It is now coming to the end of the rainy season—the point in the year at which the reservoirs across Thailand should be approaching maximum storage levels in order to provide the water resources that are needed for the full range of water uses through the dry season. But as we write this blog, it is difficult to see how the next few months will unfold, and how water needs will be met.

The situation in Udon Thani in Northeast Thailand could well be particularly severe. Water levels in the main reservoir for the province have increased substantially within the last few weeks as tropical storms have moved across the country, but have only risen from 15 to 24 percent. Normally at this time of year, storage capacity should be at least 80 percent. At current levels, Udon is once again facing a major water resource crisis.

This is not the first time that such a crisis has occurred in Udon Thani. Recent years have seen more variable and unpredictable patterns of rainfall that pose monumental challenges for the various institutions with responsibility for water supply and distribution, as well as for the farmers, households, and industries that depend on regular water supply. Udon Thani exemplifies many of the problems of climate change and water resources; a changing agricultural landscape alongside urban development; and the political, technical, and institutional challenges of dealing with greater uncertainty and heightened risk.

Once again, places like Udon Thani, with ambitions to take advantage of regional economic integration, appear to be threatened by the combination of climate uncertainty and weaknesses in governance and planning.

The experience of Udon Thani illustrates the importance of governance institutions and processes that can better accommodate changing patterns of uncertainty and risk and the dynamics of an urbanizing region. But building the kinds of adaptive, learning-oriented institutions that can cope with uncertainty and risk is a major challenge. In many ways, these kinds of calls for institutional change do not fit easily with the ways that bureaucracies operate. Yet, through a combination of engaging citizen scientists and opening space for informed public dialogue, local stakeholders have begun to put the challenges of a climate resilient urban future on the policy agenda, and have begun taking actions to reimagine their urban visions.

Urbanization of Udon Thani

Part of the problem lies in the history of urbanization that Udon Thani has experienced. As the city has expanded, demand for water has increased, while precipitation has become more variable and less predictable. The city is now facing problems with water availability and quality. The city is dependent on one main water source—the Houay Louang reservoir—that was built over 40 years ago and designed to meet the largely rural irrigation needs of small-scale rice farmers. The reservoir has a capacity of 135 million cubic meters, but agriculture requires 138 cubic metres per year, and the combined demand from urban areas and industry is already at 22 million cubic metres per year.

The pressures on the Huay Luang have intensified, with the expansion of irrigated rice and other crops across the province and increasing need to meet domestic water demands of the growing urban population. This demand is only set to rise again as urban populations increase further and as industry becomes more established in the area. Udon Thani is well situated in the Greater Mekong Subregion and is positioning itself as a gateway for trade and commerce with expectations of doubling population and urbanized area within the next decade. This also involves building a second ringroad around the city to accommodate the growth in road traffic that has already occurred and that is anticipated to increase further. Public transport is limited, and there are few efforts to address public transport other than through the expansion of the road network. Future climate concerns are distant thoughts in current planning.

As the urbanized area expands there are growing pressures on land and water resources. Udon Thani has one of the highest rates of land price increase in the country. As with other parts of Thailand, much of the land that is targeted for expansion is low value land that offers the highest returns on speculation and conversion. Much of this land is agricultural or public wetland areas. While such land conversion generates enormous profits that might be hard to resist, the implications for the broader waterscape are significant.

The large wetland of Nong Dae ling to the north of the city on the road to Lao border encapsulates many of these threats and challenges. The 900 rai (355 acres) wetland has been targeted for a series of public and private developments. The natural drainage streams and canals have been much reduced in size and capacity as the road system has expanded, and as warehouses and shopping centres have been built along the highway. Private housing estates have been built on its edges—close to the main road—and are already impacting drainage and flood patterns. Additionally, state plans to fill in 90 percent of the wetland and use the site for an international convention hall, a sports hall, and as parking space for the planned nearby high-speed railway station pose even greater threats.

As well as the threats to natural storage and drainage, demand has increased as water availability has become more variable. Recent conditions appear to be consistent with climate projections that suggest dry seasons will become longer and drier, with precipitation in the rainy season becoming less predictable, and with more intense rainfall falling, often in a shorter space of time. These shifts in precipitation also raise the risk of flooding, which has been further compounded by the expansion of built-up areas across natural floodplains that in turn have altered the natural hydrology.

Recent years have demonstrated the increasing variability in rainfall from year to year, and the cumulative impacts across the years. In 2011, the main pressure on water managers was to manage the dramatic floods that affected many parts of the country. In 2012, reservoir managers released water several times during the rainy season to avoid repeating the 2011 flood crisis. By the release of water meant that at the end of 2012, as they moved into the dry season, Udon was facing a severe water shortage.

In 2013, the main pressure on reservoir managers was to ensure that the reservoir reached sufficient capacity to meet dry season demand. Early in the rainy season, the reservoir had already reached 70 percent of storage capacity when a tropical storm and the threat of intense rainfall moved towards Udon. This led the central department in Bangkok to order pre-emptive release from the reservoir to avoid the risk of flooding downstream of the reservoir and in the city. However, the storm passed without any rainfall, leaving the reservoir well below capacity. It was again a matter of luck that a subsequent but unexpected storm did actually pass through Udon with enough rainfall to refill the reservoir. Even so, in 2014, due to water shortages in the dry season, there were restrictions on allocation of water for irrigation. The levels in the reservoir dropped so low that the Royal Irrigation Department (RID) was obliged to pump the water out of the reservoir to the outflow canals. Fortunately, domestic water supply to the city could be maintained, but at a cost borne by farmers requiring irrigation. After such an intense dry season, RID reservoir managers were keen to ensure that they were able to store enough water in the rainy season to meet the demand of the following dry season.

This year has been even more problematic. With the influence of El Niño, the dry season has been far longer and drier than previously, and rainfall in the rainy season has been far lower than expected. At the beginning of September, when storage is expected to be 80 percent, the reservoir was only at 15 percent of capacity. Precipitation patterns are also proving less reliable than historical trends, making it all the more difficult for reservoir managers to plan when to store and release water.

Facing the challenge of urbanization and climate change

The main challenge has been in putting these issues on the political agenda. Despite a history of increased urbanization and despite reaching the status of a Newly Industrialized Country (NIC) in 1988, Thailand still does not have an effective national strategy or policy framework for urban development. Land use planning has been notoriously weak.

These weaknesses were revealed in glaring detail in the 2011 floods that struck most of the country, but that caused devastation in the Chao Praya basin and Bangkok. Many parts of the basin around Bangkok had been built-up from the early 1990s—agricultural land and land designated as floodways according to earlier land use plans was converted to industrial parks and housing estates with a network of roads cutting across the landscape. The flood risk was certainly well known, but was ignored as the color-coding of land use plans was changed to accommodate commercial interests. The international airport that opened in 2005 is located in King Cobra Swamp—a low-lying wetland area that provides drainage for a city that is built in the delta. As the floods approached Bangkok, there was a desperate attempt to divert the water from its natural flow as it targeted critical economic infrastructure and to steer it towards areas that would not normally flood. After the floods receded, the pressure was on to put floodwalls in place to protect industrial parks, to build walls higher, thereby shifting flood risk elsewhere. The lessons of this experience do not appear to have been learned.

The experience in Bangkok and the Chao Praya basin brought the risks home in other parts of the country. In Udon Thani, local stakeholders are assessing options for managing local water sources. The expansion of the urban area is leading to encroachment and degradation of local water bodies that have traditionally been sources for domestic water supply and that provide important drainage for the city.

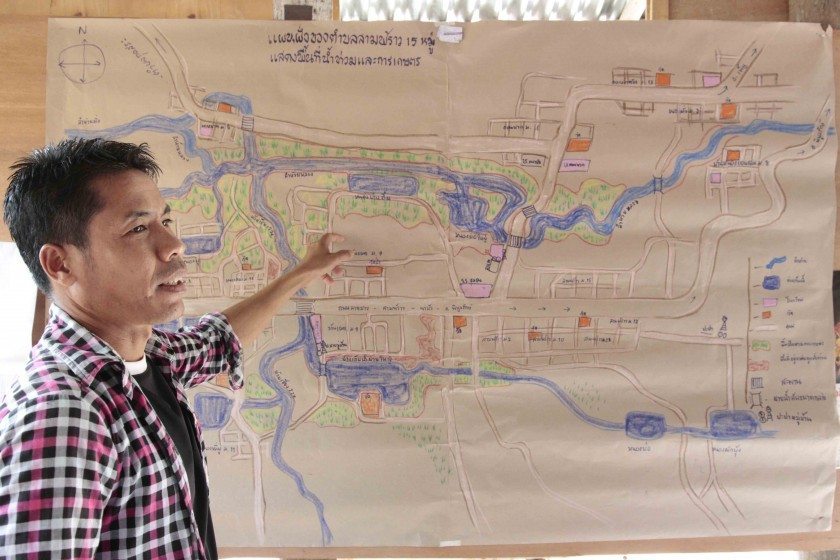

Collaborations between ISET, Thailand Environment Institute, the Municipality of Udon Thani, the local Rajabhat University, and the Thai Research Fund (TRF), along with local people across 18 villages, led to participatory action research, mapping, and assessing local water systems—including the flow, areas of flood risk—and identifying the water bodies and wetlands that contribute to urban flood drainage and provide domestic water sources. Traditionally these water bodies provided domestic water (and some irrigation) to local rural communities. However, with limited state funds, these have often been poorly maintained, leading to declines in water quality. At the same time, as the city area has expanded, these formerly rural communities are more directly linked to the urban areas. Many of these small water bodies are being targeted as sites for development of housing estates, often with wastewater discharged from the estates directly into these waterways without adequate treatment. The combination of these pressures has further reduced the water quality. With poor and unreliable water quality, the demand for water from these sources declines, pushing demand towards the piped sources from the Houay Louang.

Participatory research has pointed to options for rehabilitating and maintaining these bodies in ways that would improve natural drainage for all of the expanding urban areas, as well as providing additional water sources in a more decentralized, modular water supply, thus contributing to the flexibility, diversity, and redundancy of the urban water systems. By bringing different communities across the basin together, this research has built up a more holistic understanding of the broader landscape, and also created a platform for learning and dialogue.

Alongside this citizen science, a partnership with the Institute for Water Resources (IWR) of the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) has helped introduce shared vision planning: the application of scenario-based models to shared learning dialogues. Through a participatory process, local stakeholders have developed their own scenario-based models that consider the implications of different development and land use scenarios and analyze their implications. This tool has helped bring different stakeholders to the dialogue table and to consider specific actions. One of the core challenges with urbanization in Thailand is the need for different administrative organizations in the urbanizing area to collaborate on plans for land use and water resource management. This is largely an institutional challenge—there are few incentives for local administrations to contribute their own budgets or to place restrictions on their development ambitions. It is also a technical challenge—there are limited tools to assist the analysis of future development scenarios and options.

An additional challenge is being able to imagine an urban future that might be different from the experience of other large cities, and that might be able to steer Udon Thani away from current trajectories of urbanization. While people in Udon Thani frequently remark that they do not want their city to be like Bangkok, much of the development that is occurring is merely repeating Bangkok’s history. Poor land use planning and investment creates a path dependency; once critical economic assets are located in hazardous locations, the only way out seems to be through further construction of flood defenses that shift flood risk, and ultimately exacerbate the problem further.

With support from local and international architects, Udon Thani has been considering immediate steps to redesign their urbanizing future by establishing green infrastructure that could take advantage of natural wetlands and water bodies. With an interest in promoting bicycling as a viable transport option, there is also the potential for rehabilitating the networks of canals in the urbanizing area as both waterways and cycle paths, addressing some of the region’s water management and transport challenges.

Udon Thani is currently dependent on infrastructure built over 40 years ago and designed for different needs and for a different climate regime. The institutions responsible for policy, planning, and management are similarly structured for different challenges; they are less able to cope with emerging uncertainty and risk, or the need to operate across administrative boundaries. This kind of partnership between citizens, research centres, and government agencies, in which they take the lead in assessing and mapping water sources, is important for the information that it generates. Additionally, such a collaborative research process that involves both citizen and expert-led science contributes to opening arenas for more broadly informed public policy dialogue. These processes lie at the heart of building resilience—creating new arenas for the state and its citizens to enter into informed public dialogues to assess vulnerability and to identify innovative options for action. At the heart of this is the need for reimagining an urban future.

Richard Friend & Pakamas Thinphanga

Bangkok

Acknowledgements: This article has been prepared with funding under the IDRC/SSHRC Urban Climate Resilience in Southeast Asia (UCRSEA) partnership, an action-research and capacity building program that operates in Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam.

The original action research in Udon Thani was part of the Mekong-Building Climate Resilience in Asian Cities (M-BRACE). M-BRACE is a four–year program funded by USAID that aimed to strengthen the capacity of stakeholders in medium-sized cities in the Thailand and Vietnam region to deal with the challenges of urbanization and climate change. The program was implemented by ISET-International, in partnership with the Thailand Environment Institute and Vietnam’s National Institute for Science and Technology Policy and Strategy Studies. This blog article draws on original research being conducted under the M-BRACE program led by Dr. Santipab Siriwattanapiboon (Rajabhat University, Udon Thani) and Ms. Pattcharin Chairob (Thai Research Fund), as well as the M-BRACE Vulnerability Assessments.

about the writer

Pakamas Thinphanga

Pakamas has a technical background in biological sciences and coastal ecology with a Ph.D. from James Cook University, Australia and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Oxford. She joined TEI in late 2008.

Leave a Reply