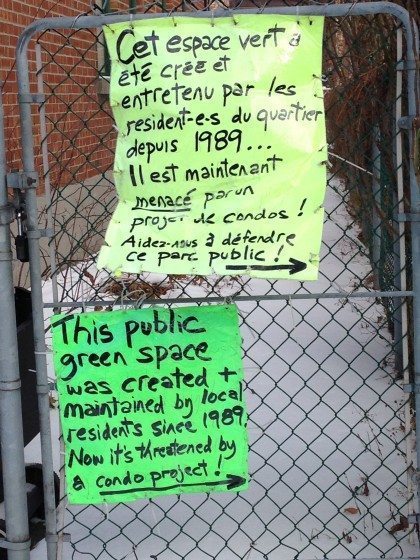

When Montréal’s Parc Oxygène was bulldozed in June 2014, a local newspaper article aptly spoke of a ‘neighborhood in mourning.’ The narration of its destruction by a neighbor is heart-wrenching (1). This small park in the midst of high rises was an urban oasis made and looked after by its neighbors for more than two decades (2). Parc Oxygène was created out of a laneway that was once used as a shortcut by motorists. This form of use represented a danger to local children until residents took it upon themselves to replace tarmac with vegetation—a somewhat radical, but essentially civically responsible, act.

The destruction of Parc Oxygène elicited feelings of shock, frustration, devastation and despair. This outpouring was a direct consequence of the emotion that had been invested in this small site. It reflected a deep engagement with place, nature and community on the part of many people. Local governments are increasingly encouraging citizens to take responsibility for looking after and enhancing urban spaces, and many citizens are keen to take on such roles. However, Parc Oxygène is an example of how a potentially win-win scenario can, instead, end in tears.

Parc Oxygène occupied a privately owned space, a situation which is not uncommon among places cared for by citizens—and not necessarily less secure than citizen-led initiatives at public sites. As long as the owner did not want to develop or sell the land, Parc Oxygène could continue to exist, to the apparent satisfaction of many. There were ongoing calls for local government to purchase the land to secure the park’s future, but this demand was never met. When the owner eventually confirmed an intention to build on the land, the community waged a political and legal battle to save it. While government representatives expressed their sadness at the impending loss of the park and their sympathies with the local community, they did not consider purchase of the land justifiable—suggesting instead that the eventual creation of a green space of a similar or larger size could compensate for its loss.

The legal appeal to save Parc Oxygène was focused on ‘right of way’ and a safeguard order (temporary injunction) was sought to prevent construction on the site while this question was properly considered. The court refused to issue the safeguard order, stating that the right of way was questionable and, even if established, was not relevant to emission of the construction permit because a passage would remain between the existing and new buildings. The judgment also conveyed disapproval of what the tribunal perceived as an effort to transform a right of way into a right to plant trees and make a park (Syndicat de la copropriété communauté Milton Parc v. 9251-3191 Québec inc., 2014).

While the effort to save Parc Oxygène by invoking right of way was not successful, there was, at least, a framework in place to defend the principle. But what about a customary ‘right of care’? What value is given to two decades of a collective labor of love? Or to the place in the hearts of many Montrealers that Parc Oxygène occupied? Not very much, it appears.

Valuing engagement

It was notable that local government representatives and engaged citizens employed a very different style of discourse when speaking about the loss of Parc Oxygène. A neighbor and friend of the park described how: “It took 20 years to build and about 20 minutes to destroy; our neighborhood is now mourning.” (Lalonde, 2014) Whereas a City Councilor justified the decision by saying: “At this point, the only way to keep it would have been for the borough to acquire it and that would have simply cost the borough too much. It would have cost about half-a-million dollars for a plot that is only seven meters wide.” (Ibid.)

For the individual engaged with Parc Oxygène, its value is expressed in terms of the time that volunteers have spent making the park. The result of its destruction is deeply emotional; it elicits ‘mourning.’ The Councilor, on the other hand, while acknowledging that “It is wonderful that a group of people invested so much energy in creating a garden and keeping it so pretty for so long,” focuses on the size of the plot and promises, in the same interview with a local journalist, “to compensate for the loss of greenery in the neighborhood” (Ibid.) He commits to ensuring that the neighborhood “has more green and public spaces, bigger than the size of this lot” (Ibid.)

For the Councilor, Parc Oxygène is interchangeable with other plots or lots that provide green space and public access. Its affective value is discounted. Similarly, the Councilor speaks of the worth of Parc Oxygène in terms of the monetary value of the land and concludes that its cost is too great: “You have to look into your heart and ask if you can really justify spending that much money on such a small plot of land when we have a limited budget. We have to make choices” (Ibid.)

Perhaps half a million dollars sounds like a lot, but not when you think about things like the cost of snow removal. The City of Montreal spends on average $155 million a year (“Ville de Montréal – Déneigement Montréal – Opérations de déneigement,” n.d.) in order to ensure that traffic can move about unimpeded and cars can be parked on the sides of streets (3). Or, one can think about the value of what has replaced Parc Oxygène: a few apartments. This has not made any significant contribution to local housing availability, as they are situated in what was already one of Canada’s most densely populated neighborhoods.

The City Councilor is a member of a party that occupies all of the seats in the borough and is very supportive of both greening and citizen action. The party was founded by environmental activists and continues to call upon citizens to engage in the protection of green space, such as in its current campaign to protect Mount Royal (http://www.monprojetmontreal.org/rutherford). However, when push came to shove, the Councilor appealed to citizens to be rational and accept that the cost of protecting Parc Oxygène was too high because it was small and presumed to be of little ecological significance. The engagement of citizens and their emotional attachment was implicitly understood as having less value than other things that might place demands on public funds.

Why is citizen engagement with urban green space so little valued?

Citizens are increasingly called upon to play a role in looking after urban spaces as local governments struggle to maintain public green space and to regenerate ‘derelict’ land. Citizens agree to take on these responsibilities because they care and because they enjoy the work involved. Therefore, it appears to be in everyone’s interest to invite this sort of engagement.

However, this approach does not sit comfortably with conventional ways of governing. It generally entails broadening the possibilities of what can happen in urban spaces and many engaged citizens will not content themselves with tidying up and watering trees. So by promoting the value of responsibility for collective space, the diversity of interventions that follow may challenge certain other values.

The unpredictability of outcomes may lead to surprises—and surprises can be good, because they lead to new thinking. But the non-standard character of citizen-managed spaces may appear to some people to be somewhat messy and chaotic. These spaces may not fit the stereotype of either ‘natural area’ or ‘well-managed park.’ This is one reason that such places and the work of the citizens may be undervalued.

Urban nature also tends to be generally undervalued. It may sometimes be invisible to the uninitiated, and in some cases the value (from a human perspective) is only created through the relationship, i.e. the collaboration between people and nature.

As Hinchliffe et al. (2005, p. 643) assert: “Cities are inhabited by all manner of things and made up of all manner of practices, many of which are unnoticed by urban politics and disregarded by science.” However, “engagements with a place on a day-to-day basis, or through less frequent but recurrent visits, can generate a sensibility about, or intimacy with, ecologies of place” (Hinchliffe & Whatmore, 2006, p. 131). At a threatened site in Birmingham, U.K., the researchers, along with volunteers and ecologists from a local conservation organization, attempted to engage fully with the place and the nonhumans who lived there. In this way, they were able to recognize the presence of a species that had gone unnoticed during an environmental impact assessment because its practices were different than those noted by scientists in other settings (Hinchliffe et al., 2005).

It is also difficult to appreciate the social, cultural and ecological assets of a place without living in it. Ecosystem services are more likely to be recognised by those who benefit from them. Spending time in a Manchester alleyway transformed by citizens reveals a range of supporting, regulating, provisioning and cultural ecosystem services.

And, of course, everything looks different when you make (or renovate) it yourself.

The process of engagement itself is undervalued by the unengaged. That long process through which we gradually connect with a place: storing memories, deciding to take responsibility, starting to take action to make the place better… it’s what most people do in their own homes, but for many it is difficult to imagine extending that feeling into a wider, shared realm.

And when the primary mechanism for decision-making is determining spending priorities, the value of citizen engagement and labor becomes invisible—it is effectively zero. In monetary terms, it is seen as ‘free’ and it does not appear in the budget or the list of assets. However, when governments call on citizens to engage, they are often, in effect, doing the calculation; they are hoping that citizens will take on tasks that would otherwise need to be paid for. Should they not, therefore, take some responsibility to ensure that there are returns on citizens’ engagement?

Perhaps it is time to account for the value of spaces of citizen engagement. As in-kind contributions are assigned monetary value in grant proposals, it might be interesting to try to do this for the value of certain sites—because one can assume that the effort that has been put into them is some reflection of their worth. This would make an interesting contrast with the more common contingent valuation methods that ask what people would pay (if they had to pay) to use or simply protect environmental qualities and ecosystem services. Within the former perspective, citizens become active participants collaborating with nature, rather than existing as consumers or distant protectors of nature (from other humans).

Designating and protecting places that matter to communities may be an appropriate way to assign value to spaces of engagement. Manchester City Council developed a Local Nature Reserve designation for places that were not necessarily biologically important, but were important to local communities. They have an explicit function “to provide opportunities for people to become involved in the management of their local environment as well as giving people special opportunities to study, learn or simply enjoy nature.”

The right to the city should include a right to engage with nature

It is worth noting that in the case of Parc Oxygène, citizens were understood to have a potential claim to a right of way. Rights of way are well protected in some countries, so why not a ‘right of care’ or a ‘right of attachment’?

As the poet Norman MacCaig (1969) asks in his poem A Man in Assynt:

Who owns this landscape?

Has owning anything to do with love?

For it and I have a love-affair…

Hinchliffe and Whatmore (2006, pp. 132–133) describe a moment when the people engaged with the threatened Birmingham site created a willow sculpture, explaining that “they want to be involved in doing something to express their anger that despite all their efforts it seems as though development will go ahead on this site with little or no attempt to secure ecological potential. They are local residents, activists from the Birmingham and Black Country Wildlife Trust, people who grew up near the site. They are all trespassing, as this is private land, even though they have used it for years as a place to watch wildlife, to walk in and through, to climb trees, to look upon from home and the nearby allotments.”

Should there not be a right to urban nature? As the city has evolved from a place where people went to market, and then to work, and, now, into the dwelling place of the majority of people on Earth, we may have different needs to fulfill and new rights worthy of recognition. It has been suggested that our relationships with other species are changing: An increasingly urban population has moved from a utilitarian perspective, to an ecocentric view that sees nature as best kept separate from people, to a new tendency to seek more interactive relationships, involving activities such as feeding birds instead of eating them. (Buijs, Elands, & Langers, 2009; Teel, Manfredo, & Stinchfield, 2007)

If our relationships with other species are evolving and we no longer need hunting grounds or places to graze livestock, and we are perhaps less excited about gazing passively at formal gardens, we may require different kinds of urban spaces. Perhaps we need new kinds of urban commons where we can interact with urban nature in a diversity of ways.

Parc Oxygène was the subject of a lengthy political struggle, which appeared to have garnered considerable support. Failure to save it was due in part to a lack of policy tools—and perhaps to a lack of language to talk about what urban places and urban nature mean to the citizens who engage with them. Its value was not recognized as being of the sort that can provide justification for budget allocations. There was no existing designation for a ‘site of community engagement’ and, as Hinchliffe and Whatmore’s work in Birmingham showed, ecological significance can be difficult to demonstrate using conventional measures. The engaged citizens are sometimes the only ones who can see it.

There was no protection of customary ‘right of care’ in the way that there was for ‘right of way.’ And there was no way to declare that, thanks to the dedication of citizens, a pedestrian right of way had also become a park, guaranteeing a right of access to urban nature in the manner that right of way in the U.K. often ensures right of access to the countryside.

A discussion remains to be had concerning what kinds of new commons are required to meet the needs of humans and other species in cities. But one thing is clear: if citizens are called upon to engage, then the depth of that engagement must be recognized and valued. Expectations of responsible citizenship demand responsibility toward citizens and to the places—and the nature—that they love.

Janice Astbury

London

End Notes:

(1) See article and short video at http://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/neighborhood-in-mourning-as-parc-oxygene-razed-for-condo-development.

(2) See https://www.facebook.com/parcoxygene for the recent history of Parc Oxygène and the efforts to save it.

(3) See http://www.wildaboutmanchester.info/www/index.php/local-nature-reserves but note that the list of Local Nature Reserves on this page is out of date and others have been added.

References:

Buijs, A. E., Elands, B. H. M., & Langers, F. (2009). No wilderness for immigrants: Cultural differences in images of nature and landscape preferences. Landscape and Urban Planning, 91(3), 113–123.

Carson, R. (2011). The Sense of Wonder. Open Road Media.

Hinchliffe, S., Kearnes, M. B., Degen, M., & Whatmore, S. (2005). Urban wild things: a cosmopolitical experiment. Environment and Planning D, 23(5), 643.

Hinchliffe, S., & Whatmore, S. (2006). Living cities: towards a politics of conviviality. Science as Culture, 15(2), 123–138.

Lalonde, M. (2014, July 27). “Neighbourhood in mourning” as Parc Oxygène razed for condo development. Montreal Gazette. Montreal. Retrieved from http://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/neighbourhood-in-mourning-as-parc-oxygene-razed-for-condo-development

MacCaig, N. (1969). A man in my position. Chatto & Windus.

Syndicat de la copropriété communauté Milton Parc v. 9251-3191 Québec inc., 2014 QCCS 3012. Retrieved from http://citoyens.soquij.qc.ca/php/decision.php?ID=A75BD8513CE46EF45219AFAA53D81017

Teel, T. L., Manfredo, M. J., & Stinchfield, H. M. (2007). The Need and Theoretical Basis for Exploring Wildlife Value Orientations Cross-Culturally. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 12(5), 297–305.

Ville de Montréal – Déneigement Montréal – Opérations de déneigement. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved July 16, 2015, from http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=8217,136273620&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL

Add a Comment

Join our conversation