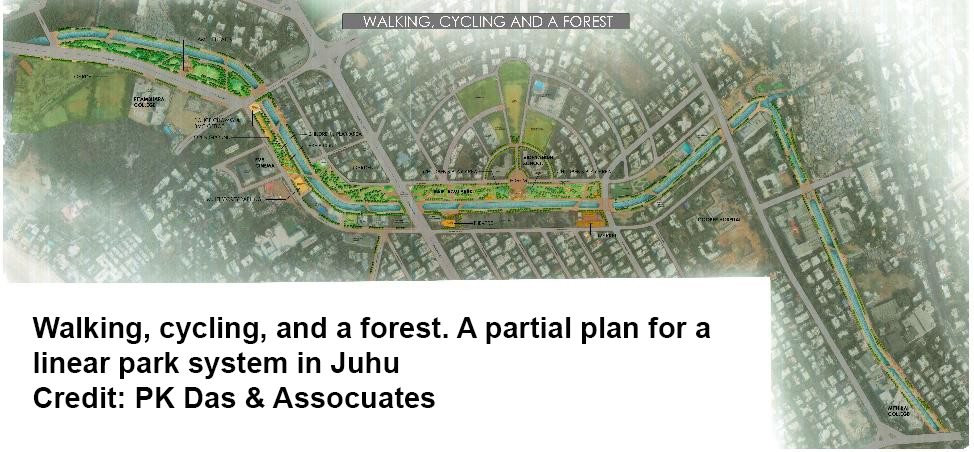

Can we re-envision our cities with a stream of linear open spaces, defining a new geography of cities? Can we break away from large, monolithic spaces and geometric structures into fluid open spaces, meandering, modulating and negotiating varying city terrains, as rivers and watercourses do? This way, the new structure of open spaces would relate to and integrate with many more areas and provide access to more people across neighborhoods and the city. Why? Because a linear park passes near more people than a square part of the same size—that is, more people are within a short walk of a linear park than a square one of the same size in the same neighborhood. And linear parks are parks of opportunity. Where would one create a big square park in Mumbai? But streams and other naturally linear features provide opportunities to create park access in an otherwise crowded urban zone.

Over the years, across cities, we have been planning and building parks and gardens and other public spaces as geometric blocks that, in most instances, stand out in sharp contrast to the character of the neighborhoods in which they are placed. Such decisions that impose such blocky parcels of land seem guided by intentions of promoting exclusive spaces, spaces that could be contained and controlled, with access to them regulated. In many urban situations, such blocks have led to class and community polarization due to the very nature of their design and governance structure. A public space has significant socio- political colour that cannot be ignored or masked under the guises of city beautification programs and limited environmental objectives.

Today, we are confronted by many critical questions that need to be answered. Can public spaces in various forms be conceived to harness social and community relationships? Can they bring together the disparate fragments of spaces within cities, otherwise characterized by forced ghettoisation and gated communities? Can sensitive ecological assets that have been classified, colonized, and/or treated as backyards of development programs be put into the public domain and turned into social and cultural fore-courts? How can we alter the established blocks of barricaded spaces and structures into open and clear spaces for all, forever? Can more people freely access and exercise control over common property in order to democratise the ecology of cities? Alternately, can we work towards developing linear structures of open spaces as an answer to many of the above issues, while significantly altering the established, dogmatic order of public spaces in the planning and development of cities?

These are key questions for the future of city building. It may be a tall order, but worth pursuing, as it is rooted in the idea of a new urban rights agenda—governance models that strive to achieve integration, equality, and socio-environmental justice. In most instances, public spaces have been shrinking with city expansion. Open land, including that reserved for gardens and playgrounds, has either been converted by governments for building construction purposes or is being grabbed and developed for real estate projects, as has been experienced in the case of Mumbai. In such an event, collective or community ownership of common spaces becomes crucial for maintaining a desirable balance between open spaces and built-up areas. It is in this regard that linear streams of open spaces achieve significance. This is not to say that larger parcels of land for open spaces are not necessary at all. Rather, that the interesting possibility of linear systems is that small residual or marginal spaces that are often ignored or neglected can be stitched together with other open spaces and natural areas into a larger structure of open spaces. Such an approach would greatly aid our struggle for expanding open spaces in dense cities where open lands are in short supply, helping us to achieve minimum open spaces standards.

In terms of physical planning, at P.K. Das & Associates we aim to develop contiguous open spaces by interconnecting various facets of areas open to the public. This would produce a network of green corridors throughout the city and its various localities, nourishing community life, neighbourhood engagements, and participation. With public space being the main planning criteria, we hope to bring about a social change: promoting collective culture and rooting out alienation and a false sense of individual gratification promoted by the market. By achieving intensive levels of citizens’ participation, we wish to influence governments to devise comprehensive urban plans and to integrate disparate developments. The ‘open and clear forever’ public space policy will truly symbolize our democratic aspirations. This is a significant way to rebuild humane and environmentally sustainable cities.

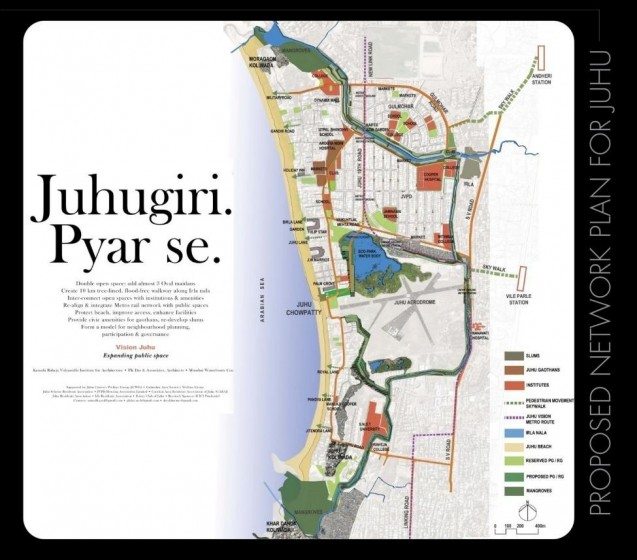

In Mumbai, the ‘Mumbai Waterfronts Centre’ and architects PKDas & Associates have made an attempt to re-envision the city by proposing such a linear public spaces structure, bringing together the vast extent of the natural assets and the available open spaces within the city. An illustration of such an idea shows how a system of linear parks and other public spaces can radically alter the socio-environmental character of the city. More importantly, by this plan, it is possible to mobilise neighborhood people’s participation in the development and expansion of open spaces as much as their participation in the development and expansion of the city, as seen in the plans for Juhu, a neighborhood in the western suburbs of Mumbai.

In order to Re-Vision Mumbai and democratize its public space, we have launched the ‘Vision Juhu’ plan as a pilot project.

As Mumbai expands, its open spaces are shrinking. The democratic ‘space’ that ensures accountability and enables dissent is also shrinking, very subtly but surely. The city’s shrinking physical open spaces are of course the most visible manifestation of this, as they directly and adversely affect our very quality of life. A new order of linear open spaces must clearly be the foundation of city planning.

Through this plan we hope to generate dialogue between people, governments, and professionals and dialogue within movements working for social, cultural, and environmental change. It is a plan that redefines land use and development, placing people and community life at the centre of planning—not real estate and construction potential. A plan that redefines the ‘notion’ of open space to go beyond gardens and recreational grounds to include the vast, diverse natural assets of the city, including rivers, creeks, lakes, ponds, mangroves, wetlands, beaches, and the incredible seafronts. A plan that aims to create non-barricaded, non-exclusive, non-elitist spaces that provide access to all our citizens for leisure, relaxation, art, and cultural life. A plan that ensures open spaces are not only available, but are geographically and culturally integral to neighbourhoods and participatory community life.

Through this plan we hope to generate dialogue between people, governments, and professionals and dialogue within movements working for social, cultural, and environmental change. It is a plan that redefines land use and development, placing people and community life at the centre of planning—not real estate and construction potential. A plan that redefines the ‘notion’ of open space to go beyond gardens and recreational grounds to include the vast, diverse natural assets of the city, including rivers, creeks, lakes, ponds, mangroves, wetlands, beaches, and the incredible seafronts. A plan that aims to create non-barricaded, non-exclusive, non-elitist spaces that provide access to all our citizens for leisure, relaxation, art, and cultural life. A plan that ensures open spaces are not only available, but are geographically and culturally integral to neighbourhoods and participatory community life.

Such plans for cities will be the beginning of a new dialogue to create a truly representative ‘Peoples’ Plan’. Let streams of linear open spaces flow across urban landscapes, defining a new ecology—socio-environmental order—of cities the world over

PK Das

Mumbai

Leave a Reply