biodiversity in cities? A review. Landscape and Urban Planning. 132: 79-88.

Hilty J and Lidicker WZ. 2006. Corridor Ecology: The Science and Practice of Linking Landscapes for Biodiversity Conservation.

Owen J. 2010. Wildlife of a Garden—a thirty year study. Royal Horticultural Society.

Leave a Reply