Edward Lorenz’s application of chaos theory to weather forecasting is better known to the general public as “the butterfly effect”, thanks to his conference presentation, “Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?” Lorenz’s law explains to us that there are unknown and invisible (to us) chains of interlinked effects such that any small variation in a system can induce big changes in the long term. One of the meanings of this idea is the assumption that real word phenomena are too complex to be explained or to have their consequences forecasted through simplistic, cause-effects dynamics. In this sense, any small decision can influence the long chains of interactions which will constitute the big picture we see.

While I’m writing this, I’m in an organic restaurant in Barcelona, in front of a quinoa salad. I know I’m the final consumer placed at the end of a long food chain.

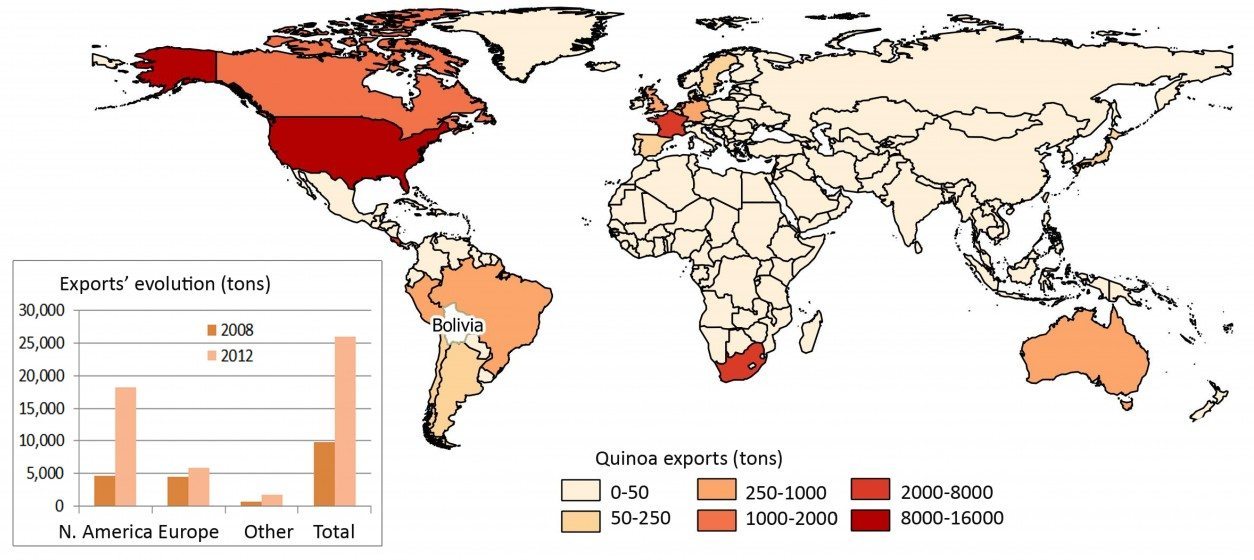

Maybe some readers already know, or remember, the incredible wave of newspaper articles on quinoa in 2013, when the United Nations General Assembly declared 2013 as the International Year of Quinoa. For a few months, dozens of authors wrote about this super grain’s healthy, beneficial effects. Others complained about quinoa farming’s dramatic environmental consequences in the remote areas of developing countries, where it is produced. Others talked about how it was driving prices up so that Andean people could no longer afford it.

Then, silence.

This is our social attention span.

I’d like to share with you some thoughts on the relationship between consumers choices in cities and the related, emerging resilience and vulnerabilities trade-offs, which link far-flung territories. By resilience trade-offs, I refer to different leverage mechanisms by which increasing resilience in one place could lead to increasing vulnerability in other far-away places, due to unclear, enchained effects. By doing this, I want also to challenge both the negative bias of vulnerability and the positive one of resilience. How does the butterfly effect relate to this? Stay with me: there is something to learn about resilience, vulnerability, and cities from the quinoa revolution.

But what is the quinoa revolution?

Quinoa (but it could have been Ethiopian teff, the next super-grain, or coconut water, or oil palm, since quinoa just serves as an example) is a highly nutritious grain-like crop cultivated by the farmers of the Andes for over 7,000 years, mainly for subsistence purposes. This “peasant food” has adapted to grow under the most harsh environmental conditions (drought, salinity, hail, wind, frost) and is the only vegetable food that possesses all of the amino acids essential to humans. However, it has never had any market or commercial value. Or, at least, not before the 1980s. In fact, in 1983, the establishment of the National Association of Quinoa Producers, or ANAPQUI, and, a few years later (in 1986) the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ identifying quinoa as a strategic food for the Andean region, contributed to launching quinoa in the regional and Latin American markets. As a result, in 1996, FAO acknowledged the nutritional importance of quinoa and catalogued it among the promising crops of humanity and, along with other underutilized food crops, as a potential solution to human malnutrition. Recognizing quinoa as a highly nutritious food caught the interest of American and European consumers. Today, quinoa can be found in any organic shop of any global city.

Vulnerability and resilience trade-offs

We could review the wave of scholarly and press articles presenting the general public pros (health effects) and cons (environmental degradation in Bolivia, or equity concerns regarding access to productive lands) of such a crop market boom. However, to me, this is not the most interesting issue. If you want to get to why, in cities, we should be aware of such cross-scale food market phenomena, you should take a step beyond the simplistic perceptions linking environmental degradation in Bolivia, food market speculations, and increasing quality of life in rich cities. From globalization, from the virtual shrinkage of distances and the related increased links among very faraway territories, emerges a complicated (and very dynamic) cocktail of opportunities and threats for both producers and consumers. The quinoa revolution falls into a category of opportunities that could empower both producers and consumers, building resilience into the food system. But such a rosy outcome is only theoretical, not realistic, given that new adaptations to these opportunities create new power dynamics and, inevitably, winners and losers.

We have become used to seeing resilience as a positive set of adaptive capacities (mainly related to diminishing risks and adapting to climate change or natural hazards), and vulnerability as the danger of been exposed to risky situations. Also, we have been told that increasing resilience corresponds to a proportional decrease in vulnerability. This is, generally speaking, true, and it does make sense. However, it is also too simplistic and not always adequate for describing our complex, hyper-connected, and fast-changing circumstances. In this regard, myself and other scholars have been recently working on emphasizing the policy nature of resilience (see these links for stepping from the classic ecological issue of “resilience of what to what”, to the critical geographers concern of “resilience for whom” and the “politics of resilient cities”). The emerging concept of “resilience trade-offs” explains such cross-scales and cross-systems leverage mechanisms between resilience and vulnerability, proposing that resilience, per se, is not always good, nor vulnerability bad. Increasing vulnerability to environmental degradation (take the case of quinoa mono-cropping, for instance) could indirectly mean increasing a set of capacities boosting well-being, knowledge, connections, and new development trajectories.

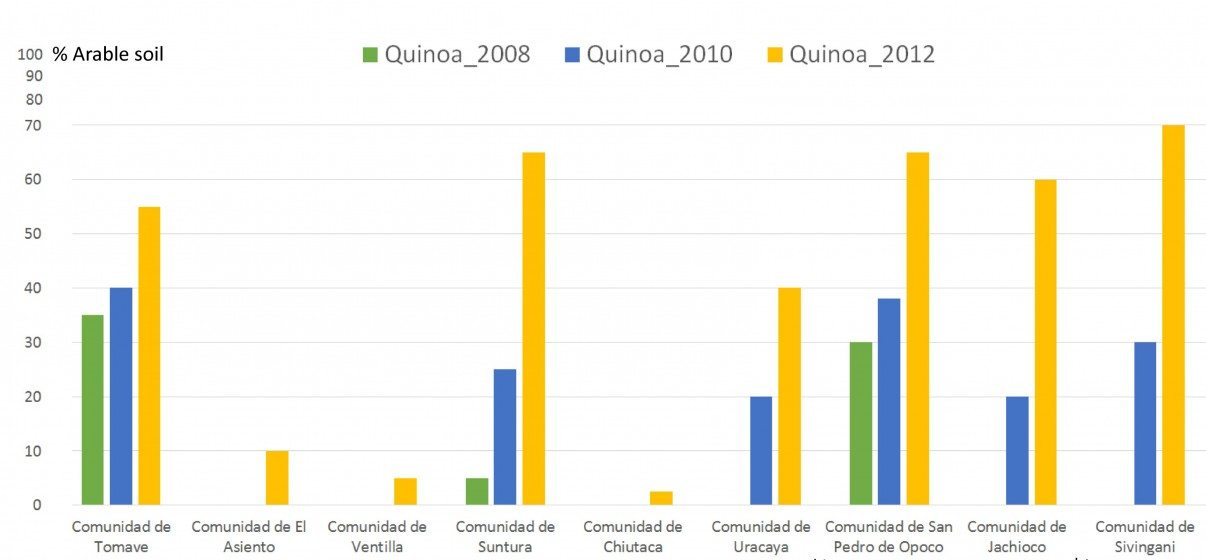

Take a look at Figure 2. These are very tiny villages, placed in remote areas at more than 4,000 m above sea levels, that have survived harsh climatic conditions for millennia. In order to survive these extreme climatic conditions, locals must know how to perfectly manage local resources, without eroding soil fertility or threatening groundwater reservoirs. Figure 2 explains the astonishing growth of quinoa-cropped lands in just 4 years, which in some cases now occupy most of the available arable land of the municipalities.

Can you imagine what this food market boom implies for such rural villages from the perspectives of ecology, socio-cultural changes, regional population movements, infrastructural building opportunities, emerging technological solutions, and multinational partnerships?

In a recent study, I’ve addressed these complex consequences with my colleagues Guido Minucci and Eirini Skrimizea. The results of our five years of observations were:

- a specialization of villages in (and a general increase of) llamas and sheep livestock, since the manure is used as the main fertilizer for quinoa in accordance with traditions and organic farming requirements;

- emerging technological and mechanical innovations related to the use and management of water and to emerging national and international partnerships with NGOs;

- increasing internal (regional) mobility and skills related to marketing strategies to diversify quinoa crops;

- generational behavioural changes, which are both generating shocks among groups (urban versus rural people or different villages) and re-framing land-tenure rules, challenging the traditional common management of the lands.

While adapting to global food market stimuli brought Andean farmers a set of benefits and emerging capacities, we also observed a simultaneous increase of new threats and stresses, such as:

- the previously unknown risk of “water scarcity” (because of the intensive cropping and breeding);

- increasing social tensions and conflicts;

- increasing dependencies on external markets and mono-cropping (exposure to economic failure because of lack of diversification);

- increasing losses of rare ecosystems and biodiversity; and

- the loss of traditional social capital and cultural landscapes.

Can you get a clear picture, from this transition, of whether the Andean farmers are now more resilient or more vulnerable?

A simple answer is that they are no longer exposed and vulnerable to hunger and isolation, since they are no longer completely dependent on natural and climatic processes, as they were used for millennia. However, one of the side effects of this transition is that they are now entirely dependent on exogenous markets dynamics.

We don’t know if the quinoa market boom—which is threatening the Bolivia Altiplano fresh-water reservoir and biodiversity, apparently increasing villages’ vulnerability to climate change—is definitely a bad thing, or if these increasing vulnerabilities are temporary side-effects of establishing the basis for a development revolution in which locals will truly benefit in the near future, thanks to technical innovations and more sustainable cropping strategies. In this sense, a very minor change in some villages (a technical innovation related to water management, for example) could set the ground for a regional transition, which could have future implications for the quinoa market, and feedback loops again on producer threats or opportunities.

This potential recalls a recent and brilliant paper by Lauer et al., which helps us to challenge the common understanding of resilience as good and vulnerability as bad by stating that communities must inevitably negotiate different trade-offs as they manage resilience. The key step here is to understand such complexity, the uncertain system of evolution, and moving from the mainstream of “resilience building” to emergent “resilience and vulnerability management”.

Quinoa and the butterfly effect: how can a grain from Bolivia influence urban resilience in Barcelona?

Far from its geographical origins, quinoa (synergistically with other exotic organic super healthy products) is contributing, in cities, to a boost in business opportunities and quality of life. Writing this post from Barcelona, a city which is smoothly recovering from years of hard economic crisis, the only sectors which have definitely not shrunk, but have grown in the last few years, are the luxury sector, tourism, second-hand markets, and organic farming. In interviewing local organic farmers, nobody fears the competition of exotic healthy superfoods. On the contrary—they know that the organic market is just 3 percent (2015 data) of the total food market of the region, and almost any (local and exotic) organic product boom can contribute to promoting consumers’ behavioral change towards a more organic, healthy, and sustainability-oriented life style.

When, a few months ago, I was working on a paper assessing all the different facets of Barcelona’s “resiliency” (from the most classic risk reduction-oriented ones, to the urban ecosystem services or social ones), a key insight was realizing that the city’s “generic” and core resilience feature was the Catalan people’s business capacity and ambitions, which are strongly linked to their identity (being Catalan, and proud of their city). When referring to city resilience, we mostly look to the built environment: critical infrastructures, urban services supply (business continuity), and people’s safety from different hazards. However, in time and across city history, the resilience of a city is also based on its capacity to stay alive, and to stay alive means to maintain your economic performance.

From being a small city just a century ago, Barcelona has attracted big events and has invested in its infrastructure, public spaces and, therefore, in its image as a trendy and vibrant Mediterranean city. The success of its urban governance is known to planners as the “Barcelona Model”. Based on effective public-private partnerships (although these are contested by most scholars because of the social bias of this model, which is mainly oriented towards city branding for enhancing city attractiveness and competitiveness), the city reinvented itself many times, pretending (and creating different brands) to be: after the Olympics, Barcelona the Green city, Barcelona the Smart City (thanks to its massive investment in technology and infrastructures) and, currently, Barcelona the Resilient City (since it was recognized by the UNISDR in 2013 as a resilient city role model, and in 2015 by the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities Challenge).

I lived in Barcelona for 6 years before returning to Italy, and in my neighbourhood I was impressed by the speed at which new trends and investments opened new activities and constantly kept change alive. Within the latest smart, green, resilient city moods, and under the current “Barcelona Inspires” city brand—launched from the Municipality to self-promote the creativity and business opportunities of the city—the emerging hipster, organic, handmade, healthy food lifestyle paradigm brought quinoa to me and, to the city, one of the many innovations playing their roles in the urban economy’s resilience. But how is this key economic resilience engine in Barcelona related to quinoa, and other emerging super-grains? How are these related to global commodity chains, and those chains to the mechanisms redistributing worldwide, temporary windows of opportunity, as well as related threats, to remote areas?

I cannot say definitively that a grain of quinoa from Bolivia can influence the success of Barcelona city resilience, but this grain from Bolivia, like teff from Ethiopia, or coconut water from the Philippines, is, indeed, a small player in interlinked global processes, which shape opportunities and innovations, vulnerabilities and resilience, in cities everywhere.

Lorenzo Chelleri

L’Aquila

Further resources

Chelleri, L., Waters, J.J., Olazabal, M. and Minucci, G. (2015). “Resilience trade-offs: addressing multiple scales and temporal aspects of urban resilience.” Environment and Urbanization, 27 (1) pp 181-198

Chelleri, L, Minucci, G. and Skrimizea E. (under review) “On quinoa revolution and vulnerability trade-offs”, Regional Environmental Change

Add a Comment

Join our conversation