A review of Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action for Long-term Change, by Anthony Garcia and Mike Lydon. 2015. ISBN 9781610915267. Island Press, Washington. 256 pages.

Tactical Urbanism: it’s one of the buzz words in the emerging people-centred planning paradigm. If you do a Google News search of the term, you’ll find articles from all the news sites beloved by urbanists: Next City Daily, CityLab, Slate, ArchDaily, et al. Often used in the context of citizen-led improvements to the urban environment, it can mean everything from small beautification projects to major city-led revitalization efforts. To me, it evokes images of renegade city-dwellers armed with spray paint, bollards, and patio furniture, taking urban planning matters into their own hands to improve their small piece of the city. But Tactical Urbanism can mean a lot of things: there is no unified definition to place it into the larger dialogue about citizen action in urban planning.

These many meanings are captured in Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action for Long-term Change, a book by American urban planners Anthony Garcia and Mike Lydon, both leaders in civic advocacy and principals of The Street Plans Collaborative. By clearly laying out what tactical urbanism is—the authors define it simply as an approach to neighbourhood building and activation using short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions and policies (in other words, according to Professor Nabeel Hamdi, Tactical Urbanism is “making plans without the usual preponderance of planning”)—the groundwork is laid to build on this theory of change by providing successful examples and providing guidance for making it work in practice.

These many meanings are captured in Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action for Long-term Change, a book by American urban planners Anthony Garcia and Mike Lydon, both leaders in civic advocacy and principals of The Street Plans Collaborative. By clearly laying out what tactical urbanism is—the authors define it simply as an approach to neighbourhood building and activation using short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions and policies (in other words, according to Professor Nabeel Hamdi, Tactical Urbanism is “making plans without the usual preponderance of planning”)—the groundwork is laid to build on this theory of change by providing successful examples and providing guidance for making it work in practice.

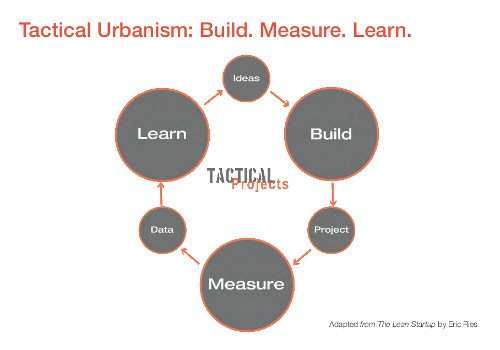

I found it to be an accessible read, heavy on place-based examples, personal narratives, and photographs, while touching on planning and public space theory. As a person who studied urban planning and is most interested in working in the community sector, I found this book to effectively bridge the worlds of quick and visible on-the-ground action with less exciting but very rigorous long-term planning that sets out comprehensive frameworks for development. It also does a great job of celebrating the many successes of citizen-led action, while acknowledging an integral part of the iterative “build-measure-learn” cycle of tactical urbanism: having the courage to fail.

I found the tone to strike a positive yet pragmatic balance: it has a “you can do it” inspirational voice, but includes frank discussion of the bureaucratic obstacles that continue to prevent the kinds of straightforward, low-cost interventions championed in the text. This left me with the impression that it is possible to create lasting change in one’s community—but don’t expect it to be smooth sailing. A note on terminology: while this book uses minimal planning jargon, the term tactical urbanism itself may not resonate widely in its attempts to capture a movement that presents an alternative to the long-range municipal planning processes that shape our cities. An alternative term used by New York’s Project for Public Spaces is “lighter, quicker, cheaper”. Jaime Lerner’s term “urban acupuncture” also seems to have leverage with a non-planning audience, although it refers specifically to pinpointing vulnerable areas and then using design to re-energize them. “Trial-and-error urbanism” might also capture Garcia and Lydon’s framework: rather than spending a lot of time, money, and resources on coming up with the best plan, we would do better to test things out on a small scale to see if there is potential for wider applicability and sanctioned change.

I found the weaving through of examples that illustrate how we shape our cities by doing something in the short-term, with the view of changing conditions for the long-term, to be immensely helpful in understanding the strategic nature of tactical urbanism. While any intervention that alters the urban landscape, such as yarn bombing a chain-link fence or adding life to an underpass with graffiti or paste-ups, can change people’s perceptions of a space, what makes tactical urbanism tactical is its efforts to shift thinking and patterns of development by demonstrating what is possible with a little creativity and often a whole lot of DIY smarts.

Throughout the book, Lydon and Garcia highlight examples in which an unsanctioned project was eventually supported by government—often a city’s planning or public works agency. This gradual shift from unsanctioned to sanctioned can ease some of the burden of project maintenance on volunteers while allowing cities to take leadership on facilitating bottom-up planning. However, the authors embrace the idea of having a spectrum of projects, from those steeped in DIY culture all the way to “tactical economies”, such as setting up pop-up businesses to attract private investment in a stagnant area. Not all tactical urbanism efforts will be okayed by government, and that should not necessarily be the end goal of citizens looking to test out urban interventions.

This dance between citizen-led action and long-term policy change was a motif throughout the book, and one that I think has potential to provoke conversations about shifting public participation in planning from “show-and-tell” to deep collaboration. It was incredible to read about such a range of stories about projects that began as one-off, localized efforts but have now been scaled up or out by budging municipal policies. For example, on a recent visit to Portland, OR, I noticed that neighbourhood intersections were often adorned with murals.

Turns out, this is thanks to a crew of Portlanders who, concerned about road safety in their neighbourhoods, obtained a block party permit to undertake “intersection repair”: painting a mural across the intersection, adding a tea station, community bulletin board, and more. Despite initially meeting resistance from the Portland Bureau of Transportation, the group persisted, demonstrating improvements to quality of life through resident surveys. Eventually, the City saw the light: facing a decrease in funding for art and public spaces, yet needing to fulfill livability and sustainability policies, they eventually adopted an Intersection Repair Ordinance. Examples like this show what is possible when residents pave (or unpave!) the way for city-level policies that enable more efficient and people-friendly planning.

For those who already have a tactical urbanism idea in mind, the book makes effective use of basic diagrams to explain the practice: one in particular that budding tactical urbanists might want to consult is the Tactical Spectrum, showing the range of projects from unsanctioned to sanctioned. In this context, unsanctioned refers to projects that citizens can go ahead and do without any government support; sanctioned describes projects that require support and approval from government, usually city departments, by nature of their scale or complexity.

While budgeting, permit application, and other logistical matters aren’t the most exciting parts of planning your tactical urban intervention, it is helpful to think about how much government support you will need so you don’t find yourself facing unforeseen obstacles.

Overall, though, the authors stress that no matter the nature, scale, and degree of government implication in the project, the most important consideration is how it will affect the community. This is something that I find often goes missing in conversation about urban revitalization: who is doing the revitalizing, for whom, and to what ends? In the second-to-last chapter, “A Tactical Urbanism How-To”, the authors present a series of questions that one needs to ponder before getting a project underway, from sourcing materials, to leveraging community support, to maintenance. I liked the emphasis on thinking through what the effects might be on the surrounding communities: it is easy to forget that what you think is a swell idea might not actually be what a particular group of people needs or wants.

This concern for ensuring that tactical urbanists do not end up adversely affecting the communities they are trying to improve gets to the crux of whether planning should come from the grassroots or “grasstops”. While tactical urbanism can bring alternative methods and accelerated timelines to municipal decision-makers’ attention, ultimately their goals are not so different than those espoused by planning policy: what city’s Official Plan doesn’t use words such as sustainable, vibrant, and resilient? One aspect of tactical urbanism that merits more exploring is what happens when the landscape of projects starts to become saturated. As with anything, the more people involved, the greater the need becomes for checks and balances. Does this kind of “lighter, quicker, cheaper” intervention only work when few people are doing it? How can multiple groups with competing visions negotiate the space of tactical urbanism without undermining each other’s’ efforts—and the visions, guidelines, and plans laid out by city government?

While these big questions aren’t answered in this book, the authors do suggest, through examples of informal partnerships between citizen groups and city government, the possibility of a new planning practice. This practice derives rigour from harnessing residents’ skills, energy, and imaginative foresight to balance comprehensive, long-term planning with the kind of quick-win, prototyping work that can get folks excited about improving the places they live. To refer back to Portland, the City’s Office of Neighbourhood Involvement coordinates a 95 neighbourhood-strong network of district coalitions and offices which provide support and technical assistance to volunteer-based neighborhood associations, community groups and individual citizen-activists. It may be in this type of supportive partnership that the strengths of both tactical urbanism and bureaucrat-led planning can be leveraged to build communities that are both functional and personable.

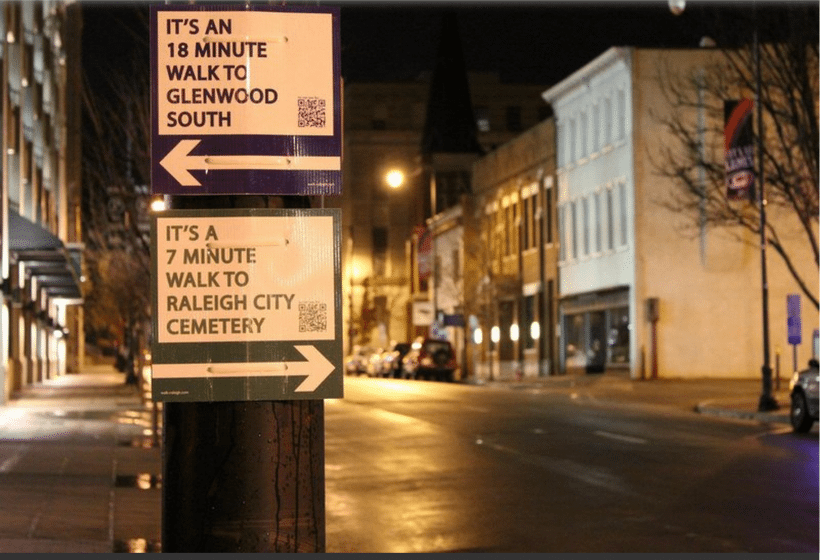

Until that happens, though, people will continue to find ways to mobilize and to shape the places they care about. It may sound cheesy, but seeing photos showing regular people doing work in their communities, wearing normal clothes, and using simple methods, reinforces the authors’ emphasis that truly, anyone can do tactical urbanism. It’s hard not to be inspired by the go-getters described in this book: from Baltimore resident Lou Catelli, who painted a crosswalk at a dangerous intersection when city staff failed to do the job, to Matt Tomasulo who created simple wayfinding signs to encourage people to actively rediscover their city.

In particular, understanding how to exploit loopholes in the web of planning regulations is a great skill to have in one’s pocket: from feeding the meter to roll out a temporary park in a parking space, to using a catch-all special events permit for “build a better block” programming, there are a surprising number of instances in which seemingly hard-and-fast rules can be reinterpreted, at least in the short term. Another takeaway message that seems obvious but may be underappreciated is the value of developing allies in city staff by getting them on board early in the process by documenting successes, including community buy-in. If staff perceive value in what you’re doing, they’re that much more likely to put pressure in their departments to make the big policy changes that can facilitate and even mandate what you’re championing.

Throughout the book, the authors encourage the reader to reconsider in-between spaces that often do not fit into traditional land-use planning. One shining example is an Orlando community group’s efforts to activate a strip mall parking lot by setting up a temporary night market: the Audubon Park Community Market. The market was so successful—thanks to buy-in from residents and nearby business owners—that the organizers have now opened a brick-and-mortar market two blocks away. This probably would not have been possible had they not demonstrated the demand for and benefits of a temporary community market. If a group of engaged residents can transform one of the least people-friendly places—the surface parking lot—into two thriving markets, I’d say we have a lot to be excited about for the future of city-building.

While it is the individual stories of citizen-led action that bring the book to life, the authors also provide context to these stories by tracing the evolution of five broad categories of tactical urbanism: Intersection Repair, Guerilla Wayfinding, Build a Better Block, Parkmaking, and Pavements to Plazas. These in-depth explorations trace the origins of each approach while sharing resources that readers can draw from along the way. For example, understanding the genesis of now-iconic programs such as New York City’s Pavements to Plazas (see: Times Square, Park Ave, and many more) highlights how far the idea of people-centric planning has come in a short time period—and what we can look forward to as these ideas become championed by municipal leaders such as the formidable Janette Sadik-Khan (check out her TEDTalk: NYC’s Streets Are No So Mean Anymore). One aspect of the book that folks with great ideas but limited resources will appreciate is that often the best interventions are simple, and start on a small scale. Daniel Burnham famously proclaimed “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood…”; rather, Lydon and Garcia posit that it is by testing new approaches in small ways that we create the kind of bigger shifts we’re yearning for in cities.

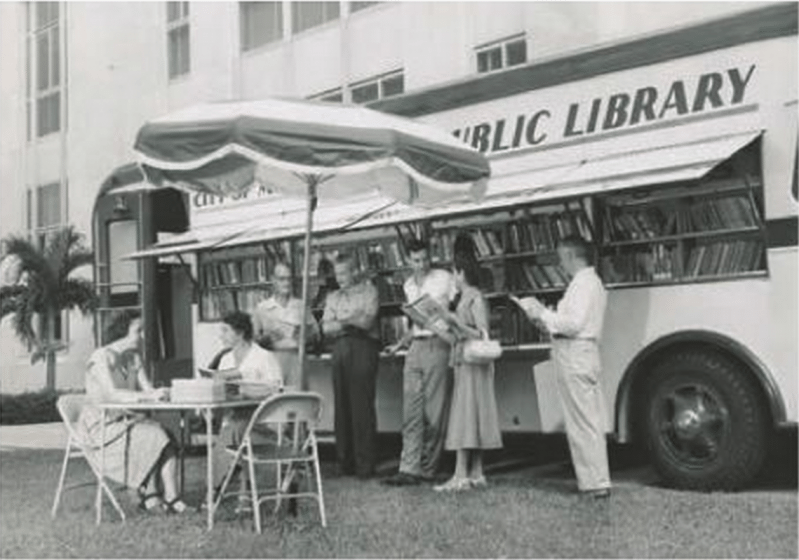

In addition to contextualizing tactical urbanism as a whole, the book brings in a bit of history: while the term is new to the city-building lexicon, the concept dates back more than a century, when city dwellers faced many of the same concerns that pervade discussions about cities today. For example, I didn’t know that Open Streets (championed in Canada by organizations like 8-80 Cities) can be traced back to Safe Streets for Play movements in New York in the early 1900s. It is inspiring to witness the progression of this simple idea—turning streets from car-centric transportation corridors to paved parks for all—that is now being embraced by diverse communities (see: Bogota’s Ciclovía, LA’s CicLAvia, Austin’s Viva Streets, Ottawa’s Sunday Bikedays, and many more). It’s a prime example of tactical urbanism because it starts with a simple action: replacing spaces for cars with spaces for people—and over time has become embraced by municipal planners (although perhaps not yet traffic engineers). Other fun historical tidbits: the bouquinistes along Paris’ Seine as early examples of unsanctioned commerce; Sears’ pre-fab, mail order houses as a basis for today’s shipping container architecture; bookmobiles as informing mobile services before city infrastructure is put in place

I would recommend this book to both world-weary city planners seeking to be re-inspired to improve public spaces and the next generation of municipal “intrapreneurs” who are driven to catalyze big changes—as well as folks working on the ground in their communities seeking guidance on strategic and logistical matters. While many of the examples may be familiar to anyone interested in urbanism, I certainly found a few new ideas that sparked further research. Plus, the “how-to” parts of the book ensure that you’re not trying to reinvent the wheel: the wonderful thing about tactical urbanism is that it’s open-source by nature, so learning from others’ successes and drawbacks is part of the process.

If you don’t have time to read the whole book, I would recommend spending an hour with the last two chapters. I guarantee you’ll come out with a practical idea or two on improving your own neighbourhood through tactical urbanism—while avoiding getting caught behind a wall of red tape.

Sarah Bradley

Montreal

Postscript: Are you keen to get you own tactical urbanism project a try? 100in1 Day is a good way to get started. It’s a global festival of civic engagement, designed to embrace our power as urban citizens by spending one day of the year testing out small urban interventions to ultimately improve one’s city. These can range from activities, to education, to installations that temporarily change the built environment. In 2015, 100in1 Day happened on June 6 in four Canadian cities. Check out the 100+ urban interventions that happened in Halifax (Nova Scotia), Hamilton (Ontario), Toronto (Ontario), and Vancouver (British Columbia).

Cities for People also hosted a webinar on 100in1 Day and Active Citizenship featuring Juan Carlos Londono and Cédric Jamet, two Montrealers who launched the 100in1Day movement in Canada. You can watch it here.

2 Comments

Join our conversation