I have just returned from an exhilarating week spent in a workshop with a collection of UrBioNet members. UrBioNet is a network of researchers, practitioners, and students with an interest in urban ecology and biodiversity. It is broad in its remit: while it offers opportunities for discussion and sharing, it singles itself out in having a particular interest in forwarding empirical work in the fields of urban ecology and biodiversity via data-sharing, collaboration with a view to data generation, and developing teaching tools and curriculum interests related to urban biodiversity.

The recent meeting bought together a small group with two areas of interest, the first being urban ecologists working in Africa, the U.K., and the United States with social interests, and the second being social scientists working on environmental issues. I say “groups of interest” because these groups speak to two significant gaps in urban ecology: there is a notable paucity of work emerging from Africa, the fastest urbanizing continent on the planet, and while we have a growing amount of work emerging that connects social gradients to urban ecological gradients, the exact social mechanisms behind these patterns have yet to be clearly elucidated.

The workshop, led by Paige Warren, Sarel Cilliers, Mark Goddard, Charlie Nilon, and Myla Aronson, was funded through a U.S. National Science Foundation grant secured by the American partners. They had used this opportunity to seek out a particular community of researchers who could link these two areas of interest. That community proved to be a stimulating combination.

In the week together, we grappled with three key themes. The first was an empirical exercise towards a meta-analysis that tackles the difficult terrain of unpacking the social elements that inform recorded urban biodiversity patterns. While we have patterns connecting social factors to biodiversity and ecological measures, these patterns are not always consistent, and we certainly don’t yet fully understand the mechanisms that drive the patterns. The second was brainstorming how we might improve our network engagements and expand the scope and breadth of the network, in particular to grow the number of African urban ecologists and practitioners.

The third focused on expanding the use of the ‘crosstown walk’ as a teaching tool, and it is this that I really want to report back on. In many respects, the “crosstown walk” speaks to both of the other two themes of the workshop in fun and interesting ways, and I will touch on both of these in relation to our deliberations over the crosstown walk.

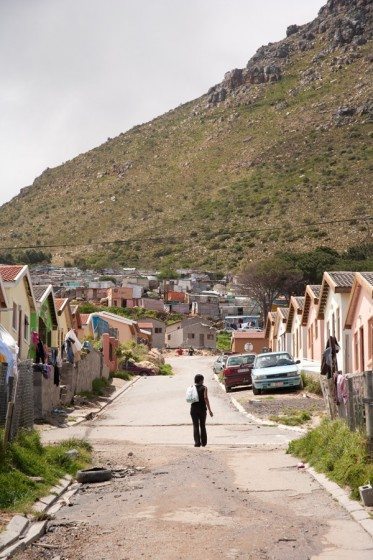

The crosstown walk is the brainchild of Charlie Nilon and George Middendorf, and has been presented in a previous TNOC essay. Essentially, the crosstown walk is an urban ecology teaching tool where ecology students must walk a pre-determined socioeconomic gradient across their home city or town. The purpose of the exercise is two-fold. First, it makes students examine and question the environment they see. The students must determine what they think the dominant social and ecological patterns across the gradient are, or what the more subtle ones are. They are expected to observe, ponder, and hypothesize, all fundamental elements of any scientific endeavor.

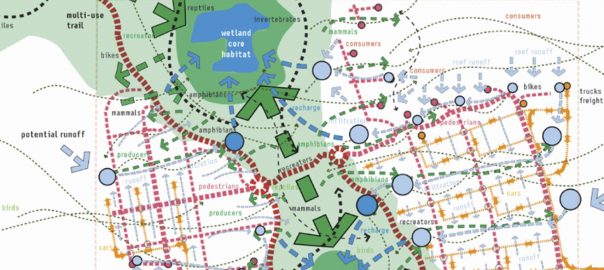

Their second task is to collect data along the gradient to interrogate the relationships they believe they observe. Data gathered can really be anything, and this is the fun part. Students must apply their minds to the question of what readily-observable or collectable measures along a city street can be gathered that will serve to unpack the relationship between social, economic, and cultural aspects and environmental conditions. These could be building disrepair, types of cars parked in front of houses, yard size, the presence of large trees, lichen on trees, weeds in sidewalks, street lighting, birds, potted plants on porches, or anything else the students develop.

The idea is to get the students to interrogate the kinds of measures they intend to capture and why they believe these might relate to each other. In our workshop, as I mentioned, one of our tasks was to grapple with the question of how the metrics used as proxies for socioeconomic status relate to observed patterns of urban biodiversity or other ecological elements. We spent a considerable part of our six days together grappling with the relationships that underpin urban biodiversity and ecological patterns.

This is interesting and valuable terrain, as we do not fully understand the social processes behind biodiversity outcomes and these seem to vary across the globe. While many studies show increased biodiversity with wealth, the actual mechanism behind this pattern has been speculated about, but is not always clearly demonstrated, and some studies show different relationships. Patterns seem to be underpinned by textured and complex factors such as environmental context, tenure, local histories, and cultural dimensions, and these all playing out in concert or in any myriad of combinations. Further, any patterns relating to social-ecological status may well have environmental justice implications, rendering them critical outcomes that should inform city planning.

The fun part here for any student taking a crosstown walk, gathering data towards exploring socioeconomic and nature relationships, is that while we have some inkling that patterns do exist, we have by no means buttoned up this relationship. Also, because data capture and sharing are main features of the UrBioNet group, we can readily attest that there is a chronic shortage of data from cities relating to urban ecological patterns and an array of socioeconomic factors, particularly in the developing regions of the globe. This is certainly true of Africa. Any student participating in a crosstown walk should know they are working in the realm of the un-resolved and potentially contributing data to a “data scarce” space.

Of course, not every crosstown walk is going to generate data of sufficient volume or quality to warrant its inclusion in any substantive study. But what if a number of students, or classes, across the globe were all collecting data and we set our sights on a larger, collective, data-gathering exercise? Now, this links to the second theme in our workshop, that of network expansion, particularly in Africa. I had been planning to get my urban ecology class to do a crosstown walk for a while, and in the workshop, Charlie and I hatched a plan to make this a global teaching exercise: we will get our students to do their crosstown walks at the same time of year and then get them to share experiences and data to allow for an even better learning experience. Students will be able to get a sense of how their own city varies, and then make comparisons to another city elsewhere in the world. We believe this will add significant value to the urban ecology learning experience, and could potentially generate datasets worthy of global comparison and reflection, in addition to growing a cross-cultural learning experience.

Charlie and I got so excited that before the end of the meeting, we had Sarel Cilliers of North-West University in South Africa on board to run a simultaneous crosstown walk with his class, too. We now have three crosstown walks planned for September 2016. The opportunity to compare across the globe will get students scratching their heads over the same sorts of gnarly challenges we were grappling with in comparing socioeconomic measures and ecological patterns emerging from different parts of the world in the peer-reviewed literature. The difference is, they will be operating in real time and will be able to put challenging questions to each other, sharing reflections, data, photographs, and opinions. I imagine, for example, that comparing data from a sprawling city where yard size is comparable across a socioeconomic gradient to one where yard size is significantly different between socioeconomic classes could allow for interesting comparisons and considerations for standard species-area relationships and how these are—or are not—affected by socioeconomic status. How, for example, might data compare across cities of different ages, or ones of varying history, or cities with different access to public open space? All these subtle factors should prove interesting material to ponder and would only be prompted by work in different cities, something that would be logistically impossible in a single university teaching curriculum. Personally, I am extremely excited about this project and look forward to reflecting both on the data that emerges and, more critically, on the learning experiences of the students.

All in all, it was an excellent workshop. Of course, what I have presented here is only a portion of what we deliberated on in our time together, but I think it captures the spirit of the meeting, during which we wrestled with methods and data capture, grew collegiate relationships and friendships, and generated innovative ideas for teaching and expanding our urban ecology networks and databases.

Pippin Anderson

Cape Town

For more information on the crosstown walk, I suggest you read George and Charlie’s paper, which clearly outlines the teaching tool and process.

This UrBioNet workshop was funded through NSF RCN: DEB #1354676/1355151. For more information on UrBioNet, find us on Facebook and on Twitter @urbionet_RCN.

I love this idea!

do you have more details or data to share?

cheers,

chris.