I have written in previous articles (here and here) that Kampala’s urban landscape has been largely fragmented, just like the landscapes of many other cities. In fact, this is the common character of urban development. But it isn’t the only way. In this article, I illustrate the urban risks that Kampala faces—especially those related to natural hazards such as flooding—and demonstrate how diverse forms of nature within Kampala can be harnessed to reduce such risk. This is not based on the dominant grey infrastructure approach (technological-engineering solution) to risk management, but a counter argument: that risk reduction through and by use of nature can be achieved in cities such as Kampala.

With increasing climate variability as well as future projected climate change, the urban risks associated with these changes are likely to increase [1]. The climate-induced risks, coupled with the nature of urban development, accentuate urban risk in Kampala. The nature of topography, ecosystems, and urban development interact to cause frequent flash floods in Kampala that affect housing, infrastructure, and social services. Disruption of transport in the city usually occurs whenever there are heavy downpours in Kampala.

But if nature is systematically and strategically embedded in urban development, we can reduce impacts from a range of urban risks. From mudslides on steep slopes, floods, air quality, and health outcomes of these hazards, nature in Kampala has the potential to reduce the risks.

Hazards, exposure and urban risk in Kampala

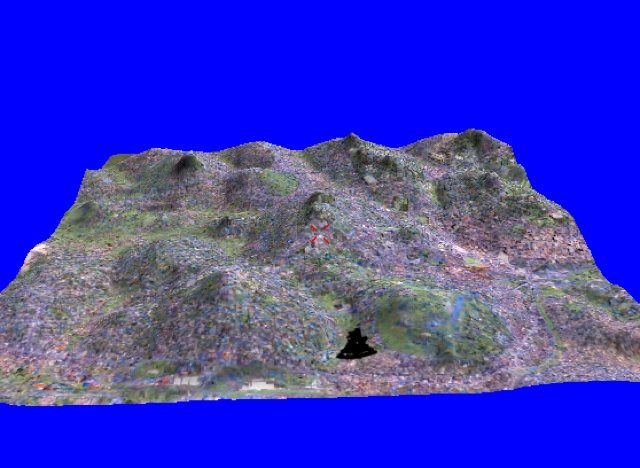

Flooding in Kampala is among the most common and widespread hazards, with impacts on the economy, business, infrastructure, housing, and livelihoods. They can even be life threatening [2]. Kampala experiences flash floods virtually every year, leaving little room for recovery by personal households or by institutions with respect to infrastructure. The topography, comprising hills, wide valleys, landscape changes, and inadequate drainage infrastructure for runoff combines to affect the city from upslope to downstream, as shown in the figure below.

Flood-related losses and damage to people’s property is escalating, while the cost of maintaining roads and drainage channels is also on the rise. One of the key outcomes of flood-related risk is a downturn in public health. The incidence of water borne diseases—such as cholera, typhoid, dysentery, and malaria, which are linked to flood and precipitation events characterized by variable climate—is increasing. Although the flood events occur in low-lying areas often occupied by informal settlements, the wider, knock-on effects on transportation, economy, and infrastructure also influence middle and upper income groups. In this way, the entire city is exposed to these climate-induced risks, despite geographic-, location-, and spatially-differentiated social groups.

The most important infrastructure is located in exposure zones, which are low-lying. Because of this exposure, even a light downpour in the catchment can cause anything from loss and damage to high runoff accumulation.

In addition to floods and related health risks are the less known and less documented risks associated with high temperatures and air pollution. There is a loose connection between high temperatures during the dry seasons with the hottest nights and respiratory diseases, and the same for air pollution, which is also usually at its highest during this period due to a haze that is driven to the region from dry winds that blow over the Sahara desert. The other driver for the haze and dust, which increases PM, is dusty roads; unpaved roads in the city range between 1000 and 1400 km in length.

But it is important to reflect on flood mitigation efforts, most of which are concentrated around Kampala city and are technology-based. The more it floods, the more the city authority designs drainage channels to accommodate the runoff. This technological approach to potential flooding has led to the persistence of urban risk in Kampala. Two of the four major drainage systems have been constructed with concrete lining and more are yet to be expanded under a multi-lateral funded project on infrastructure in the city. The thinking is that the major drainage channel modifications will solve the flooding problem.

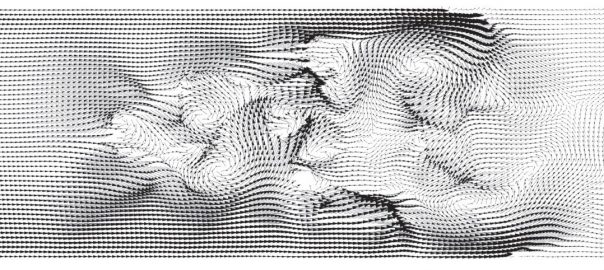

However, there is increasing evidence that the flash flood problem in Kampala is an interaction between upstream and downstream surface conditions. These conditions relate directly to land cover, which is characterized by degrading natural vegetation as it is cleared for housing and infrastructure development. The higher the roof area, the higher the runoff, and when drainage channels are constructed without cascade design, then the time lag for runoff to reach downstream is shorter. Thus, due to limited infiltration, runoff rapidly moves in the form of pipe flow.

As urban growth and development continues in Kampala, there is an increasing surface condition-created discharge of runoff. Changes associated with urban development, such as channel modifications, storm-sewer construction, and paving of pervious areas, can increase flash flood hazards in the city.

Changing landscape and risk in Kampala

In Kampala, the landscape is a combination of structures and green areas. This landscape has been changing with urban developments and will continue to change. The hilltops and upper slopes are losing tree cover, which is important for infiltration and the slowing of surface runoff. The lower slope and valleys are losing vegetation, which otherwise would slow the velocity of streams and aid in retention. Instead, the valleys and lower slopes are increasingly being urbanized, exposing many buildings, infrastructure, livelihoods, and people to flash floods. As mentioned earlier, the Kampala City Council Authority is in the process of embarking on planting trees in Kampala with a high mark. But this greening is selective and, perhaps, not strategic enough in view of reducing flood risk or air pollution. By focusing on beautification and planting of tress along streets, there is a missed opportunity to utilize nature in reducing flood risk: strategically greening hilltops for multiple purposes, including runoff management. We are losing trees at an alarming rate, especially on hilltops and in lowland areas.

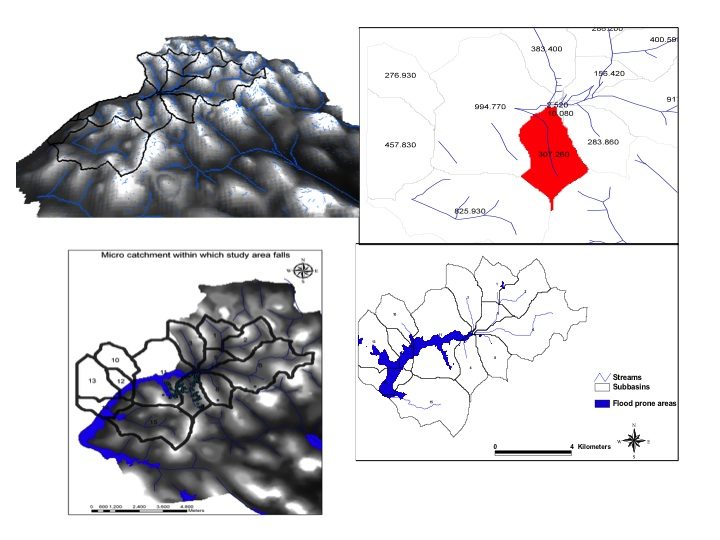

For example, in one of the sub-catchments (as shown in figure 2) of Kampala, the loss of tree cover couples with waste management practices, unplanned construction, construction in wetlands, small size and depth of drainage channels, intensive rainfall, and poor drainage maintenance to cause flash floods, with the most affected areas being those located around wetlands. In this micro-sub catchment, runoff is generated by a fifth of the area, mainly because of the relative steepness of the slopes and connectivity and density of housing units. This runoff is likely to increase as more impervious surfaces are created to match increasing development trends. The effects of urban development on runoff characteristics are widely acknowledged and include decreased low flow and groundwater recharge, increased surface runoff in annual stream flow, increased magnitude of peak runoff, decreased lag time between rainfall and runoff response, increased rate of hydrograph rise and recession, and decreased mean residence time of stream flow. Technological solutions are unlikely to solve the problem because the capacity of the drainages will have to be consistently increased, placing huge costs to the city authority. The current engineering work to increase drainage channel size will not reduce flood risk in Kampala, though upslope management activities can enable more infiltration of rainfall. Still, the loss of vegetation cover reduces the ability of the urban ecosystem to reduce ambient particulate matter, which causes respiratory diseases. This occurs both upslope and in the valleys of Kampala. The loss also has effects on micro-ecosystem service of moderating temperatures, which would otherwise reduce the risk associated with hot nights during the dry period.

How restoring nature reduces urban risk

It is clear that nature is useful and should be part of the range of solutions to reduce risk, whether in relation to floods, air pollution, or moderating heat in urban areas like Kampala. But how, exactly, can nature be harnessed to reduce these risks?

In the process of greening, there are competing issues. At the local scale, nature can help in storm protection, erosion control, flood regulation, and microclimate moderation. For example, shade trees not only beautify roadways, but also provide a buffer against high and low temperature extremes, providing natural microclimate control. Conversely, the removal of trees leads to an increase in soil surface temperature and reduced relative air humidity. Additionally, shade trees can enhance soil quality by producing litter fall and pruning residues, which can offset urban heat island effects by increasing the amount of green space within urban areas and their surrounds. Fruit crops and agroforestry also provide shade, which can reduce land surface temperature and hasten night time cooling [3]. Agricultural lands and urban gardens increase evapotranspiration, thereby lowering temperatures through evaporative cooling. The potential for carbon sequestration by nature has not been adequately analysed, but agroforestry is associated with minimal carbon emissions and the trees absorb carbon.

Other co-benefits of urban forestry include windstorm reduction and, to some extent, maintenance of soil hydrology, which can stabilise slopes and reduce landslides. Hedgerows and shade trees provide buffers against strong wind gusts, reducing the overall intensity of storms and damage to infrastructure. In these ways, urban forestry and agriculture can help mitigate landslide hazards associated with an increased frequency of rainfall events by stabilizing steep slopes where urban expansion and residential development often occur. Urban agriculture has demonstrated flood reduction capabilities in Kampala by extending the lag time between floods and slowing stormwater. Reduction of surface runoff from urban forestry ranges between 15-20 percent of rainfall, depending on surface conditions, soil composition, and permeability. In addition to reducing runoff, more porous land surfaces (such as soil) support recharge of water tables and increase groundwater flows. And wetland ecosystems are recognized as economically sound and effective alternatives to traditional water treatment practices; ecological management of water purification may provide useful strategies in Kampala, where often only a fraction of wastewater is treated [4].

Plot-level to citywide restoration of nature

There is a wide range of nature-based solutions, from the plot level to the city level, that can reduce risk. At the plot level, for example, drainage ponds can capture storm runoff, then release it after the rainfall event to reduce surface runoff and increase lag time for stormwater. Rainwater harvesting at the plot level can be used for different purposes, including productive greening. But preservation of tree cover on hilltops to enable infiltration is important for stabilizing slopes, especially given the mudslides associated with excavations and constructions in the city. On some hills in Kampala, such as Kololo, extensive tree cover reduces slope instability; they have almost no accidents compared to other parts of the city. But the upstream to downstream connection is critical: several interventions, including preservation of retention areas with natural cover upstream and using lowland areas to increase tree cover, could attenuate floods in the city.

Conclusion

Technological solutions are not the panacea for urban risk reduction, especially with regard to flood risk and health outcomes related to floods and air pollution. Nature has an important role to play and, based on some examples of existing slopes with few or no disasters compared to other parts of the city with hills that have experienced disasters, may reduce urban risk to a great extent. Living in harmony with nature in urban Kampala will be possible when strategically targeted greening, which includes planting trees, can increase infiltration, reduce particulate matter and air pollution, and slow runoff. Urban risk in Kampala can greatly be reduced through greening and restoration of nature in lowland forests and hilltop forests. Given that Kampala lies in a tropical zone that receives substantial rainfall, flooding will simply continue if technological solutions are taken as the primary risk reducing measures.

Shuaib Lwasa

Kampala

References

[1] IPCC, Summary for policymakers. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, New York, NY, USA, pp. 1-32., 2014. [2] UN Habitat, Cities and Climate Chage: Global Report on Human Settlements, 2011, Earthscan / UN HABITAT, 2011. [3] S. Lwasa, F. Mugagga, B. Wahab, D. Simon, J. Connors, C. Griffith, Urban and peri-urban agriculture and forestry: transcending poverty alleviation to climate change mitigation and adaptation, Urban Clim. 7 (2014) 92–106. [4] S. Lwasa, M. Dubbeling, URBAN AGRICULTURE AND CLIMATE CHANGE, Cities Agric. Dev. Resilient Urban Food Syst. (2015) 1.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation