about the writer

Divya Gopal

Divya Gopal is a researcher at the Department of Ecology, TU Berlin, focussing on the role of culture in urban green spaces.

Introduction

Nature is dynamic, constantly evolving and adapting to changes. In its various forms and functions (be it plants or animals), nature is accounting for human-induced changes, reorganizing itself to form novel ecosystems. Urban spaces are distinct novel ecosystems with a mix of various green forms—cultivated ornamental exotics, spontaneous exotics, spontaneous natives, invasive weeds, hybrids and more. Irrespective of their origins, most forms of greenery are welcome in our concrete urban jungles. They seem to perform various ecosystem functions in our densely packed urban spaces.

While conservation of native species is important, is it viable, in rapidly evolving urban spaces, to insist on native purity? With increasing numbers of climate refugees, can native purity be stressed too much? Or is it better to look at green forms and functions—both native and introduced—where they assist ecosystem functioning, filling up gaps in urban ecosystems? Instead of the “good natives, bad aliens” narrative, should conservationists look only at aggressive invasives that disrupt certain ecosystem functions as bad, rather than emphasizing purity? How important is it to strictly plant native species in urban areas? Can non-natives also be welcome?

about the writer

Yolanda van Heezik

Yolanda van Heezik is currently exploring children’s connection with nature, and how ageing affects nature engagement. She is part of a multi-institutional team investigating restoration in urban areas, and cultural influences on attitudes to native biodiversity.

Yolanda van Heezik

New Zealand landscapes are dominated by introduced species, more so than in most other countries, and this is particularly evident in urban areas. In the city where I live, 44 percent of bird species are introduced, and they make up over half of the bird population. Gardens typically contain twice as many exotic as native woody species, and a significant proportion of gardens have no native plants at all. Across all gardens that we studied, 83 percent of woody species were introduced, with the most popular species being roses and rhododendrons. Dave Kendal’s work has shown that people’s preferences are strongly influenced by aesthetic traits, such as flower size and foliage colour, so it’s no surprise that the most popular native trees in NZ are those that have colourful flowers, such as kowhai and pohutakawa. We’ve asked people about their preferences for native as opposed to exotic plants and found a complete disconnect: most people say they prefer natives (40 percent) or a native/exotic mix (36 percent), but when we surveyed their gardens, these were dominated by exotics.

A significant downside of allowing introduced species to take over our environment is loss of national identity.

In my mind, a significant downside of allowing introduced species to take over our environment is loss of national identity. I am occasionally appalled by the lack of knowledge and awareness many urban residents have regarding native species. I’ve been asked if there are any native birds in our city. I’m also disappointed when I see landscaping around prominent public features dominated by exotic species. New Zealand is admired by tourists for its green, beautiful scenery, but in many landscapes that green is almost entirely exotic. I don’t think that we will ever be able to remove introduced species from urban environments, even though they are a significant source of potentially invasive species and a major cause of biotic homogenisation. However, we should be creating cities that reflect our natural heritage and that emphasise our uniqueness.

Different perspectives emerge within the social science literature. My attitude could come under fire from those that argue that a “pro-native tyranny” has developed out of a suggested link between native plant advocacy and anti-immigrant “nativism,” and that landscape professionals should not feel constrained to use native species over more attractive exotic species.

Alternatively, the value I suggest people should place in native plants might be interpreted in the context of a contemporary reaction to a history of “botanical colonization,” whereby the natural NZ landscape was replaced with an English landscape. Whatever the motivation, I believe some kind of compromise must be sought that results in a greater representation of native species in urban areas, and fosters an enhanced sense of national identity through planting and encouraging those species that are “of this place.”

about the writer

Colin Meurk

Dr Colin Meurk, ONZM, is an Associate at Manaaki Whenua, a NZ government research institute specialising in characterisation, understanding and sustainable use of terrestrial resources. He holds adjunct positions at Canterbury and Lincoln Universities. His interests are applied biogeography, ecological restoration and design, landscape dynamics, urban ecology, conservation biology, and citizen science.

Colin Meurk

The simple answer is “no”; “native purity” isn’t a realistic or viable option! It has been said that there are no “pure” indigenous ecosystems anywhere on the planet now — if you want to get down to the microbial scale. Novel ecosystems certainly predominate (often with abundant alien plants) in temperate to tropical climes. Various words to describe these systems have gone in and out of fashion — novel, recombinant, hybrid, reconciliation ecology, even “ragga-muffin.” I’ve provided a typology (Meurk 2011) for such mixed communities based on their initial condition, imposed conditions, ratio of indigenous to exotic species, and the trend in that relative balance. It defines various stages of maturity, mixing, displacement and recombination. Four broad “initial” conditions’ are remnant, spontaneous (successional), deliberative (planted), and complex (mixtures of several states).

But, what is “wild?” There is an appetite again for “rewinding” and using “cues for care” in urban environments to make this acceptable.

“Pure” ecology desires fully indigenous ecosystems. Captive, gardened plants may preserve some of the genetic story, but not their full, intrinsic potential niche — the purpose of representative, nature conservation. On the other hand, species surviving in spontaneous recombinant ecosystems, especially if responding to a range of management or disturbance regimes, may be cumulatively exhibiting their fundamental ecological niche. I call this gradient management (see Meurk & Greenup 2003). Paradoxically, at least in the idiosyncratic biogeographic context of NZ, the survival of many lowland herbaceous species may depend on creating a wide range of stressed and disturbed combinations (cf Grime) in urban environments.

But, what is “wild?” There is an appetite again for “rewinding” and using “cues for care” (Nassauer) in urban environments to make this acceptable. The niche envelopes can be as surely defined in these contrived ‘wild’ urban environments as in the real wild. With many environmental stress/disturbance combinations, native species will individually survive by chance at some points and places, in combination with some (weakened) exotic species, then reproduce and eventually find their ‘natural’ position in the gradients provided as self-sustaining populations. That may be the future of many lowland, open habitat herbs. Then invertebrates, birds and lizards will find these plants and establish their ‘natural’ interactions. Meta-populations of such plants may form on roofs, walls, pavements, rock gardens, lawns etc. These habitats can be seen as forming an archipelago in urban environments!

But we can’t afford to be complacent and simply let aggressive introduced species take over. Some may be valuable as an interim stage back to a stronger representation of indigenous nature in the landscape. There are many cases in NZ of exotic shrubs and trees (Ulex, Pseudotsuga, Salix) acting as nurseries for native regeneration, but more often than not the continentally honed, introduced species are more successful in exploiting the periodic disturbances in human landscapes. It is also a slippery slope to promote ES and function as the hand maiden of biodiversity. To maximise dollar value of ES in NZ you would replace all indigenous, predominantly endemic, species with the most productive (invariably exotic) species from across the planet. So, is green form and function the goal? Surely not, for biodiversity, regional points of difference and identity. My position would be to work hard to find niches for all biodiversity, but don’t be hung up on a losing battle for “purity!” There is lots of good urban conservation to be done in recombinant ecosystems.

Meurk, C.D. 2011. Recombinant Ecology of Urban areas — characterisation, context and creativity. Pp 198-220 in Douglas, I., Goode, D., Houck, M.C., Wang, R. (editors), The Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology. Routledge, London.

Meurk, C.D., Greenep, H. 2003. Practical conservation and restoration of herbaceous vegetation. Canterbury Botanical Society Journal 37: 99-108.

about the writer

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course on conserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and published a book, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

Mark Hostetler

Around the world, cities are a mixture of exotic and native species. These novel or “recombinant ecosystems” represent unique plant and animal communities that have been purposely or accidently created by humans. The question posed for this roundtable is whether “native purity” is a viable option for urban green infrastructure. I would suggest that returning urban habitats to a semblance of past, native assemblages of species is unrealistic in most cities.

Instead, we should think about restoring urban habitats in terms of “reconciliation ecology,” where the goal is not to return to pristine, indigenous habitats, but to implement strategies that simply increase the diversity of native species in urban areas. Below, I touch on why we should increase native diversity in cities and why we should be careful about the types of exotics used in cities.

Natural heritage and the extinction of experience

With more and more people living in cities, the chance to experience and appreciate indigenous flora and fauna is in yards, neighborhoods and city parks. With the same generalist (exotic) species dominating cities around the world, this homogenized environment is what urban residents experience and they lose touch with their unique natural heritage. This exposure to a more degraded habitat and isolation from native plants and animals reduces peoples’ connection to nature and willingness to invest time and money for biodiversity conservation. Implementing strategies that increase the diversity of native plants and animals would expose citizens to local species, creating a sense of place. This strong identity with native plant and animal species ultimately raises awareness and support for biodiversity conservation.

Native animal diversity, in general, is correlated to native vegetation diversity.

Exotic plants in urban landscapes can require a large amount of care, which increases natural resource consumption and impacts on the environment. For example, turfgrass and some ornamental plants (e.g., roses) installed on nutrient poor soils in Florida means a homeowner has to irrigate, use herbicides and pesticides, and fertilize extensively to keep the grass and plants healthy. Excess fertilizers (e.g., phosphate and nitrate that is not taken up by yard plants) end up in local wetlands and water bodies when nutrients run off the landscape after a storm event. With pesticides, these chemicals are not specific to the pest insect and kill many native pollinators such as bees, beetles, wasps and butterflies.

Furthermore, the maintenance of turfgrass and ornamentals can actually cause a net increase in CO2 and other greenhouse gases. This is due to the use of fertilizers, irrigation and mowing of a manicured landscape, which takes fossil fuels, thus releasing CO2 into the atmosphere. Greenhouse gas emissions from yard management practices are greater than the amount of carbon stored by lawns and manicured ornamentals.

Exotics and risk of decreasing native plant and animal diversity

Selecting and installing primarily exotic plant species would ultimately decrease native plant diversity because of the simple fact that native plants would be absent from urban areas. Also, native animal diversity, in general, is correlated to native vegetation diversity. For example, native urban bird diversity increases with native vegetation; more native plants serve as host plants for native butterfly larvae; and native bee diversity increases with the occurrence of native plants. However, some exotics can provide food and shelter for native species. For example, butterflies obtain nectar from pentas (e.g., exotic cultivars of Pentas lanceolata) in Florida and elsewhere around the world.

Another risk associated with using exotic plants is that one may introduce invasive species into the environment. While many exotics are not invasive, some introduced plants are not designated as invasive until it is too late, having already spread from urban to natural areas. When exotic plants are used, known invasive plants should be eliminated and, where information is lacking about the invasive status of a plant, perhaps the precautionary principle should be applied. This states that if the risk is serious enough, the absence of full scientific certainty should not be used to postpone actions to prevent environmental degradation.

In summary, I propose that a goal for urban green infrastructure is not native purity, but a sensible mix of native and exotic plants. In cities, this means increasing the use and conservation of native plant and animal species; using exotics that are low maintenance and provide an ecosystem service, such as sequestering and storing carbon; using exotics that provide shelter and food for native animals; and not planting any exotics that have the potential of becoming invasive.

about the writer

Erle Ellis

Erle Ellis is Professor of Geography & Environmental Systems at UMBC and Visiting Professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Erle Ellis

Natives on the move: embracing change and evolution in biodiversity melting pots

The call to sustain native species in urban landscapes began decades ago in the U.S. Native plantings are now widespread. Partly in response to this trend, native wildlife—from songbirds to foxes, beavers, coyotes, wolves and bears—are returning to and thriving within regions they were driven from long ago. Native plantings are responsible to some degree, as native plant communities have been shown to sustain larger populations of native wildlife than nonnative plantings under some conditions. This is good news: a reversal of trends toward declining native biodiversity in landscapes increasingly inhospitable to wildlife.

Yet an exclusive focus on planting natives in urban landscapes might create more problems than it can solve. To begin with, the concept of a “native species” is, itself, a problem. Species are generally considered native based on a long history of inhabiting a specific area—but how long is long enough? In parts of Europe, species introduced before 1492 (“archaeophytes”) are distinguished from more recent arrivals (neophytes) and are therefore considered “more native.” European earthworms now predominate in soils across North America and no one realistically plans to eradicate these alien ecosystem engineers, despite their transformative effects on ecosystems. Outside the tropics, the native ranges of species have always been dynamic, migrating south ahead of glacial ice and north with the return of warming. Now, with climate changing faster than ever, species are moving north again. Attempting to keep species where they are “native” would involve limiting their northwards migrations. In the Anthropocene, there are negative consequences to labeling some species as natives and others not.

Novel communities often produce high levels of ecosystem services and provide valuable habitats for native wildlife.

What does “native” mean in an anthropogenic landscape full of built structures, tilled soils, excess nutrients and heat, pollutants, and other human-altered conditions? Urban ecosystems are novel ecosystems permanently transformed in biota and environmental conditions from those that existed before. It should be no surprise that novel ecosystems are full of species from other places, introduced both intentionally and unintentionally. Novel communities are the biodiversity mixing pots of the Anthropocene, bringing natives together with introduced species and immigrants from all over the world. Novel communities often produce high levels of ecosystem services and provide valuable habitats for native wildlife.

That seemingly inhospitable environments, such as brownfields and vacant lots, can support diverse and thriving novel communities rife with ecosystem services is truly remarkable, and these would generally not be possible if only native species were present. Some of the most common species in urban landscapes, such as the Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) and the Rock Pigeon (Columba livia) are found across the cities of the world. These are the true natives of the urban landscape.

To sustain the diversity of life on Earth over the course of the Anthropocene, extinction of species must be avoided while evolutionary processes that produce biodiversity are sustained. Quite often, native plantings in parks and yards are domesticates produced by large scale nurseries and seed corporations, and many are reproduced by cloning. These “natives” might as well be crops, and when they breed with remnant populations of wild natives, their narrow genetic base can reduce diversity in nearby populations of natives that are regenerating without human direction. By planting native cultivars, we may be helping to end the evolution by natural selection of our most favored native species.

As Earth moves deeper into the Anthropocene, species are on the move and coming together in ever more novel communities, ecosystems and landscapes—the biodiversity melting pots of the Anthropocene. It is time to assist native species in moving and to embrace a dynamic vision of what it means to be native: to belong in a place, whether it is urban, agricultural, seminatural or wild.

Are cities really the best places to conserve native species? The value of natives in cities is unclear, especially when these are domesticates. Biodiversity conservation is a global challenge and urban areas cover just a small percentage of Earth’s land. Yet the infrastructure of cities crosses continents; by redesigning transport networks, dams and hydrologic modifications, it may be possible to assist the migration of species responding to climate change. To conserve Earth’s remaining ecological heritage, it is time for our societies and our cultures of nature to embrace the dynamics of species on the move and the biodiversity melting pots of the Anthropocene—immigrants together with natives. We must work to sustain the wellsprings of evolution and biodiversity in the face of the unprecedented challenges of the Anthropocene.

about the writer

Matt Palmer

Matt Palmer is a senior lecturer in the department of Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology at Columbia University. His research interests are primarily in plant community ecology, with emphases on conservation, restoration and ecosystem function.

Matt Palmer

“Native purity” in urban ecosystems can be a useful aspiration—but it is a nearly impossible goal. It is far more reasonable to manage our dynamic urban biosphere based on the advantages and limitations of individual species, whether native or introduced.

There are certain urban places worth intensive management to maintain their historic biota.

There are merits to both positions. There are certain urban places worth intensive management to maintain their historic biota. But there are also many urban places so altered from their original conditions that few natives can persist without perpetual care and where introduced species provide services with less intervention. Then there is a wide spectrum in between—sites where a mix of native and introduced species provide services with limited management.

While it’s easy to advocate for the middle ground, there are challenges to making the “big tent” approach work:

Gardening vs. restoration

In principle, we could have any mix of species in any place. This is essentially gardening, and it can be very expensive. But many urban natural areas are only lightly managed, both by design—to “let nature take its course”—and because of the limited time, money and staff available to land managers.

Most projects to manage introduced species have a period of intense activity—cutting, spraying, trapping, replanting, etc.—with expectations for limited management after the target species are “controlled.” However, many projects fail—eradication is rare and populations of introduced species recover. Success requires an extended commitment to management. This presents challenges related to the expense and difficulty of long-term planning in politics, but also because managing in perpetuity will affect people’s experience of urban nature. Our natural areas will inevitably be less wild and more designed.

Measuring impacts

While almost anyone would agree we should prioritize managing the “worst” introduced species and worry less about innocuous ones, knowing which actions to take is hard. Some introduced species cause significant damage, but are so abundant or resilient that they are essentially unmanageable. Others may displace native species but provide a similar set of services, so they may not cause as much damage as assumed. Conversely, some apparently innocuous species may be present at low abundance for decades before their numbers and impacts increase rapidly. One of the only ways to stop an introduction is to intervene early. This creates a conundrum: act early and you may spend resources managing a non-problem; wait to act to see if a species causes problems and you lose the chance to control it. It may seem prudent to err on the side of caution, but that level of caution may be too expensive.

A fundamental challenge here is that damage from introduced species is hard to measure and especially hard to predict. Rigorous, data-driven evaluation of management options is quite rare. A lot of money is spent to manage species on hunches, and with limited monitoring to evaluate success.

The conservation imperative

The debate about intervention should consider the value of the species or places threatened by introduced species. If a native species is endangered, doing nothing may doom it to extinction—an irreversible loss. If the last remnant of native forest or endemic bird population is lost from an urban landscape, the opportunity for humans to connect to indigenous nature is lost. These lost connections make our day-to-day lives poorer, but also may affect the way we engage with nature broadly—with consequences for the whole planet.

about the writer

Leonie Fischer

Leonie works as urban ecologist at Technische Universität Berlin, where she focuses on vegetation dynamics, conservation and restoration in urban landscapes.

Leonie Fischer

Urban restoration: induced coexistence of natives and nonnatives in novel ecosystems

During transformational processes, many green spaces evolve in urban areas such as derelict industrial sites, unused train tracks or forgotten garden lots. The vegetation communities of such wasteland sites can bear few botanical treasures, but can also be characterized by the most common ruderal species. In either case, the participating species can be native and nonnative species alike.

Urban wastelands have a great potential for conserving and fostering biodiversity.

Given the homogenization of plant communities at the international level, I argue that urban wastelands have a great potential for conserving and fostering biodiversity. They can be used as refuges for rare and regional species, and (if succession is not the focus of conservation) can be optimized for habitat conservation. Techniques of ecological restoration adapted to an urban context can be used to establish substitute habitats that are lost outside cities. In such cases, the aim is to establish particular plant species and to ensure that they build viable populations in the long run. That means that target species need to be able to compete with their ruderal neighbors. In the end, they may jointly form novel types of species assemblages.

In my opinion, such restored plant communities do not need to display the historical stages of their reference ecosystems, but rather can be adapted to the ever-changing urban context. In addition to native target species central to conservation efforts, these communities may include those species that are best adapted to the site, independent of their origin. Only when this is true will restored sites function in the long run, without an exaggerated dose of maintenance and care.

Nevertheless, in the act of urban restoration, we can give a “signal” for native target species to establish on new sites, as these may not have gotten there due to spatial barriers or missing propagule pools in the surrounding.

Given that most city dwellers experience nature in their close surroundings by looking outside the window on their way to work, for example, I argue that their needs and preferences are of equal importance to what nature conservationists focus on. We should find out if people highly value certain natives or certain species assemblages that are dominated by natives (e.g., when defining target species for a restoration project). If urban restoration succeeds in identifying flagship species that are of native origin, the goals of both sides can be incorporated.

In the end, I speak up for (a) identifying and using the potential of urban contexts to foster native species, such as on urban wastelands, and thus contribute to a diverse, heterogenous urban flora, (b) welcoming urban plant communities that are largely a mix of species of different origins that rely on the environmental settings of a site, and (c) including aesthetic preferences of residents when choosing of a set of species, independent of the origin of those species.

about the writer

Bill Toomey

Bill Toomey is currently the Director of Forest Health working as part of the Nature Conservancy’s North American Forest Priority and Urban Conservation Strategies Initiatives.

Bill Toomey

Because many of them have been developed and built up over a period of hundreds of years, we now have a mix of native and nonnative species throughout our urban areas and cities. The species we now have in our cities are the result of choices made by millions of people, mostly independent of each other and based on person choices and preferences. Some urban nature is well planned and managed, such as in our city parks, gardens and roadsides, while other spaces are colonized by opportunistic and nonnative species. As land is converted into highly urbanized spaces, native habitats have been destroyed, altered and fragmented, and species that are not native to those areas have become established by accident or on purpose. Whether we like it or not, there are nonnative species living in our cities; they are taking advantage of the opportunity that disturbed areas and abandoned lands provide and which they are ecologically adapted to occupy. I am always amazed at the ability of some species to occupy marginal habitats and environments, such as cracks in paved areas, poor soils with high salinity or spaces with little access to water and nutrients. While there is benefit in establishing and maintaining areas that have exclusively native species, it may be unrealistic to think we have the time, money and resources to manage our existing urban areas and nature in cities with a purist, native-only perspective.

When planting, people should give preference to species that will do well in those local conditions, whether native or nonnative.

about the writer

Madhusudan Katti

Madhusudan is the Director of Science, Technology, and Society, and Associate Professor of Public Science in the Department of Integrative Humanities and Social Sciences at North Carolina State University.

Madhusudan Katti

The paradox of native purity in a fundamentally nonnative ecosystem

Cities in California are at a crossroads in terms of their long-term sustainability and resilience. While a couple of recent storms have brought some relief after a long, hot, dry, and fiery summer, and El Niño promises more precipitation this winter, these won’t be enough to address the long-term drought. California’s drought, of course, is a result not just of long-term climatic variability—dry spells are more the norm than the exception in the arid Southwest after all—but also of how people have sucked up and redistributed the state’s water.

Last May, the Governor declared an emergency, ordering mandatory cutbacks in water usage throughout the state. Water departments and utility districts scrambled to develop new policies and rules to enforce the restrictions. Many of California’s urban majority felt unfairly targeted because the thirstiest sector in the state is agriculture. Nevertheless, many of the cities managed to meet the conservation targets, cutting water use by a third in just a few months.

What are the consequences of such a reduction in water use? And how does this tie in to the question of native vs. nonnative species?

We don’t actually know how to cultivate and nurture many of the native species in urban gardens!

There is opportunity in this crisis for transforming these cities into more biophilic and resilient places in harmony with the regional climate and water availability. Indeed many residents are ripping out lawns and looking for alternative vegetation. Wouldn’t it be great if we could also get rid of all the “alien” species, and fill the cityscape with natives only greenery?

One problem with this vision of restoring “native purity” to this anthropogenic landscape: we don’t actually know how to cultivate and nurture many of the native species in urban gardens! In the Central California region, for example, there are but two local nurseries that supply native plants. There hasn’t been enough of the trial-and-error work that goes into domesticating native plants to turn them into marketable nursery products for the urban garden. Many of them also defy people’s expectation of “greenery,” and end up suffering from too much watering.

So there is a gap between the desire for native vegetation and our ability to actually grow native plants in cities in ways that meet the sociocultural, recreational, and aesthetic needs of people who live in urban landscapes. That doesn’t mean there aren’t other plants, from other regions, that can help us grow water-wise gardens. It would be foolish to turn away all such plants simply because they didn’t evolve in this part of the world. Worry about species likely to escape from gardens into the surrounding countryside, displacing native plants there, of course. But why let that worry get in the way of the benefits many other plants bring into our urban landscapes? We can keep working on domesticating more native species, even as we soften the urban landscape with a mix of whatever works to bring us the ecosystem services without sucking up too much water or disrupting native ecosystems. Nonnative species are not only here to stay, but can help us green the manufactured landscape of nonnative urban ecosystems.

about the writer

Ingo Kowarik

Ingo Kowarik is an expert on urban biodiversity, biological invasions and urban conservation approaches.

Ingo Kowarik

The alien-native debate is always good for hot controversy, but usually risks simplification. This particularly holds for cities. Here, “native purity” is as inadequate as is an “aliens welcome everywhere” approach. I thus think that it’s time to reconcile controversial positions and to come out with differentiated approaches! Why?

Good alien, bad alien? The right answer often depends on the context.

- Urban diversity requires diversity in approaches. Urban nature is often highly heterogeneous. Not everything is novel. Many cities comprise remnant ecosystems that stem from natural landscapes or traditional rural landscapes. Other green spaces have been created by humans, such as parks, or emerge as novel ecosystems in highly modified urban-industrial sites. Ecological analyses have revealed that different urban ecosystems have clearly different habitat functions for native and nonnative species, and for species of conservation concern in particular. Adopting only one general strategy for all urban habitats is thus unreasonable, regardless of claiming “native purity” or “aliens welcome everywhere.”

- Good alien, bad alien? The right answer often depends on the context. Take the highly invasive North American tree, Robinia pseudoacacia, as an example. It is known to threaten rare grassland species in Europe. Yet Robinia is also a highly valuable urban street tree, well adapted to climate change. From plantings, Robinia is spreading in Berlin and colonizes urban wastelands. Counterintuitively, our recent studies revealed no important effects on native plant or animal species when we compared Robinia to a native pioneer tree. At other sites, however, Robinia transforms (semi-)natural grassland with endangered species. In consequence, Berlin’s biodiversity strategy combines two aims in regard to nonnative species: if negative impacts on species or habitats of conservation concern are evident in a local context, nonnatives are managed. If not, they are accepted as part of ever-changing urban ecosystems. Such differentiation allows urban ecosystems to evolve and saves resources. Managing alien species always and everywhere would be highly costly and, as experience from many management projects shows, highly ineffective.

- Novel ecosystems, novel liaison between native and exotic species. Exotic species are often prominent in novel urban ecosystems and they underpin a range of ecosystem services. It’s thus reasonable to integrate nonnative species into the urban green infrastructure. Examples are: planting introduced trees where native trees don’t work or enhancing wild vegetation, usually a mixture of natives and nonnatives, in urban green spaces. “Novel wilderness” dominated by nonnative species has been successfully integrated in a range of parks in Berlin. Yet novel urban ecosystems can also contribute to the conservation of native species that use novel habitats as analogues to natural habitats. Since plants are usually dispersal limited—that is, they do not colonize each site where they might survive—it is also reasonable to enhance native species in some novel urban ecosystems. Leonie Fischer successfully tested adding native grassland species to urban wastelands in Berlin. Novel urban ecosystems thus also offer novel opportunities for native species, which might work in combination with nonnatives.

To conclude: Both natives and nonnatives are inextricable components of urban ecosystems. They occur in changing mixtures, usually responding to changing urban environments. Both species groups underpin ecosystem services that we urgently need in cities. It’s true: nonnative species can be a threat to native biodiversity, but this is often strictly context dependent. Evidence from Berlin shows limited conflicts, but this could be different in other cities. It’s necessary to analyze the local situation before acting. Be ready to enhance urban biodiversity by balancing risks and opportunities of individual species in individual situations—both for natives and nonnatives. Differentiation instead of simplification is promising for enhancing urban biodiversity in a changing world.

about the writer

Pippin Anderson

Pippin Anderson, a lecturer at the University of Cape Town, is an African urban ecologist who enjoys the untidiness of cities where society and nature must thrive together. FULL BIO

Pippin Anderson

How do I feel about exotic plant species in cities? Bring them on! How do I feel about invasive exotics in cities? Zero tolerance, extirpate!

I think so much of the beauty of cities is in their diversity. Individual cities have phenomenal diversity in their people, cultures, religions, views, gardens, buildings and public spaces. Indeed, different cities even smell differently. It is this very diversity that makes cities the “fonts of ingenuity” they are celebrated for. I believe the same goes for exotic species in cities. Why not embrace this element of human choice and conviction? It brings considerable joy to be able to select plant species, and people should have the right to choose based on preference, use, aesthetics, aroma and even just keeping up with the people next door. Indigenous species have a role to play in contributing to critical species pools and linking smaller city conservation entities, for example, but I think allowing freedom of choice among urban dwellers in what they plant will still see some people choosing to plant indigenous flora.

Diversity, including exotic species, makes cities the ‘fonts of ingenuity’ they are celebrated for.

Having said that, I do think we need to take an extremely firm view against invasive exotic species in cities. Cities are typical entry points for invasive exotic species. As these species do considerable ecological harm to indigenous communities, with ecosystem service and livelihood repercussions, it would be irresponsible not to take a firm and vigilant approach to invasive species in cities. I think turning a blind eye to invasive exotics in cities, or taking a view that they somehow be tolerated due to the urban setting, is something akin to ignoring a primary cancer.

So it appears to be something of a yes/no answer from me on this question, but I do believe the two categories are clearly differentiated. There is, of course, the potential threat, in light of anticipated change, that some currently benign exotics will turn invasive. What better place to keep an eye on this possibility, though, than in our cities? Here we have expertise, resources and the opportunity for considerable civic engagement (for example, the highly effective iSpot site). I believe we should embrace exotic species, which afford the public ecological autonomy and considerable joy, but we should simultaneously use the opportunity to engage the public and ensure people are educated in what is indigenous, exotic, and invasive. I believe the City of Cape Town is making considerable inroads in this area and their website presents a number of projects to this end.

about the writer

Paula Villagra

Paula Villagra, PhD, is a Landscape Architect that researches the transactions between people and landscapes in environments affected by natural disturbances.

Paula Villagra

Urban spaces are newer ecosystem types and imply thinking about and planning for them as hybrid systems, which are neither natural nor anthropic. If the aim is to ensure the functioning of the natural system and, simultaneously, to provide goods and services to humans, then contemporary urban spaces should be thought as novel “hybrid” systems. As such, instead of insisting on the “good natives, bad aliens” narrative, what matters is finding the proper coexistence between them to provide ecosystem services, such as recreation and mitigation, as well as to maintain ecosystem functions, such as interactions between processes and structures.

If the purity of the environment is relevant in urban areas, then that is what must be protected, and the planning and design of the urban environment will focus on creating buffer areas and strategies to conserve that. Conversely, if natural spaces require some kind of “help” for the community to value and take care of them, such as through the introduction of alien species to give scenic diversity (e.g. diversity of color), or man-made elements to make the place more familiar and accessible (e.g. by introducing trails), then the focus will be to study which elements, either natural, exotic and/or man-made, are possible and required to ensure a good perception of the environment and biodiversity conservation.

Green forms and functions, both native and introduced, should be welcome in contemporary ‘hybrid’ urban areas.

The planning of urban wetlands in Chile, in particular, should fulfill this dual role. Given the characteristics of the country, which has more than 4,000 km of coastline along the Pacific Ocean, there are many coastal wetlands in urban areas that provide ecosystems services such as: serving as buffer zones in case of tsunami, providing water for agriculture, being part of sacred land of aboriginal people and providing pleasant places for recreation. At the same time, urban wetlands are important natural reserves worldwide, as they are feeding and nesting sites for migratory birds and also contain a high number of endemic plant species.

Regardless of these values of urban wetlands, the actions of urban dwellers who do not know their valuable functions and services is sometimes negative. In the winter season, these wetlands can be seen as ugly and marshy places, so the community perceived them as dangerous sites and used them as landfills. In summer, due to the type of vegetation they have, they are perceived as dry and lifeless places, and as sources of fire, increasing insecurity and the negative perceptions of them. However, through national and international initiatives, several of these wetlands have been defined as priority conservation sites, and as coastal reserves. These interventions have gone hand in hand with environmental education programs and the introduction of information panels and vantage points for the observation of birds, including trails linked to urban parks. These types of actions provide the opportunity for recreation while facilitating the community’s understanding of the functions of these systems and associated services to humans. Then, the perception of the community can change, because the virtues of wetlands, which are sometimes difficult to perceive for the average citizen, are revealed.

In this sense, green forms and functions, both native and introduced, are welcome in contemporary “hybrid” urban areas. Planners, landscape architects, urban designers and ecologists, among other professionals involved in urban development and biodiversity conservation, should focus their efforts on identifying those parts, structures, processes and functions of systems, both natural and man-made, which should be kept or changed. And they should work together to prioritize strategies for providing services as well as for revealing functions that are intangible and invisible to the non-scientific community.

about the writer

Mark McDonnell

Mark has spent the past 25 years conducting ecological studies focused on understanding the structure and function of urban ecosystems, and the conservation of biodiversity in cities and towns.

Mark McDonnell

The preservation and conservation of native plants and animals in urban ecosystems is an admirable and ambitious aspiration considering cities have been built for people with little or no consideration of biological diversity for hundreds of years or more. Indeed, as Bill Cronon writes, defenders of biological diversity more commonly talk about wilderness areas rather than human-dominated ecosystems. Recently, comparative analyses of biological diversity in cities around the world demonstrate they are critical to maintaining global biodiversity. It is pretty clear that one of the greatest threats to native or indigenous plants and animals is the invasion of nonnative or exotic species. There is a large and growing body of research that demonstrates that the abundance and spread of these exotic invasive species is due to the direct and indirect action of humans.

Exotic species pose both a threat and a benefit for rapidly changing urban ecosystems.

Exotic species pose both a threat and a benefit for rapidly changing urban ecosystems. The ICUN recently published a report citing the significant threat of invasive alien species to Europe’s biodiversity. Conversely, Matt Palmer recently published a TNOC blog that discusses the many advantages of having exotic species in urban ecosystems. In general, many exotic species provide important cultural and ecosystem services in rapidly changing urban environments that are inhospitable to native species.

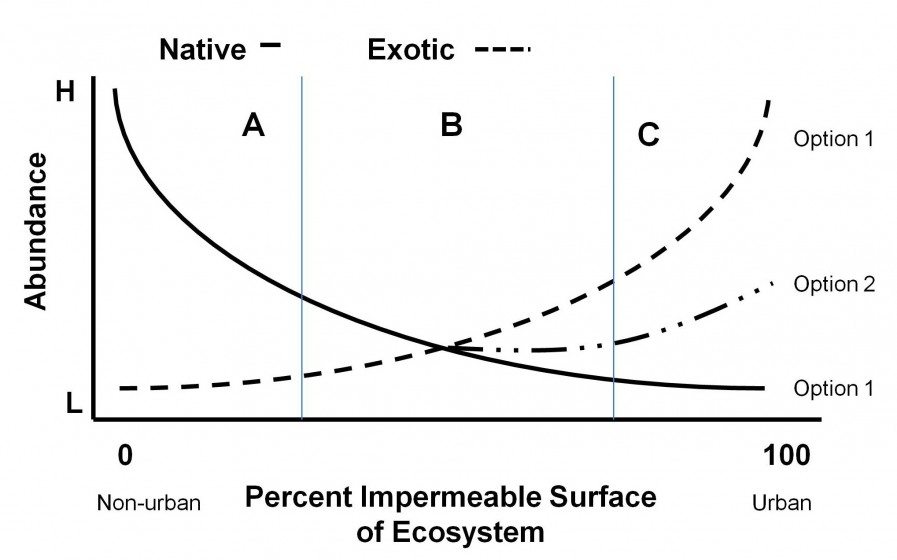

Because there are clear benefits to creating urban ecosystems that support both native and exotic species, I feel we need to move beyond this moral dualism where we view native species as ‘good’ and exotic species as ‘bad.’ Instead, we should adopt a concept of a ‘continuum of nativism’ (see the figure below) in which we assess the value of native and exotic species, as well as our conservation and restoration activities, as a function of the level of urban development. In the figure I use the percent of the urban ecosystem covered by impermeable surface as the measure of urban. As the percentage of impermeable surface increases in an ecosystem, there is a loss of native species and an increase in exotic species (C, Option 1). Option 2 represents the potential abundance of native species if planning, design, management and restoration practices are altered to support their survival. In Section A of the continuum, there may be little interest in maintaining native species because they are abundant in the ecosystems. In addition, exotic species would have little value in ecosystems that fall within this section of the Continuum. In Section B and C of the Continuum, we would expect more interest and support for preserving, conserving and restoring native species as they disappear (e.g., European cities). Cities that fall within Section B of the Continuum will still find it cost effective to maintain and restore native species. On the other hand, cities that fall within Section C of the Continuum may find it too difficult or expensive to preserve, conserve or restore native species. In this section of the Continuum, exotic species would be viewed as more valuable because they provide a variety of ecosystem services.

Leave a Reply