about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

Insurance is the common modern hedge against risk. We pay in advance as a bet against later uncertain, but potentially larger, costs. The insurance industry (and sometimes society) helps mediate this risk mitigation strategy for us.

Urban life in a climate changed world presents risks to life, livelihood, and property. These risks, when they materialize, are costly, and sometimes catastrophic. When should they be borne? By whom? How much should be invested in risk reduction in advance? These are questions for our societies and for the organizations that contemplate and mediate risk, including the insurance industry.

Nature-based solutions and urban ecosystems (through the services they can provide) mitigate some of these risks. So, it is logical to ask: if nature-based infrastructure — such as wetland buffers, storm water catching bioswales, etc. — are effective mitigations for ocean surges and storms, what is their insurance value?

Nature-based solutions and urban ecosystems (through the services they can provide) mitigate some of these risks. So, it is logical to ask: if nature-based infrastructure — such as wetland buffers, storm water catching bioswales, etc. — are effective mitigations for ocean surges and storms, what is their insurance value?

As an example, in the New York metropolitan region, Hurricane Sandy caused approximately 50 billion $US in damage, much of which was paid as claims to insurance (or lost altogether). What if we paid some of the costs of risk mitigation in advance by building on green infrastructure that provide protective ecosystem services? This is what insurance underwriters require of us when we insure our homes against, say, fire—that we reduce the chance of risk in advance. Should we not take the same strategy for resilience?

Or is the construction of nature-based mitigations and adaptations to climate change, in the form of large green infrastructure, solely a issue for government?

The insurance industry surely has a stake in this topic. What is it? What role can or does the industry take, either in a formal way, or to propel policy discussions?

about the writer

Victor Beumer

Victor Beumer works at Deltares, where he is coordinator of the working group Green Infrastructure of the EU Water Platform.

Victor Beumer

Urban ecosystems have no insurance value. Let me elaborate this statement with an example of the application of ecosystem restoration for the purpose of climate adaptation in urban riverine systems.

In the region of Rotterdam, The Netherlands, we are active in a consortium whose ambition is to make urban river shores more natural. It concerns the river Meuse that flows through the city and has a tidal dynamic. The different partners have different goals — the city itself is trying to find ways to the increase livability in the city, especially in their water system, but also to create awareness among its citizens of living in a tidal water system. The Port of Rotterdam has the interest of balancing its portal growth with environmental quality and practicing circular economy. Worldwide Fund for Nature has set their goal to increase natural value in the tidal river system in and around Rotterdam, while the Dutch State water service (RWS) has requirements to generate a certain amount of natural shores to reach the criteria of Water Framework Directives (WFD). Deltares is developing knowledge that is combining these ambitions in nature-based solutions and strategies to implement them.

You may notice that no partner is committing itself to the ambition of climate adaptation, while it would perfectly fit in the program. I think two reasons may have resulted in this. First, it might be unclear who is responsible for climate adaptation, not only because measures toward climate adaptation are extremely complicated and expensive but also because of the complex governance behind it. In the Netherlands we deal with water boards, provinces, municipalities, and the state itself regarding these issues. I can imagine some countries may have even more complex structures, or an absence of structure at all. Second, despite the extensive research on climate adaptation and accompanying solutions, it is very hard to pinpoint the effectiveness of riverine ecosystems on the mitigation of climate change effects in urban settings.

Now back to my statement: urban ecosystems have no insurance value. I think there are three clear reasons that underlie my statement:

- It is rather uncertain how much the restoration of an urban ecosystem will provide in the mitigation of climate change effects; for example, to what extent restoration would prevent unwanted flooding. Top-end research institutes already have trouble making a quantitative correlation between restoration measures and mitigation benefits; therefore, an insurance company will never invest in such measures.

- You must consider that an insurance company works with a proven business model. If it were not for highly extreme weather events (of which most are excluded from the insurance contract), damage costs are consumable. After a season of high damage costs, the insurance company will simply increase the yearly insurance premium to their clients in order to balance the business model again.

- If measures for the mitigation of climate change effects would have an insurance value, why isn’t it that dikes and drainage measures with a civil-engineered character are financed with insurance capital? In such cases, it is much clearer what the exact quantitative benefits are from building a dike or setting up a drainage system than in cases of restored ecosystem services.

It may seem I have no faith in the potential impact of the insurance industry in the restoration of ecosystems for the purpose of mitigating climate change effects. But it is the opposite — I think the insurance industry is a major stakeholder in these situations. They have the ability to initiate processes of spatial change because of their position in a society: their lobby-power and their indirect effect on the attractiveness for citizens to live in a city where insurance costs are rising.

about the writer

Henry Booth

Henry Booth has worked for over 31 years as an insurance archaeologist. He specializes in the reconstruction and analysis of historical liability insurance coverage for US policyholders.

Henry Booth

The insurance industry has experienced, and counted the cost of, severe hurricane damage, protracted drought, and other natural catastrophes and has been described as “being on the front line” of climate risks. It would seem axiomatic that those working in insurance have an interest in supporting efforts to mitigate the consequences of disasters exacerbated by, or even wholly attributable to climate change. Readily available statistics (see, for example, National Association of Insurance Commissioners & The Center for Insurance Policy & Research on climate risk) regarding losses incurred since the turn of the 21st century provide further evidence that it would behoove the insurance industry to back urban decision making that promotes natural ecosystem solutions and enhanced resilience.

In the course of considering this question, I came upon various analyses in which the value of ecosystem benefits and initiatives was quantified. The cities involved were geographically diverse and included Toronto, Canada (greenbelt benefits, annual value $2.7 billion CDN) and Canberra, Australia (tree planting initiative, value over 4 years $20-67 million US). Belgian and Chinese ecosystem value assessments, sponsored by ICLEI-Global.org, were also detailed. These reports described the insurance value for ecosystem services as the contribution of green infrastructure and ecosystem services to increased resilience and reduced vulnerability to shock.

I also saw a treatise titled “Estimating the insurance value of ecosystem resilience” which analysis included calculations leading to the actual quantifying of the insurance value. The subject of the study was an area of farmland north of Melbourne, Australia, that is threatened by salinization due to rising water tables. The authors concluded that ecosystem resilience provides a sizeable economic insurance value. Here, at least theoretically, was some kind of hard data to support a discernible value that should be recognized by the insurance industry, who can underwrite accordingly.

It seems, however, from various studies by organizations such as Ceres, a non-profit advocating sustainability leadership, as well as by reference to articles in the news media, that the insurance industry is not exactly hurtling into the leadership role that might have been expected of them in this area. As a practical matter, for there to be a real insurance value of urban ecosystems and their services, I suppose that the industry has to be engaged in a way that, at least thus far, they are not.

Why not?

I have seen the phrase “ecological threshold” (ET) used in this connection and I think it provides one reason as to why most insurers in the US marketplace have provided a poor response in terms of leadership in the face of the worsening global impact of climate change . The ET is defined as “the point at which a relatively small change in external conditions causes a rapid change in an ecosystem”—in this sense, the ET is a measure of resilience. To the extent that the ability to quantify the insurance value of ecosystem servicesis affected by the distance to the ET (i.e. the closer the distance to the ET, the more susceptible to error any such valuation is), the riskier the underwriting of insurance for entities, such as cities, that may be at the margins of the ET, becomes.

Another reason that the insurance industry doesn’t want to engage natural solutions may be found in the evaluation of their exposure to underwriting losses by the Association of American Insurers (AIA). The AIA has said that most of their property/casualty product lines have limited or no exposure to climate-change-related losses. For the lines that do have exposure, weather is only one among a number of covered perils bringing in premium. This spread of product lines allows for stability, at least for the insurers, who can offset a possible loss-making line by multiple lines bringing in premium revenue. In addition, it is worth remembering that in the USA, flood and crop insurance are federal programs in which the insurance industry participates through administration—including policy issuance and claims handling—but not in terms of any negative financial exposure. This calls into question their incentive (at least financially) to support urban ecosystems as a means of mitigating risk.

Still, the AIA talks up its ability to respond and adapt in the face of changing conditions and generally supports sustainable development initiatives, provided they have been thoroughly examined and determined not to have the potential to create new hazards. The Ceres’ survey I mentioned above quotes the NAIC as encouraging insurance industry leaders to take the challenge presented by climate change more seriously. Couched in terms of relieving possible financial insolvency and protecting the insurance consumer, they say that insurance industry is uniquely positioned as a risk-bearer to reduce the impending impact of climate change.

Based on what I have seen, the “talk has been talked” by insurance industry regulators and commentators and the potential insurance value of ecosystem services has been ‘actuarialized’. But, for the reasons discussed above, so far this has not yet convinced the US insurance industry to “walk the walk.”

This may also be due to fear of the unknown and a desire not to let history repeat itself. My work is concerned with latent injury claims such as may arise through exposure to asbestos or as a result of environmental contamination. In this world, case facts and appropriate proof of coverage permitting, Comprehensive General Liability (CGL) insurance policies written as far back as the 1930s may respond to a modern claim. Because the insurance industry was marketing its new CGL product in the late 1930s (as well as related coverages over time), it was keen to point out that CGL covered everything that was not expressly excluded. The greed of the marketplace and breadth of coverage written caused massive insurer insolvency from the 1980s forward, including (almost) bringing down Lloyd’s of London.

Likewise, in 2004/2005 I worked on behalf of a large mid-western city whose liability insurance included coverage for their airports. After a convoluted process, the case—involving environmental property damage at, and adjacent to, the airport—settled for cents on the dollar relative to the actual limits of liability purchased by the city. There were some solid reasons for this, but also some knee jerk insurer activity designed to reduce their dollar exposure which, in order to get out from under the case with some not trivial money, the city accepted. This illustrates several things which a city seeking “insurance value”—e.g. a reduction in premium—on account of systems put in place to mitigate possible future losses from climate change-related events would do well to remember.

As a result of cases like these, claims are picked through in the utmost detail before any payment is made. And new frontiers, such as the evaluation of ecosystem for insurance purposes, are a long time in the reaching.

about the writer

Mitchell Chester

Mitchell A. Chester, Esq. is a trial attorney licensed in the State of Florida. In practice for 37 years, he is focused on identifying and seeking solutions to emerging legal and financial issues created by sea level rise (SLR) and climate impacts.

Mitchell Chester

Insurers, bond rating companies, and local governments as proponents of natural fortifications in vulnerable communities

As Naomi Klein points out in her excellent work, This Changes Everything, some insurance industry giants have been very vocal about climate risks, but have not done much to promote proactive climate policies to assist local communities.

Our maturing century of an evolving new environmental reality demands a more proactive community involvement by casualty and property companies and re-insurers, which assess and thrive on hazard exposures. Should they fail to take a more active public stance to deal with rising seas, significant opportunities to insure will soon be lost to the industry, insurance consumers will suffer, and society will fall further behind in needed adaptation and mitigation measures. The end result of such neglect may hasten the day when “retreat” strategies are utilized with more urgency than would be necessary if we had started to connect seemingly unrelated tools.

A curious opportunity thus presents itself. How can the risk industry use natural systems to prepare our towns and cities to maintain public and private economic resources, jobs, and infrastructure? Can a link be made between nature based coastal defense systems and insurance boardrooms? How can large insurers promote utilization of coastal forests, beach and dune restorations, fortified berms, wetlands, coral reefs, mangroves, oyster formations, and reforestation efforts to shore up their premium providing markets?

What stakeholders can be recruited to forge a financial nexus that will empower a partnership between political leaders and insurers to facilitate the public good? In the multiverse of climate change psychology, we can start thinking differently.

Let’s connect some major players.

Insurers depend on the need of local communities to have financial security so that underwriters can continue to provide their varied products. When those markets are challenged by climatic events such as progressive sea level rise, underwriters need to extend their current horizons beyond their usual annual financial risk analysis and partner with communities in natural and urban eco-system fortification strategies. The stakes are very high; the need for new economic strategies to prepare is urgent. According to RiskyBusiness.org, in the United States, “by 2050 between $66 billion worth of existing coastal property will likely be below sea level nationwide.” That’s just the beginning, and probably a conservative estimate at that. Mid-century is not that far away.

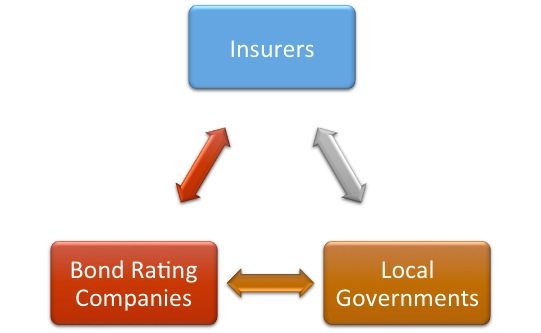

The goal is to extend the insurability of the very same risk-vulnerable communities that create yearly premium revenues for insurers. A successful enterprise-level public initiative joining insurance-oriented public-private partnerships with other financial stakeholders is a key opportunity. For example, bond rating companies which team up with insurance industry stakeholders to support nature-based protection solutions can forge an intelligent strategy to help local and regional governments answer tough questions about readiness for some climate events.

This formula would be a positive for both the insurers (by promoting the opportunity to retain insureds as customers for as long as possible in communities threatened by encroaching waters) and political leaders (who need solid bond ratings for public infrastructure). An important by-product of this type of teamwork would be a more durable coastline that protects the “built environment.”

There are historical examples of the insurance industry acting beyond current modes of insurer operations. According to Dr. Evan Mills, Staff Scientist for the Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory, insurers were a motivating force in the creation of early fire departments and acted as advocates for building codes. Now there are new opportunities. Dr. Mills adds, “While the primary focus in recent years has been on financially managing risks, physical risk management is receiving renewed attention and could play a large role in helping to preserve the insurability of coastal and other high risk areas.”

How can we move insurers beyond improving building codes and into nature-based risk reduction? Insurers can structure their proactivity to support construction of natural coastal defense systems through these strategies:

- Education of vulnerable insurance consumers about how adapting to climate events using nature-based defense strategies is a good place to start to create public support for the innovative solutions that can be employed by public officials. Grassroots endorsements of such programs, combined with public advocacy for the use of natural systems to protect regions, is a way to spark political will currently lacking in many public officials. According to the Insurance Information Institute, in September 2014, there were already examples of insurance industry advocacy for revised building codes. For example, in some parts of Southeastern Florida, new structure standards are being proposed and implemented in reaction to scientifically peer-reviewed studies about sea level rise. Beyond such efforts, promoting the use and construction of natural coastal defenses should be added to the list of insurer tools to reduce risk and to promote mitigation.

- Large insurers can agree to insure multi-million dollar (or more) coastal developments with certain criteria as pre-conditions. For example, large projects on estuaries, inlets, and other coastal areas can be required to construct substantial wetland protection zones to help safeguard the insured’s investments and the risks assumed by the carriers. In locations where wetlands and other coastal defenses cannot be built or properly restored (and meaningful set backs are not physically possible), insurers can decline to accept the mounting risks that will be associated with such construction, while at the same time inducing potential insureds with financial incentives if they move their projects to more sustainable locations. Such incentives can be a major factor in motivating strategic, climate-smart placement of new hotels, office buildings, other commercial properties, and private residences in areas which are less susceptible to sea level rise and more affordable to insure when losses occur. The lesson is clear: Natural systems for coastal areas equals reduced risk. This approach takes insurers beyond the important but limited “green building” approach, such as LEED Certification, to what can be called a “green footprint” policy, which advocates environmental responsibility beyond the walls of built structures and into their surrounding neighborhoods.

- Insurers can partner with municipal bond rating agencies to induce responsible governmental and insurance consumer action in promoting natural system defenses in coastal areas. This relationship can help identify needed infrastructure improvements at the “micro” level. “Local government credit quality,” which is measured by the health of municipal bond ratings when viewed from the perspective of climate threats, is already being watched by powerful entities such as Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s Investor Service, and Fitch Ratings. If local governments are not proactively able on their own to handle climate risks such as swelling oceans, they will ultimately receive lower credit ratings. Ignoring this naturally symbiotic fiscal relationship will produce a cycle of lower willingness to insure in areas that are suffering from lower bond scores. However, by enthusiastically working with municipal rating agencies to prevent credit downgrades, property and casualty and re-insurers can help consumers and local governments act stronger with regard to the risks they face. Intelligently slowing advancing waters can also fortify bond ratings so local governments can entice continued investments for public infrastructure needs.

- Insurers can direct their investment dollars toward sea level rise adaptation projects in exchange for user fees. Public-private partnerships are great at such relationships. Just as Dragados USA invested in the expansion of Interstate 595 in Southeastern Florida in return for user fees on express lanes, insurers can infuse dollars into construction of natural defense systems in exchange for receiving neighborhood impact fees paid by local beneficiaries such as businesses, municipal governments, and homeowners.

* * *

Government has limited financial resources. The same is true for private sector stakeholders. Each is interdependent with the other in the fight to fortify, for as long as possible, threatened coastal areas. They have an emerging role to play in supporting natural systems to reduce the risk in advance of storm surge, progressive sea level rise, saltwater intrusion, and tidal flooding. As the science of sea level rise advances, so too must our collective economic psychology to bring new players to the adaptation and mitigation fight.

about the writer

Thomas Elmqvist

Thomas Elmqvist is a professor in Natural Resource Management at Stockholm University and Theme Leader at the Stockholm Resilience Center. His research is on ecosystem services, land use change, natural disturbances and components of resilience including the role of social institutions.

Thomas Elmqvist

To date, the insurance value of ecosystems has been largely overlooked in research and practice and mostly discussed in relation to its role as a metaphor for the value of resilience. However, the concept has recently gained a lot of interest. The latest is an initiative within the EU to base economic development in Europe on nature-based solutions, where maintaining and strengthening the insurance value of ecosystems is a cornerstone.

The reason for this interest is partly that global natural disasters have shown a clear increasing trend. The annual reported economic damages from natural disasters have risen from less than 100 billion $US in 2000 to above 300 billion in 2011 and, between 2002 and 2013, natural disasters led to more than 80,000 fatalities and several hundreds of billions euros of damages in the European Union alone (European Commission, 2014). At the same time, studies have demonstrated the benefit of investment in natural capital and green infrastructure to reduce risks of disasters. For example, according to Korea Environment Institute (2011) for the year 2010, a 1 percent increase in size of green infrastructure, which includes parks, urban forests, and green roofs, is estimated to bring 6.4 percent reduction in economic loss caused by flooding in the cities of Korea.

So how do we include these values in development and urban planning?

Several attempts are now made to develop and operationalize the concept of insurance value of ecosystems. Currently, there are two definitions of the insurance value of ecosystems. The first emphasizes the capacity to generate ecosystem service benefits by maintaining a system within a given regime, despite disturbance and management uncertainty. This definition is closely linked to definitions of resilience and includes a more explicit economic approach. The second definition puts more emphasis on the value of the sustained capacity of ecosystems to reduce risks to human society caused by, for example, climate change-related excess precipitation, temperature, or by natural disasters (Expert group DG Research 2015); it more specifically targets disaster risk reduction.

A combination of the two seems like a way forward: where the insurance value of an ecosystem results from the system itself having the capacity to cope with external disturbances, and includes both an estimate of the risk reduction due to the physical presence of an ecosystem (e.g., the area of upstream land/number of downstream properties protected) and the capacity to sustain risk reduction (i.e., the resilience of the system).

Recognizing the effect of green infrastructure, the European Commission (EC) has initiated EC Green Infrastructure Strategy to promote green infrastructure in the EU. In fact, Target 2 of the EU 2020 Biodiversity Strategy requires that “by 2020, ecosystems and their services are maintained and enhanced by establishing green infrastructure and restoring at least 15 percent of degraded ecosystems.” This project aims to enhance quantity and diversity of urban green areas to increases security against natural disasters, which are projected to increase with climate change.

There is an urgent need to scientifically explore methodologies and conceptual frameworks for assessing the insurance value of nature and to integrate this into the disaster risk management agenda. This could be done, for example, by working with financial institutions and insurance companies to develop innovative ways for promoting nature-based solutions for risk management.

One strategy could be to translate risk reduction capacity into value through calculating benefit/investment ratios in landscape management and restoration. Here, the benefits would represent the reduced risk and potential lower premiums of land and property insurance policies. A new legal framework that serves to create incentives for maintaining or enhancing the insurance capacity of ecosystems should be explored. It would be important to first develop a framework where the models and data (including downscaled climate change scenarios) capturing the capacity of ecosystems to reduce risks are made compatible and harmonised with the risk assessment models and data used by the private insurance sector.

A complementary strategy would be to develop an economic approach to understanding ecosystems as representing the stock that generates the flow of services and to explore how to capture the long-term benefits of maintaining and enhancing that stock.

Thirdly, we should explore the cultural dimension of the insurance value of ecosystems and people’s perceptions of risks and insurance.

about the writer

Alexandros Gasparatos

Alexandros Gasparatos is Associate Professor of Sustainability Science at the University of Tokyo. As an ecological economist, he is interested in the development, refinement, and application of sustainability assessment and ecosystem services valuation tools.

Alexandros Gasparatos

Living in Tokyo, you become no stranger to the occasional typhoon or earthquake. And you can’t help but notice how the natural environment has been completely shaped throughout Japan, partly to reduce the risk of such events. Indeed, the need to ensure the safety of the population and the resilience of the socioeconomic system does not need to be overemphasized in a metropolis which is both the home of over 35 million people and the economic heart of the world’s 3rd largest economy.

As an ecological economist, I have been trying for several years to persuade others about the multiple benefits that we derive from nature. I whole-heartedly believe that urban ecosystems can indeed insure against certain environmental risks and offer co-benefits such as biodiversity conservation and cultural ecosystem services (e.g. recreation).

However, I also see three highly interconnected reasons that will make it very challenging to adopt such solutions, at least in the short-to-medium term. This is especially true in highly disaster-prone countries such as Japan, where the safety of the population following the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake sometimes overrides economic rationalities.

The first reason that urban ecosystem-based insurance solutions will be difficult to implement has to do simply with the several unknowns surrounding the feasibility and effectiveness of urban ecosystems to insure against different natural hazards, let alone the “reproducibility” of nature-based solutions, especially if we aim for their widespread adoption. More importantly, are there certain thresholds over which ecosystems cannot insure against these risks? And what are these thresholds?

Engineered mitigation strategies usually undergo a series of tests and refinements, both under laboratory and real-life conditions. So there is usually a threshold of (un)certainty about what these strategies can achieve and under what conditions. Undertaking this process with ecosystems (particularly undisturbed ecosystems) is a much more complicated task that is highly reliant on natural experiments. As a result, it can be subject to longer and more difficult verification processes.

The second reason has to do with public acceptability of mitigation solutions and how it can vary not only between different types of natural hazards (and severity levels), but also between cultural and socioeconomic settings. In some settings, “using nature to guard against disasters” equals “taking no mitigation action”. While I do not subscribe to this viewpoint, I cannot help but acknowledge that in such contexts it would be next to impossible to adopt nature-based solutions for disaster risk mitigation. This is because a decrease in the intended benefit of nature-based solutions, i.e. disaster mitigation to ensure the safety of the population at risk, will trample the provision of any other co-benefit that could be added in the equation.

The third reason has to do with assigning (and accepting) responsibility in the event of failure. Even if a nature-based solution is acceptable to the public, it is the decision maker adopting it that will ultimately be scrutinized in the event of a failure. I tend to believe that a nature-based solution will not be preferred over an engineered solution even if it was acceptable by the public, in part because a line of responsibility can be traced from the decision maker to the provider of this solution. A level of “quality” could be assured for an engineered solution, but would it be feasible to assure a level of “quality” in a disaster mitigation service offered by an ecosystem? Who would make such an assessment? An academic or a consultant could quantify (one way or another) the monetary benefits delivered from such an ecosystem service, but could they put their reputation on the line and “vouch” for the level of quality of the service that was ultimately delivered by an ecosystem?

I strongly believe that research could bridge several of the current knowledge gaps and possibly allow for the assurance if the “quality” of risk mitigation ecosystem services. Ultimately, I am highly skeptical that it will be easy to enhance the acceptability of ecosystem-based solutions for the public and decision makers. This might prove to be a too difficult hurdle in high disaster-prone environments such as Japan.

about the writer

Jaroslav Mysiak

Dr. Jaroslav Mysiak is the director of the research division ‘Risk assessment and adaptation strategies’ at the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change and senior scientist at the Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei. His research concentrates on environmental economics and governance, and climate risk and adaptation.

Jaroslav Mysiak

Disaster insurance and nature-based solutions

The recent upswing of interest in disaster insurance from European policy makers and the revitalised appreciation of ecosystem services and nature-based solutions has coalesced into a notion of insurance value of ecosystem services. This term should not be understood as implying that insurers gain from or make a profit out of ecosystem services. Rather, it should be explored what role disaster insurance can (or should) play for conservation and restoration of environment.

In many places, ecosystem services (ESSs) attenuate natural hazard risks, locally or regionally, and hence have an economic value in the context of natural disaster insurance, even if no price actually is paid for their provision and/or maintenance. The implicit value of ESSs is the price difference of insurance under marginal changes of ESSs provision. In other words, it is the price differential for risk premiums homeowners pay for having their property insured, and what they would have to pay if the existing risk-mitigating ecosystem services were somehow eroded. Where, for example, ecosystems such as forests or wetlands in the upstream basin area do reduce or delay peak flow discharges, the flood risk and hence insurance prices are lower than in other places where no similar risk-mitigating ecosystem service is available.

Insurers do not trade with the ecosystem services; the latter are a part of the baseline risk calculations. ESSs are a public good that is both non-excludable and non-rivalrous. Their implicit utilisation does not distort the market and competition because all insurance undertakings have equal access to ESSs. The question is whether insurance prices can be used as an incentive for ecosystem conservation or an instrument (one of many) for recovering the ensuing costs?

Individual commercial insurance contracts are perhaps less suitable as incentives to this end, but other forms of insurance, including mutual and community-based schemes, may foster reduction of negative environmental externalities such as surface water drainage discharges. Because flood risk increases as a result of collective externalities, co-operative insurance can reward individual efforts to reduce surface runoff from one’s own property. Whether insurance is a better way that land or property taxes or rainwater collection charges should be explored by targeted research and policy trials.

Using insurance contracts for recovering costs of ecosystem restoration and maintenance is more prone to controversies. Whereas the ‘polluter-pay-principle’ (PPP) is firmly rooted in the European Treaty and secondary environmental legislation, the ‘beneficiary-pays-principle’ (BPP) is not. The European Commission (EC) does consider flood protection as a water service, the costs of which are to be recovered by water prices. But the sentence of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in the case Commission against Germany did not back-up the position of the EC, and the ECJ ruled that, as long as the (environmental) objectives are met, it is at the discretion of the national governments to choose the best suited policy instrument. But even in this case, the ecosystem services were not at the heart of the dispute.

There are practical and ethical aspects in the application of BPP. From a practical point of view, it is difficult to trace the individual benefits of ecosystem services. Hence, any attempt to apply BPP in practice will result in burdensome evidence collection and high transaction costs. Because those property owners who benefit most from existing ecosystem services are those who see the largest saving in risk premiums, the BPP would possibly need to use inverse proportional charges and transfer of collected revenues to areas where the ecosystems are degraded and need to be restored. From an ethical point of view, the BPP clashes against arguments related to social justice and historical responsibility for environmental changes. It is worthwhile, however, for public authorities and private insurers to liaise to explore mutually beneficial partnerships. If nothing else, an open public debate about the ‘insurance value of ecosystem services’ may contribute to exploring synergies between ecosystem preservation and disaster risk reduction.

about the writer

Rob Tinch

Dr. Rob Tinch has 20 years' experience in environmental/ecological economics. Based in Brussels, he works mainly on European research projects.

Rob Tinch

Should we value the insurance services of urban green infrastructure?

Resilience of urban systems is an increasing concern, and urban green infrastructure has an important role to play in providing services and enhancing resilience. It may seem logical that we should attempt to value this ‘insurance value’, to incorporate these values in decision support and urban planning. And there is excellent research being carried out into this issue, on both theoretical and practical levels.

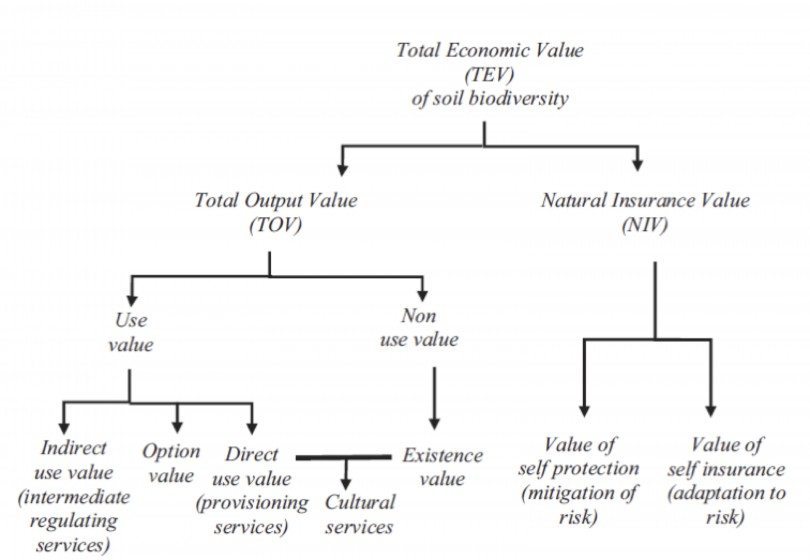

McPhearson et al. (2014) argue that insurance value reflects “the maintenance of ecosystem service benefits despite variability, disturbance and management uncertainty”. Pascual et al. (2015) make space for ‘natural insurance value’ (NIV) as a component of ‘total economic value’, with the more conventional components (use and non-use values) being classified as ‘total output value’ (TOV). Pascual et al. further divide NIV into ‘self-protection’ (lowering the risk of a disturbance event) and ‘self-insurance’ (reducing the size of loss from an event). NIV is quite a specific concept relating to “the value of one very specific function of resilience: to reduce an ecosystem user’s income risk from using ecosystem services under uncertainty” (Baumgärtner and Strunz, 2014:22).

There are problems in operationalising this framework in valuation. Private discount rates are high, so private decisions about green infrastructure and insurance are likely to be socially sub-optimal. Non-linear relationships (edge effects, minimum viable areas, network effects…) will play an important role, making marginal valuation challenging and reducing scope for value transfer.

But these problems are not insurmountable, and valuation can be attempted. For certain types of infrastructure (e.g. natural flood defences) this could be done via expected damages and/or conventional prevention costs avoided. NIV can also form the basis of a stated preference instrument. For example, Figueroa and Pasten (2015) value local climate regulation services of forests via the change in insurance premium that risk-averse individuals are willing to pay when forest cover changes.

If, however, we’re thinking about long-term resilience to extreme scenarios and threats—as in adaptation to high-end scenarios of climate change—then conventional valuation faces serious limitations. We’re talking about different people, preferences, social-economic structures, technologies. There is high uncertainty about risks of disturbances, extrapolation well beyond current experience, unknown tipping-points/thresholds, irreversibilities and feedbacks. Under these circumstances, conventional valuation and CBA break down: their numerical ‘clarity’ becomes “especially and unusually misleading” (Weitzman, 2007). Standard welfare functions work for stable/increasing consumption paths but fail to reflect views on overshoots, fluctuations, and long-term threats to existence. Reducing complex, uncertain paths to expected present values destroys information on distribution across generations, on uncertainty regarding outcomes, and on risks of catastrophic/unacceptable outcomes.

Within a decision support context, therefore, the question of the ‘value’ of insurance might be of rather less interest than the question of the range of scenarios for which green infrastructure provides resilience, either in terms of security of a particular service, or more generally in terms of flexible natural capital stocks that could be designed to buffer against a wide range of possible scenarios. Aiming to pass flexible stocks and opportunities to future generations may be a much more useful goal than aiming to optimise expected present values given huge uncertainties. Attempting to value insurance from green infrastructure runs a risk of bringing a short-term, expected value focus to inherently long-term, resilience-providing investments. While attempts to value natural insurance are academically interesting, the insurance role of urban GI should be considered in the light of precaution, flexibility, adaptation and resilience-enhancing criteria, not expected values.

Acknowledgement: The ideas presented in this note have been prepared during work under European Commission contracts n° 603416 IMPRESSIONS (http://www.impressions-project.eu/) and n° 308393 OPERAs (http://www.operas-project.eu/ )

References:

Baumgärtner, S., Strunz, S., 2014. The economic insurance value of ecosystem resilience. Ecol. Econ. 101, 21–32.

Figueroa, E., & Pasten, R. (2015). The economic value of forests in supplying local climate regulation. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics.

McPhearson, T., et al., Resilience of and through urban ecosystem services. Ecosystem Services (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.07.012i

Pascual, Unai, Mette Termansen, Katarina Hedlund, Lijbert Brussaard, Jack H. Faber, Sébastien Foudi, Philippe Lemanceau, and Sisse Liv Jørgensen. “On the value of soil biodiversity and ecosystem services.” Ecosystem Services 15 (2015): 11-18.

Weitzman, M.L. (2007). A review of the Stern Review on the economics of climate change. Journal of Economic Literature, 45:3, 703–724.

about the writer

Francis Vorhies

Francis Vorhies, the executive director of Earthmind, works on the interface between biodiversity, business, and the economy.

Francis Vorhies

Yes, we can mitigate disaster risk by investing in nature-based protection scheme areas. This includes natural areas set aside and managed for storms and floods. Such measures will reduce the costs of insuring for disasters, and the industry is capable of estimating cost reductions and adjusting insurance rates accordingly.

Importantly, investing in urban disaster risk mitigation can also have important economic and social co-benefits. Natural areas managed for risk mitigation can also be important areas for conserving biodiversity. The management programmes for these areas can also engage local communities, raise awareness on environmental protection, and provide learning opportunities for young and old alike. And, of course, natural areas can be important areas for recreation and relaxation.

Thus, investments in nature-based risk mitigation can strengthen environmental and social resilience within an urban area. In so doing, these investments further enhance the capacity of the area to mitigate disasters when they do occur. This in turn further reduces the potential costs of disasters and hence should lower the rates for insuring against these disasters. Do insurance companies recognize these savings?

This implies that there is both a public and a private benefit to more clearly articulating the co-benefits of disaster risk reduction.

But who will undertake the work needed to make these benefits transparent to the local policy makers and to the insurance industry? Perhaps this is a task for university researchers or for civil society organisations. Or perhaps the information scientists are providing is somehow not of the right form and this is a task for communicators.

How do we articulate the environmental and social co-benefits of disaster risk reduction so that it clearly understood by the insurance industry and its customers?

about the writer

Henrik von Wehrden

Henrik von Wehrden isa professor of natural science methods at Leuphana University in Lueneburg, Germany.

von Wehrden

What is the optimal sustainable size and management strategy of a city? Adding to the rising debate on optimal city sizes, the ecosystem service concept is increasingly recognized in urban planning. However, much of the literature to date focuses on biophysical entities of ecosystem services. Of course, planning of biophysical aspects of ecosystem services such as climate regulation or flood protection are surely necessary and helpful, but recognition of the perceptions and needs of citizens is also important. More research is needed that considers both normative perceptions and engages in transformation towards a more sustainable state of the given system.

Normative perceptions demand recognition of stakeholders, a labor intensive and often context-dependent task. However, recognition of stakeholders and their perception is crucial when it comes to recognition of the insurance risk, as it is stakeholders who will ultimately endure potential risks and claim compensation. Many urban settings are designed for the people, when they should be designed by the people. When cities started to grow massively, urban planners attempted to separate living from working, and commuting drastically increased. This potentially also led to higher disparities of risks between different neighborhoods, where some areas are at higher risk of catastrophic events than others. This concept was dramatically illustrated by the effects of Hurricane Katrina, where some neighborhoods suffered higher impacts than others.

Today, there is a global trend towards a recognition of functional diversity within cities, meaning that separation of different functions in urban settings often decreases. Neighborhoods with a higher diversity in function and ecosystem services may support a higher quality of life for citizens and a better resilience against drastic changes or catastrophes we face today. The concept of ecosystem services should therefore enable a diverse and resilient setting of services.

Urban planners should, in my opinion, not make the mistake of focusing on short-term optimization by using the ecosystem service approach. In contrast, planners need to include long-term effects of different ecosystem services signatures into their planning process. Costs that protect urban setting from rare catastrophes, especially, may only pay off on a long-term perspective. Planners and citizens need to recognize the value of these long-term services, where settings that are tightly planned may not allow for systems to tackle extremes, and may fail to deliver a just urban setting. Many stressors of urban environments are extreme by nature. Calculation of average system entities is relevant, but current challenges also demand the integration of extremes, including the interplay of extremes. For example, if heatwaves alter soil infiltration capacities, torrential rainfalls later in the year then create devastating floods. Recognizing trade-offs is, in my opinion, one strongpoint of the ecosystem service concept. Understanding the interplay between a variety of services and their temporal long-term dynamics can help us to build a better system understanding. While this is, in part, context dependent, many solutions are also transferable across different neighborhoods and economies.

Disparities are not only found within cities, but also between different economies. While insurance risks are comparably well accounted for in parts of Europe and North America, urban environments in most of the world are not covered by insurance, but are often threatened by risks. Insurance often focusses on individuals, but risks can threaten whole neighborhoods or even cities. Insurance can thus increase injustice within cities, where only those people that can afford insurance are protected. The costs of long term planning endeavors need to be added to the costs of urban settings, both for urban planners and citizens. While urban living would thus become more expensive, it may create a more just setting for all citizens. This may enable more sustainable planning for future cities by increasing equity and justice in cost calculation of urban areas. If this price is too high for citizens and planners, then we will continue to rely on insurances and tackling catastrophes only after they hit us.

about the writer

Koko Warner

Dr. Koko Warner is a Senior Scientist at the United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security, where she leads the Environmental Migration, Social Vulnerability & Adaptation Section.

Koko Warner

Cities, climate change, and risk

People living in growing urban centers around the world face a variety of risks today related to climate change — storms and extreme weather, sea level rise, water availability are a few of the kinds of risks to people’s lives, livelihoods, and property. When these risks materialize they can be costly. For example, Hurricane Katrina caused around $US 125 billion in the wider New Orleans area when it made landfall in August 2005. Today, we primarily manage risk through insurance. We pay in advance to receive financial protection against future uncertain and potentially larger costs. The insurance industry (and sometimes society) offers us this financial protection.

Urban ecosystems and risk management

In some cities, trees, water systems, and other ecosystem services are increasingly viewed as resources for managing risks of climate change. For example, in coastal areas in tropical zones, mangroves reduce the overall impact of storm surges, reduce coastal erosion, and other risk factors to cities. Coral reefs play a similar role of buffering strong wave action and protecting vulnerable coastal settlements. Such ecosystems provide an important source of buffering and risk reduction.

These ecosystem services are also vulnerable to damage, however. In part because of the public goods nature of ecosystem services, innovative risk management solutions have begun to think about managing risks to them like public infrastructure using tools like insurance. Such infrastructures—natural or man-made—can be insured against damage.

Urban ecosystems and insurance

Resources to protect and restore ecosystems can be generated through a variety of insurance tools, such as parametric insurance approaches (trigger-based insurance payouts happen when a parameter like rainfall or wind speed reaches a certain threshold). Such tools can be combined with early warning systems linked with special training for urban populations on reducing risk to property and life. In case of an approaching storm, affected people would receive a prior warning and by applying knowledge gained through their training, secure their belongings effectively and relocate to a safe area. This scenario would reduce the overall damage to their livelihoods, while ensuring their eligibility for a payout if the storm crossed the predefined thresholds.

Especially in the case of ecosystem services in urban areas, the underlying risk can be ameliorated if the provision of such services is managed comprehensively. For example, in dense low-lying delta regions such as the Mekong Delta that are flood prone, insurance against damages caused by flooding is crucial. However, this insurance must operate hand in hand with the development of more climate resilient infrastructure, the application of building codes, or zoning regulations and other forms of adaptive planning that reduce the potential damage as much as possible.

The insurers we talk to emphasize the importance of risk reduction. By already reducing your risk through early warning systems and climate proofing infrastructure, you can better withstand the medium-frequency impacts and still get a payout from insurance in cases where damage exceeds what individuals can cope with. Some insurers even apply clauses in their policies that require insurance holders to exercise risk reduction. This way, a track record of effective risk reduction action could also lead to a reduction of insurance premiums in the long run. Our research shows that it’s not enough for people to just receive payouts; rather, the support they receive needs to be more holistic for them to be resilient in the face of climate change and other challenges.

Insurance basics. How does one best approach risks of different magnitudes and frequencies? The very frequent and less severe risks (25 years). These risks can only be addressed through insurance and other forms of risk transfer because they usually far exceed the coping capacities of the individuals at risk. However, insurance alone is not enough.

In the case of extreme but infrequently occurring risks, insurance approaches that are organized as public-private-partnerships, such as an insurance solution connected to a social safety net programme, might be able to provide better and more comprehensive protection. Such a solution would combine the strengths of all actors and divide the risks among many stakeholders. However, the important issue to keep in mind is to always link whatever insurance approach is selected to a comprehensive risk management approach.

Using financing tools to improve urban resilience: Yes

Covering the risk through insurance: Why not. But at one condition: this should be done within a broad approach not detrimental to adaptation vs mitigation.

Great minds with great thoughts which are fundamental in unlocking our thinking about urban ecosystem sustainability and climate change risk insurance.

Thank you for a thought provoking read that shows the multitude of issues surrounding valuing urban ecosystems services and who/what is the responsible entity for mitigating the risk to climate related disasters.

we need insurance to partner with govt to address coastal retreat