The idea of the ‘neighborhood’ is reassuring, and it is our focus in this text, which explores how neighborhoods can help us to build and rebuild better cities for people. Good neighborhoods define cities and metropolitan regions at scales that are easier for us to relate to as humans, and as suggested in the days of yore by Gans (1962, 1967) and Morris (1969) perhaps more ‘natural’—that is, congruent with how humans have cohabited in smaller communities for thousands of years. In this series of three blog entries, we assert that good neighborhood planning is vital for more resilient and livable cities. The central argument is structured by two sets of questions and objectives:

- Why do neighborhoods matter for city-building? We consider positive and negative aspects of neighborhood-scale planning with particular attention to strengthening the complementarity and interdependence of civil society and the state.

- Why should we plan neighborhoods differently and more fully engage civil society in city-building? Creating better cities entails making neighborhoods a strategic focus for planning and action, as well as linking them to broader visions and strategies for progress toward ‘wholes that are greater than the sums of their parts.’ Civil-society organizations can play a pivotal role in developing ‘nested’ neighborhood strategies to strengthen cities and to drive innovation for positive social change.

The first entry (Why Do Neighborhoods Matter and Where Are We Going Wrong?) proposed that the time is right for rethinking neighborhood planning while warning about a paradox: as it conventionally has been done in the 20th century across the Anglo-American world, neighborhoods have been used to justify city-building strategies that are divisive both spatially—by setting clear geographic ‘limits’ that signal exclusion or exclusivity—and socially, by putting local interests ahead of broader interests of urban connectedness and complexity. Thus, while the motivations are noble, the practice has often been detrimental to the overall nature of cities for people.

Vital to the success of neighborhood planning is the avoidance of ‘superblock’ or ‘enclave’ approaches—what we describe as neighborhoods without borders.

This third and final entry tells a story from Montréal about a place-specific approach to good neighborhood planning: the Green, Active, Healthy Neighborhoods project. It explores what can be learned from the first five years of this place-specific work led by a civil-society organization (CSO). We present this case study to discuss how nested neighborhood planning can offer building blocks for better cities in a wide range of geographic, political and cultural contexts, if all three types of integration discussed in Part 2 are present. We weave in organizational and project aims, participant roles and a brief analysis of the project with respect to our four components of good neighborhood planning.

Context

The Green, Active, Healthy Neighborhoods project was led by the Montréal Urban Ecology Centre, a civil-society organization (CSO) that has existed for two decades, in collaboration with Quebec Coalition on Weight-Related Problems, a national partnership of advocacy groups and associations grappling with how to make it easier for Quebec’s population of eight million to eat well and to be more active.[1] The Neighborhoods project has received funding from several granting agencies with the mandate to develop and pilot a methodology for innovative community-based neighborhood planning. Detailed accounts of how the project developed and insights gained from the process can be found in a short article by Armand & Rochette (2011) and a longer piece by Blanchet-Cohen (2014).

The Centre is the lead player in this story. A small non-profit organization, it arose from a long, complex and intense struggle over neighborhood planning in the 1970s and 80s. As a major social movement contesting the destruction of a dense, socially-mixed urban neighborhood of Victorian housing located near Montréal’s downtown core, much of which had been bought up by land speculators seeking to replace the neighborhood fabric with tall apartment blocks, this battle marked the city’s history. The movement, documented by Hellman (1987), not only successfully ‘saved’ most of the local building stock, but went on to create Canada’s first and largest cooperative housing project. Several leaders of the local coalition sought to maintain the solidarity, energy and enthusiasm of the community-based social movement; in 1996, they established the Centre, which is housed in one of the neighborhood’s cooperative commercial buildings.

Since its inception the Centre has developed policies and practices to help create green, inclusive, just, democratic and healthy cities. Its approach is based on social ecology and the complex interdependence of social, economic, environmental and public health. Through its impressive accomplishments in participatory democracy, urban ecology and neighborhood planning, it has been recognized as a civil-society organization of significant importance and an active participant in a global urban movement for social change. It works primarily at the neighborhood and city scales, but also engages in special international projects, such as hosting the 2011 Ecocity World Summit.[2]

Project objectives

There is widespread agreement that a shift to modes of active and public transportation is key to reducing the negative health and environmental impacts of car-dominated urban form (Deehr & Shumann, 2009; Frank et al., 2004; Frumkin et al. 2004; Sallis et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2010; Tomalty & Haider, 2009). As dominant patterns of urban growth and development in North America are still car-centric, however, the Neighborhoods approach was developed to redefine existing neighborhoods so that they support walking, cycling and transit use.

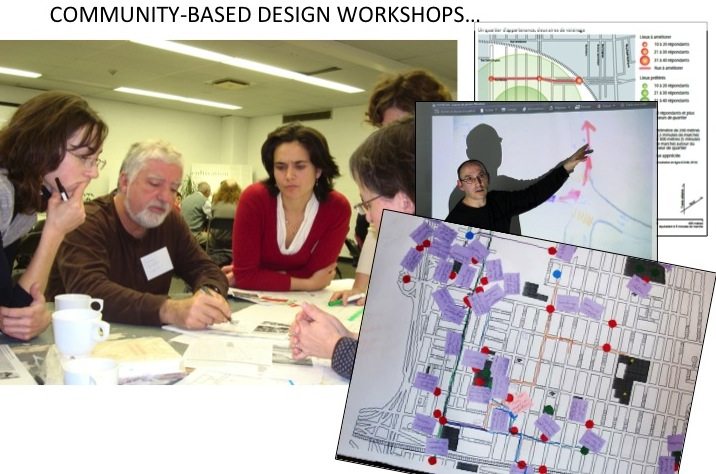

The Neighborhoods project also emerged in response to the need for concerted action in Canadian cities with growing awareness of the direct connections between the built environment of cities and public health (e.g., Frank et al., 2004; Purciel et al., 2009; Sui, 2003). It was launched in 2008 with support from key decision-makers in public health to address the problem of obesity among young people by developing participatory neighborhood plans to increase opportunities for safe active transportation (i.e., walking and cycling). It is articulated around six sets of core principles: 1) Public space and streets for people; 2) Safe active and public transport; 3) Strong people-nature connections; 4) Meaningful community engagement; 5) Sense of place and continual creativity; and 6) A long-term vision of urban livability. The Neighborhoods project aims to facilitate learning by the public, community stakeholders, elected officials and professionals in planning, engineering and design, specifically concerning how to design and create neighborhoods that make active transportation attractive and easy. It also strives to influence change in policies and professional norms and practices. The project involves research and dissemination of good practices, neighborhood-scale participatory planning, and public events and awareness-raising campaigns in four Montréal neighborhoods.

Participant roles

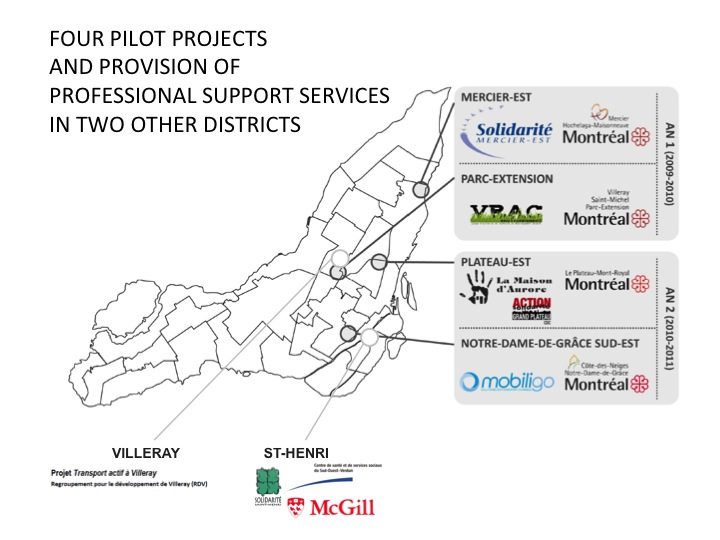

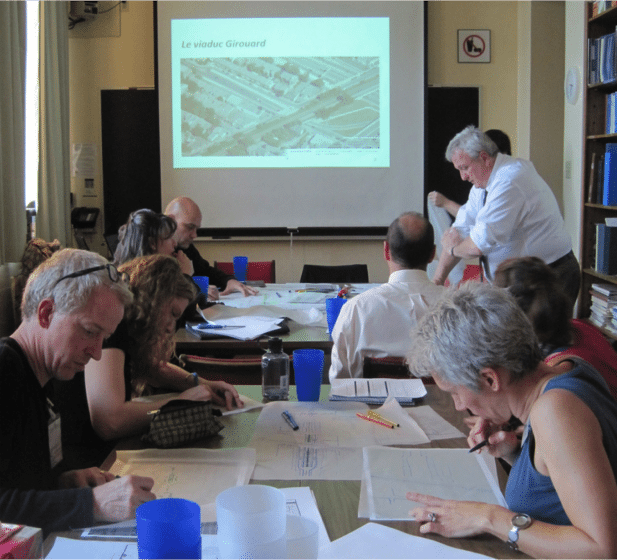

Green, Active, Healthy Neighborhood planning processes have now been carried out in four areas in Montreal. The Montréal Urban Ecology Centre led each of these by establishing local Neighborhoods committees comprising representatives of civil society and state institutions (including representatives of the local government) for each of the four pilot projects undertaken, bound together with a memorandum of understanding signed by the Centre, the local partner organization and the municipal authorities. Substantial public outreach ensured that local citizens were involved in various participatory strategies. The results have been quite positive: for the most part, local participants are very pleased with the processes and the plans that were produced. Not surprisingly, stakeholders have found it more difficult to implement the progressive plans and policies that resulted from community-based planning processes, and this work continues apace.

There is an interesting twist in the CSO-state relationship here, however. When the Neighborhoods project received funding in 2008, the City of Montréal adopted its new Transportation Plan; this included major policy directives based on the notion of quartiers verts (‘green neighborhoods’) developed in Paris. These are designated urban zones where steps are being taken to promote active transportation by increasing pedestrian and cyclist safety, including the introduction of aggressive traffic-calming measures to improve the quality of life for local residents. The Neighborhoods project enjoyed heightened recognition from the City and other stakeholders because it seemed to align well with policy. Soon after the adoption of the Transportation Plan, the City of Montreal launched its own parallel Green Neighborhood project and expressed a desire to collaborate with the Montréal Urban Ecology Centre in learning together as the parallel projects progress. Regular meetings took place to exchange information about innovative approaches. Interestingly, because the City did not fund or manage the Neighborhoods project, the Centre had the freedom to ‘push the envelope’ to recommend policies that more progressively favor active and public transportation along with more people-centered uses and configurations of public space. In fact, concerns arose that the city’s Transportation Plan approach implied a ‘superblock’ concept to traffic-calming by improving the quality of urban space within residential fabrics (on local streets) while shunting high-speed heavy traffic onto the main avenues that have defined the city’s armature for over a century. Without the unconditional support of the City, however, the Centre was limited in its capacity to implement the Neighborhoods plans once they were finished—or at least the aspects that relied on public infrastructure spending.

Successes and lessons learned

How does the Neighborhoods project stack up in terms of the four key components we suggest in these three blog entries? How is it vital for neighborhood-scale planning that also generates better outcomes for cities as larger, complex wholes? We start with social innovation, where the ‘expectations-motivation’ difference is evident between CSOs and state actors. Through many public initiatives and policy proposals introduced as elements of the Neighborhoods project, the Montréal Urban Ecology Centre has created synergies for positive change, raising the expectations of diverse publics in Montréal (and farther afield!) to create better neighborhoods and cities. Because the Centre is not confined to work within the constraints of existing municipal policies and regimes, it can ‘push the policy envelope’ and make recommendations in neighborhood plans that are consistent with bolder concepts. Swyngedouw & Moulaert (2010) warn that a project such as Neighborhoods must not be ‘captured’ by the state or its ‘innovative dynamics’ will weaken. The Centre’s capacity for social innovation is further strengthened by its glocal capacity and outlook. While staff members who work on Neighborhoods at the neighborhood level focus most of their energy on developing strategies for addressing local problems, the Centre as a whole maintains a broader global perspective and connection with international movements for creating resilient and livable cities.

Our second key component is the praxis of community development. The contested space between top-down and bottom-up approaches is tricky to navigate for any organization. It is constantly changing, and it can be very difficult to know how to make appropriate decisions, and on what to base those decisions. One early lesson learned in the Neighborhoods project is that advocates need to know when to push hard and when to relent on contentious matters. For example, in one of the study neighborhoods, the local Neighborhoods committee selected participants who were clearly not representative of local ethnic and cultural diversity. While the Montréal Urban Ecology Centre was uncomfortable with the situation and recommended changes to committee composition, the local committee resisted, and so the Centre backed down. A decision was taken as to which principle was more important to favor in this case: listening to and respecting what the local committee proposed as appropriate, or seeking to ensure equitable ethnic representation in a leadership group. Continually navigating contested space is not easy, but it helps to have a clear sense of which aspects of the planning process are most important and which are negotiable—in other words, for the CSO be what Friedmann (1989) and Sandercock (1998) usefully describe as a good ‘tightrope walker’ in progressive planning.

Vital to the success of neighborhood planning is the avoidance of ‘superblock’ or ‘enclave’ approaches—what we described in the second blog entry as neighborhoods without borders. This component represents an area of difference between the Centre, as a CSO, and the City on what to do with arterial roads. The Neighborhoods project includes arterial and commercial streets within neighborhood planning areas as well as traffic-calming strategies so that they are more amenable to walking and cycling. The City’s approach is more consistent with conventional planning, using major streets to define clear neighborhood boundaries onto which heavy flows of vehicular traffic are funneled. City policy does not clearly state the aim to reduce overall traffic volume, effectively guaranteeing increased traffic on arterials and the creation of neighborhood enclaves. As argued in section two, this runs counter to a holistic approach for nurturing resilient and livable cities. Contrasting municipal regimes are seen in Toronto, where local planning and infrastructure-building efforts have focused for almost 25 years on how to transform arterial roads into livable ‘avenues’ or boulevards (see Charney, 1991; Hess, 2009; Jacobs, 1991) and also in Minneapolis-St Paul (see Forsyth et al., 2010).[3]

Finally, the Neighborhoods project is explicitly aligned with a holistic vision of neighborhoods as integral to ecological democracies. A vision of cities comprising integral neighborhoods that continually weave urban ecological approaches with participatory democracy is consistent with the mission of the Montréal Urban Ecology Centre and its partners, and congruent in principle with the vision of the Neighborhoods project. The project focused primarily on improving conditions for active and public transportation and less on other considerations important for resilient and livable cities. This can be attributed to several factors: first, it aims specifically to address the problem of obesity among young people through modifying the built environment to favor active transportation; secondly, its main objective is to rethink streets as spaces for people—as what Derek Drummond (1991) called a city’s living room. Since city streets in North America have primarily been designed for the movement and storage of motor vehicles, the Neighborhoods project is primarily focused on challenging urban transportation norms. Finally, as mentioned, Montréal’s ‘green neighborhood’ concept was first articulated as urban policy in the city’s official 2008 Transportation Plan, and so it has become local convention to associate ‘green neighborhoods’ primarily with transportation, to the exclusion of other aspects of the Neighborhoods vision such as enhancing human-nature connections, increasing biodiversity and strengthening the sense of place for everyone who spends time there.

Reports by external analysts on the first phases of the Neighborhoods project confirmed that it was producing real results: the project reached a wide range of actors, and it was met with enthusiasm by many elected officials and professionals in private- and public-sector roles, who are exploring ways to enfold the project’s principles and values into their ways of doing things. Success was seen in outreach, popularization and public education, raising awareness among all sorts of citizens of the ways in which neighborhood-based initiatives can make a difference for resilient, livable cities. Familiar challenges arose on that front, however, with unevenness in terms of who participated. It is not easy to engage diverse publics in neighborhood planning even with a strategic approach that links interests, needs, capacity and possibilities for action. Local champions were found to be invaluable in making projects successes, and younger participants were found to be good ‘multiplier’ agents (spreading the enthusiasm and project content among different networks), but the appropriation of the project was found to be uneven from one pilot area to another. As planners have often discovered, not all neighborhoods are the same in terms of public interest, institutional capacity for discussing change and the potential for actually implementing proposed changes. Finally, one of the big questions that arose in the Neighborhoods project concerns how pilot projects can be successfully ‘scaled-up’ (or at least repeated as strategic methods) elsewhere in the city. This question is now being explored in the ongoing project work led by the Montréal Urban Ecology Centre, supported by Canada-wide partners.

On balance, the Green, Active, Healthy Neighborhoods initiative demonstrates strong evidence of carrying out neighborhood planning that contributes to resilient and livable cities. Infrastructure, policies and practices that prioritize walking and cycling represent substantial contributions toward city-building objectives such as compact urban form, cleaner air, decreased vehicular traffic, increased opportunities for everyday exercise, fewer transportation-related accidents and a host of other qualities centered on high-quality public space with ample vegetation and permeable surfaces to prevent urban heat islands (cf. Gehl, 2010; Larsen, 2015; North, 2013). Continuing challenges for the Neighborhoods project and its successor projects unsurprisingly have to do with effective implementation, continually balancing the CSO/state ‘tightrope,’ leveraging active transportation to more fully embrace a practical vision of resilient and livable cities, and getting beyond conventional approaches to defining neighborhoods so that major streets—the urban armature—take their rightful place as integral parts of resilient and livable cities for people.

Toward a new paradigm of integrated neighborhood planning

We have argued in three blog entries that neighborhood planning is an important strategy for creating resilient and livable cities. We propose neighborhood planning with a difference—combining social innovation with community development praxis to create well-connected neighborhoods within cities that are ecologically robust and defined by healthy practices of participatory deliberative democracy. Underlying our approach is the notion of integration (Luka & Lister, 2000): integrating neighborhood and city spatial scales; integrating capacities and domains of civil society and state actions; integrating local and global visions, thinking and action; and integrating theory and practice in collaborative participatory praxis. Participants in innovative neighborhood-focused city-building processes are continually redefining and negotiating these integral relationships in working toward shared visions of resilient and livable cities in practical ways that demonstrate clear evidence of progress to skeptics and supporters alike.

Making the leap from the cities we have to the cities we want requires social change, which includes citizens expecting more from their cities and contributing in new and creative ways. This is one important way that neighborhoods matter for building resilient and livable cities. People are more likely to connect with a city-building policy or project when it maps well onto their local neighborhood and when they play active roles in shaping it. This is vital to prevent one of the major risks and drawbacks we identified with conventional (old-fashioned) neighborhood planning: an overly prescriptive emphasis on physical attributes, often articulated in generic terms. The issue is arguably that city governments have often led neighborhood planning in North America. We have demonstrated through our Montréal case study how civil-society organizations can play pivotal roles in certain these processes through a range of engagement methods.

A second concern we identified in the first blog entry is that neighborhood-scaled ‘urban building blocks’ are inherently divisive by nature, for they can easily become enclaves. We cannot lose sight of the overall city context nor compromise on wider global issues. Great neighborhoods don’t necessarily make for great cities, as Biddulph (2001) has demonstrated. Cities that are resilient and livable are defined by great neighborhoods that are well connected and overlapping in their form and function, and in how people imagine them to exist. In these three blog entries, we have sought to show that neighborhood planning is worth doing if (and only if) it integrates four key components of ‘nested’ neighborhood planning that link neighborhood-scale planning to the work of ensuring better outcomes for the city as a whole: (1) social innovation, (2) community-development practice integrated with theory, often simply termed ‘praxis’, (3) neighborhoods without borders, and (4) a vision of ecological democracy. This multi-scalar approach links dimensions of thinking, planning, and building which are often disparate: integrating scales from the neighborhood to the city to the city-region, integrating action across domains of civil society and the state, and integrating value systems of urban ecology and participatory democracy.

Our closing comment has to do with civil-society organizations as critical agents in creating resilient and livable cities through neighborhood planning. They operate in a contested in-between space that Ledwith (2005) refers to as a space of ‘community-development praxis’—a space of continual negotiation between ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ forces—and this is why, as mentioned above, Friedmann (1989) and Sandercock (1998) speak of them as ‘tightrope walkers.’ As entities that challenge the dominance of the state and the market in liberal democracies, CSOs are the best example of what Susan Fainstein (1999, 2010) calls ‘counterinstitutions’ that are vital for effecting positive change for just cities. Through participatory collaborations in the contested praxis of community development, socially-innovative CSOs have the opportunity to negotiate relationships of power and engage methods for neighborhood planning that will contribute to collective action for social change to occur, making and continually transforming our metropolitan regions into resilient and livable cities for all.

Nik Luka and Jayne Engle

Montréal

Important links:

Montréal Urban Ecology Centre http://www.ecologieurbaine.net/en/

Links to Green, Active, and Healthy Neighbourhood plans http://www.ecologieurbaine.net/en/documentation-en/green-heighbourhood-plans

Quebec Coalition on Weight-Related Problems: http://www.cqpp.qc.ca/en/

Notes

1. The official title of the project, in French, is Quartiers verts, actifs et en santé; the Montréal Urban Ecology Centre is known as Centre d’écologie urbaine de Montréal and it ran the Neighborhoods project in collaboration with Coalition québécoise sur la problématique du poids. The project was funded primarily by Québec en forme and the Chagnon Foundation.

2. The Montréal Urban Ecology Centre hosted the 2011 Ecocity World Summit, in coordination with Ecocity Builders. Over 1500 participants from 72 countries and 280 cities around the world attended this event, the ninth in a series of international conferences, founded by Richard Register in 1990.

3. See also a recent study by Macdonald et al. (2010).

References

Armand, M.-H., & Rochette, A. (2011). Réaménager la ville, un quartier à la fois : L’initiative Quartiers verts, actifs et en santé. Urbanité (winter), 30-34.

Berman, M. (1986). Take it to the streets: conflict and community in public space. Dissent, 33(4), 476-485.

Biddulph, M. (2001). Villages don’t make a city. Journal of Urban Design, 5(1), 65-82.

Blanchet-Cohen, N. (2014). Igniting citizen participation in creating healthy built environments: the role of community organizations. Community Development Journal, 50(2), 264-279.

Charney, M. (1991). City structure as the generator of architectural form. Places, 7(2), 54-59.

Deehr, R. C., & Shumann, A. (2009). Active Seattle: achieving walkability in diverse neighborhoods. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(6), S403-S411.

Drummond, D. (1991). Streets can be a city’s living room. In B. Demchinsky (Ed.), Grassroots, greystones, and glass towers: Montréal urban issues and architecture (pp. 83-92). Montréal: Véhicule Press.

Fainstein, S. S. (1999). Can we make the cities we want? In R. A. Beauregard & S. Body-Gendrot (Eds.), The urban moment (pp. 249-272). Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

Fainstein, S. S. (2010). The just city. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press.

Forsyth, A., Nicholls, G., & Raye, B. (2010). Higher density and affordable housing: lessons from the Corridor Housing Initiative. Journal of Urban Design, 15(2), 269-284.

Frank, L. D., Andresen, M., & Schmid, T. (2004). Obesity relationships with community design, physical activity, and time spent in cars. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(2), 87-96.

Friedmann, J. (1989). Planning in the public domain: from knowledge to action. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Frumkin, H., Frank, L. D., & Jackson, R. (2004). Urban sprawl and public health : designing, planning, and building for healthy communities. Washington DC: Island Press.

Gans, H. (1962). The urban villagers. New York: Free Press.

Gans, H. (1967). The Levittowners: ways of life and politics in a new suburban community. New York: Random House.

Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for people. Washington DC: Island Press.

Hess, P. M. (2009). Avenues or arterials: the struggle to change street building practices in Toronto, Canada. Journal of Urban Design, 14(1), 1-28.

Jacobs, J. (1991). Putting Toronto’s best self forward. Places, 7(2), 50-53.

Larsen, L. (2015). Urban climate and adaptation strategies. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 13(9), 486-492.

Ledwith, M. (2005). Community development : a critical approach (Rev. 2nd ed.). Bristol: Policy Press / British Association of Social Workers.

Luka, N., & Lister, N.-M. (2000). Our place: Community ecodesign for the Great White North means re-integrating local culture and nature. Alternatives, 26(3), 25-30.

Macdonald, E., Sanders, R., & Anderson, A. (2010). Performance measures for complete, green streets: a proposal for urban arterials in California. Berkeley: University of California Transportation Center.

Morris, D. (1969). The human zoo. New York: McGraw-Hill.

North, A. (2013). Operative landscapes : building communities through public space. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Purciel, M., Neckerman, K. M., Lovasi, G. S., Quinn, J. W., Weiss, C., Bader, M. D. M., Ewing, R., & Rundle, A. (2009). Creating and validating GIS measures of urban design for health research. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(4), 457-466.

Sallis, J. F., Frank, L. D., Saelens, B. E., & Kraft, M. K. (2004). Active transportation and physical activity: opportunities for collaboration on transportation and public health research. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 38(4), 249-268.

Sandercock, L. (1998). Towards cosmopolis: Planning for multicultural cities. London: Wiley.

Smith, R., Reed, S., & Baker, S. (2010). Complete streets: from policy statements to programs and planning, opportunities abound for improving the accessibility of the transportation system for all users. Public Roads, 74(1), 12-17.

Sui, D. Z. (2003). Musings on the fat city: are obesity and urban forms linked? Urban Geography, 24(1), 75-84.

Swyngedouw, E., & Moulaert, F. (2010). Socially innovative projects, governance dynamics and urban change: between state and self-organisation. In F. Moulaert, F. Martinelli, E. Swyngedouw, & S. González (Eds.), Can neighbourhoods save the city? Community development and social innovation (pp. 219-234). London: Routledge.

Tomalty, R., & Haider, M. (2009). BC Sprawl Report: walkability and health. Vancouver: Smart Growth BC.

Ville de Montréal. (2008). Plan de transport. Montréal: Service des infrastructures, transport et environnement, Direction des transports, Division du développement des transports, Ville de Montréal.

about the writer

Jayne Engle

Jayne Engle is Curator of Cities for People and is a PhD candidate based in Montreal, Canada. She practices participatory community planning and development in the global north and south.

Leave a Reply