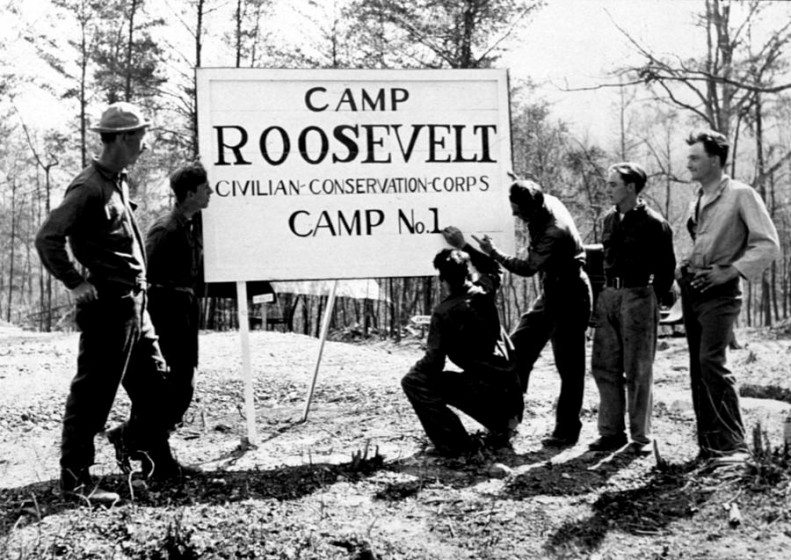

Which American president administration of the last century has the strongest record on preserving the environment and natural beauty? Presidents Theodore or Franklin Roosevelt, who created the National Wildlife Refuge System (protecting 230 million acres) and established the Civilian Conservation Corps, putting 2.5 million people to work building trails and planting trees, respectively? President Kennedy, who created the Cape Cod National Seashore? President Nixon, who signed the Clean Air Act and created the EPA? President Obama, who has led international efforts to address climate change?

Or was it the president who hosted a White House Conference on Natural Beauty, and spoke stirringly on the importance of a clean environment in his first State of the Union message?

In fact, the U.S. president with the strongest environmental track record (particularly focused on land conservation and the protection of natural beauty) is President Lyndon B. Johnson, who—alongside his activist first lady, Lady Bird Johnson—signed more than 300 conservation measures into law, establishing the legal foundations for how we protect the nation’s land, water and air.

What would President and Mrs. Johnson think now, as partisan politics and fringe political movements in the U.S. work to strip environmental legislation of its power?

Growing up in the 1960s, I found President Johnson to be a larger-than-life figure. Unfortunately, I associated him primarily with the start and the growth of the Vietnam War, a quagmire which grew deeper throughout his administration. But recently, and particularly with the 50th anniversary of his signing of the Highway Beautification Act (known derisively at first as “Lady Bird’s Law”) on October 22, my appreciation for the environmental legacy of President and first lady Johnson has deepened.

Lyndon Baines Johnson, or LBJ, was vice president under President John F. Kennedy, following a long career in Texas state politics and both houses of the U.S. Congress. He became president after Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963. He, his wife and two daughters moved into the White House soon thereafter, and he was elected president in November 1964.

President Johnson’s wife, born Claudia Alta Taylor in 1912 and nicknamed “Lady Bird” by her nanny, had spent much of her childhood in the meadows and woodlands of Karnack, Texas. She attended and graduated from both St. Mary’s College at Dallas and the University of Texas at Austin. She and the future president met and were married in 1934.

There is a lot of speculation as to why President and Lady Bird Johnson were so keenly interested in the environment and natural beauty; some think it is rooted in Mrs. Johnson’s loss of her mother at a very young age, after which she found solace in the flowers and plants around her childhood home. President Johnson—who led the passage of groundbreaking civil rights legislation and many other significant domestic policy acts of the “Great Society”—fully acknowledged his wife’s role as instigator of, and inspiration and advocate for much of his environmental legislation.

President Johnson’s environmental track record was established early. Just one year after being sworn in as president aboard Air Force One, he conveyed a strong and prescient philosophy towards the importance of a clean and improved environment in his State of the Union Address, in January 1965:

The Beauty of America

“For over three centuries the beauty of America has sustained our spirit and has enlarged our vision. We must act now to protect this heritage. In a fruitful new partnership with the States and the cities the next decade should be a conservation milestone. We must make a massive effort to save the countryside and to establish—as a green legacy for tomorrow—more large and small parks, more seashores and open spaces than have been created during any other period in our national history. A new and substantial effort must be made to landscape highways to provide places of relaxation and recreation wherever our roads run.

Within our cities imaginative programs are needed to landscape streets and to transform open areas into places of beauty and recreation.

We will seek legal power to prevent pollution of our air and water before it happens. We will step up our effort to control harmful wastes, giving first priority to the cleanup of our most contaminated rivers. We will increase research to learn much more about the control of pollution.

We hope to make the Potomac a model of beauty here in the Capital, and preserve unspoiled stretches of some of our waterways with a Wild Rivers bill.

More ideas for a beautiful America will emerge from a White House Conference on Natural Beauty which I will soon call.”

Less than two months later, at the urging of his wife and aides—including Nash Castro, White House liaison and deputy regional director of the National Capital Parks for the National Park Service—President Johnson and volunteer Chairman, Laurance S. Rockefeller, convened an unprecedented and never-imitated “White House Conference on Natural Beauty.” More than 800 people attended the two-day conference, held in late May. Castro, now 96, remembers the conference was so large they planned to hold it on the White House South Lawn. However, as Castro recalled in a recent phone interview, “the heavens opened up and we had to squeeze 800 people indoors—President Johnson stood at the door like a shepherd, herding the guests, saying ‘Come on in—hurry up.’ ”

Recently, the nonprofit organization Scenic America hosted a two-day event in Washington, heralding the accomplishments of Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson and Laurance Rockefeller. In a draft report (discussed below), they note “The Governors of 35 states subsequently [to the 1965 White House Conference] convened statewide natural beauty conferences. A wave of citizen action followed, dedicated to neighborhood improvement, protection of the countryside and preservation of historic sites.”

The conference was both preceded by and paved the way for many legislative and executive accomplishments, foremost among them the Highway Beautification Act, the Land and Water Conservation Fund (which uses offshore oil and gas leases instead of taxes as a funding source), the Clean Water Act, the Wilderness Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and many more, including the creation of 47 new national parks.

Lady Bird Johnson first became known for the beautification of Washington via the Committee for a More Beautiful Capital, which she formed in 1964 with the help of philanthropist Mary Lasker; Washington Post publisher Katherine Graham; philanthropist Brooke Astor; Assistant Secretary of State Kathleen Louchheim; architects Nathaniel Owings and Edward Durell Stone; Laurance S.Rockefeller and other donors. Castro can still recite the precise accomplishments: I million daffodils planted throughout the city; 10,000 azaleas planted on Pennsylvania Ave; 1,000 dogwoods and a large portion of the cherry trees on Hains Point (part of a total of 3,800 cherry trees planted by 1965, which compose the annual, festive cherry blossom splendor for which the capitol is now known).

Lady Bird Johnson’s best-known accomplishment may be the Highway Beautification Act, a piece of legislation her husband fought for and which was mockingly referred to by Senator Bob Dole as “Lady Bird’s Law.” Castro and others recall how President Johnson promised a dinner and reception at the State Department, featuring a cameo from actor Fredric March. Despite Republican objections, the bill was finally passed, and the Congress got their promised reception very late at night.

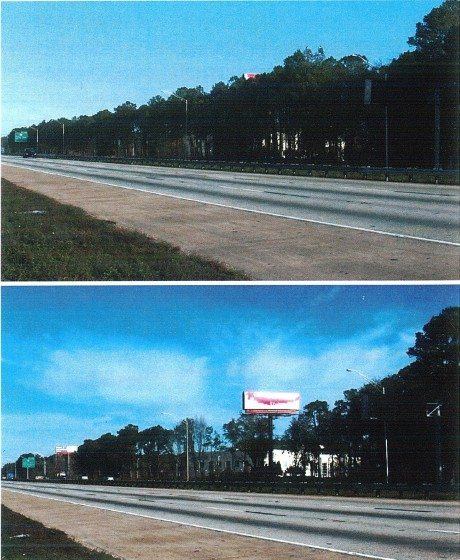

Beyond the Washington political intrigue and drama worthy of a “House of Cards” episode, the Highway Beautification Act, though watered down somewhat by the billboard industry, led to the control of outdoor advertising, the removal of certain types of signs along the interstate highways, and the removal or screening of junkyards. It also encouraged scenic enhancement, which led to the requirement that a certain percentage of federal funds on highway projects be used for planting native flowers, plants and trees. Never resting on her laurels (or her azaleas), Mrs. Johnson made forays out to the national parks across the country on at least 11 separate trips, often with Castro and the media in tow, calling attention to the need to conserve, protect and enhance natural beauty.

What drove Lady Bird Johnson in her mission to beautify an entire nation, from hardscrabble inner-city neighborhoods to vast national parks and highway systems?

Warrie Price, a very close family friend to the Johnson family (and roommate to first daughter, Lynda Johnson Robb, while they were freshmen at the University of Texas), recalls that natural beauty and plant life was “part of [Lady Bird Johnson’s] DNA as a child in Karnack…Outdoor life was her companion, partner, best friend.” According to Price, the “tragic ascension“ to the White House “put [Lady Bird Johnson] in a place where she decided that she would be a ‘doer’ nationally.” (Interestingly, Price herself went on to move to New York City from her home in San Antonio, where she also became a “doer” and led the creation of The Battery Conservancy, whose features include a spectacular perennial wild garden. Fellow San Antonians Elizabeth Barlow Rogers and Robert Hammond would create the Central Park Conservancy and Friends of the High Line—both urban repositories of great natural beauty—respectively. This prompts one to ask: What was in the water in San Antonio?

At the conclusion of the Johnson administration in 1968, the president presented his wife with a plaque adorned with 50 pens used to sign 50 laws related to natural beauty and conservation, and inscribed: “To Lady Bird, who has inspired me and millions of Americans to try to preserve our land and beautify our nation. With Love from Lyndon.”

After leaving the White House, Mrs. Johnson focused on Texas, leading the creation of a 10-mile trail around Town Lake in Austin (later renamed Lady Bird Lake) and promoting the beautification of Texas highways by awarding prizes for the best use of native Texas plants to enhance scenery. Her culminating action on behalf of nature was the creation of the National Wildflower Research Center in 1982, the year she turned 70. The Center, later moved to a new location in the Hill Country southwest of Austin, opened in 1995 as the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. The world-renowned organization, now spread across more than 279 acres, has more than 700 plant species on display and provides programs for adults and children. Alongside the American Society of Landscape Architects, the center also played a lead role in the development of the “Sustainable Sites” program, a rating system for sustainable landscape design similar to LEED for architecture.

So what would President and Mrs. Johnson think now, as partisan politics and fringe political movements work to strip environmental legislation of its power, to sell off federal lands for profit and exploitation, and to hold hostage the renewal of the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which expired in September 2015 due to Congressional inaction?

Happily and hopefully, the environmental legacy and passion for public-private partnerships between citizens and government continues to inspire citizens and nonprofit groups. On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of both the White House Conference on Natural Beauty and the Highway Beautification Act, Scenic America convened a conference and is working on a plan whose recommendations include increasing funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund; establishing a national inventory of parks and open spaces; restoring the defunct National Scenic Byways Program; undergrounding overhead wires; and enacting federal and state legislation to prohibit the removal of trees to increase billboard visibility, among many conservation-oriented action plans. Other major groups, including The Trust for Public Land and The Nature Conservancy, are working as a coalition to press Congress to reauthorize and fully fund the Land and Water Conservation Fund. And as we all travel on highways and enjoy beautiful views of fields of wildflowers, we can remember with appreciation a White House that cared passionately about native plants, vibrant parks, a clean and healthy environment, and the values of natural beauty.

Adrian Benepe

New York City

Leave a Reply