I have recently started working on a new project that will explore how reconnecting people with nature can help transform society towards sustainability (see http://leveragepoints.org). ‘Connectedness with nature’ has recently become a buzz phrase, with scientists, journalists and practitioners talking about the problems of disconnection, the benefits of reconnection, and the ways that we can become more connected with nature in our day-to-day lives. (See Tim Beatley’s TNOC blog on the nature pyramid).

(1) Disconnection from nature and the broader sustainability problem

Much of the discussion has been about the implications of connectedness with nature for human health and wellbeing outcomes. And for good reason! There is a growing evidence base that highlights the substantial physical and mental health benefits of interaction with green and natural environments (Keniger et al., 2013). In fact, some experts are now arguing that health outcomes of nature exposure should be considered in terms of dose-response relationships as in traditional medical research (Shanahan et al., 2015). Yet other commentators have flagged society’s disconnection from nature as underpinning broader global environmental and sustainability problems (Folke et al., 2011). If reconnecting people with nature is key to tackling major sustainability problems, what is the role of the city? Are cities part of the problem, or central to the solution?

(2) Are cities the problem or the solution?

Urban living has been cited as a key driver of people’s disconnection from natural environments (Miller, 2005). The ‘extinction of experience’ has been said to be most acute in cities, and is increasing. Children in particular are spending less and less time outdoors engaging in nature-based activities. This disconnection has been highlighted by Richard Louv in his book “Last child in the woods” (2005). His message has struck a chord with the general public, with the book receiving much attention and popular media coverage. There has also been research showing that the time children spend indoors using electronic devices has increased over time. These indoor activities have been related to a downward trend in national park visitation (Pergams & Zaradic, 2006). Cities have even been blamed for luring tourists away from wild and natural areas. The relationship between urban lifestyles and experiential disconnection from nature has been an impetus for the burgeoning growth in urban greening movements in urban planning (e.g. the Biophilic Cities movement). According to this thinking, promoting nature experiences in urban environments is key to tackling broader environmental challenges because cities are home to most people on the planet.

While urban landscapes are generally seen as presenting significant challenges to human-nature connections, some commentators consider this disconnection from nature as being positive for environmental outcomes because it concentrates impacts in a small spatial area (e.g. ecomodernist manifesto). Indeed, while local green environments are key for urban dwellers’ experiences of the natural world, low-density cities with many green open spaces may be bad for regional biodiversity (Soga et al 2015).

Therefore, a trade-off potentially exists between cities designed for human-nature experiences and those that minimise broader environmental impacts. In order to explore whether cities are the problem or solution, it’s necessary to unpack the types of human-nature connections that may be important and how these relate to sustainability outcomes.

(3) Types of disconnection

Connection with nature can be considered as encompassing multiple dimensions. Here, I consider four dimensions of nature connection—material connections, experiential connections, cognitive/psychological connections and philosophical connections—and assess the role of cities in fostering or undermining these.

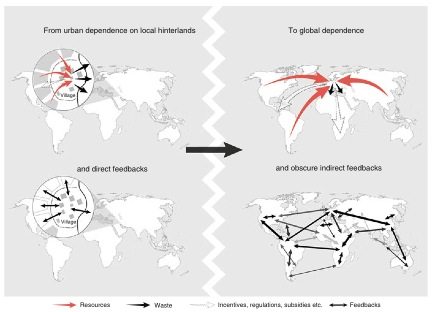

A city is defined as an area of high human population density. For this reason, cities naturally consume lots of resources, ‘metabolise’ them through various socioeconomic activities, and produce waste. This way of looking at cities is often referred to as ‘urban metabolism’. Cities are therefore hugely reliant upon (and materially connected to) natural ecosystems that provide the goods and services that sustain them. However, over the past century, cities have increased in size and number, and the nature of these connections has changed. As seen in Fig. 1, globalisation has led to cities being increasingly “tele-connected” to distant ecosystems in various parts of the globe, rather than intimately reliant upon local ecosystems that provide direct feedbacks.

As I touched on already, people’s experiential connections with urban nature characterise their day-to-day life. Experiential connections can be hampered through urban planning decisions that squeeze out green environments from the urban matrix (particularly in response to densification pressures), poor accessibility as a result of transport infrastructure (this is particularly problematic in large cities where it can be difficult to access hinterland environments), or individual behavioural decisions (often as a result of people being disinterested in nature or leading increasingly busy lives).

Cognitive connections with nature relate in part to the information people receive about their choices and behaviours. As Andersson et al. (2014) said in their recent article “[t]he physical and mental distance between urban consumers and the ecosystems supporting them mask the ecological implications of choices made”. These cognitive connections extend from knowing where food products come from through to understanding the ecology of local nature reserves. However, there’s evidence that experiential connections are related closely to environmental knowledge and psychological orientations towards the natural world. For example, a study of an urban park in Germany showed that park visitors who visited more frequently had better knowledge of animal species found in the reserve (Randler et al., 2007). In addition, research from Brisbane has shown that green space visitation rates are more greatly influenced by people’s ‘nature relatedness’ (a psychological measure of a person’s affinity with the natural world) than their proximity to a green space (Lin et al., 2014). This suggests therefore that a positive feedback may exist between people’s psychological orientation towards nature and their experience of nature: the more people experience natural environments (particularly as children), the more they will feel a connection to the natural world, and the more they will continue to visit. Conversely, the less people experience natural environments, the less they may care about them.

The final type of connection with nature might be termed ‘philosophical’ connection, or environmental worldview. Scholars are increasingly noting that different people and societies hold different perspectives on how humans relate to the natural world. The dominant philosophy underpinning modern western society is that of humans controlling nature and valuing the natural world primarily for the instrumental goods and services it can provide. This contrasts with alternative metaphors such as people as ‘stewards’ of the natural world, or as part of a broader ‘web of life’ (Raymond et al 2013). These philosophical perspectives imbue individuals, communities, and corporations and therefore have far reaching implications for sustainability. Because philosophical perspectives are passed between people within specific social contexts, cities are places where these are naturally shaped, developed and communicated.

(4) A new reconnection agenda

Cities are key to global sustainability outcomes. Urbanisation has undoubtedly contributed to the environmental crisis through the consumption of resources and disconnection of people from local environments. Yet cities are also the solution. There is a vital need to reconnect urban populations with nature, but we must also move beyond superficial connections to those connections that will contribute to systemic change. Climate change, species extinction, global poverty, natural resource depletion; these are the big issues that are facing our world today that require huge shifts in how humanity relates to the natural world. Promoting more frequent visits to the local park will not achieve this change. What we need is a wholesale shift in personal and societal orientation towards nature that results in individual and collective behaviour change.

Could focusing on connections with nature in a broader sense provide a key to the type of transformation needed? We need a reconnection agenda that focuses on reconnecting people with the natural world experientially (increased interaction with natural environments), materially (strengthening ties with local ecosystems), cognitively (increasing knowledge of our reliance on nature), and philosophically (engendering respect for the planet). As areas of high population density, cities are ideally placed to drive this reconnection agenda, particularly in regards to cognitive and philosophical reconnection. As cultural hubs, cities promote community interaction and development and ideas are spread quickly in them. Cities are also centres of economic activity and home to corporation headquarters. Institutions that may be instrumental in effecting change for sustainability are based in cities. Cities are even critical to promoting moral and religious messages related to sustainability, as highlighted by the Pope’s recent tour of the US, where he reiterated humanity’s responsibility to steward the environment. If it is value shift that’s needed, then this is most possible in cities.

So what would this reconnection agenda look like in practical terms? There is not enough space in this blog post to explore it in detail, but I present a few initial ideas here. To increase the value of experiential connections, urban planners and designers should look to enhance biodiversity in green spaces as a way of increasing the ‘intensity’ of the nature experience in what are often quite ecologically sterile landscapes (see Ikin et al., 2015, for ideas). Wellington’s ‘Zealandia’ wildlife sanctuary is a good example of a well managed and popular nature reserve close to the urban centre. In addition to this, there’s a need for cities to promote sustainability initiatives that emerge through grassroots or non-government organisations. Relevant examples include the recent ‘car free day’ in Paris, or WWF’s ‘Earth Hour City Challenge’. These initiatives can be powerful tools for generating attitudinal and behavioural change in individuals and institutions that go far beyond the single event.

Cities are key places for reconnecting people with nature. Yet it is time for cities to take nature connections to the next level: to go beyond making urban landscapes pleasant for their inhabitants to become places that drive transformation.

Chris Ives

Lüneburg

Add a Comment

Join our conversation