about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

In May of 2014, TNOC published a roundtable on why we needed an urban Sustainable Development Goal to be one of the SDGs under consideration by the UN. At that time, an explicitly urban SDG was anything but certain, and a large coalition of urbanists was working hard to make urban issues explicitly part of the UN’s sustainability agenda. Well, an urban SDG was, in fact, adopted as one of 17 new sustainability goals that will propel work through 2030.

The final SDG Goal 11 is stated this way: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. There is a lot of meaning to be explored in these seven words. What does “inclusive” mean in an operational sense? “Safe” from what? Safety for whom? The word “sustainable” makes clear that cities are part of larger, globally interconnected chains of resources that transcend old fashioned rural-urban boundaries. But such an integrated view is at odds with the fact that urbanists and non-urbanists (for lack of a better phrase) typically work in separate spheres. The head spins.

There are ten targets for SDG#11 that start to unpack the SDG’s meaning and philosophy, and also imply actual measures of progress:

- By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums

- By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons

- By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries

- Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage

- By 2030, significantly reduce the number of deaths and the number of people affected and substantially decrease the direct economic losses relative to global gross domestic product caused by disasters, including water-related disasters, with a focus on protecting the poor and people in vulnerable situations

- By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management

- By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities

- Support positive economic, social and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning

- By 2020, substantially increase the number of cities and human settlements adopting and implementing integrated policies and plans towards inclusion, resource efficiency, mitigation and adaptation to climate change, resilience to disasters, and develop and implement, in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, holistic disaster risk management at all levels

- Support least developed countries, including through financial and technical assistance, in building sustainable and resilient buildings utilizing local materials

This is a great, even historic start. But it is only the beginning, and much, much work remains between now and the Habitat III Conference, and then through 2030, to accomplish the goal.

So, now what? Now that we have the goal, what is our path to success? What are the pitfalls? What could go wrong? These questions are the subject of this roundtable, including many of the contributors to the May 2014 panel, and adding new voices from around the world. We invite you to join the conversation also.

about the writer

Genie Birch

Professor Genie Birch is the Lawrence C. Nussdorf Chair of Urban Research and Education, former Chair of the Board of Trustees for the Municipal Art Society of New York, and co-chair, UN-HABITAT's World Urban Campaign.

Eugenie Birch

Monitoring SDG 11: geospatial technologies offer hope for solutions, but we have a lot of work to do…

Now that the SDGs are a reality, implementation is going to be the name of the game, and crafting the protocol for monitoring is the next step in that game. As with the MDGs, the United Nations will ask nations to report on the SDG targets—all 169 of them—and at present, is working to develop indicators to provide a set of simple, uniform measures. Sound easy? Well, it’s not. Remember: the SDGs are universally applicable and not all nations have deep data collection capacities. But this situation opens the door to employing new means of monitoring.

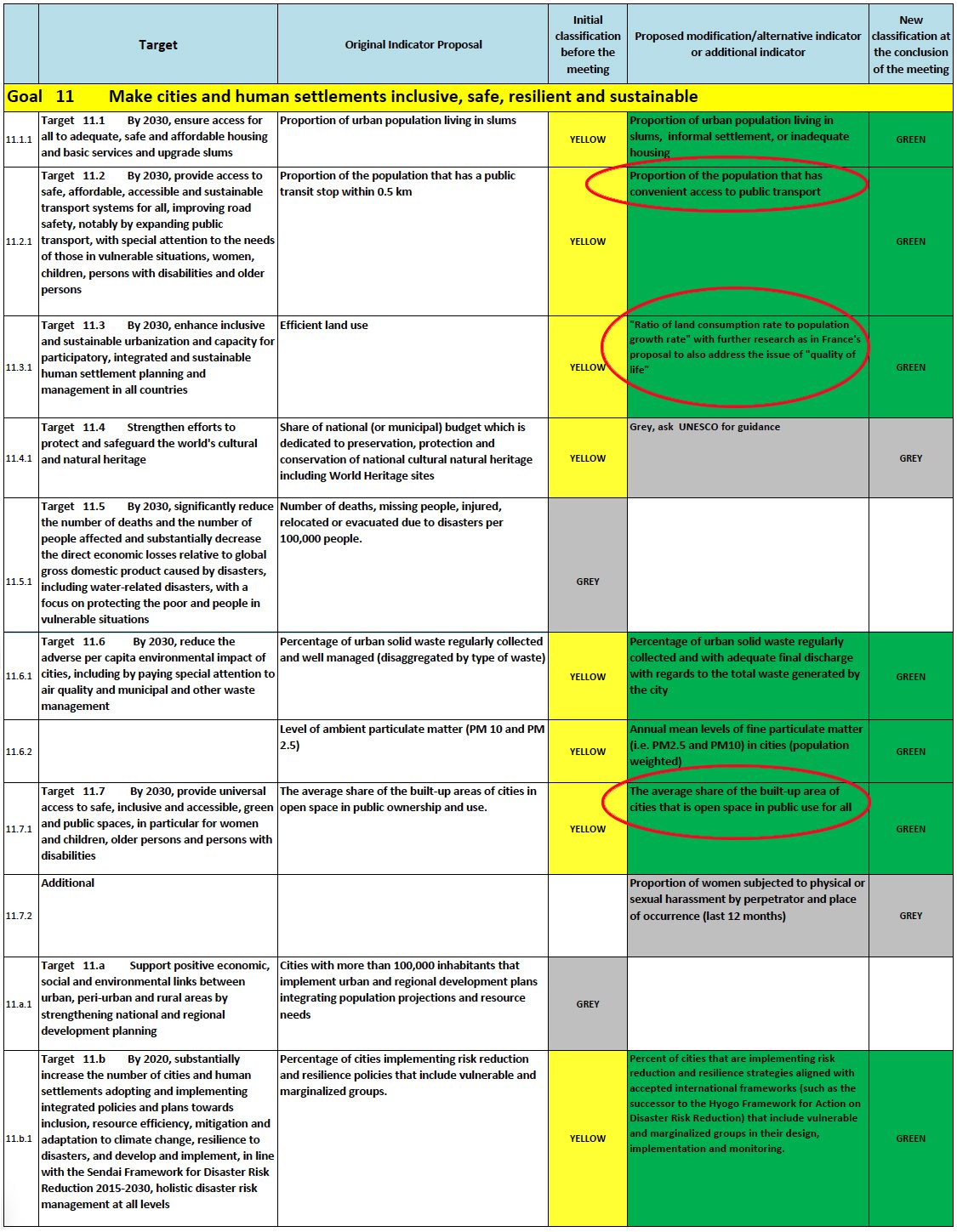

The UN Statistical Commission appointed an Inter-Agency Expert Group for the Sustainable Development Goals (IAEG-SDGs) to recommend a set of indicators for approval in mid-March. So let’s take a look at how the IAEG-SDGs is treating Goal 11, “Make cities safe, inclusive, resilient and sustainable,” and the seven associated substantive targets on housing, transport, planning, cultural and natural heritage, resilience, environmental impact, and public space. In November, the IAEG-SDGs met in Bangkok, Thailand to review a list of proposed indicators ranked yellow (caution) or grey (more discussion needed) and set about evaluating them, ranking them green (meaning ok to go) or grey. For Goal 11, six of seven proposed indicators held yellow classifications and one was grey at the beginning of the review. But by the end of the deliberations, five of the seven moved to the green column, one was grey (11.4) and one had no classification (11.5).

Now comes the hard part—activating the indicators. Three of these indicators are strong candidates for using new geospatial technologies in what could become a revolutionary way to bring policy-relevant information to public and private decision-makers.

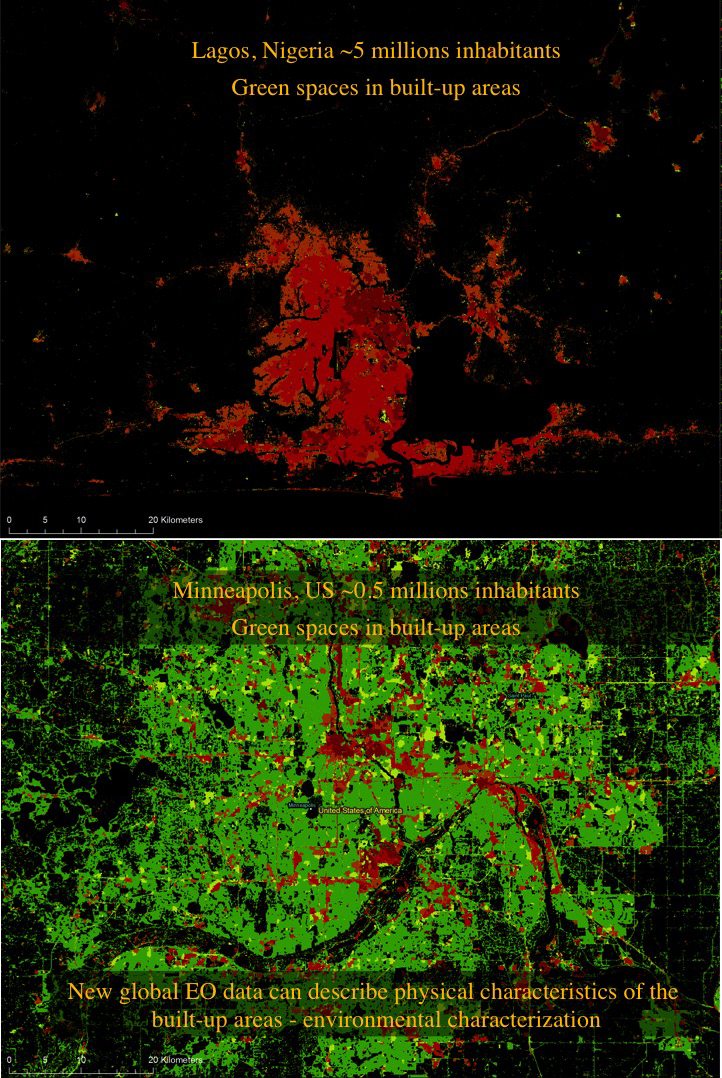

Two tools that can help overcome the monitoring obstacles: the Global Human Settlements Layer (GHSL) and World Pop. The GHSL, a project of the European Union’s Joint Research Council, is due to be fully launched in Fall 2016, coinciding with the Habitat III Conference, the first all UN conference to be held after the passage of the SDGs. The GHSL is a free, open source platform that maps the built up area of the entire world—it can produce national, regional and local maps. It can also monitor green space, as the two images below represent, by showing the inverse of the built up area, which can be used to calculate open space. For more information, see here.

While geospatial mapping identifies the presence of green and open space, it does not indicate public ownership and use. For that, according to UN Habitat’s Eduardo Moreno, who has extensively studied Goal 11 and its indicators, national governments will have to work with local authorities to collect the information. This will likely require developing a sampling method, searching city records for the appropriate information, and transmitting the data back to the national government unit charged with reporting.

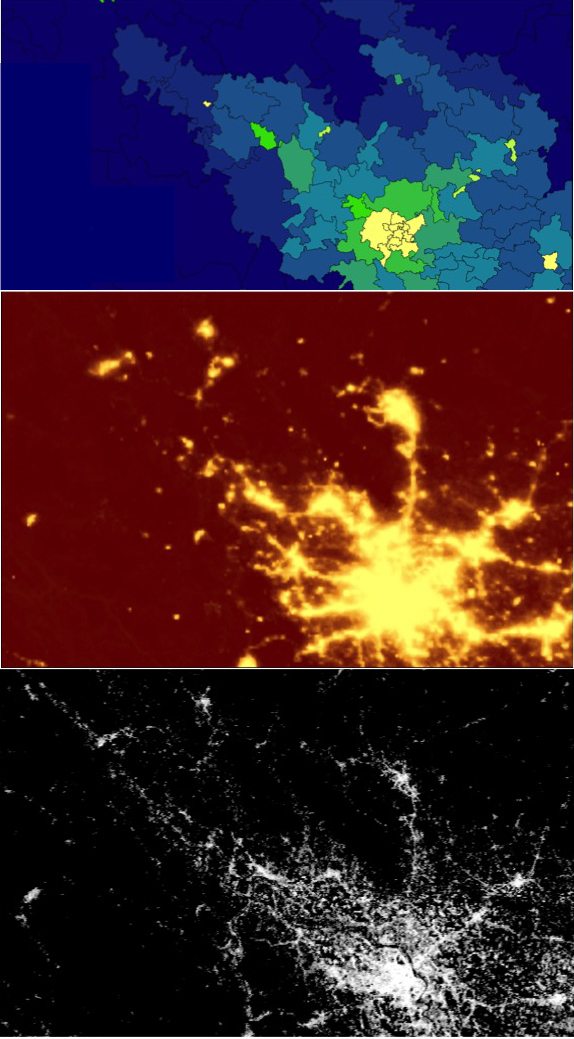

World Pop is a statistical application that, when applied with co-variates such as the GHSL, can demonstrate the location of population with greater detail than current assessments. The images below illustrate a progression of detail, moving from mapping census material by enumeration districts, mapping population data blended with Night Lights (one of the most well known of the current remote sensing applications often used to estimate population and economic activity [light means activity—a rough proxy]), and ending with mapping World Pop demographic assessments with the GHSL. For more information see here.

While these applications represent promising efforts in the emerging data collection front, one of the more immediate challenges will be to find ways to develop capacity in the public officials charged with reporting. This means education at national and subnational levels. In addition, work with civil society to communicate and translate the power of the indicators to guide decision-makers as they develop programs and policies in support of sustainable urbanization will also be necessary. It’s an exciting, challenging world out there!

References

Martino Pesaresi, “Global Human Settlement Data Use in the Perspective of SDG Monitoring,” presented at the GEO-XIII and 2015 Ministerial Summit, Group on Earth Observations, Mexico City, November 10, 2015.

Alessandro Sorichetta, World Pop and Flow Under Activities to Support the Sustainable Development Goals, presented at the GEO-XIII and 2015 Ministerial Summit, Group on Earth Observations, Mexico City, November 10, 2015.

about the writer

Ben Bradlow

Benjamin Bradlow is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology at Brown University. His research investigates the role of urban politics and institutions in processes of democratization and redistribution in Brazil and South Africa.

Benjamin Bradlow

The struggle embedded in the “Urban Goal”

The Sustainable Development Goals, which have now replaced the Millenium Development Goals, herald at least one major shift from the MDG era. No longer is a division posed between the “developed” and “developing” nations of the world. The SDGs are for all countries.

Long-standing divisions of the world economy and political relationships have posed spatial distinctions between East and West, or North and South. So it is interesting that one goal within this otherwise universal list makes a spatial distinction: Goal 11, the “Urban Goal.” In many countries in the “developing” world, a rural bias has been a common feature of post-colonial societies, in which urban populations are perceived to be independent-minded and critical of the excesses of post-colonial nationalist political parties that fall prey to what Robert Michels (1911) called the “iron law of oligarchy.” In the “developed” world, we have witnessed often extreme cycles of both public and private investment and disinvestment in cities, as elites oscillate between desiring the advantages of urban life and escaping its perceived dangers by moving to peripheral suburbs and fortified private enclaves.

All of this suggests that the key dimension to realizing the elements of the Urban Goal boils down to understanding how cities are governed. This is not merely a matter of institutional design, which is a common pitfall of universalistic policy debates. Rather, it is of paramount importance that we understand how governing coalitions effect change, and on what bases these coalitions are maintained and changed to continue carrying out transformative agendas. The constituent groups will not necessarily be exactly the same in each city.

Goal 11 concerns the degree of inclusion of city residents in accessing land, shelter, basic services, public transport and livelihoods. These are distributional issues, and, as such, they will be contested. The language of conflict-free “win-wins” in this regard is disingenuous, as distributive struggles are the essence of political institutions. Conflict is unavoidable. The SDGs cannot provide a blueprint for how to manage urban political relationships. However, they do help provide a touchstone for the normative principles that can underpin the assembling of the coalitions that can make these relationships a reality.

My hope is that when cities want to implement, for example, public transport programs that have worked in places such as Curitiba, Brazil, or Bogotá, Colombia, and which have frequently acted as touchstones for recent experiments with bus rapid transit in major cities in Africa and Asia, politicians and planners do not seek only, or even primarily, to emulate the technical engineering details of these programs. Rather, they must first ask, what kind of politics allowed this to happen? Which groups and individuals are important to its success? What conflicts arose? What kind of compromises were necessary?

Universalistic goals like the SDGs are, by their very nature, unable to capture the political difficulties of what is being proposed. By virtue of their need to navigate the sheer complexity of urban social relationships and built environments, those individuals and institutions charged with making the SDGs a reality will be undertaking what is fundamentally a political task.

So what can we do to make sure the opportunity of a rather impressive set of goals is not lost? I believe that it is up to researchers and policy analysts to highlight the political alignments and relationships that make policy possible. Earlier generations of urban planners were once thought of as “doctors” who prescribed fixes to the body of the city. But principles of design and engineering will mean little without an analysis of the political conditions that make governments either able to effect change, or that make governments crumble under the complexity of the urban palimpsest. This will constitute a substantive engagement with the needs of policymakers and planners, which does not treat universalized development goals as a technical blueprint, but rather as a set of norms around which to frame political relationships and institutions. It is up to people in cities, their organizations, and their institutions, to struggle to make these principles reality.

about the writer

William Dunbar

William Dunbar is Communications Coordinator for the International Satoyama Initiative project at the United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS) in Tokyo, Japan.

William Dunbar

“Inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”—this is the list the UN chose for headline attributes that cities should have. These are all good things, and the UN should be applauded for coming up with and approving this Goal. Of course, any list invites the reader to evaluate not only what is included, but also what is not. Some missing terms, such as “healthy” and “clean,” may be considered to be covered under the other list items, while other ideas, such as “having adequate public transport,” are mentioned in the longer description of the goal. One thing I would like to see not so deeply buried in the Goal 11 Targets is the idea of cities “integrated into the wider landscape.”

Integration into the wider landscape—this wording, which is used for protected areas under the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Aichi Biodiversity Targets (also at #11, coincidentally), is hinted at by “inclusive,” but the description of the goal seems to be oriented toward inclusion of disparate classes within the city. It is true that both extreme poverty and wealth are often concentrated in urban spaces. But the inequality between urban “haves” and rural “have-nots” can be even starker, particularly when cities’ role as one part of a connected and integrated landscape is ignored. “Haves” and “have-nots” in this case refer not only to material wealth, but also to access to the opportunities and services that cities offer.

It hardly needs to be stated how much cities typically rely on surrounding rural, semi-rural and peri-urban areas for provisioning, regulating and even cultural services, in terms of peoples’ biocultural ties to nature. But it is also important to consider what cities contribute to the wider landscape. They provide a place for many people to live, relieving population pressures on areas needed for production activities, and also provide markets for agricultural products, among other services. Cities’ policies that ignore vital urban-rural relationships can have negative consequences not only for the surrounding areas, but also for the cities themselves.

As an example, consider a city that traditionally gets its food from surrounding agricultural areas. Policymakers are generally also concentrated in urban areas, and some of these individuals enact policies to make foreign imports cheaper, thinking that cheaper goods will improve life for urban residents. Not only does shipping larger amounts of goods from overseas mean increased pollution, noise, etc., now rural residents, deprived of a market for their products, are forced to abandon their land and move to the city, exacerbating the very problems that the policy was supposed to help, including urban poverty. This type of mass urbanization and rural abandonment is happening in many places around the world, fed partly by urban-centric policies that are meant to improve city life, but ignore the city’s integration into the wider landscape.

If Goal 11 is to be met and cities made inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable, urban planning must take an integrated approach as the Goal’s description states—not only in terms of the different socioeconomic classes within the city, but also in terms of the city and its surrounding landscape. Much of our work with the Satoyama Initiative at UNU-IAS is in working toward policies that consider the landscape in a holistic manner, incorporating human settlements along with all other types of production areas. And if this is done in such a way as to maintain a healthy balance in urban-rural relationships, then cities may be able to have some of the other attributes not included in the UN’s list: “pleasant,” maybe, or even “enjoyable” and “a fulfilling place to live one’s life.”

about the writer

Peter Head

Peter is a civil and structural engineer who has become a recognised world leader in major bridges, advanced composite technology and in sustainable development in cities and regions.

Peter Head

The first thing that has struck me is that I have been monitoring social media since September 25th, 2015, when the SDGs were launched, and Goal 11 has not had anything like the same coverage as others, apart from the push by the Urban Campaign Group. I think this is because the Goal is mainly about integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management, which is a complex and inaccessible subject for young people, compared with poverty, water supply, energy security or infrastructure provision. The critical importance of urban-rural integration makes it even more complex.

This is, of course, why we had such a tough time getting the Goal over the finishing line, but we all know that the content of Goal 11 lies at the heart of the transformational change we need to improve human well-being and resilience globally. It will be transformational on performance and, as no one is doing it, there will have to be a transformation in every urban settlement in the world!

Communication about Goal 11 and its importance is therefore going to be crucial going forward—getting the Goal is wonderful, but we need to communicate its importance to the whole world if communities are really going to get behind it. This is likely to be the role of cities and urban settlements in achieving Goal 11, as part of their lobbying of national governments to get them to adopt urban development strategies and to dedicate powers and finance to deliver the outcomes.

The second thing that has struck me is how the rhetoric in the “cities community” in the middle- to high- income countries has barely flickered as a result of the Goal being adopted. For example, in the U.K., there is a Foresight program underway which is reporting on Future Cities and their material does not reflect the importance of Goal 11. If you go onto the Future Cities Catapult website and search for SDG Goal 11, there are no responses. It seems, in the U.K. at least, that the SDGs are for everyone else?

I think one of the reasons for this is that integrated planning is complex, involves engaging communities and is little used in practice, whereas technology and sensors and IT systems are much more accessible and interesting.

So I conclude that there is a major disconnect between the actual words and meaning of Goal 11 and the intentions of cities and the research community. All the city lobby groups and mayors were great in supporting its inclusion, but I wonder if the meaning of the words was really grasped.

So I conclude that there is a major disconnect between the actual words and meaning of Goal 11 and the intentions of cities and the research community. All the city lobby groups and mayors were great in supporting its inclusion, but I wonder if the meaning of the words was really grasped.

I went to a Future Earth meeting in Xiamen where this disconnect was discussed for China and the Asia Pacific Region and there was recognition (particularly from China) that co-design or integrated planning is really critical if the transformational change set out in Goal 11 and other Goals is to be realized. It requires an integration of social and natural science and economics in order to bring forward new tools to support capacity building for integrated planning and performance-based design.

It has been recognized that access to capital will be key to enabling these transformations to take place and this means making money available for research, planning, education and for projects. At this stage of knowledge and practice in integrated planning, there needs to be a big, fast application of money to research, planning and education that leads to capacity building and demonstration. Then, we need a massive scale up of that finance moving into city transformation using the money we know is available.

With this objective in mind, we are working very hard to develop a global funding mechanism to get money into integrated planning and performance-based design for urban-rural systems in which community participation and the economics of human well-being are embedded. What we need right now is a road map and mechanism for deployment of this funding, linked to the value this will create to society as trillions of dollars are moved successfully into delivery of Goal 11.

about the writer

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course on conserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and published a book, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

Mark Hostetler

Cities can play a role in conserving the world’s cultural and natural heritage

Looking through the ten targets under Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable, they essentially cover the three pillars of sustainability: social, environmental, and economic. I agree with previous conversations, particularly Yunus Arikan’s comments, that cities need solutions that are cross-cutting and holistically address social, environmental and economic concerns. I do think there are many synergies among the sustainability targets mentioned under Goal 11, but for simplicity, I’ll focus on one of the ten targets:

“Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage.”

A laudable target, but how do cities move forward to embrace urban biodiversity conservation and to conserve the traditions, values and practices of local cultures? I do think unique opportunities exist in cities to protect both cultural and natural heritage. Many cultural traditions around the world are rooted in the use and appreciation of native flora and fauna. Landscaping and/or conservation of native plants will not only help in terms of biodiversity, but it will present an opportunity for urban residents to retain cultural traditions and practices.

For example, in New Zealand, the Maori use the fibers of native flax or harakeke (Phormium tenax) to make a wide variety of items including baskets, fishing nets and traps, rope, and clothing. Incorporating New Zealand flax into yards, neighborhoods, and community parks presents an opportunity for city residents to harvest fiber and to create items that were traditionally made by Maori. In addition, the nectar from NZ flax flower is an important source of food for many nectar-eating indigenous birds, such as the Tūī and Bellbirds. NZ flax is habitat to a host of other animals such as arthropods, geckos and skinks that feed on or live in native flax. One can think of such cultural and natural synergies in any city around the world.

To create enabling conditions where native landscaping and conservation practices are implemented, I think the first step is to make city policies where decision-makers, from homeowners to developers, are rewarded for incorporating native plants and habitats into the urban landscape. This can take many forms, but I believe incentive-based policies that give a monetary benefit to landowners are the best way to encourage new practices. For example, developers could get a tax break, a housing density bonus, or a permit break when they landscape with native plants and/or conserve wildlife habitat for a development project. In these native plant and animal habitat areas, educational signage should be installed that describes how these plants and animals were utilized and appreciated by local cultures. At a smaller scale, homeowners could get a property tax break or a reduction of their utility bills when they landscape their yards with native plants.

Also, to kickstart citywide efforts to protect cultural and natural heritage, cities can create examples on their own properties, such as public parks, where portions of the parks are designed for local plants and animals. These areas could serve as cultural demonstrations where people can learn about traditional use and appreciation of native flora and fauna. This can take the form of interpretive signage or outside “workshops” where people learn how to utilize local plants, such as flax weaving done by the Maori in New Zealand.

I believe to move a city forward, we need model examples. Brainstorming between citizens, ecologists, design professionals and planners can provide a suite of practical ideas to help produce local examples. Nothing speaks louder than a local project where one can observe the areas that have been transformed. People can see it and envision how they could do it on their own property. Think of a homeowner that sees his/her neighbor remove the exotic turfgrass and install a butterfly garden that has native host plants for butterfly caterpillars and nectar plants for adult butterflies. Or a developer that sees his/her competitor building a conservation subdivision where the cultural and natural heritage is infused into the design and management of the community. Such examples begin to create a new “norm” for a city and would foster the adoption of novel design and management strategies that conserve cultural and natural heritage.

about the writer

Hui Ling Lim

As a Climate Reality Leader, Ling is dedicated to empowering others to step up and lead on sustainability.

Lim Hui Ling

Not having cities at the forefront would undermine the effectiveness of the ‘New Urban Agenda’

From the experience of the MDGs, global commitments can and have made a difference. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) #11, an explicitly ‘urban SDG,’ is a win for the global development community as it signals that we are finally paying due attention to the centrality of cities to the future of sustainable development. In a way, as soon as the SDG was adopted, it exceeded its use-by date. It has served the purpose of focusing attention on the importance of making ‘cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.’ Ultimately, however, we will be measured by how well we implement this SDG.

The next United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) in October, 2016, will be the first of the Habitat conferences to take place after the adoption of the SDGs. Aptly, the United Nations has promulgated that the conference is going to be about the ‘New Urban Agenda.’

Currently, even as the theme of empowering local governments is widespread in the discussions, there is still a focus on country-based national reports and on ‘National Habitat Committees’ in the preparation process for Habitat III. Local and regional governments are providing their inputs to the draft agenda, rather than driving it.

To be effective, the desired outcomes of the SDG have to be tackled at a localised level. From the agenda setting, to the design of the indicators and progress tracking, sophisticated local knowledge is a prerequisite. For instance, reducing urban environmental impact in Chengdu and in Prague could have different contextual meanings and would entail different approaches, with different emphases.

Considering the need for local expertise, and with city governments being most immediately connected to the people they serve, the urban level offers the optimum level of governance where public service and leadership interact with urban actors. Cities have the capacity to respond swiftly to local conditions with innovation, finance and appropriate solutions based on local resources. Good city leadership can corral resources from multiple partners, including from federal and state governments, private corporations and philanthropy, research institutions and sister cities.

There is already much talk about decentralised governance as part of the implementation of the New Urban Agenda. It might be worthwhile to bring the timeline forward; rather than centralise the negotiations and leave Member States to be the arbiters of what needs to be implemented under the ‘urban SDG,’ perhaps experiment by having cities and city groupings formulate the relevant implementation plans of the SDG instead. Relegating cities to the role of providing inputs to the New Urban Agenda is anachronistic. The governance of territories by city leadership has been evolving with the growth and expansion in economic power of urban regions. This is not a matter of Member States relinquishing their conventional roles in the international development negotiation process; it is more about recognising the reality of the ‘New Urban Agenda,’ where many cities are now the drivers of economic development, and are blazing the path in sustainable development, climate change mitigation and more; it is about harnessing the capabilities of an existing global constituency of cities, as a deserving and equal partner in delivering on the urban SDG.

Even at this stage of the agenda drafting period, Member States would benefit from bringing their cities into the inner circle of the preparatory process more by supporting Habitat III’s education and outreach efforts and ensuring that cities directly participate and take a more active role in defining their concerns and priorities and proposing implementation approaches for the urban SDG, both through the Habitat III regional and thematic forums and through other major international, inclusive platforms such as the annual World Cities Summit Mayors Forum.

If this unprecedented opportunity comes to bear, cities can avail themselves of bilateral cooperation and adapt from tried and tested approaches and the wealth of best practices that exist. There is no need to reinvent the wheel. At the Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC), based on our study of Singapore and other cities’ experiences, we have identified two very common factors underlying the successful transformation of many cities, from New York, to Bilbao, to Suzhou City, to others.

First, having a system of integrated planning is crucial, as it keeps the long-term targets constantly in view. Secondly, to make these plans into reality, the governance principles have to be inclusive, responsive and pragmatic, and effectively implemented by sound institutions embodying a culture of integrity. These principles have ensured that the conditions for the attainment of the desired liveability outcomes are well laid (See CLC Liveability Framework). With a holistic and long-range strategic implementation approach—we have until 2030—and with cities at the forefront as actors of change, we can certainly set high hopes to deliver on the targets of the urban SDG as well as the other SDGs.

To assist cities in achieving sustainable and liveable development and integrating the aforementioned principles of the Liveability Framework, the CLC regularly holds capability development programmes. These programmes are for city leaders interested in learning how to address the complex challenges related to rapid urbanisation and high population density. All cities are welcome to apply.

about the writer

Shuaib Lwasa

Shuaib Lwasa is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography at Makerere University. Shuaib has over 15 years of experience in university teaching and research working on interdisciplinary projects related to urban sustainability.

Shuaib Lwasa

The promise and pitfalls of SDG 11

Goal 11 of the SDGs has finally embraced what I think of as a holistic view of cities and human settlements, moving from the slum-improved target of the MDGs to include human settlements ranging from hamlets to megacities. The goal’s adoption as one of the 17 SDGs is a big step in recognizing the importance of human settlements and cities, which contain more than half of the global population, as conveyors of sustainability. But cities and human settlements have long been developed with models and frameworks that idealize ‘space,’ the ‘order of that space’ and the outcomes of such order.

Whereas these frameworks have worked in some regions of the globe, they have failed to deliver in others, including sub-Saharan Africa. This implies that working towards not only effective targets, but meaningful targets that are measurable, is the challenge of the communities concerned with urban development. This is because, despite the dialogues that went towards formulating Goal 11, the dominance of strategies that have previously determined the nature and trajectory of urban development inherent in the goal are clear.

For example, the underlying definition of access to safe and affordable housing and to affordable and sustainable public transport systems is underlain with uncertainty. It is a tough challenge to achieve the goal and targets, which are complex. The indicators for whether these targets have been achieved are also likely to be complex, since not one single indicator would adequately measure, for example, the reduction of per capita environmental impact of cities in terms of air quality and wastes, or the sustainable urbanization of and capacity for participatory, integrated human settlement planning.

Scanning the known and tested evaluation frameworks, there doesn’t seem to be an appropriate framework for monitoring such complex indictors. It seems as though the evaluation will have to embrace indices, which have a reductionist problem. The relations between goals make it even more challenging to send a signal that defines the resilience of cities and that would have some way to include risk reduction, climate actions, and poverty reduction, in all its dimensions as defined in Goal 1, but in cities specifically.

To achieve and evaluate Goal 11 will therefore require making resilience an actionable concept that is measurable, so that it becomes possible to address the inherent risks of taking action on climate and to deliver equitable development. This calls for alternative conceptual frameworks, methodologies, data and tools to measure progress in achieving Goal 11, among others. Sustainable development may be undermined by increasing risk and disasters and/or progress made so far in terms of development will likely be reversed by the increasing rate of climate-related disasters. Intensity of disasters notwithstanding, the case for extensive risk and associated disasters is a risk profile for much of Africa, and particularly for urban Africa.

There are synergies and tough choices to make to achieve resilient cities. These tough choices are potentially the basis for new conceptual frameworks, methodologies and tools for achieving the targets of as well as developing appropriate measuring indicators for Goal 11. Local specificities will play an important role, since the definition of ‘order’ as it is viewed in the global South now is different from the dominant frameworks of urban development. It is critically important to transcend output indicators by developing frameworks for outcomes that can be tracked through progress markers. These progress markers include but are not limited to the following;

- Green urban infrastructure with a range of sociotechnical solutions that have been tested after failure of single unified infrastructure systems

- Reducing urban risk—especially extensive risk and development-accumulated risk— and curbing losses

- Transforming production processes and infrastructure that creates opportunities for all social groups for inclusiveness

- Enhancing urban ecosystems and the possible range of ecosystem services dependent on locale specificities

- Conventional urban development interventions have largely failed to reduce urban poverty; thus, creating opportunities for the urban poor seems a plausible progress marker to transcend traditional output indicators

- A resilient city would have features that harness opportunities related to scalable resource efficiency, decentralized services and infrastructure, local employment and expanded markets and strategies that eradicate urban poverty

about the writer

Anjali Mahendra

Dr. Anjali Mahendra is an urban planner & transport policy expert working at interface of research & practice on issues dealing with cities, transport, climate change & economic development

Anjali Mahendra

The urban SDG is important because it emphasizes the salient role of cities in advancing sustainable development goals in countries and globally. With increasing evidence on the urbanization of poverty—i.e., the fact that poverty is becoming increasingly concentrated in urban areas around the world—the urban SDG holds promise as a vision that marries the twin goals of environmental sustainability and poverty reduction in cities.

Implementation of the urban SDG targets in many countries will be difficult, with some short term costs but long lasting economic, social, and environmental benefits. The targets of the urban SDG should not remain on paper, countries must redirect attention to cities, sign on to the targets, and ensure that policies and plans at multiple scales — national, regional, state, and local — are structured to enable progress towards these targets.

The urban SDG stands the greatest chance of being successfully implemented if helps create a vision for city leaders to work towards as they improve performance, not necessarily in comparison with other cities around the world, but in comparison with their own status at an earlier point in time. Measuring progress towards the urban SDG targets requires current data about gaps in access to urban services, households living in informal or substandard housing, city revenues and budgets, and other such indicators on which data is currently very limited in many cities, especially in the global south. City and national decision makers must prioritize collection of these data. Higher levels of government must design financial and other incentives for cities to improve performance in service delivery and be better accountable to citizens. The adoption of the urban SDG is a good start but decision makers must now commit to making choices that can lead to its successful implementation in cities around the world.

about the writer

Jose Puppim

Jose A. Puppim de Oliveira is a faculty member at FGV (Fundação Getulio Vargas), Brazil. He is also Visiting Chair Professor at the Institute for Global Public Policy (IGPP), Fudan University, China. His experience comprises research, consultancy, and policy work in more than 20 countries in all continents.

Jose Puppim

How to recognize the natural/planetary limits in urban policy making?

The UN Post-2015 Development Agenda has indicated some of the UN goals (SDGs) for the next 15 years in order to achieve plain human development for all, while keeping life-supporting systems intact for the next generations. Nevertheless, we are far from having comprehensive governance and policy mechanisms to transform urban development processes to achieve SDG 11 (and the other goals), though there are some promising initiatives we could learn from and try to use strengthen policy processes and outcomes. One of the fundamental issues we need to address for dealing with sustainable development is recognition of the environmental/planetary limits in policymaking at various different levels. We need to make huge transformations in the way we think about development processes and their governance.

We are slow to understand how to galvanize transformation towards more sustainable urbanization and to find alternatives to our current model of development, beyond recognizing that we need significant transformation in our governance systems. A shared starting point in the criticisms on the existing alternatives, such as green growth, is that efficiency strategies, which constitute the core of the ecological modernization discourses, are not a sufficient condition for leading to a broader transformation towards sustainability.

Moreover, the world is turning into a polycentric system of governance, but our local institutions and organizations have not adapted to this new system. Faced with this reality, we can point to changes in governance patterns, both in theory and in practice, that can move us beyond the technocratic realm and can help us to negotiate a more equitable future on a shared and finite planet.

There are three levels of transformation that may be required with different degrees of efforts, needs and uncertainties. Firstly, we need to move much faster in the transformative helms where we already have control and knowledge, such as use of appropriate, more efficient technologies and existing managerial tools, as well as establishing good public transport and land-use policies to avoid sprawl. But this is not sufficient. For example, China has made great advances in the production of renewable energy and energy efficiency. Still, these changes have not been able to offset the growth in energy demand in China. The second level is the decision-making and implementation systems that constrain broader transformative changes that would come with more balanced power, such as giving voice to different groups and making organizations, in the public and private sector, more accountable, as well as trying to coordinate efforts to identify synergies among networks in a polycentric society. Tokyo has established the first and one of the most climate-friendly policies. This was only possible after almost a decade of debates with policymakers in government and civil society. Now, the city is trying to incentivize other towns to do the same. Last is the ethical level, as we need a significant change in the values and beliefs of society that would lead to changes to the large institutions that shape most of our political and economic decisions. Bhutan has introduced the new idea of the Gross National Happiness index, which challenge the fundamentals of our thinking about development.

New insights from the recent advancements in the discussions on the Post-2015 Development Agenda and the possible climate agreement after UNFCCC COP-21 can potentially help to propel larger transformative changes at the different levels. Our capacity to accelerate the transformation we need rests necessarily on how to incorporate the concept of sustainable development into different governance systems, including urban governance systems, and to translate the decisions into results in practice. The SDGs represent a new attempt to transform our approach to development, including the planetary boundaries, but we do not have the governance to steer this transformation. The history of sustainable development is littered with well-intended but ill-designed or ill-executed initiatives. Our hope is that the urban SDG will not be one more among them.

about the writer

Karen Seto

Karen Seto is Professor of Geography and Urbanization at Yale. She is an expert on urbanization in China and India, forecasting urban growth, and climate change mitigation.

Karen Seto

We will build more urban areas during the 21st century than in all of human history. Simply stated, we cannot afford to create 21st-century cities with outdated ideas and technology. Yet, that’s what we’re on the trajectory to do if we do not transform the way in which we build new and rebuild existing cities. The Urban SDG has the opportunity to be a catalyst for changing how we conceive, design and manage cities. We need to urgently work towards establishing a plan of action for implementing and monitoring progress towards these goals.

How can we avoid these dangers? There is a long list of things that should be done, but there is at least one thing that must be done in order for the Urban SDG to be achieved and that is the coupling of strategies across scales. Many of the conditions, processes and policies that affect urban areas occur outside of urban areas, be it the political economy or regional or national contexts. Cities cannot achieve the goals of the Urban SDG if they act alone. They must have the support of regional and national governments and institutions. However, support is also not enough. Cities must work together to ensure that efforts undertaken at the local scale are not subverted by strategies at other scales or by other actors. This will require a lot of coordination and sustained dialogue among diverse institutions, leaders and communities.

about the writer

Andrew Rudd

Andrew Rudd is the Urban Environment Officer for UN-Habitat’s Urban Planning & Design Branch in New York, where he leads substantive advocacy for the urban dimension of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (including the SDGs).

Andrew Rudd

As with their predecessors, the SDGs will continue to bring attention to sustainability issues of global importance, encourage accountability from governments and (hopefully) attract financing. None of this is new, but that does not make any of it automatic. We, as an urban community, will have to enable much of it. In contrast to the MDGs, the SDGs are also set to tackle contemporary challenges, such as climate change, through contemporary, place-based approaches. The SDGs’ newly consultative formulation means greater stakeholder ownership. And their fresh focus on common but differentiated responsibility (CBDR) means that the developing world has as much stake in them as the developing world. (The upcoming agreement in Paris will show whether such an arrangement is feasible in practice.) These more novel aspects will also need our active support if the new issues’ metrics are to be consistently used, if cities are to actively engage in their implementation and if countries in all parts of the world are to take them seriously.

So what do we need to do now? The first thing is to help cities see why the SDGs (or the global development agenda at all, for that matter) matter. How do the million and one choices that urban dwellers make every day add up to the global consequences that ultimately return to impact them in local, personal ways? What to recommend to city dwellers whose choices are too limited in the first place to allow for sustainable behavior? How can they be encouraged to ‘do their part’ for SDG 11?

No doubt my colleagues on this panel will have articulated many of the catalysts for its implementation, from cross-sectoral partnerships to cross-scalar governance; from lowering the risk of lending to cities to increasing their ability to generate local revenues. All of these will be essential. Let me add something else: getting the balance between structure and agency right. Urban settlement patterns often limit choice to the point where populations have little alternative but to behave in unsustainable ways (e.g. living in a freestanding house and driving a private car). The developers of such patterns often claim they are accommodating residents’ demands. Residents sometimes claim that they never had a real choice in the first place. How to address this catch-22?

The targets of SDG 11 aspire to a number of structural improvements, but the critical role of agency in them is not always clear. To remedy this, cities can do three things: (1) help urban residents better understand the trade-offs inherent in particular settlement patterns (e.g. high-density, mixed-use over low-density, single-use); (2) get urbanites involved earlier in planning processes (e.g. planning for new urban areas or retrofitting existing ones); and (3) incentivize and advocate for better personal choices (e.g. cycling over driving). Understanding the consequences of personal choices may lead city dwellers to demand more responsible choices from others, and ultimately to demand that the system itself provide more choices in the first place.

The NGO Transportation Alternatives, an advocate of nonmotorized transit infrastructure in New York, recently had an internal debate after another city motorist had struck and killed a cyclist. In this debate, a number of Transportation Alternatives members argued that continuing to advocate for a modal shift to more cycling was premature without more extensive, protected bike lane infrastructure in the first place. An opposing group argued that such advocacy had no credibility until a critical mass of cyclists could first demonstrate the demand for such infrastructure. Ultimately the consensus was ‘both.’ In other words, behavioral choices generate demand for structural improvement that prompt further behavioral change. (It is worth noting how such an intervention would contribute to the implementation of multiple SDG 11 targets: 11.2 on public transport provision, 11.6 on urban environmental impact and 11.7 on accessible public space provision, as well as 11.3 on making density more livable and 11.b on policies for accessibility, resilience and sustainability.)

With SDG 11, cities have their work cut out for them. To effectively balance structure and agency over the long term, key urban stakeholders will need to (re)configure themselves. In an earlier piece on the pedestrianization of Times Square, I wrote that residents need to contemplate and agree on common values. City leaders need to contemplate value-based priorities and execute and maintain a related vision. And enforcement bodies need to prepare to humanely and consistently guide the change inherent in any new vision. The sustainability battle we are fighting is a granular one, and it will not only be won or lost in cities, but by cities through a million different decisions; decisions that both reinforce and challenge the very structure that guides them. The implementation of SDG 11 could be very exciting indeed.

about the writer

David Simon

David Simon is Professor of Development Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London and until December 2019 was also Director of Mistra Urban Futures, an international research centre on sustainable cities based at Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

David Simon

As a member of the Campaign for an Urban SDG, Mistra Urban Futures conducted a unique pilot project during the first half of this year, using its four transdisciplinary co-production research platforms in Gothenburg, Greater Manchester, Cape Town and Kisumu, along with Bangalore, to test the draft set of targets and indicators formulated by the Campaign and the UN statistical team up until that point. The extensive and detailed work of the Campaign has hitherto been undertaken in isolation from the daily pressures and realities of urban local authorities and other agencies that will be required to collect, compute and report on the indicators.

Compared with world or megacities, for instance, the five cities that formed the testbeds for this study—namely Bangalore, Cape Town, Gothenburg, Greater Manchester, and Kisumu—constitute a reasonably representative sample of the multitude of urban areas worldwide that will be faced with the new challenges of annual urban SDG reporting from 2016 forward. The precise extent of such responsibilities will vary by country in terms of how national reporting agencies allocate roles, but the specifically urban focus of most of the indicators makes some urban involvement inescapable. Indeed, this is part of the novelty and added value of Goal 11.

Our project examined the extent to which the required data already exist in accessible forms in the five cities and could thus be reported straightforwardly; which variables could be obtained or computed with relative ease, hence imposing only a small new burden; and which were unavailable without purposive primary data collection exercises.

If the urban SDG is to prove to be a useful tool to encourage local and national authorities alike to make positive investments in the various components of urban sustainability transitions as intended, then it is vital that it should prove widely relevant, acceptable and practicable. Otherwise, reporting will become piecemeal or irregular, data will be fabricated to suit perceived political advantages, or compliance with reporting obligations will become the principal objective rather than utilising the reporting as a stimulus to promote positive change towards urban sustainability.

It is noteworthy that not one draft indicator was regarded as both important or relevant and easy to report on in terms of data availability. Since the targets and indicators are supposed to be forward-looking and setting the agenda for the next 15 years, the overall consensus of the local authorities participating in this study suggests that for these to become useful and implemented at a city level, they must be relevant for local policymakers. Hence, they cannot be too few and general in scope and range, while there is a clear dilemma in striking a balance between reducing the number of indicators and increasing the policy relevance. There is also a clear discrepancy between the call for international standards on the one hand, and local realities on the other. This will not be easily bridged.

The project results made an immediate impact on the Campaign’s work and were made available to the UN statistical team for their current phase of finalising the targets and indicators. Once the SDGs are implemented, the Campaign anticipates an ongoing need for monitoring, targeted training/capacity building in urban local authorities in poor countries, and probably some revisions to the initial indicators—much as has happened with the MDGs. Mistra Urban Futures has volunteered to play a key role in this process as a critical friend, since we believe that urban areas and their inhabitants worldwide will be better off and more sustainable with Goal 11 than without it. Indeed, this has formed the basis for the entire Campaign.

A paper summarising the project will appear in Environment and Urbanization 28(1), April 2015 but will be online during December 2015. The project reports are available at: http://www.mistraurbanfutures.org/en/pilot-project-test-potential-targets-and-indicators-urban-sustainable-development-goal.

about the writer

Bolanle Wahab

Bolanle Wahab, PhD, is a Lecturer and Researcher and former acting Head of Department of Urban and Regional Planning and also the Pioneer Coordinator of the Indigenous Knowledge and Development Programme at the University of Ibadan in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Bolanle Wahab

Urban SDG #11 is a good goal, but for us to get things on the right track, especially in the developing world, this goal cannot be isolated from the other 16 goals. Of great importance are Goals 1 and 3: (1) End poverty in all forms everywhere, and (3) Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, respectively.

For SDG #11 to succeed, indigenous knowledge systems and practices of peoples and communities in different nations and regions of the world must be given adequate recognition and attention. The range of issues to which indigenous knowledge systems can contribute is broad, including sanitation; urban planning and development control; climate change and disaster risk management; solid waste management; informality in planning; slum rehabilitation; new housing projects; urban greening and landscaping; and urban and peri-urban agriculture; and more.

Most ancient towns and cities in Africa, for example, had no master or development plans drawn-up in planning studios; yet, these settlements developed in an organised manner through the active involvement and collaboration of all stakeholders. The siting of structures (buildings, footpaths, tracks, open/recreational spaces, markets, community halls, village square, wells etc.) was done consciously, in relation to one another. Inclusive community planning was employed, whereby physical developments were controlled and monitored to prevent incompatible land uses and developments on flood plains, wetlands and disaster-prone areas, thereby promoting safe and resilient settlements. The tool or approach used throughout was indigenous knowledge, the systems of accumulated local knowledge and practices constructed and applied by local people and communities in the course of their everyday interactions with their living and working environment. Contemporary settlement planning knowledge has abandoned this system and the result is the chaos that is the experience of many African cities.

It will be key to include the participation of “ordinary people” and indigenous communities through the integration of their knowledge, attitude and practices in policy formulation and execution at all levels of government. A shift in the planning paradigm is required; let the people (irrespective of social, economic, cultural and political class/status) be part not only of planning and implementation, but in setting the goals and thereby setting the standards for the creation of inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable human settlements—the aims of SDG #11. In this way, project beneficiaries will be effectively engaged, will exhibit a sense of ownership, and will ensure project sustainability and capacity for replication.

Although local people may be low in formal western education, the knowledge systems and practices that have sustained their needs and aspirations in their environment over time are nevertheless very relevant for more formal settlement planning process. Such practices are still very dear to them. Their knowledge and modes of thinking, participatory decision-making, and the ways they implement programmes and projects should be integrated into the framework for implementing the urban SDG #11. Local context is critical.

By missing out on key information and strategies that are part of indigenous knowledge systems, SDG #11 could go badly wrong, especially in Africa. . It is even segregatory, discriminatory, morally wrong and against the principles of equity, justice and fair play to not include them. This is more so that the peoples’ roles and services are made indispensable in the social and economic development of any village, town or city. Under SDG #11, settlement planning should focus on making city life more accommodating for the poor through more compact development with adequate infrastructure and minimal risks; urban regeneration with adequate public spaces, and accompanying greens, especially in tropical regions; and creation of employment opportunities which incorporate cultural values. Exclusive developments, as in most African capitals, should be minimized. Population shifts to urban areas could be minimized through the enhancement of living standards in rural areas while discouraging/reducing urban sprawl and its effect on the available land for agriculture.

about the writer

Lorena Zárate

Lorena Zárate is co-coordinator of the Global Platform for the Right to the City and former president of the Habitat International Coaltion.

Lorena Zárate

The inclusion of an explicitly urban Sustainable Development Goal inside the Agenda 2030, adopted by the UN General Assembly last September, can be seen as an important step forward if compared with the Millennium Development Goals. But at the same time, it raises some of the same concerns—and new ones too—related in particular to the lack of an explicit human rights approach and the associated state obligations.

From our point of view, here some particular concerns:

a) In tracking the access to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services, special attention should be paid to the current national and local policies for rehabilitating and increasing the social housing stock, the level of protection for tenants (including those living in so-called informal settlements), the support of social production of habitat projects and the programs to address homelessness. At the same time, mandatory data collection of privatization of public/social housing and an inventory of the stock of available vacant buildings/land and abandonned/subutilized facilities and community infraestructure should be part of the equation.

b) UN-Habitat’s current, broad definition of “slum” and “informal settlements”—that involves the lack of secure tenure, access to basic servicies, sufficient living area, durable housing and non-hazardous location—will not be instrumental in identifying the specific problems that need to be addressed in different national and local contexts. The indicator should be disaggregated in order to get more precise information about each of the five mentioned characteristics.

c) As for the “security of tenure” component, it should include data on cases of harassment and forced evictions and displacements, as defined by international human rights instruments.

d) Affordability of both housing and public transport system (including integrated multimodal and non-motorized/non-carbon-related options) should be measured in relation to the real evolution of basic income and purchasing power of the households.

e) Although the word “participation” is mentioned few times in some of the specific targets, there is no explicit mention of the need to democratize decision making processes and put in place and/or strengthen the institutional spaces and tools for a truly democractic management of the territory. The development of indicators should actively solicit input from civil society and social movements who are effective in participation processes, and include their ideas in the implementation and monitoring of public policies and budgets at local, metropolitan, regional and national levels.

f) In protecting and safeguarding the world’s cultural and natural heritage, indicators should track the percentage of the local/national budget that is being managed by indigenous people and other ethnic and minority groups, who preserve biodiversity and promote social diversity and multiculturalism.

g) The promotion of the use of local materials and traditional building techniques should be a priority for building sustanaible and resilient communities. This will require a revision of the current global and national statistical data collection that frequently characterizes such methods as “precarious,” “informal” or “irregular,” or not in compilance with the construction regulatory framework.

It is clear that we have many challenging tasks ahead. As we can see, many of the targets are multidimensional and their appropiate measurement will require more than one indicator, and often composite ones. At the same time, given the prominent role that cities will play in monitoring progress, adequate technical and financial support should be available both for governamental and non-governamental institutions for doing so. Finally, stronger intersectorial and interactoral coordination will be necessary in order to address the SDG11’s commitments.

The contents for a “New Urban Agenda,” to be adopted at the upcoming UN Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III, Quito, October 2016) are now being discussed inside a complex and intense process. For that to be, at the same time, ambitious and operative, we should be looking at deepening the debates and filling the gaps from the experiences and proposals for the Right to the City that social movements, civil society and local authorities are putting forward.

Dear David (Simon),

Thanks for your comments. The big challenge will be to find the proper variables to assess all the targets/indicators (not only for SDG11, but for all the others). Some goals are very abstract. I am discussing how to make a SDG11 assessment with three cities, and it is really hard to define the proper indicators. For example, one goal related to our paper (urban-rural disparities) is:

“11.a Support positive economic, social and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning”

This could mean almost anything. One concrete example is the discussions in one of the cities. Someone suggested that having a plan to support the “move of economic activities from the city to the rural areas” you may be accomplishing with the goal, but this move can lead to urban sprawl in the long term (with all its consequences) or even create economically decadent inner cities (like in many urban areas in the US, though there was no such regional planning).

Jose

Thanks for these comments, Mark and Jose. The purpose of the pilot project was to figure out how viable the draft targets and indicators are, and what needs modification. This work is still going on in the UN statistical team and the final versions will be announced in March. It seems that many have now been agreed/finalized as incorporating feedback from the project among numerous other sources of political and technical feedback.

The indicator on green space is – like many – complex and in the Campaign workshops we debated precisely the points you make, Mark, and sought to come up with something straightforward to do yet fairly meaningful. Remotely sensed imagery can, for instance, enable ready identification of open/green space but not what quality and especially not what rules of access/exclusion apply – and the most relevant for leisure/recreational purposes rather than biodiversity conservation alone, is publicly accessible open space. Of course, there are also various intermediate categories – hence the challenges.

Jose, good to know of your new article – the points you make are accurate – and that is one key reason why the historical basis of UNFCCC climate change negotiations has had to shift to reflect the much wider range of countries (and key cities in them) with heavy GHG per capita emissions.

Best wishes for the festive season and a lower carbon 2016!

quite an informative article

I was very interested in David Simon’s piece and report regarding a city’s ability to monitor and report under the urban SDG. “It is noteworthy that not one draft indicator was regarded as both important or relevant and easy to report on in terms of data availability.” I also find that cities do not have the capacity to monitor and report many sustainability indicators. David, I glanced at the report – was there any indicators and strategies that would make the urban SDG relevant to many cities and governments would be able to report progress?

Urbanization is more correlated with carbon emissions than GDP per capita*

What are the implications of this statement for the SDG 11 and inequalities? It is particularly relevant to the points some of you made about the urban-rural divide and the need of decentralized governance. An article that just came out in Urban Climate* analyzes the urbanization, GDP and emission trends in more than 200 countries over six decades. It shows that urbanization is more correlated with carbon emissions than GDP per capita, shifting more and more the discussions to the urban-rural divide in LDCs. Thus, our study argues that existing dualities in the international climate change governance, evident in the so called global ‘North–South’ economic divide, has also a stronger component of local ‘Urban–Rural’ spatial disparity in the making. This is likely to further precipitate into a much local but complex dynamic, particularly relevant to the developing world, that face the double challenge of rapid urbanization and environmental sustainability. Cities in middle income developing countries emit as much as, or more, carbon(eq) per capita than many cities in the rich world and those countries present a large inequality urban-rural per capita emission (inequality which generally reflects in income as well). Thus achieving the SDG in cities in urbanized or rapid urbanizing developing countries is key for also reducing rural-urban inequalities in those countries, and globally.

*Source: Sethi, M. and Puppim de Oliveira, Jose A. (2015). From global ‘North-South’ to local ‘Urban-Rural’: A shifting paradigm in climate governance? Urban Climate (Elsevier). 14 (4) 529–543. DOI: 10.1016/j.uclim.2015.09.009

Implementation and monitoring progress for this urban sustainable development goal is going to be difficult but tools are available. I concur with Genie Birch’s comments regarding the use of geospatial technologies to monitor the growth of green space in cities is one way to demonstrate and enable cities to create strategies to conserve green infrastructure. I might add that all green space is not created equal and there is a gradient from manicured open space (i.e., lots of turfgrass) to more natural open space (i.e., structurally diverse with native vegetation). It is possible to rank various open space areas this way and maps could be generated where the natural heritage of an area has been conserved and where people can experience local flora and fauna.