I believe that urban landscape matters! The landscape in which one grows up, matures, and lives life may be the essential factor in determining the behavior towards and empathy with nature and with other people and their cultures. The landscape can even be the way we connect to ourselves.

The shape of our cities is a result of the historical changes in land cover, built structures, and the continuous man-made interferences that are made in the landscape and its relationship with natural factors such as geomorphology, climate, biodiversity, ecosystem remnants, green areas, and urban forests. Social aspects are not less important. Cities that segregate social life in closed communities (being gated high-end or middle class enclosures, or favelas), malls and cars, may induce prejudice and injustice. Live streets and urban amenities are the public realm where the different meet, learn with each other, and may have daily contact with nature and natural processes.

Landscapes and the spiritual bond with Nature

When I walked along the Philosopher’s Path in Kyoto, I felt the spiritual power of Nature in the urban landscape. The path meanders along a channelized river, with clean waters in the city border. The landscape is peaceful, with the city in one side and the forest in the other, the water flows in between.

There are several Temples and Shrines along the path. The Shinto Shrines profoundly touched me. I was ignorant of their sacred meanings, but I have never felt this deep connection with Nature in a spiritual way before. Being a non-religious Jew myself, I perceived the temples and churches I have entered in my life as built structures; I have never had the feelings I had in the shrines! Actually, much earlier in my life I remember when I was in Assisi (Italy), I felt something very special. I was touched by St. Francis of Assisi’s history of loving of nature and its creatures. At the top of the hill was the place where he had lived, and I could feel the energy of nature flowing around. Maybe this was the source of his inspiration and connection with holy love to nature and living organisms.

After these experiences, I started reflecting about our divine bond with nature, and how the landscape influences our lives and values.

Until I read the E.O. Wilson’s book The Creation, I had never really had any thoughts about how religion could play an important role in ecological education and awareness raising. In his book, scientist Wilson dialogues with religion, and looks for the common ground to protect and restore Nature.

And what a grateful surprise was the Encyclical Letter of Pope Francis! The LAUDATO SI’ calls on all of humanity “to care for our common home”. Firmly grounded in science, the Pope talks about consumption, greed and accumulation; the oil addicted society that eradicates ecosystems and depletes natural resources. He also says that we cannot trust only in technical solutions to solve our environmental and social problems. He declares the urgent need to restore, conserve, and protect our environment. He urges all of us to mitigate the colossal damage that our civilization has made, and to avoid climate change and the huge uncertainties that are threatening the future of humanity. The response to his message has been massive, and I believe that 2015 is crucial to prioritize life and also to shift the way we see, plan, and design our landscapes at all scales.

Cities in challenging times

How can globalized, modernist urban landscapes reconnect urban dwellers with Mother Earth?

We are living in challenging times in which cities play a crucial role, as so many authors of The Nature of Cities have pointed out from different perspectives. In this international blog, contributors have presented and discussed examples that are popping up around the world—of social-ecological oriented research, planning, and design, wherein biodiversity is treated as fundamental. Many of those case studies come from local residents who want more livable places to raise kids in healthy and diverse environments.

However, many cities have remained in the old modernist sprawl paradigm—based on high consumption economies, gated communities with homogenized gardens, and automotive transportation that requires costly infrastructure—known as business-as-usual. The surrounding ecosystems’ remnants and productive lands are eradicated in this process. Also, old urban areas have been transformed, destroying their history and culture. Gentrification in renovated regions is another negative factor, displacing residents and small businesses while ceding room for a globalized culture and international brand stores. This globalized trend widens the social gap even farther, especially in poorer countries, where it is already abyssal.

Our planet is urban not only because the Biosphere is giving way to built surfaces, but also because the political and economic decisions are largely taken by city dwellers.

I consider ecological illiteracy to be one of the main drivers of the disconnection and disregard of our Home: our planet, our region, our city, our neighborhood, our street or our own home. Or even with our own selves!

How can people connect with nature and its processes if they spend their life in air-conditioned (or heated) built boxes, apart from biodiversity and social diversity? How can they develop and act on their Biophilia in artificially built and “controlled” landscapes? [Biophilia is the “innate and genetically determined affinity of human beings with the natural world” (E.O. Wilson)] Much has been written, published, and discussed in conferences about those issues (see for instance Tim Beatley in this blog).

Urban landscapes and reconnection with Nature

For me, the Pope’s call to “care for our home” is more than a metaphor for the Planet’s degradation and the related risks to Humanity. It is time to care for our home at all scales, including the ecological restoration of our urban landscapes.

In Brazil, the number of urban dwellers that are engaging in growing organic food, fighting for ecosystem restoration and water conservation, and getting together to learn and exchange experiences has been growing exponentially. As everywhere, in this country, social media is helping people to communicate among themselves about their findings and experiences with Nature and natural processes in multiple ways. We have very positive results on the fields that actually enhance urban landscapes ecologically and socially: publications and courses on related themes are starting to pop up around the country; leaders are assuming important roles, participating in actions and policy elaboration; volunteers are expanding their work in a society without a tradition of social work.

There are lots of good examples that are more powerful every day, as I have already mentioned in my previous posts in this blog. Hortelões Urbanos (Urban Food Gardeners), an urban agriculture group in São Paulo, has been a source of knowledge and inspiration to similar projects in cities around the country, and now depends on more than 17,000 followers (in less than 4 years). Their interventions in parks and squares in São Paulo, the largest Metropolitan Region, are awesome: from green or gray deserts, they create biodiverse, productive landscapes with waters springing again.

Rios e Ruas (Rivers and Streets) is another group that has been working in the last decades to ecologically educate residents. They have been tracing rivers and creeks that were wiped out from the landscape. The severe drought that is hitting Southeastern Brazil, with water shortages threatening the removal of large number of residents from urbanized areas, has helped to give visibility to their work

A few years ago Juliana Gatti and Sandro Von Matter started the Instituto Árvores Vivas (Living Trees Institute). They have a remarkable engaging and educational role in São Paulo. They are actually changing the way Paulistas (São Paulo residents) see, feel, and act regarding trees and their urban lives.

A few years ago Juliana Gatti and Sandro Von Matter started the Instituto Árvores Vivas (Living Trees Institute). They have a remarkable engaging and educational role in São Paulo. They are actually changing the way Paulistas (São Paulo residents) see, feel, and act regarding trees and their urban lives.

The green economy is slowly starting to emerge in Brazilian cities, with new companies that develop green technologies to implement green roofs and walls, solar energy, water bioremediation and conservation, and bio-sanitation, at different scales. Hopefully, with the dramatic water shortage and the challenges of the changing paradigm towards a clean economy, they will rise and help Brazil get out of its severe economic crisis.

Another excellent and inspirational example is the Skygarden, a relatively new company specialized in green roofs and walls, that mimics São Paulo’s native ecosystems: Mata Atlântica (Atlantic Rainforest) and Cerrado (Brazilian Savanah). The founder/owner Ricardo Cardim, studied odontology, but soon fell in love with botany and native ecosystems and then went on to a Master’s in biology. In 2008, he started an NGO named Árvores de São Paulo (São Paulo Trees), and from then on has been helping to change hearts and minds regarding autochthonous urban trees, not only in streets and parks, but also in roofs and facades

In Rio de Janeiro, the remarkable TransCarioca Trail project is underway with the support of hundreds of volunteers under the leadership of Pedro Menezes and Celso Junius. It is a more than 180 km-long walking track over the splendid massifs of the city, connecting several protected areas. It spans the world-renowned Sugar Loaf to the distant beaches of Guaratiba.

Another initiative that is also gaining more support is Green Corridors, part of the Carioca Mosaic project, in the lower areas on the water basin where most of the Olympic Games facilities are concentrated.

Shift for a better future

I have written before in this blog about the challenges and opportunities that the city of Rio de Janeiro has had in the last few years, especially with the high investments focused on international events—the 2014 Soccer World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games being the most internationally recognized. Unfortunately, decisions about the future of our cities (not only Rio de Janeiro) are mainly focusing on companies that build gray infrastructure, engage in non-productive land speculation, and support the oil-based transportation industry. This means building cities-as-usual: sprawling and transforming the landscape and changing natural processes and flows with social segregation.

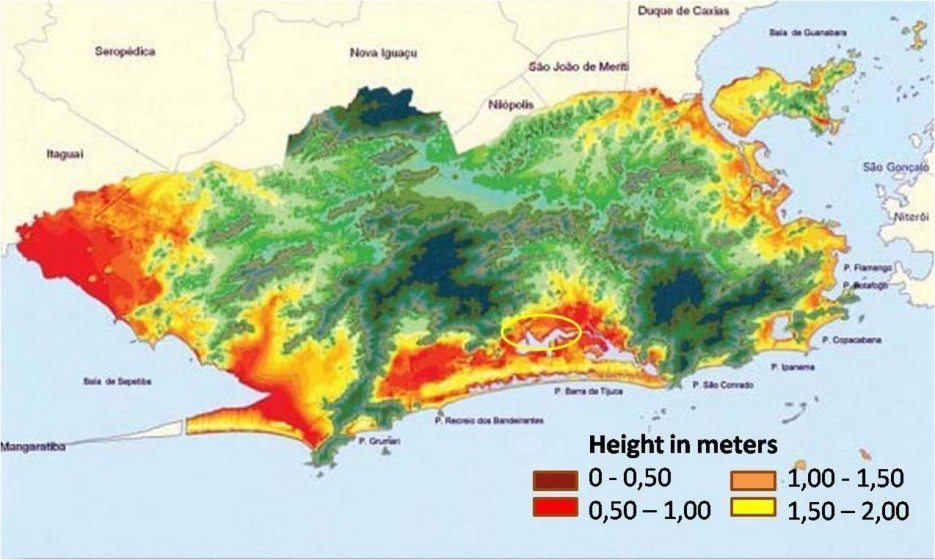

The current trend can be easily seen in the “Marvelous City” of Rio de Janeiro. There is a disconnection between the recommendations of scientific assessments to adapt the city to climate change and what is being actually implemented. The money is flowing to the West Zone, where the map shows high vulnerabilities of low lands to floods and sea level rise.

We might expect that what is happening was planned based on the knowledge that was generated by state-of-the-art academic research, supported by the city since 2007. Not at all…Wetlands and protected areas have been eradicated with the excuse of the Olympic Games. The rich biodiversity and wet landscapes that offer irreplaceable ecosystem services have been transformed into more and more gated communities, commercial areas adorned with homogenized cosmetic gardens, and the expressways on which oil-dependent transportation oil-dependent relies. In this process, the city is losing not only its ecological heritage, but its cultural identity.

One of the most significant examples is the Olympic Golf course that was built over one of the last protected remnants of Restinga (sandy soil, sea border ecosystem). Besides the elimination of biodiversity and ecosystem services, the landscape conversion to lawn requires daily irrigation in times of uncertain climate. The real estate market is the beneficiary of this mega-gated development, as many others in the same water catchment.

The social segregation and lack of sanitation are still huge issues and the City has not complied with the commitments it assumed when the right to host the Olympic Games was won. The rivers, lagoons and even Guanabara Bay are heavily polluted with sewage, diffuse stormwater run-off, and garbage.

Civil society is fighting against what is happening in the city. Its voices are heard mainly on social media when the traditional media doesn’t open space for protests and meetings.

Landscape for today and the future

Landscape is becoming an important issue as people start to understand how they depend on biodiversity and the ecosystem services they need to live healthy and fulfilling lives. Unfortunately, in Brazil, the profession of landscape architect is neither recognized nor institutionalized. We are in the process of passing a law that will make possible to start new undergrad courses in the area of landscape architecture in Brazilian Universities. We need to implement interdisciplinary courses, establish research groups, and fund pilot projects that demonstrate how our landscapes work, their social-ecological functions, and their processes.

Pierre-André Martin and I are coordinating a new Master’s in Ecological Landscape Planning and Design at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro in the Department of Architecture and Urbanism, to start next August. The course is interdisciplinary, with professors from landscape planning and design, urbanism, biology, geography, social sciences, law, anthropology, and engineering.

We urgently need cities that praise nature, that protect and restore native biodiversity in all possible ways. We must escape from the trap of fragmented knowledge and look for integrative research and teamwork on adaptive landscape-based urban planning and design. We must monitor results and learn what works or not in our landscapes. We must plant trees to have water and food. The cities have to be part of the Biosphere with green infrastructure that regenerates degraded gray and polluted areas. People have to be educated and reconnected to life to participate in the landscape planning and design process.

I hope that the momentum we are living is transformational. Powerful forces are moving to make effective change in the economic, social, and environmental paradigms: from a competitive society to a more cooperative world, where natural capital has more value than the virtual financial market. I believe that the call of Pope Francis can help, especially in Brazil. We are the most populous Catholic country in the world, with more than 120 millions followers of the religion.

I hope all people hear his call and give science and practitioners with ecological vision the opportunity to contribute to a shift to a better future.

Cecilia Herzog

Rio de Janeiro

Leave a Reply