Pope Francis, City Planner

Pope Francis, City Planner

After reading Pope Francis’ Laudato Si, On Care For Our Common Home, I was moved to select references I felt relevant to efforts in Portland to integrate nature into the city and weave nature into the fabric of our urban and urbanizing neighborhoods. I sent a copy to David Maddox, who asked if I would consider adapting those excerpts into a blog for The Nature of Cities. What follows is my effort to do so. The entire text of “On Care for our Common Home” can be found here, in eight languages. It makes for good reading for anyone interested in the nature of cities.

“There is a need to protect those common areas, visual landmarks and urban landscapes which increase our sense of belonging, of rootedness, of ‘feeling at home’ within a city which includes us and brings us together.”—Pope Francis

Quite coincidentally to my reading of the Encyclical, it so happened that our mayor, Charlie Hales, had just received an invitation to attend a papal audience on Climate Change and human trafficking. Hales received his invitation on the strength of the city’s climate action plan, on its reputation for excellence in urban planning, and on President Obama’s 2014 naming of Portland as one of 16 national Climate Action Champions for Leadership on Climate Change. Sixty mayors from around the world were invited to Rome on the heels of a climate change gathering in Vancouver, British Columbia, to address modern slavery and climate change. The papal meeting was sponsored by the pontifical academies of sciences and social sciences.

The leaders were asked to share their city’s best practices, to sign a declaration recognizing that climate change and extreme poverty are influenced by human activity, and to pledge to make their cities “socially inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.”

So, what do Francis’ writings have to do with “the nature of cities,” ecological and social? A lot. For example, he laments the lack of greenspace under the heading “City Planning,” writing:

“Many cities are huge, inefficient structures, excessively wasteful of energy and water. Neighbourhoods, even those recently built, are congested, chaotic and lacking in sufficient green space. We were not meant to be inundated by cement, asphalt, glass and metal, and deprived of physical contact with nature.”

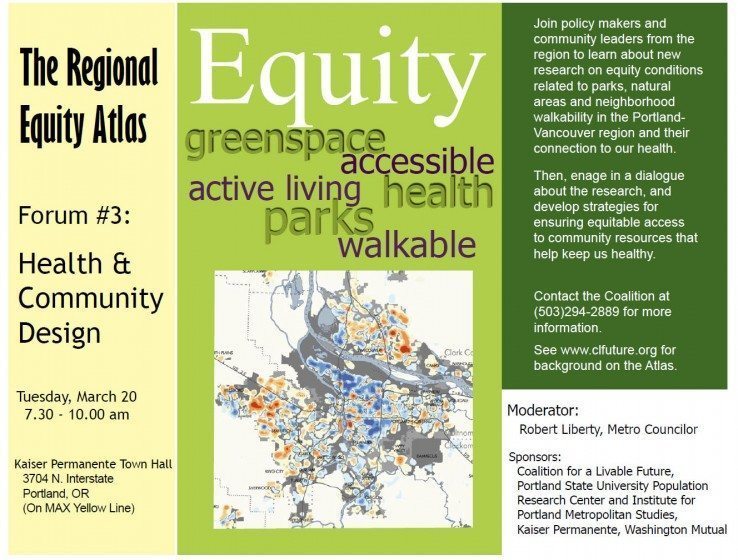

Within the context of city planning, Francis takes on the privatization of public space and inequitable access to parks and greenspaces, pointing out that wealthy, “ecological” gated communities have the lion’s share of urban parks and greenspaces, while “hidden,” poor neighborhoods—inhabited by what he describes as the “disposable members of society”—have little or no public space.

Francis makes the same arguments that many in our community have made for decades with regard to special landscapes and the Olmstedian precept that parks are catalysts for increased social cohesion.

He writes:

“There is also a need to protect those common areas, visual landmarks and urban landscapes which increase our sense of belonging, of rootedness, of ‘feeling at home’ within a city which includes us and brings us together…Interventions which affect the urban or rural landscape should take into account how various elements combine to form a whole which is perceived by its inhabitants as a coherent and meaningful framework for their lives. Others will then no longer be seen as strangers, but as part of a ‘we’ which all of us are working to create. For this same reason, in both urban and rural settings, it is helpful to set aside some places which can be preserved and protected from constant changes brought by human intervention.”

Housing and transit

He also delves into planning issues unrelated to “nature in the city,” but which are consequential to equity in urban development. He identifies lack of housing as “a grave problem in many parts of the world, both in rural areas and in large cities…”

Regarding transit, he writes:

“The quality of life in cities has much to do with systems of transport, which are often a source of much suffering for those who use them. Many cars…circulate in cities, causing traffic congestion, raising the level of pollution, and consuming enormous quantities of non-renewable energy. This makes it necessary to build more roads and parking areas which spoil the urban landscape. Many specialists agree on the need to give priority to public transportation. Yet some measures needed will not prove easily acceptable to society unless substantial improvements are made in the systems themselves, which in many cities force people to put up with undignified conditions due to crowding, inconvenience, infrequent service and lack of safety.”

The papal case for biodiversity and intrinsic value of nature

What struck me most about the Encyclical is the depth of scientifically-based discourse around biodiversity and the intrinsic value of nature. the fact that he received received a “chemical technician’s” degree and worked in a food-related laboratory cannot, alone, account for the depth of his arguments for the need to protect biodiversity, both for our own health and for the inherent value of the Earth’s biome.

In this regard, Francis, and with what is clearly remarkable stable of research assistants, writes of the importance of non-charismatic microfauna, recognizing the importance of species that are seldom, if ever, mentioned in urban planning contexts:

“It may well disturb us to learn of the extinction of mammals or birds, since they are more visible. But the good functioning of ecosystems also requires fungi, algae, worms, insects, reptiles and an innumerable variety of microorganisms. Some less numerous species, although generally unseen, nonetheless play a critical role in maintaining the equilibrium of a particular place.”

Regarding the intrinsic value of nature, the Encyclical says:

Regarding the intrinsic value of nature, the Encyclical says:

“It is not enough, however, to think of different species merely as potential ‘resources’ to be exploited, while overlooking the fact that they have value in themselves.

Each year sees the disappearance of thousands of plant and animal species which we will never know, which our children will never see, because they have been lost for ever. The great majority become extinct for reasons related to human activity. Because of us, thousands of species will no longer give glory to God by their very existence, nor convey their message to us. We have no such right.

We take these systems into account not only to determine how best to use them, but also because they have an intrinsic value independent of their usefulness. Each organism, as a creature of God, is good and admirable in itself; the same is true of the harmonious ensemble of organisms existing in a defined space and functioning as a system.”

Environmental impact analysis, biodiversity hot spots and biological corridors

The breadth of the encyclical’s reach with regard to fundamental ecological principles goes far beyond what most urban planners include in their planning regime, including environmental impact analysis:

“In assessing the environmental impact of any project, concern is usually shown for its effects on soil, water and air, yet few careful studies are made of its impact on biodiversity…”

Beyond simply addressing the importance of biodiversity, the encyclical specifies the important of biodiversity “hot spots”:

“In the protection of biodiversity, specialists insist on the need for particular attention to be shown to areas richer both in the number of species and in endemic, rare or less protected species. Certain places need greater protection because of their immense importance for the global ecosystem…”

Cost-benefit analysis

Pope Francis frequently excoriates “the market” as a contributor to human misery and environmental degradation. Therefore, it’s no surprise that he takes on market failures with regard to ecosystems and human health and well-being. He writes:

“Caring for ecosystems demands far-sightedness, since no one looking for quick and easy profit is truly interested in their preservation. But the cost of the damage caused by such selfish lack of concern is much greater than the economic benefits to be obtained…We can be silent witnesses to terrible injustices if we think that we can obtain significant benefits by making the rest of humanity, present and future, pay the extremely high costs of environmental deterioration.

It should always be kept in mind that ‘environmental protection cannot be assured solely on the basis of financial calculations of costs and benefits. The environment is one of those goods that cannot be adequately safeguarded or promoted by market forces.’ …Where profits alone count, there can be no thinking about the rhythms of nature, its phases of decay and regeneration, or the complexity of ecosystems which may be gravely upset by human intervention. Moreover, biodiversity is considered at most a deposit of economic resources available for exploitation, with no serious thought for the real value of things, their significance for persons and cultures, or the concerns and needs of the poor.”

Precautionary Principle

Francis also invokes the precautionary principle in writing:

“The Rio Declaration of 1992 states that ‘where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a pretext for postponing cost-effective measures which prevent environmental degradation…If objective information suggests that serious and irreversible damage may result, a project should be halted or modified, even in the absence of indisputable proof. Here the burden of proof is effectively reversed, since in such cases objective and conclusive demonstrations will have to be brought forward to demonstrate that the proposed activity will not cause serious harm to the environment or to those who inhabit it.”

Equity

Finally, as many contributors to The Nature of Cities have argued, and as is the case with planning efforts in Portland and many other U.S. cities, addressing climate change and city building in general must incorporate concern for equity, in all its dimensions and outcomes. This includes what I would term “interspecies equity” as it relates to the intrinsic value of nature (without regard to nature’s value to us) and to intergenerational equity as articulated in the Encyclical:

“The notion of the common good also extends to future generations…We can no longer speak of sustainable development apart from intergenerational solidarity. The environment is on loan to each generation, which must then hand it on to the next.”

Francis also addresses equity with regard to basic access to essential urban services such as affordable housing, clean air and water, and access to parks and nature.

* * *

I have referenced only a few excerpts from the Encyclical that I believe relate directly and indirectly to topics commonly discussed in the forum of The Nature of Cities. I encourage you to read the entire Encyclical, which abounds with additional insights into creating more ecologically sustainable, just and resilient cities that protect, restore and manage the natural systems that constitute our cities’ natural green infrastructure.

Mike Houck

Portland

Leave a Reply