On the flipside you can do anything (…) the flipside bring a second wind to change your world. Encrypted recipes to reconfigure easily the mess we made on world, side B —Song ‘Flipside’, written by Nitin Sawhney and S. Duncan

My brainstorming for this essay started thinking about the comprehensive list that follows the affirmation of “a just city is a city that…” But my brain fell to the temptation of looking at the task from the reverse angle. What are the key ingredients of the perfect recipe for the mess of injustice in a city?

The main point I would like to make is that frameworks, spatial planning, management financing and governance are essential foundations and enablers for a multidimensional conception of justice in a city. Why? Because justice in a city is about social, political, economic and environmental justice. Once more, why these enablers? Because not only they can, but actually in many cases will, deliver better results if conceived and operationalized with the city-region scale as their wider framework. Justice in a city goes beyond its administrative boundaries. Ultimately a city will not be just if it is triggering injustice in the peri-urban or metropolitan areas or the wider region it relates to.

Frameworks, spatial planning and management

Today cities are home to half of the world’s population and three quarters of its economic output, and these figures will rise dramatically over the next couple of decades. Urban development, with its power to trigger transformative change, can and must be at the front line of human development.

We seem to forget, though, that urban development is a complex process. It is a social process, and one that develops over time. To avoid getting trapped in morally abhorrent injustice, it is about time we collectively realize that urban development, like any other complex social process, needs to be soundly and sufficiently framed, planned and managed. City and regional spatial planning—territorial planning—can be an essential enabler of justice.

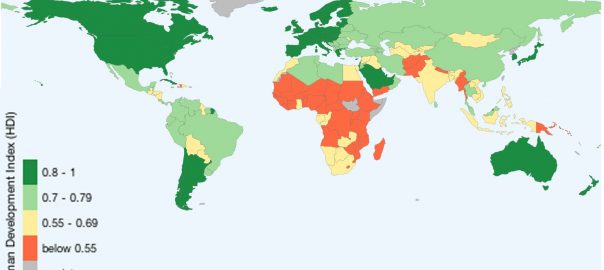

The majority of population growth in cities is the result of natural increase, rural-urban migration and the reclassification of formerly non-urban areas. It is also predominantly taking place in cities in developing countries, most notably in Africa and Asia. In many areas of the world, cities tend to endlessly sprawl, consuming the periphery land and, ultimately, nullifying the social, economic and environmental advantages of agglomeration. Spatial planning at the city-region scale can achieve balanced territorial development. It can promote mutually reinforcing urban and rural development and hence control and correct scenarios where cities trigger injustice in the peri-urban or metropolitan areas or the wider region they relate to.

Spontaneous proliferation concludes in forcing and segregating the most deprived and those facing vulnerability; those too often trapped in a life of morally unacceptable slum-like conditions. Spatial planning and urban design for the just city can secure a grid that enables food systems across the rural urban continuum and that provides access to affordable, safe and sustainable housing, water and sanitation, energy, waste management and mobility. In case these were not enough elements of justice, let us not forget their inextricable links with human and environmental health, prosperity and socio-economic development, community resilience, and, ultimately, respect for human rights.

Statistics show that in unplanned cities, public green space and publicly accessible open space virtually disappear. Gone with these public spaces are their benefits for social cohesion, equality, intercultural and intergenerational exchange, healthy lives and environmental sustainability—aspects inextricably linked to a multidimensional notion of justice. Spatial planning and urban design can offer solutions to fix this; solutions that can be exponentially empowered with strategies and norms to regulate the private ownership of land.

In a global sample of 120 cities, the sum of all urban areas that are not covered by impervious surfaces was estimated between 30 percent to almost half. Out of the 40 cities studied by UN-Habitat, only 7 allocated more than 20 percent of land to streets in their city core, and less than 10 percent in their suburban areas. In Europe and North America the cores of cities have 25% of land allocated to streets, whilst suburban areas have less than 15%. In most city cores of the developing world, less than 15% of land is allocated to streets and the situation is even worse in the suburbs and informal settlements where less than 10 percent of land is allocated to street. This is a reflection of the huge inequalities in many cities of the developing world. Over the last 30 years, public spaces are becoming highly commercialized and have been replaced by private or semi-public buildings. Commercialization divides society and eventually separates people into different social classes.

The United Nations programme for cities and human settlements, UN-Habitat is proposing a set of targets for the amount of land allocated to streets and public space in urban areas to ensure adequate foundation for the city. It is proposed that 45 percent of land should be allocated to streets and public space. The World Health Organisation recommends a minimum of 9 square meters green space per capita and that all residents live a 15-minute walk to green space.

Cities in their socio-cultural, economic and environmental complexity contain systems — cities are systems of systems. For far too long, urban development has been predominantly dominated by silo thinking and action. This has resulted in the aggravation of interconnected challenges leading to injustice in cities, including running against environmental sustainability and its notion of planetary boundaries. An integrated and systems-based management for our cities can take us very far in correcting and preventing the socio-economic and environmental injustice many cities face.

On the positive side, several pioneer cities across the globe have make proof of political and technical commitment to find planning and management solutions for sustainability in its three dimensions: social, economic and environmental. For the curious reader, I would vividly recommend taking a look at the inspirational collection of case studies that the network ICLEI Local Governments for Sustainability has recently compiled. This collection of case studies sees the light on the occasion of the historic adoption of the global 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs, including the unprecedented SDG11 to “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable in the horizon of 2030.”

Important examples include the integral urban development project of Medellín (Colombia); the district energy pilot project in Rakjot (India); the framework for uniting municipalities around a regional food system in Vancouver (Canada); the actions to turn trash into food in Mexico City (Mexico); the integrated moves to tackle city growth traps in Dongguan (China); the “Ecological Capital” approach in Curitiba (Brazil) as a world renowned model for innovative integrated planning and management; the strategies for protecting a world treasure of biodiversity from urban pressures in Cape Town (Africa); or the multi-annual efforts in Bristol (UK) to win the European Green Capital Award. All these and many more are examples of real tools and approaches to commit to sustainable urban development and rip its benefits for social, political, economic and environmental justice.

A last but not least crucial point needs to be highlighted. Spatial planning at the city-region scale, as well as integrated and systems-based city management are indeed answers for reconfiguring the mess of injustice in cities. However, this does not equal leaving it all to the sole action by the city or the regional levels. Achieving just cities will require strong action by governments and policymakers at all levels. Strategic frameworks and plans at the national level are a 21st-century must-have in order to achieve social, political, economic and environmental justice in a city and beyond its administrative boundaries. National urban policies, adapted to the needs and assets of a country, its regions and cities, and crafted by close collaboration among all levels of government, must be incentivized by international frameworks and implemented at the national level. With 70 percent of global population projected to live in cities by 2050, it is profoundly disconcerting that only around 30 countries have national urban policies.

Financing

Local and regional/state governments across the globe are regularly responsible for the provision of housing, public services and utilities, among other important services and tasks for justice in a city. Besides, many cities face the costly struggle of adapting to increased vulnerability to climate change and natural disasters. All this while they can no longer afford the cost of updating infrastructural backlogs. Around the globe, it can be said that on average the revenue and expenditure share of local and regional/state authorities is not commensurate with the strenuous financial burden these three realities impose on them. In this predominant context of inadequate financing the ability of local and regional/state governments to effectively combat poverty and inequality is reduced.

The highly political question of mobilisation of resources for and at the local level is also an issue of justice in the city. It cannot be left only to local and regional/state governments because the prevailing models for financing and for access to financing across the globe are leaving them hand-cuffed. International and national frameworks must change course to empower and enable new models for financing local and regional/state governments, as well as to open further access to financing for them.

Perhaps we could dream of a break-through in this political impasse, if the international financial institutions, the multilateral organisations and national governments could assess this question from the perspective of socio-economic and environmental justice for people and their communities. Enablers to reconfigure the mess exist, can be incentivized by international frameworks and operationalized with sustained dialogue among all levels of government.

Updating the level of national transfers and/or authority to generate additional income through taxes, as well as non-tax mechanisms will enable improvements. Local and state/regional governments need to be empowered to raise local revenue and tap local resources, while linking revenue enhancement with service delivery and transparency. Strengthening municipal finance is key for these levels of government to become credit worthy and access external financing.

There are other enablers to reconfigure the mess and enable the mobilisation of more resources for local and state/regional governments to invest in social, political, economic and environmental justice programmes. Improving the capacity of these levels of governments to capture land value is one. Another example is implementing frameworks for their access to capital markets. A third enabler is strengthening their capacity in areas of bankable infrastructure project development, land-based financing, and access to municipal development banks and/or pooled municipal financing. The set up of city and regional investment funds, combined with green growth funding and social enterprise funds, for instance, can also support justice objectives. Last but not least, participatory budgeting can provide a collectively owned framework for investment in multidimensional justice at the neighbourhood and city scale.

Governance

For me, governance and justice in a city are two sides of the same coin. The list of enablers to reconfigure the mess of injustice here is so naturally long, that it would be impossible for me to honour it in the space provided for this essay. Different words may be used, but I would like to believe that those who share my passion for urban and territorial development for their people and by their people would agree that governance is the lifeblood of a just city.

There are two obvious and fundamental enablers to reconfigure the mess: the empowerment of healthy democracies at all levels of governments, as well as of decentralisation in respect of the principle of subsidiarity. The principle of subsidiarity indicates that matters ought to be handled by the smallest, lowest or least centralized competent authority. Political decisions should be taken at a local level if possible and more efficient, rather than by a central authority. I am saying that these are obvious and fundamental enablers; not that they are easy in the current state of world affairs.

Other enablers to reconfigure the mess of injustice in a city that I would like to focus on relate to the critical decisions that will be taken at the United Nations within 2016. These decisions will operationalize the universal 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals—including SDG11’s “Make cities and human settlements safe, inclusive, resilient and sustainable.” Moreover, in 2016 urban development leaders will be adopting the “New Urban Agenda” for the next 20 years at the Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development Habitat.

Indicators that will assess progress against goals and targets will be crafted. Monitoring and review systems will also see the light of the day. Justice in cities calls for data collection that provides the basis for disaggregation down to the micro-level, to the neighbourhood level. Situations of social, economic, political and environmental injustice in cities cannot go hidden behind national averages.

Grass-roots data collection systems and citizen-generated data, involving directly the urban poor and other disadvantaged groups should underpin monitoring systems. Data should be legitimated via institutionalized arrangements between regional and local governments and the experts collecting it and should focus on identifying community-driven priorities, with particular attention to the needs of those living in vulnerable situations and of the urban poor. Moreover, data should remain publicly available and accessible to all citizens and communities.

An inspiring ongoing initiative of grass-roots data collection is the project of Shack/Slum Dwellers International with the Ghana Federation of the Urban Poor (GHAFUP) for profiling Accra’s slums, which builds upon several previous projects carried out in other countries.

Transparent, inclusive and participatory accountability and review systems from the international to the local levels are non-negotiable and constitute enablers to reconfigure the mess of injustice in cities and beyond cities.

Multi-stakeholder partnerships for the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, for the implementation of each SDG and for the “New Urban Agenda,” if well managed, will be powerful enablers to reconfigure, re-invent and imagine. The frameworks for these partnerships at all levels must ensure the engagement and participation of civil society and all relevant stakeholders. They should also build capacity in all levels of governments for fair, transparent and human-rights anchored public private partnerships, which are central to the provision of public services and utilities to urban dwellers.

All these enablers to reconfigure the mess of injustice we have made on the side B of our cities are not exempt of complexity, political cost, innovation and bravery. Just sustainable urban development is not an easy task but my arguments above show that we have tools and approaches to plan it, manage it, fund it, govern it and achieve it. As humankind, over the centuries and the different civilizations we have found solutions to evolution challenges.

We learned to make fire. We invented the wheel, the steam engine and the airplane. We discovered penicillin. We get a bit further in outer space every year. We have propelled an information technology revolution that has changed at unprecedented pace the face of what we deemed possible.

I am not ready to accept that we would let the complexities of operationalising just sustainable urban development shy us away from the moral imperative of achieving it.

Maruxa Cardama

New York

The Just City Essays is a joint project of The J. Max Bond Center, Next City and The Nature of Cities. © 2015 All rights are reserved.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation