A review of the Large Parks in Large Cities conference, Stockholm, 2-4 September 2015.

The prognosis for urbanization is challenging—in the next 40 years, urban population will double. Under the growing pressure of modern urban development, large parks are valued by people more than ever. From the beginning of city development, large parks have played a very special role; originally, they were sacred groves, places for royal residence and hunting activity in addition to acting as public parks. The first conference entirely dedicated to different aspects of large parks was initiated by the World Wildlife Fund for Nature in Sweden and the Association for Ekoparken, in Stockholm, with the support of leading Swedish universities and NGOs.

The first conference entirely dedicated to different aspects of large parks was initiated by the World Wildlife Fund for Nature in Sweden and the Association for Ekoparken, in Stockholm, with the support of leading Swedish universities and NGOs.

Why were large parks chosen as a main emphasis of the conference? One of the keynote speakers, world famous American landscape ecologist, Richard Forman, clearly answered this question by emphasizing the importance of large parks (large patches of green) for preserving biodiversity, mitigating heat island effects and urban hydrology. Big parks are particularly treasured by most urban residents for recreation and are “a primary source of nature for human well-being in cities.” Large parks are the main “stepping” stones in urban green infrastructure and fulfill a variety of ecosystem services.

Large parks are an important basis for understanding cities’ natural and cultural histories, since some of them are oases left over from the original natural and semi-natural ecosystems. Big parks require particular attention and protection in developing countries, since they are the first green areas that are threatened to be reduced or even to completely disappear under the pressure of real estate prices. Thus, creating a network of people working with different aspects of large parks was also one of the main goals of the conference.

130 participants from 27 countries and six continents came to Stockholm. Presenters covered a wide range of visions for large parks in large cities, such as historical aspects, the role of such parks in the quality of urban life, creating sustainable green infrastructure and ecosystem services. Much attention was paid to the role of large parks in city planning and design and their relation to the European Landscape Convention.

The diversity and breadth of case studies of large parks around the world was striking. Some European cities, such as Stockholm and Moscow, are very lucky to have big national parks with wild nature within the city’s boundaries. Iranian, German, Colombian, Japanese and most U.S. cities are not so lucky—they tend to have “regular” public parks created in the 19th to early 20th centuries, in which tree groves and lawns are combined with water bodies and a wide range of recreational facilities. In some cases, in the absence of green resources in urban areas, such parks could include formal residential greens and even abandoned roads and railways.

It is also worth mentioning the role of Fedenatur, the European Association of Periurban Parks, where natural, fluvial and agricultural parks are located in metropolitan and peri-urban areas. Such parks can be found in Barcelona, Milan, Lyon and other cities in southern Europe.

Quite a few conference presenters discussed large parks in the broader context of urban green infrastructure. For example, Peter Clark pointed out that in 2009 in European cities, the proportion of green areas to total urban coverage ranged between 10 and 20 percent—a high proportion compared to 5 percent for Kuala Lumpur and 1.5 percent for Hong Kong, but less than Seoul’s 25 percent and Beijing’s 29 percent.

Clark expressed the importance of taking into consideration the multiplicity of economic, ecological, social and health impacts of urban green spaces. Today, not only big parks but wastelands, military exercising fields, old industrial sites, swamps, sport and recreation grounds, institutional gardens, private domestic gardens, allotment gardens, urban farms, boulevards, parkways, and roadside wedges should be re-valued. They can be “supporters” of as well as connectors to large urban parks.

In past centuries, when cities covered a rather small area, one could easily reach the nearest urban forest or pasture. With the growing congestion of industrial cities, fresh air, places for rest, berry picking and just walking in nature have started to become luxuries. In Stockholm, for example, the first public parks stemmed from formal royal parks, which were originally opened to the public from the middle of the 18th century (Kungsträdgården and Humlegården) under pressure from enlightenment actors. However, it took almost a hundred years for the city of Stockholm to plan and implement the first true public parks. In the late 19th century, two rather small parks, Strömparterren and Berzeli Park, were created. Djurgården, a former royal hunting ground, was situated just outside the built-up city and for many years compensated for the lack of public parks in central Stockholm.

Richard Murray, in his introductory presentation, demonstrated that in modern cities, land values vary a lot and even in very expensive places, such as New York, it is possible to find quite cheap pieces of land where green areas can be developed. If the costs and benefits of the ecosystem services that green areas provide were valued, developing green areas would be quite profitable.

The presentation by Mary Worrall and Sari Suomalainen on Birkenhead Park (U.K.) aroused particular interest among conference participants since it is the first publicly-funded park in the world to incorporate the concept of a park for people. This park was a catalyst and a model for the development of urban public parks in the U.S. and worldwide. The presenters’ analysis of social activities in this park uncovers the connection between the park’s history and today’s social use of the park.

Another European concept, the German “Volkspark” (People’s Park), flourished in the beginning of the 20th century. Such parks were based on natural landscapes and aimed to provide a wide range of recreational activities as well as to give work to unemployed people during the first years of WWI and the economic crises of the late 1920s.

A great example of a “Volkspark” is Amsterdamse Bos, which was developed in the 1920s and 30s with the help of 20,000 unemployed people. They turned empty agricultural land into a park full of diverse recreational facilities as well as amusing agricultural landscapes, such as a goat farm.

Parks and their role for biodiversity

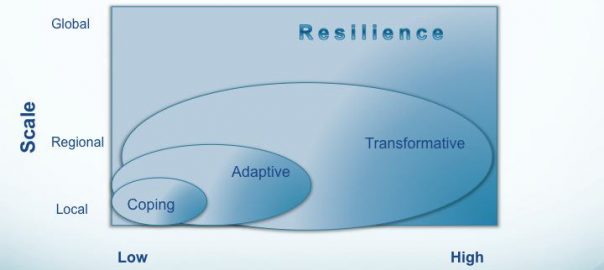

In the densifying urbanized world, large parks are becoming special refuges for biodiversity. Thomas Elmquist, the guru of ecosystem services research from the Stockholm Resilience Center, discussed the importance of continuous green areas. The United Nations’ Ecosystem Millennium Assessment clearly demonstrated the value of large patches of urban greenery for biodiversity in general. Elmquist cited Ban Ki-Moon, secretary general of the United Nations, who said: “The principal message is that urban areas must offer better stewardship of the ecosystems on which they rely.” Elmquist provided recent costs of restoring waste lands, patches of urban forests and similar habitats and concluded that ecosystem services in big cities pay their costs of upkeep several times over.

Negative tendencies in large parks

Positive experiences from different case studies from around the world were overshadowed by sad stories of how great parks have lately been neglected and even ruined.

One such example is the Patte d’Oie Forest Reserve in Brazzaville, the Republic of the Congo. Benoit Fondu pointed out that rapid urbanization has “eaten” quite a big piece of this forest and has also resulted in unfavorable changes in fauna and flora. Benoit suggested ways to save the remnants of this treasured urban forest, including by creating a fence, and, most importantly, involving local communities in protection of the Reserve.

In the Iranian part of Kurdistan, in the city of Sanandaj, a large park called Deedgah has another kind of problem. A newly constructed highway has divided the park. The consequences are visible: there is now limited access, more noise and more inconvenience for the park’s visitors.

Similar problems are being experienced by the National Park, Losinij Ostrov, in Moscow, Russia. The Moscow Ring Road now passes through the National Park for 7.5 kilometers, fragmenting habitat and creating barriers for the park’s fauna.

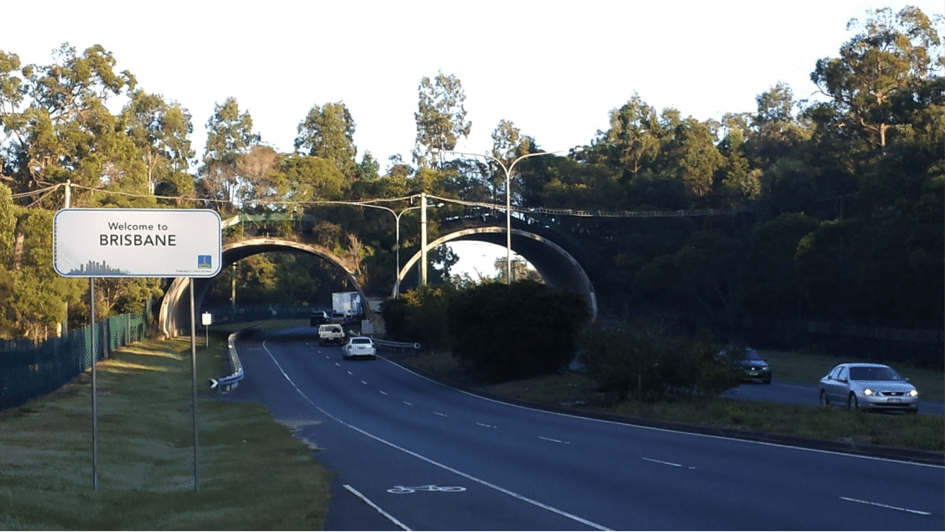

However, there are solutions to mitigate such problems, such as ecoducts. Wildlife passages that have proven successful in Australia, the U.S., the Netherlands, Sweden and in other countries.

Unfortunately, African countries seemed to be behind in solving the problems of large parks, especially in the fields of planning and design at the master plan level. Africa has the greatest national parks that are sources of pride for their respective nations, but urban parks urgently need care and awareness.

Nevertheless, there were some positive examples presented from Africa. A newly developed large park now exists in Ibadan, Nigeria. It was developed on a spot that previously had inaccessible, overgrown vegetation. Now, it is a popular spot for urban recreation. Another case study came from Beira, the second largest city of Mozambique, where a large, multifunctional city park, Parque Rio Chiveve, is being planned along the river. Here, unique White, Red and Black Mangrove ecosystems will be preserved and included in the park’s conceptual design.

Interestingly enough, a newly presented proposal—Medellin River Park in Colombia—has a similar aim: to restore the river’s ecosystem and bring it back to its citizens.

Human rights

Graham Fairclough brought up a very important point for discussion at this conference. He argued that urban parks should be seen not apart from the city, but as a part of the city. He asked: “Can a place be called a city if it has no parks?” His answer was: “Landscape is a culturally-enriched concept owned by everyone.” The Florence Charter and the European Landscape Convention are dealing with landscapes and proclaim that “landscape is an area as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors” and further that “landscape is at the heart of sense of place and identity.” Thus, parks must be seen as an important part of human rights. Citizens, therefore, have rights to participate in and influence the development of and changes to urban green areas.

Diversity of large parks

During the conference, some 20 parks had their own presentations, and many more parks, either already in existance or under design, were mentioned in thematic presentations. The diversity of approaches in research as well as in existing design and management practices was addressed through presentations on such subjects as transforming royal European parks to important green areas; restoring and adjusting parks to modern use, such as in Pavlovsky Park, the biggest landscape park in St. Petersburg; evaluating old English parks in Wales; discussing the activities of the Pittsburgh Park Conservancy; designing and managing Tehran’s Laleh Park; readjusting old Moscow parks to modern green infrastructure; mitigating the heat island effect of built-up areas, and much more.

There were quite a few examples of recently designed public parks: Emscher Landscape Park in Germany, a series of large parks in the Netherlands, a new nature park in Copenhagen, and designs for parks as part of green wedges in Swedish Gothenburg, Silesi Park in Poland, Ataturk Culture Park in Antalya, Turkey, and Flushing Meadow-Vorona Park in New York City.

The breadth of this park research opened our eyes to such new aspects as social study on crime in urban parks in Malaysia, community response to environmental changes resulting from Yatsu-higata Park in Tokyo, or fauna passing between urban parks in Brisbane, Australia. Likewise, presentation on park arthropods helped in understanding the significance of new research and the connection of arthropods to practical issues for protection and maintenance of large park ecosystems.

An impressive example was presented by Carmela Canzonieri, who shared a design proposal for a large park in Mexico City. The proposed park would be developed on an abandoned airfield. Ambitious designers are dreaming of reintroducing waters that have been buried for centuries and of creating a multifunctional public space.

Julia Czerniak, the leading large parks researcher from the United States, gave a special contribution. She talked about recently implemented parks such as Fresh Kills (south of Manhattan in New York on Staten Island), as well as examples from Singapore and Qian Hai Water City in China. Czerniak emphasized the importance of an ecological design approach and the use of knowledge and principles of urban ecology in designing and planning large parks.

The practical output of the Stockholm conference on big parks was the suggestion to include a section for large urban parks within the newly created organization “World Urban Parks.”

Maria Ignatieva, Richard Murray and Henrik Waldenström

Uppsala and Stockholm

about the writer

Richard Murray

Richard Murray, PhD in Economics from the University of Stockholm, is president of Ekoparken Association since 1993, initiated a local political “green” party in 1978, and is senior advisor to Global Utmaning (Global challenge).

about the writer

Henrik Waldenström

Henrik Waldenström is an officer at the World Wide Fund for Nature in Sweden and specializes in green areas in cities.

Leave a Reply