A review of Towards Low Carbon Cities in China: Urban form and greenhouse gas emissions, edited by Sun Sheng Han, Ray Green and Mark Y. Wang. 2015. ISBN: 9780415743310. Routledge, New York. 216 pages. Buy the book.

Urban morphology has a great impact on greenhouse gas emissions, a viewpoint supported by research findings. Generally speaking, an urban form featuring disordered sprawl produces more CO2. Scattered urban land use increases travel distance, vehicle-miles driven, and per capita living space, which leads to more energy consumption. Low density urban development needs more infrastructure and public services for support, which increases carbon emissions, and the conversion of large amounts of relatively lower carbon emitting agricultural land into urban areas enhances carbon emission intensity.

Urban morphology has a great impact on greenhouse gas emissions, a viewpoint supported by research findings. Generally speaking, an urban form featuring disordered sprawl produces more CO2. Scattered urban land use increases travel distance, vehicle-miles driven, and per capita living space, which leads to more energy consumption. Low density urban development needs more infrastructure and public services for support, which increases carbon emissions, and the conversion of large amounts of relatively lower carbon emitting agricultural land into urban areas enhances carbon emission intensity.

Over the past three decades, China’s rapid urbanization has boosted economic development and brought about fundamental social achievements. However, this process has also been characterized by disorderly urban land use which has negatively affected the natural environment and drastically increased the carbon footprint of the country.

“Towards Low Carbon Cities in China: Urban Form and Greenhouse Gas Emissions” comes at a time when climate change is starting to be recognized as an important global issue, and the Chinese government is committed to exploring and implementing a low carbon urbanization pathway. The book explores the relationship between urban form and greenhouse gas emissions in China, and examines how factors such as urban households’ access to services and jobs, land use mixes and provision of public transport impact greenhouse gas emissions. The book draws on the results from a four-year multidisciplinary Australia-China collaborative research project, and is drafted by faculty members and students of renowned universities from both countries.

It is structured in three parts and ten chapters. The first part gives an overview of the book (chapter one) and introduces the policies and practices of low carbon cities in China (chapters two and three). The second part is the major component of the book. It examines the relationship between urban form and greenhouse gas emissions at a macro level (chapter four), presents results of analyses and empirical evidence related to the relationship between urban form and CO2 emissions in the four case study cities (chapters five, six, seven and eight), and reports results from household surveys from two of the case study cities with regard to the residents’ personal opinions on how to build low carbon cities (chapter nine). The third part summarizes the findings and discusses the implications of the outcomes of the research (chapter ten).

The book adds value to the existing literature in the field by filling in the research gap between greenhouse gas emissions and urban form. In China, research on low carbon cities is focused on the three major areas of carbon emissions: industry, transport and building. Though it is equally, if not more, important, the influence of urban form on greenhouse gas emissions usually receives less attention because it is much more difficult to quantify and evaluate greenhouse gas emissions associated with urban form. This research adds to the methodology in the field and offers a different angle to address the problem. It uses household survey results and transforms the information into quantifiable data, so that the relationship between urban form and household carbon emissions can be roughly evaluated. Empirical study and household survey make the research more realistic.

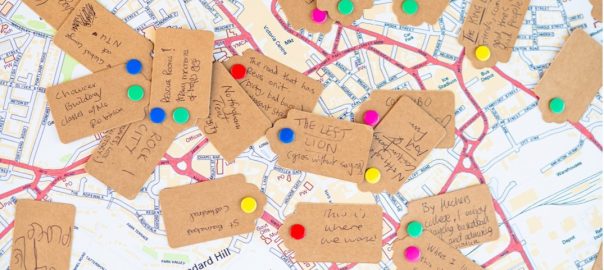

There are few empirical studies on the relationship between urban form and greenhouse gas emissions in China. By surveying 4,677 sample households from four major Chinese cities—Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan and Xi’an—the authors are able to analyze real life data and to draw practical conclusions. In addition, by conducting door-to-door household surveys in Xi’an and Wuhan, the authors are able to understand what the citizens really need and to have the local people’s suggestions for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This bottom-up approach is supplementary to the top-down mechanism dominating the decision-making process of low carbon cities programs in China. This research also shed light on the relationship between household characteristics and household daily travel carbon emissions. Factors such as household income, the level of education, type of employment and the family members’ travel behaviors are found to influence the household’s decisions about private car ownership and daily travel mode which, in turn, impact household carbon emissions. This research finding suggests that, in making urban policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as proper physical planning and design, policy makers and urban planners should also take these socio-economic factors into consideration.

As it is introduced in the preface, the target audience of this book is scholars, urban policy makers and planners. In my opinion, the book is obviously focused on research, and it might be more suitable for scholars and urban planners working in this field. It is strong in analyzing data and presenting research findings, but relatively weak in giving specific recommendations. For example, what kind of policy tools can Chinese local governments use to reduce greenhouse gas emissions associated with urban form? What is the specific roadmap to achieve this goal? How should the Chinese local executors act to make it happen? Further, the content and style of this book is research oriented. If we aim to influence policy makers, it is important to make it easier for them to read. City officials usually have little time to read a book that is theoretically rich; rather, they would be interested in a work that advises them on how to act. They love straightforward recommendations, hands-on experience and practical cases with vivid presentation styles (illustrations and tables).

I recommend this book mainly to urban scholars and planners. It is a timely product by contributors from multidisciplinary backgrounds (urban planning and design, urban geography, regional economics, public policy, etc.), and it succeeds in conveying its key message to its intended audience: urban form does influence greenhouse gas emissions, and cities with different spatial layouts vary in their average daily travel carbon emissions. But to bring this critical observation to the actual planning of Chinese cities, we will need an additional volume that elaborates on explicit recommendations and action roadmaps for local governments and implementers.

Pengfei Xie

Beijing

You can support TNOC (and the book’s authors) by buying the book via this link.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation