[The Right to the City is] the right to change ourselves, by changing the city. —David Harvey, 2008

The cities we have

The cities we have in the world today are far from being places of justice. Whether in the South, the North, the West or the East, the cities we are living in are a clear expression of the increasing inequalities and violence from which our societies suffer, as a direct result of putting capital gains and economic calculations—greed!—before people and nature´s well being, dignity, needs and rights.

Many governments have abandoned their responsibility for any urban-territorial planning, leaving “the market” to freely operate the private appropriation of urban spaces.

The conditions and rules currently present in our societies are globally condemning more than half of the world population to live in poverty. The inequalities are increasing both in so-called developed and developing countries. What real opportunities are we giving to young people if, according to the UN, 85 percent of the new jobs at the global level are created in the “informal” economy?

At the same time, the spatial segregation of the social groups, the lack of access to adequate housing and basic urban services and infrastructure, as well as many of the current housing policies in different countries, are creating the material and symbolic conditions for the reproduction of the marginalization and disadvantages of the majorities. Impoverished neighborhoods (“urban slums”) are home of to at least one third of the population in the global South—in most African and some Latin American and South Asian countries it reaches as high as 60 percent or more, including the Central African Republic, Chad, Niger, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Somalia, Benin, Mali, Haiti and Bangladesh. Not having a place to live and not having a recognized address also results in the denial of other economic, social, cultural and political rights (education, health, work, right to vote and participate, among many others). What kind of citizens and democracy are we producing in these divided cities?

It is not news to anyone that, especially during the past 25 years, many governments have abandoned their responsibility for any urban-territorial planning, leaving “the market” to freely operate the private appropriation of urban spaces, almost without any restriction to real-estate speculation and the creation of exponential revenues. It does not require expertise to realize that almost everywhere land prices have grown hundreds of times while minimum wages have remained more or less the same, making adequate housing unaffordable for the vast majority of the population.

The Cities We Want: Right to the City and Social Justice for All

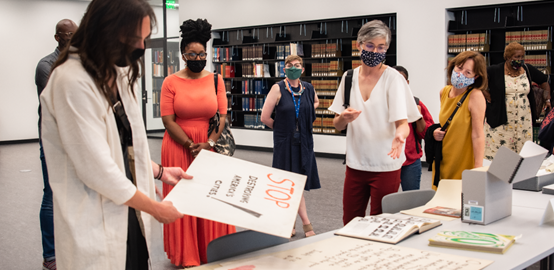

At the occasion of the World Habitat Day commemoration in October 2000, more than 350 delegates of urban social movements, community based women and indigenous people organizations, tenants and cooperative housing federations, and human rights activists from 35 countries around the world got together in the great Mexico Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) over an entire week to exchange concrete experiences and build proposals for more inclusive, democratic, sustainable, productive, educative, safe, healthy and culturally diverse cities.

Under The City We Dream motto, this first World Assembly of Inhabitants produced what would become one of the pillars for the elaboration of the World Charter for the Right to the City, a process developed inside the World Social Forum between 2003 and 2005. For the past decade, that document has inspired several similar debates and other collective documents of the city we want, as the Mexico City Charter for the Right to the City (2010), not as simple wishing list but as a clear roadmap on how to achieve it. Many of those are now included in political and legal instruments signed by local and national governments, as well as some international institutions.

Based on that foundation, the Just City for an Urban Century must be based on the six strategic principles of the Right to the City:

- Full exercise of human rights in the city

A just city is one in which all persons (regardless of gender, age, economic and legal status, ethnic group, religious or political affiliation, sexual orientation, place in the city, or any other such factor) enjoy and realize all economic, social, cultural, civic and political human rights and fundamental freedoms, through the construction of conditions of individual and collective wellbeing with dignity, equity and social justice.

Although universal as they are, provisions should be taken to prioritize those individuals and communities living under vulnerable conditions and with special needs, such as homeless, people with physical disabilities or mental and chronic health conditions, poor single parents, refugees, migrants, and people living in disaster-prone areas.

As duty holders, national, provincial and local governments must define legal frameworks, public policies and other administrative and judicial measures to respect, protect and guarantee those rights, under the principles of allocating the maximum available resources and non-retrogression, according to human rights commitments as included in international legal instruments.

Cities around the world, like Rosario in Argentina, Graz in Austria, Edmonton in Canada, Nagpur in India, Thies in Senegal and Gwangju in South Korea, among several others, have declared themselves as Human Rights Cities, going beyond specific human rights programs to try to instill a human rights framework in the city daily life and institutions. Of course they face many contradictions and challenges, but they also represent a concrete path for other cities to consider.

- The social function of the city, of land and of property

A just city is one that assures that the distribution of territory and the rules governing its use can thereby guarantee equitable use of the goods, services and opportunities that the city offers. In other words, a city in which collectively defined public interest is prioritized, guaranteeing a socially just and environmentally balanced use of the territory.

Planning, legal and fiscal regulations should be put in place with the required social control, in order to avoid speculation and gentrification processes, both in the central areas as well as in peripheral zones. This would include progressive increase of property taxes for underutilized or vacant units/plots; compulsory orders for construction, urbanization and priority land use; plus-value capture; expropriation for creation of special social interest and cultural zones (especially to protect low-income and disadvantaged families and communities); concession of special use for social housing purposes; adverse possession (usucapio) and regularization of self-built neighborhoods (in terms of land tenure and provision of basic services and infrastructure), among many others already available instruments in different cities and countries, like Brazil, Colombia, France and the United States, just to mention a few.

- Democratic management of the city

A just city is one in which its inhabitants participate in all decision-making spaces to the highest level of public policy formulation and implementation, as well as in the planning, public budget formulation, and control of urban processes. It refers to the strengthening of institutionalized decision-making (not only citizen consultancy) spaces, from which it is possible to do follow-up, screening, evaluation and reorientation of public policies.

This will include participatory budgeting experiences (being used in more than 3,000 cities around the world, with some important examples like Dominican Republic, Peru and Polonia), neighborhood impact evaluation (especially of social and economic effects of public and private projects and megaprojects, including the participation of the affected communities at every step of the process) and participatory planning (including master plans, territorial and urban development plans, urban mobility plans, etc.).

Several other concrete tools are already being used in many cities, from free and democratic elections, citizen audits, popular/civil society planning and legislative initiatives (including regulations around granting, modification, suspension and revocation of urban license) and recall election and referendums; to neighborhood and community-based commissions, public hearings, roundtables and participatory decision-making councils.

Nevertheless, several countries—specially in the Middle East and the South Asian region—still have strong, centralized, and in many cases non-democratic national governments, that appoint local authorities and hinder more participatory decision-making process to happen.

- Democratic production of the city and in the city

A just city is one in which the productive capacity of its inhabitants is recovered and reinforced, in particular that of the low-income and marginalized sectors, fomenting and supporting social production of habitat and the development of social and solidarity economic activities. It concerns the right to produce the city, but also the right to a habitat that is productive for all, in the sense that generates income for the families and communities and strengthen the popular economy, not just the increasingly monopolistic profits of the few.

It is known that in the Global South between half and two thirds of the available living space is the result of people’s own initiatives and efforts, with little, if any, support from governments and other actors. In many cases, these initiatives go against many official barriers. Instead of supporting those popular processes, many current regulations ignore, or even criminalize, people’s individual and collective efforts to obtain a decent place to live.

At present, few countries—namely Uruguay, Brazil and Mexico—have put in place a system of legal, financial and administrative mechanisms in order to fully support what we call the “social production of habitat” (including access to urban land, credits and subsidies, and technical assistance); but even there, the percentage of the budget that goes to the private sector remains above the 90%, for the construction of “social housing” that remains unaffordable for more than half of the population.

- Sustainable and responsible management of the commons (natural and energy resources, as well as cultural patrimony and historic heritage) of the city and its surrounding areas

A just city is one whose inhabitants and authorities guarantee a responsible living relationship with the nature, in a way that makes possible a dignified life for all individuals, families and communities, in equality of conditions but without affecting natural areas and ecological reserves, cultural and historic patrimony, other cities or the future generations.

Human life and life in urban settings is only possible if we preserve all forms of life, everywhere. The urban life takes a vast diversity of the resources it needs from outside the formal administrative boundaries of the cities. Metropolitan areas, regions that include smaller towns in the countryside, agricultural and rural areas, and rain forest are all affected by our urban behavior.

There is an urgent need to put in place more strict environmental regulations and use of appropriate technology at an affordable cost, promote aquifer protection and rain-water collection; to prioritize multimodal public and massive transportation systems; to guarantee ecological food production and responsible consumption, notably including reuse, recycling and final disposal; among several other urgent measures.

- Democratic and equitable enjoyment of the city

A just city is one that reinforces social coexistence, through the recovery, expansion and improvement of public spaces, and its use for community gathering, leisure, and creativity as well as critical expression of political ideas and positions. In recent years, and especially as a local and spatial consequence of the neoliberal policies, a great part of those spaces that are fundamental in the definition of the urban and community life have not been taken care of, have been abandoned or left in disuse or, worse yet, have been privatized: streets, plazas, parks, forums, multiple-use halls, cultural centers, etc.

Infrastructure and programs to support cultural and recreational initiatives, especially, those that are autonomous and self-managed with strong participation of youth, low-income sectors and minority populations are needed. In short, public policies must guarantee the city as an open space and as an expression of diversity.

* * *

In an urban century, the meaning of justice will necessarily include all the dimensions of social life: political, economic, cultural, spatial (territorial) and environmental. The just city of the new century will be a city in which the decision making processes are not monopolized by few “representatives” and political parties, but are in the hands of the communities and the citizens; the land, the infrastructure, the facilities and the public and private resources are distributed for social use and enjoyment; the city is recognized as a result of the productive contributions of the different actors and the goal of the economic activities is the collective wellbeing; all human rights are respected, protected and guaranteed for everyone; and we conceive ourselves as part of nature, and nature as something sacred that we all should take care of.

In an urban century, the just city would be the result of, and at the same time the condition for, a just society on a healthy planet.

Lorena Zárate

Mexico City

The Just City Essays is a joint project of The J. Max Bond Center, Next City and The Nature of Cities. © 2015 All rights are reserved.

Leave a Reply