about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

What are “landscape initiatives”, and can they transform how we create cities and their surrounding regions?

Key to the relevance and context of this roundtable is the very meaning of the word “landscape”. One dictionary definition reads “all the visible features of an area of countryside or land, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal”. But this definition is not nearly comprehensive. Where it fails is in the limiting effect of the words “visible” and “aesthetic”, because in fact the word landscape conveys a richer meaning that includes, of course, the aesthetics of nature and the out of doors, but also the organization and design or infrastructure, the biophysical and social services of ecosystems, the livability of communities, and the justice aspects of how our living environments are (or are not) democratically decided upon and created.

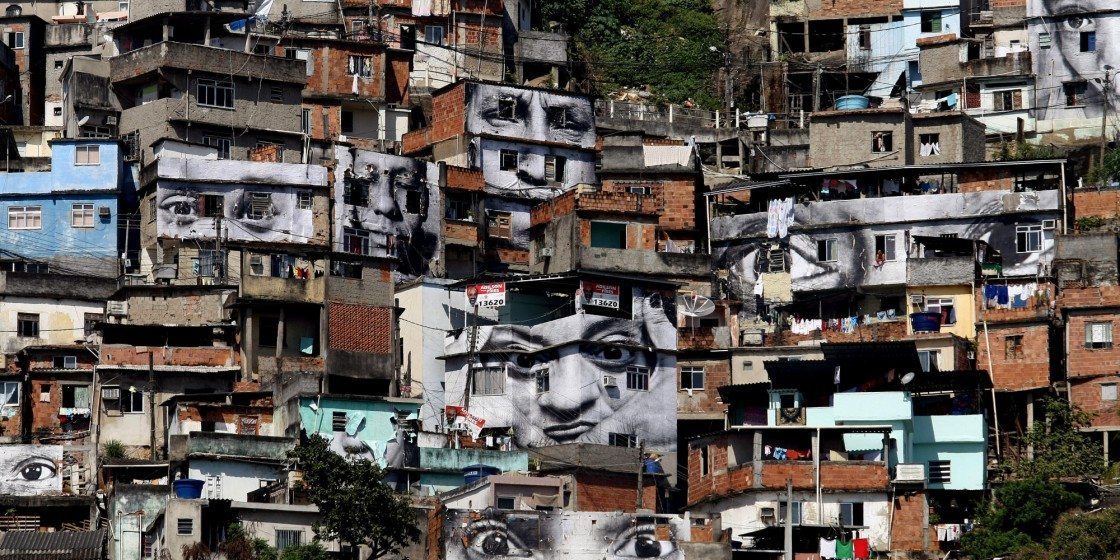

Indeed, in recent decades, the concept of landscape has surpassed its limited traditional meaning, which was intimately bound up in the visual perceptions of open space. Today we speak of landscape as a system of services (e.g., ecosystem services), as an expression of social relations, as balances of designed open space and wild, and as a result of everyday experience—that is, as a superposition of layers of many meanings and values embodied in a particular place, and which is central to a place’s identity. To use a line from The Nature of Cities’ mission statement: “[cities] are ecosystems of people, nature, and infrastructure”. In other words, they are landscape in a complete and integrated sense.

How can we build such an important constellation of concepts into the planning of better cities—cities that work for people, communities, and the environment? Such a challenge requires integration of many streams of thought and action: design, ecology, sociology, psychology, governance, law, justice, inclusivity, and participatory democracy. It’s a tall, but critical order. The so-called Landscape Initiatives are a way forward. The European Landscape Convention, agreed upon in 2000, was the first international treaty to be exclusively devoted to all aspects of landscape, and it is the touchstone for many similar efforts around the world, some of which are described in the following contributions. These global attempts at the broad value and meaning of “landscape” have similarities, but also take locally adapted forms. And they can be central to creating cities with the attributes we crave at The Nature of Cities: resilience, sustainability, livability and justice.

about the writer

Menno Welling

Menno Welling is the owner and lead consultant of African Heritage Ltd in Zomba and African Heritage Consulting in the Netherlands. His interests are in African archaeology, cultural landscapes, heritage tourism and intangible cultural heritage.

Menno Welling

Currently, Zomba is the fourth city in Malawi. But while the other three are ever expanding, Zomba seems to maintain a status quo. There is no big industry, and government departments are slowly moving out. In colonial days, Zomba was the capital of the Nyasaland Protectorate. It was founded by the Blantyre Mission of the Church of Scotland in the 1880s, and British Consul A.J. Hawes decided the little settlement—at the foot of a lush green plateau with several mountain streams—would be the ideal place for setting up central government administration.

In Zomba, Malawi, historic preservation and greenery seem to be considered antithetical to development and the modern city.

In the course of the next decades, Zomba slowly developed. Office buildings were constructed in vernacular architecture and residential areas laid out, the latter following racial and social segregation, as was common in that time. The high ranking white officers lived up the slopes of Zomba Mountain. A large golf course separated them from the African and Asian communities down below. In those days, Zomba was known as the Garden Capital of the British Empire. Indeed, the comparatively moderate climate lent itself to urban greenery. Trees were planted along the roads—and not only in the upper class area. Privately, the British officers, if not their wives and Malawian gardeners, tended their gardens in typical fashion. The common lot size in the white area was 1 hectare, allowing for sizable lawns surrounded by tropical flowers and trees. These, in turn, attracted the most colourful birds, such as Livingstone’s turaco and various hornbills.

After independence, President Kamuzu Banda decided to move the capital of what had become Malawi to Lilongwe, which was much more centrally located. The city of Lilongwe was developed with the aid of South African urban planners in the 1970s. Following South African principles of ‘divide & rule’ the Lilongwe neighbourhoods, or “Areas”, as they are called, were spaced wide apart, separated by bush or agricultural land. Ever since, Zomba has gradually seen its government departments and the parliament move to Lilongwe. Whereas other British colonial capitals in Africa have become metropolitan cities with high-rises and skyscrapers, Zomba has, for the most part, retained its charming colonial character. Indeed, its historical core would be worth a World Heritage nomination. Just as nearby Mozambique Island is an outstanding example of Portuguese colonial heritage. And like Mozambique Island–or Zanzibar, or the Island of Gorée, for that matter—Zomba could exploit that heritage for tourism purposes in order to boost the local economy.

As it is, such developments seem far away. In April 2014, Zomba City Council started cutting the century old Mahogany trees that flanked the main road through Zomba and which are its hallmark. Historical buildings such as the District Assembly and the regional police headquarters were marked for destruction. As any modern city, Zomba was to have a dual carriageway, and greenery and buildings had to give way. From an urban planning point of view, the proposed development was poor; it had all the signs of a political campaign tool of a sitting president seeking re-election who had not yet left a tangible legacy in her home district. City administrators seized the opportunity, as a more sensible city bypass might never come.

On technical grounds, a group of concerned citizens managed to get a court order against further destruction and the National Roads Authority settled for merely redoing the existing road. A lot of damage to the trees was, however, already done. Given vested interests, even some trees outside the construction zone had been cut. Two year later, little seems to have come from the mandatory replanting of 500 trees as part of the court settlement. And another mahogany tree was just cut down by a local resident citing laxity in pruning by city officials.

Yet another development is threatening the garden city of modern Malawi. Under the pretence of security concerns, homeowners have started erecting brick walls around their plots. If this tendency is not kept in check, the pleasant mountain roads along lush gardens and charming white houses will turn into brick funnels. How would this historical neighbourhood then be different from a newly built, middle class area in, let’s say, Lilongwe?

At the heart of these issues lays the concept of development. I dare say security concerns in Zomba do not warrant a brick wall fence. The wall has become part of the middle and upper class homeowner mentality. The same goes for city officials; historic preservation and greenery seem to be considered antithetical to development and the modern city. At the same time, officials may opt for immediate benefits, rather than the elusive prospect of increased tourism potential—despite such being included in the Urban Development Plan.

about the writer

Laura Spinadel

Architect, Urban Designer, Landscaper, Filmmaker, Multimedia Communicator, Editor. Cisiting professor in Spain, Brazil, Mexico, USA, Italy, Colombia and Argentina.

Laura Spinadel

Tell me, when you were a child, were you allowed to play in the street?

I am constantly confronted by PRIVATIZED public space which is marked by Big Brother and the fear of what is different.

Autobiographical details mark us out in our thinking and our actions. I am convinced that the work I do is shaping society…and that often makes me aware that I must constantly feed my curiosity with images and experiences from all over the world. Seeing how different cultures spend their time in society is my definition of URBANITY. And by building living spaces as an integral designer, it is from those gaps that I must permanently tame the INNER CHILD we all have inside of us, in order to be open to other ways of experiencing the multiple realities that exist. My key has always been to link space with TIME, which is what leads us to understand that everything changes, and that what is important is to be sensitive, and to recognize the POTENTIAL that we must awaken in people so that they can relate to it and evolve.

Going back to the question. I was not allowed to play alone in the street because I lived much of my childhood under military dictatorships in Argentina. Nowadays, I live in a city where everyone takes “pride” in not playing in the street because that is what foreign immigrants do. In my work as a holistic architect, I am constantly confronted by PRIVATIZED public space that, obviously, nobody wants to pay for, and which, in our globalized culture, is marked by Big Brother and the fear of what is different.

It was very interesting when, a few years ago, I made a film about Campus WU in Vienna, interviewing all of the protagonists who interacted in the conception and realization of the largest University of Economics and Business in the European Union. I asked all of them the same question to kick off the dialogue. Economists, architects, politicians, etc.—all people from different cultures who, together, helped us create this MIRACLE, each of them complementing the others with their NOSTALGIA, using our vision to give birth to a place for FREEDOM. The miracle was that everyone was ready to synchronize with the vision of creating a huge university park which would be open 24/7 for everyone—overcoming all preconceptions—where overstretched economics students would cross paths with visitors to the popular Prater amusement park; and with hoards of football fans who lay waste to everything before the game, drinking beer on our campus; and with international tourists trying to get a selfie in front of a piece of architecture from the “Star System”.

But…careful…don’t think that we have overcome the 1960s and that everyone respects pedestrians, or that investors have suddenly discovered that they want to be patrons who BRING MORE LAUGHTER into society. When we won the competition for the Masterplan Campus WU, we had no budget for the 70,000m2 university park, nobody in the city had thought about the impact of having 30,000 intruders in a neighbourhood of 100,000 people, and, of course, there was no facility manager to set limits by pointing out that having a university open to society would result in maintenance and security costs that were higher than those for a mega building with an indoor academic life.

I think it’s extremely important that someone moderate the process and set up a Hannah Arendt “table” in order to interrelate interests and allow the process to gestate COMMUNITY. In this case, it was an anthroposophic Latin American woman dreaming of a better world who managed to wake up the perceived enemies—ECONOMISTS—to the belief that public space was the added value, in order to change perspectives so that we could RETHINK ECONOMY.

In the last few years, I have travelled extensively around the world presenting this project, which has not just stayed on paper, but through the efforts of thousands of people has been transformed into a contemporary space that is driving the economy and culture in Vienna. It is not a space which is merely a baroque jewel; it is a PROCESS that this city was encouraged to start. I must say, in answer to your question, that I’m frightened by the housing speculation bubble that is destroying all of the values that I am talking about in terms of building the RES PUBLICA of the XXI century. I am given hope by initiatives such as the Landscape Law in Chile, Flower Power Neighbourhood Movements in Australia, and the new American generations in Washington who do not want the American dream.

We are learning to see and to believe again. It’s worth encouraging creation from within!

about the writer

Steve Brown

Steve Brown is Lecturer in Archaeology (Heritage Studies) at The University of Sydney, Australia.

Steve Brown

Breaking down binaries: landscape and personal heritage

Landscape is not a helpful term when it is used to separate city from country or urban from rural. To confine the term to one or other of these poles is to enact age-old Cartesian binaries in Western thinking. When I think of my home city of Sydney, for example, I recognise that more than 30,000 years of Indigenous occupation has come before me; the suburb in which I live was, until the twentieth century, productive farmland. Thus, in an historical sense, rural landscape (“the bush,” in Australian slang) versus urban landscape is an artificial construct.

Landscape initiatives are most useful when they have relevance to individuals and relate to people’s feelings for places, things, and practices.

I argue that the idea of landscape is useful for recognising and exploring personal or “unofficial” heritage; that is, places, things, and practices valued by individuals, families, and small groups. This is because landscape can be used to refer to the physical environment, processes of change, sensory experience, and perception. To my mind, these different aspects of landscape are most evident in domestic gardens, whether associated with farmyards or suburban backyards. As Australian scholars Lesley Head and Pat Muir show, planting and working in gardens serves to entwine people with local nature-cultures.

I am currently living between homes—moving from a 350m2 suburban property in Sydney to a 56 hectare (140 acre) bush-block near Canberra. Typically, the latter would be characterised as a rural landscape and the former a component of an urban landscape. However, I have always recognised the suburban block as a landscape in and of itself. It was a place where my partner and I created a wonderful garden (and life) with plants for eating and admiring.

An example of the latter is the fiery red peony poppies that we grew in the garden. My partner inherited a container of seeds from his much-loved maternal grandmother, Doris. They grew in profusion in our garden: dense copses of stems up to a metre high with silver-green leaves and topped with spectacular, fire-engine red, pom-pom-like flowers. Year after year, each spring, the self-propagating plants emerge to re-announce their brilliant presence. The poppies mark a celebratory connection with Doris and are a direct connection to a loved family member, provoke sensations of warmth, fun, and happiness. In Sara Ahmed’s words, they are ‘happy objects’.

For me, the poppies are in themselves a landscape, one that entangles past and present, people and place, urban and rural. They are material things imbued with affective power and bound to the physicality of place (our garden). They have a capacity to recall the past (e.g., stories of Doris, sharing seeds with neighbours and friends) and to shape the present (providing a welcoming presence when returning home). Through growing peony poppies and creating a garden, connections are created to people and places—a personal landscape of attachment.

For me, the poppies are in themselves a landscape, one that entangles past and present, people and place, urban and rural. They are material things imbued with affective power and bound to the physicality of place (our garden). They have a capacity to recall the past (e.g., stories of Doris, sharing seeds with neighbours and friends) and to shape the present (providing a welcoming presence when returning home). Through growing peony poppies and creating a garden, connections are created to people and places—a personal landscape of attachment.

So what do poppies have to say about global landscape initiatives and their benefit to cities? For me, landscape initiatives are most useful when they have relevance to individuals and relate to people’s feelings for places, things, and practices. Landscape is neither defined by scale (large or small) nor reliant on binaries such as city/country and material/symbolic. Current initiatives by global NGOs to produce an International Landscape Convention are therefore challenged to find a balance between creating a holistic planning tool and ensuring relevance to people’s everyday lives, whether they are lived in cities or in wide open spaces.

For now, I am off to plant peony poppies in the new garden.

about the writer

Claudia Misteli

Claudia is a social designer, communicator, and journalist who believes that care, creativity, and collaboration are key to building more just, vibrant, and nature-connected places. Born between Colombia’s coffee region and the Swiss Alps, she now lives in Barcelona, blending cultures and perspectives in her work. At The Nature of Cities, she co-leads European projects and TNOC Festival, sparking connections and meaningful action. Claudia also volunteers with the Latin American Landscape Initiative (LALI), helping amplify regional voices and build bridges across Latin America through storytelling, communications, and a deep love for people and place.

Claudia Misteli

A landscape initiative is like living cells. Cells have all the equipment necessary to carry out functions of life. A cell can move, grow, transform, adapt to changes in its environment, and can even replicate itself. A cell has life in itself, but cells have much more power when they group themselves to form something else, something bigger and more complex.

People are the meaning, the instrument, and the main objective of the Latin American Landscape Initiative.

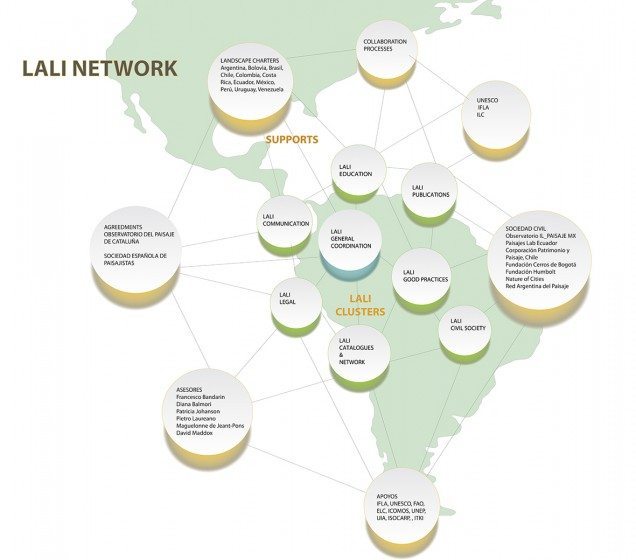

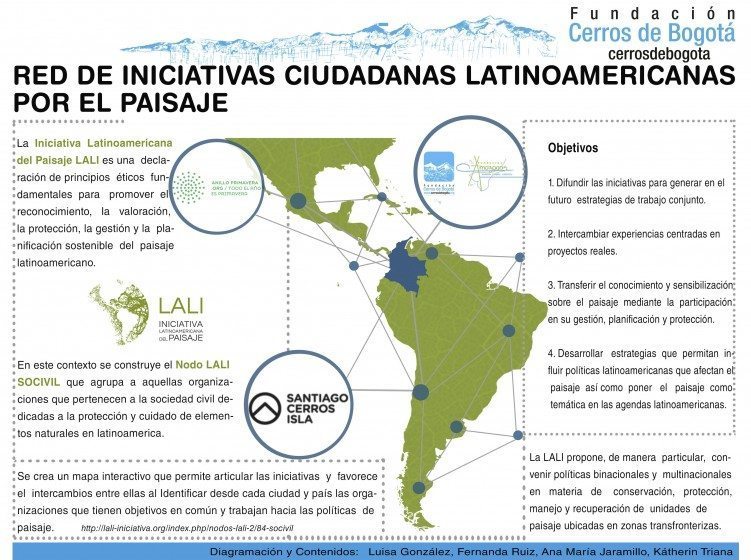

This is precisely the character of the Latin American Landscape Initiative, or LALI, an initiative launched and ratified in Medellín, Colombia, in October 2012. LALI is a living organism that aims to stimulate, at global, regional, and local levels, the recognition and the position of landscape as a fundamental objective in order to protect our past—our heritage—and to configure the future in a more coherent way with nature, people, and their landscape. It’s a bottom-up initiative that, from the knowledge, the experience, the persistence, and the endeavor of people and entities, has been able to weave a large network throughout Latin America for the benefit of the protection, management, planning, and recognition of the landscape.

One of the requirements of an initiative such as this one is leadership. Although these initiatives should be organized in a transverse way without a rigid hierarchy, a leadership or co-leadership of someone, several people, or several organizations, must be present.

A second key factor deals with the idea, the message, that the initiative promotes, as well as its content. For instance, the Latin American Landscape Initiative organized itself in different clusters; although they all deal with different topics and disciplines, all of the clusters are related with each other and need the energy and power of the others in order to go forward. Clusters such as Education, Civil Society, Good Practices, Catalogues, Publications, and Communications are, at present, the core of the initiative.

A third key element, and a very important one when we talk about landscape, is certainly transdisciplinarity. The diversity of approaches and perspectives (from architecture, geography, ecology, arts, publicity, etc.) enriches landscape projects and multiplies all synergies. But it is noteworthy that the LALI initiative could not work without the support and commitment of civil society (in the end, LALI comes from Latin American civil society). People are the meaning, the instrument, and the main objective.

Another relevant aspect, which does not depend on the initiative itself, is the existence of a legal landscape framework that could act as an umbrella for the development of the different activities of the initiative. For example, the lack of this legal landscape framework at a Latin American level has not stopped the work of the LALI—in Europe, the European Landscape Convention already exists—but this legal framework could help strength and provide more tools and possibilities for its implementation.

Cities are, like landscape initiatives, living organisms. This is why cities need these new approaches to develop and evolve, to become urban hubs of ideas, commerce, culture, education, and, of course, to empower people to be more aware of what they have, the cities they want to live in, the quality of cities’ landscapes and the kind of society and values with which they are identified.

about the writer

Kenneth Taylor

Emeritus Professor Ken Taylor has had a research interest in management of heritage places and cultural landscapes since the mid-1980s.

Ken Taylor

My comments focus on the relationship between the landscape idea and cities and the proposition that cities (urban areas) are in fact cultural landscapes (Taylor 2015). The cultural landscape paradigm can be seen to offer a trajectory of thinking relevant to the historic urban environment, not least because we are dealing primarily with vernacular culture, where landscape study is a form of social history. Such discourse in turn supports the notion that views landscape as a cultural construct reflecting human values.

Landscape is not static; it reflects changing human ideologies over time.

The significance of the cultural landscape concept in the urban sphere is that it allows us to see and understand the approach to urban conservation that concentrates on individual buildings as “devoid of the socio-spatial context” that “contributes to a deterioration of the [wider] urban physical fabric” (Punekar, 2006, p.110). Notable to this line of thinking is the emergence of the Historic Urban Landscape paradigm and its evolving pivotal role in the discourse on historic urban conservation. Inherent in this mode of thinking is the role of landscape change that takes place over time with changing values in culturally diverse communities. Landscape is not static; it reflects changing human ideologies over time. In the urban landscape it is critical that we are able to manage change so that historic cities, as they change in response to changing values, reflect their human history, but do not become merely designated historic zones with a tight boundary around them, devoid of a sense of lived-in places. This thinking is summarised by van Oers (2010, p.14):

“Historic Urban Landscape is a mindset, an understanding of the city, or parts of the city, as an outcome of natural, cultural and socio-economic processes that construct it spatially, temporally, and experientially. It is as much about buildings and spaces, as about rituals and values that people bring into the city. This concept encompasses layers of symbolic significance, intangible heritage, perception of values, and interconnections between the composite elements of the historic urban landscape, as well as local knowledge including building practices and management of natural resources. Its usefulness resides in the notion that it incorporates a capacity for change.”

References

Taylor K, (2015), ‘Cities as Cultural Landscapes’ in Bandarin F & Van Oers R, eds (2015), Reconnecting the City.The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage, Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Punekar A (2006), ‘Value-led Heritage and Sustainable Development: The Case of Bijapur, India’ in Roger Zetter and Georgina Watson (eds) Designing Sustainable Cities in the Developing World, Aldershot UK & Burlington VT: Ashgate.

van Oers R, (2010), ‘Managing cities and the historic urban landscape initiative – an Introduction’ 7-17 in Van Oers, R. & Haraguchi, S., eds. UNESCO World Heritage Papers27 Managing Historic Cities; Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

about the writer

Monica Luengo

Monica Luengo is an art historian and landscape architect. Honorary member of the International Scientific Committee of Cultural Landscapes, consultant, and lecturer on cultural landscapes.

Monica Luengo

Cities as landscapes

When I have been asked to participate in conferences on urban landscapes, I have often realized that the organizers intended me to speak only of parks and gardens—of “green” in the city, literally. Therefore, perhaps the first clarification we should make is this: What do we mean by urban landscape?

A landscape approach will be the basis for improving both cities and the global environment.

In recent decades, the concept of landscape has surpassed its traditional meaning, which was limited to the view of a natural landscape that becomes a mental construction in the mind of the observer, which subsequently becomes a critical perception of the territory (European Landscape Convention, 2000). And still further, today we speak of landscape as a system of services (e.g., ecosystem services), as an expression of social relations, and as a result of everyday experiences—as a superposition of layers of different meanings embodied in a particular place, which acquires a particular identity. Thus, a city, or its urban landscape, is made up of an amalgam of territorial, political, cultural, social, economic, and environmental layers.

From this complex view of the landscape—particularly the urban landscape—and because of progressive environmental (and landscape) degradation due to multiple factors, there have been many new initiatives exploring how landscape directly affects the welfare of people and their sense of identity.

These initiatives are born at multiple levels—international, national, regional, or local—since landscape is affected by both global (climate change, migration) and local factors; they are dependent on specific territorial policies. In 2000, the need to address these different spatial scales inspired the European Landscape Convention, or ELC, which includes both the countryside and urban areas. The Convention aims to contribute “to the welfare of human beings and the consolidation of European identity”, and has become an important element in the quality of life of populations. The ELC intends to promote the protection, management, and planning of landscapes, and organizes European cooperation based on the understanding that the landscape knows no borders.

Following from and rooted in the Convention, numerous strategies, national plans, and landscape laws have been established in most of the countries represented in the Council of Europe, and cities have established their own Landscape Plans.

The ELC has had a large influence since 2000. Although it is not compulsory for cities to create a landscape plan, the strength of the ELC has inspired many cities to reconsider the urban landscape with new legislation, rules, or guidelines. Such legal and regulatory work has made cities healthier, safer, and happier places to be. Various actions have been implemented: reducing risk of flooding, planning inspiring environments throughout the urban fabric, taking measures against climate change, enacting biodiversity plans, and even plans that combine all of the aforementioned. This is the case with my own city, Madrid, which a few years ago adopted a landscape plan. Unfortunately, there remain many examples, as is the case with Madrid, in which the “landscape” plan is limited to mostly architectural or aesthetic aspects of the city, largely ignoring people and the complex strata of lived experience in the city. Our collective concept of the “urban landscape” is evolving, but still has some way to go to achieve a consistently holistic view of the urban environment as a matrix of people, built form, and nature.

After UNESCO adopted the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape in 2011, we have seen the great challenge of the conservation of historic cities and their identity for years to come. In brief, the policy suggests abandoning a purely architectural or monumental view of the city, replacing it with a landscape approach. The idea for a possible Global Landscape Convention, another UNESCO project born at this time, has also experienced many impediments to progress. On the other hand, the innovative Latin American Landscape Initiative and MED-O-MED, or MedScapes—referring to the Mediterranean—has found surprising success.

Traditionally the domain of architects and urban planners, the city is still an uncharted area in which to experiment with these new ideas of landscape—ideas that promote an understanding of the urban phenomenon from a holistic point of view. The landscape idea views cities as processes, as dynamic entities in which both the natural and the built play important roles, but many other factors, including people and communities, also have vital influences. Moreover, in today’s world, we must not forget that cities are extraordinary meeting places, places of coexistence and of exchange of values in incredible settings of cultural diversity. Today, during an age of significant migration to cities and among countries, the evolution of cities continues or even is accelerated.

The urban landscape of our cities is changing and transforming at a breakneck speed, and, at the same time, we are faced with severe environmental degradation. Undoubtedly, a landscape approach, in which dynamism is one of the key and appreciated characteristics, will be the basis for improving both cities and the global environment.

about the writer

Osvaldo Moreno

Osvaldo Moreno Flores is a PhD candidate and has his MSc. in Landscape, Environment and City. He has worked as a professor and consultant in landscape architecture and in urban environmental planning.

Osvaldo Moreno

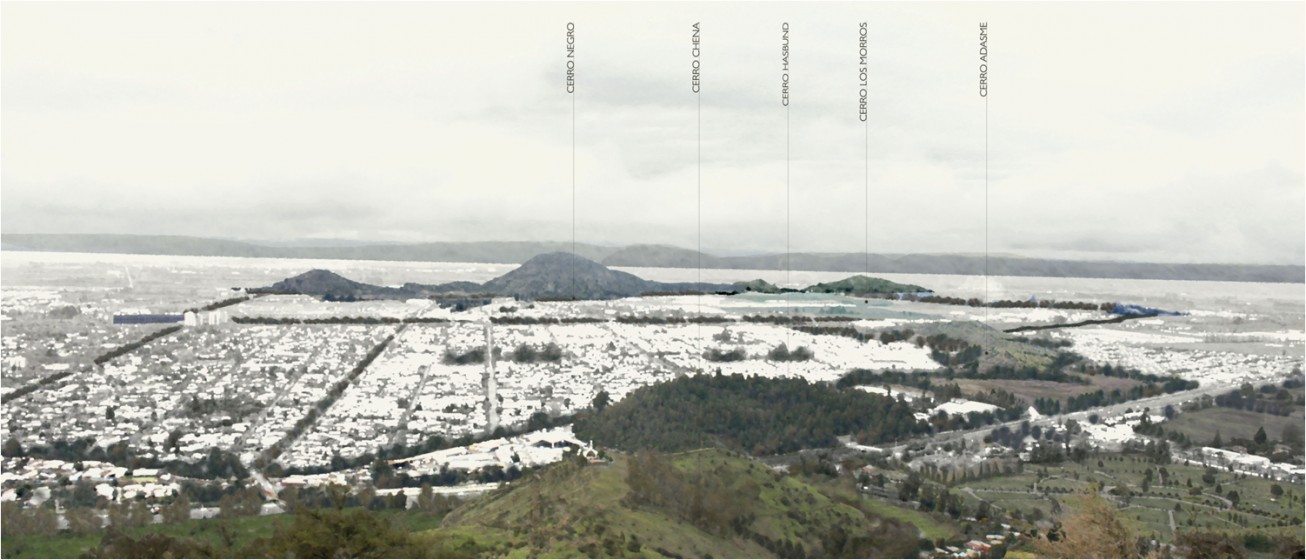

Traditionally, the focus on green areas and public spaces in cities has been characterized by a fragmented way of addressing the problems of planning, design and management, without a systemic approach that can integrate their interrelationships and potential synergies. This has resulted in enabling spaces and equipment in contexts of urban centrality, with high construction and maintenance costs and low impacts on beneficiaries’ coverage. It should be noted here that most Chilean cities are under the standards of green areas per inhabitant defined by the World Health Organization, which recommends 9m2. of green area per inhabitant. In general, cities in Chile have rates around 4m2. of green area per inhabitant (Urban Observatory, MINVU). Under these terms, achieving the standards that relate to improved urban environmental quality is a difficult task, especially if the focus is on building new green areas.

Green spaces’ comprehensive, dynamic, and participatory management represents one of the most important challenges of urban and environmental agendas in Chilean cities.

Moreover, a large number of public and private green areas are located in areas of middle and upper socioeconomic strata, as opposed to the deficit situation observed in low socioeconomic sectors. Such sociospatial segregation affects the provision and accessibility of ecosystem services that green areas provide to city’s inhabitants. Green spaces and their components—at the level of vegetation, soil, water, programs, infrastructure and equipment—are systems that contain important ecological, sociocultural, and economic functions. Therefore, green spaces’ comprehensive, dynamic, and participatory management represents one of the most important challenges of urban and environmental agendas in Chilean cities.

From this scenario emerges the need to incorporate the notion of green infrastructure into public policies that aim to form a systemic and integrated look that can go beyond traditional management models of urban green areas. These policies should promote an innovative approach for rethinking, understanding, and managing those systems and components that contribute to the balance of life in its many forms—human, animal, plant—which generally are degraded, neglected, or hidden in urban contexts. Rivers, streams, creeks, wetlands, hills, farmland, forests, grasslands, parks, and peri-urban spaces—these systems and components, almost in the manner of a puzzle, are available to regroup and to strengthen, to establish synergies and complementarities that benefit not only natural ecosystems, but that also provide strategic functions and services for the population living in the city and its surroundings.

Green infrastructure is defined as an interconnected network of urban, peri-urban, rural, and wild green areas that preserve and furnish ecosystem functions and environmental services for the human population, such as providing clean water, improving air quality, mitigating urban heat island, conserving biodiversity and wildlife, enabling recreation, providing scenic beauty, and facilitating disaster protection, among other benefits. In terms of international experience, green infrastructure as a normative or indicative planning instrument is evident in various initiatives globally, especially in Europe, Asia, and the United States. Among others, the Green Infrastructure and Landscape Plan of Valencia (2011), the Green Belt Plan of Vitoria-Gasteiz (2010), the System of Coastal Forests of Japan managed through programs such as the Forest Conservation Projects (Ohta, 2012), the Natural England Green Infrastructure Guidance (2009) or the Green Infrastructure and Low Impact Development Evaluation and Implementation Plan of the State of New York (NYSDEC, 2012).

Through a green Infrastructure planning approach, our cities can be more sustainable and resilient living systems, improving the quality of people’s lives and helping to conserve ecosystems and landscapes, which are understood as key pieces for the balance of our social, economic, and environmental dynamics.

about the writer

Liana Jansen

Liana Jansen is a registered professional Landscape Architect and an accredited Professional Heritage Practitioner with 15 years experience in the design, planning, and conservation of landscapes.

Liana Jansen

There are a number of landscape initiatives in operation in Africa. The authors of a study published by the GlobalCanopy (2015), identified 73 such initiatives in 32 African countries, most of which have begun in the past six years. Most initiatives were motivated by and have invested in agricultural production, ecosystem conservation, human livelihoods, and institutional strengthening.

We must strengthen professional networks and host planning and events in Africa itself.

One of the largest and most recent is The African Union New Partnership for Africa’s Development, or NEPAD, which launched the African Resilient Landscapes Initiative, or ARLI. This initiative will be implemented through forest and ecosystem restoration, biodiversity conservation, climate smart agriculture, and rangeland management. ARLI will capitalise on previous experience from Africa-led partnerships such as TerrAfrica and work through various existing platforms. The initiative will be implemented through the African Landscapes Action Plan, prepared by African Union NEPAD and partners from the Landscapes for People, Food and Nature Initiative to advance landscape governance, research, and finance through priority actions that embrace all land actors and all sectors (NEPAD 2015).

In a study done by the World Agroforestry Foundation, Hart and colleagues found that integrated landscape initiatives in Africa are investing heavily in institutional planning and coordination, but they have had mixed results engaging different stakeholder groups, especially the private sector (Hart et al 2015). The authors of the Global Canopy study offer many recommendations, but the most applicable in my opinion are the following (GlobalCanopy 2015):

- “Adopt integrated landscape management as a key means to make progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals at national and sub-national scales. Governments, investors, businesses, and communities adopt integrated landscape management approaches within their policies and plans, implementation strategies and reporting processes.

- Empower local stakeholders to design sustainable landscape solutions that meet their unique priorities and contexts. Recognise and strengthen local organisations and institutional platforms for meeting, sharing, consulting, acting, and monitoring in landscapes.

- Build capacity and facilitate learning among key stakeholders for better outcomes in integrated landscape management. Develop learning systems for emerging leaders in integrated landscape management to actively share and discuss lessons from successes and failures. Establish multi-objective landscape monitoring and data systems for adaptive management. Convene multi-stakeholder dialogues to deepen understanding of landscape management and encourage cross-stakeholder communication. Build long-term interdisciplinary research partnerships between universities and landscape initiatives.”

The biggest challenge we face in Africa is often not the amount of organisations operating on international funding, but capacitating existing professionals and academics in countries such as South Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, Botswana, etc. The professionals working in the development sector—architects, engineers, and landscape architects—are actively working on projects not only in their own countries, but also in wider Africa. In my experience, they most often work in silos, not being aware of other professionals operating in the same geographic area and most certainly not aware of organisations involved with landscape initiatives. We must strengthen professional networks and move away from decentralised events and planning in Europe, England, or America, and hosting such events in Africa itself.

Sources

Global Canopy (2015) The Little Sustainable Landscapes Book. Report, available online: http://globalcanopy.org/sites/default/files/documents/resources/GCP_Little_Sustainable_LB_DEC15.pdf

NEPAD. 2015. NEPAD Launches Initiative for the Resilience and Restoration of African Landscapes, available online here.

Hart, AK, Milder, JC, Estrada-Carmona, N, DeClerck, FAJ, Harvey, CA and Dobie, P. 2015. Integrated landscape initiatives in practice: assessing experiences from 191 landscapes in Africa and Latin America, World Agroforestry. 2015 Climate-Smart Landscapes: Multifunctionality in Practice, Published Report.

about the writer

Carla Gonçalves

Carla Gonçalves is a Portuguese landscape architect, researching and advocating for landscape governance. She currently serves as the executive director of the Climate Centre in Póvoa de Varzim.

Carla Gonçalves

The European Landscape Convention (CoE, 2000) has reinforced the role of democracy in relation to landscape, increasing the knowledge and awareness that common people have about their right to landscape and to be a part of the decision making process. Being that landscape is “an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors” (CoE, 2000), what fascinates me is that we cannot rethink landscape without acknowledging the experience of landscape initiatives that are not only designed by landscape architects, geographers, and urban planners, but also by the common citizen.

I believe we need to create a global partnership platform—a World Landscape Campaign similar to the “World Urban Campaign” from UN-Habitat—that helps to share and spread ideas and dialog about landscape.

Cities are witnessing rapid and dramatic changes. New urban territories are not only short of public spaces in terms of quantity, but also in terms of quality. Across the globe, we can find a variety of landscape initiatives in which people are engaging both with themselves and with their communities to protect or improve the common good—the landscape—and, as a result, improving the quality of their lives and of their neighborhoods, enhancing the cities they live in.

If we look carefully, we see that citizens are conscientious of the importance of landscape and that their everyday landscapes are a part of their identities. As a result, people are becoming “landscape changers”, trying to improve the urban environmental they live in, presenting solutions to challenges that today’s cities are dealing with. Landscape initiatives are crucial because they strengthen citizens’ awareness for landscape.

I think that most of the landscape initiatives that we can find today—not only those working at the city scale—are an active response to urgent needs and demands by citizens, in which it’s crucial to engage the stakeholders that have the duty to protect, manage, and plan our landscape. In my opinion, for landscape initiatives to succeed, it’s fundamental to link them to other stakeholders, cooperating towards a shared vision and strategy for our future landscape (regardless of whether we are talking about the national, regional, or urban scale), driven by a participation and proactive process. Bottom-up processes will be the key to transforming our cities—of course, there are many challenges in implementing a collaborative process and there are also many difficulties in defining operational mechanisms to implement it.

The most important thing to keep in mind is that nowadays, these process have already started and progressively more citizens are engaging with landscape initiatives, aiming to reflect on their past, present and future.

I would like to thank TNOC for the opportunity to take part in this roundtable and to discuss these issues, and I cannot finish without throwing a challenge that I think could be very useful to all landscape initiatives around the world.

I believe we need to create a global partnership platform—a World Landscape Campaign similar to the “World Urban Campaign” from UN-Habitat—that helps to share and spread individual, corporate, and public initiatives that protect, manage, and plan landscapes by promoting dialogue, difficulties, and knowledge about our future landscape. Any volunteers?

References

Council of Europe. 2000. European Landscape Convention. Available at: http://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/0900001680080621

about the writer

Martha Fajardo

Martha Cecilia Fajardo, CEO of Grupo Verde, and her partner and husband Noboru Kawashima, have planned, designed and implemented sound and innovative landscape architecture and city planning projects that enhance the relationship between people, the landscape, and the environment.

Martha Fajardo

It is clear that we stand at a critical moment in Earth’s history: we must choose our future. We are living in a time of intense change in the way we value our lives. There is an amazing revival taking place as society, governments, and stakeholders begin to appreciate the true value of the LANDSCAPE.

That landscape represents a direct experience of the everyday life of people explains the growing global interest in landscape.

The adoption of the European Landscape Convention (our inspiration), the UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, the proposal for an IFLA International Landscape Convention, the Landscape Declaration of Florence 2012, the Latin American Landscape Initiative (LALI), the Canadian Landscape Charter, and the Asia Pacific Region Landscape Charter have established the role of landscape as a vital component of collective well-being and have highlighted the need for landscape management at all scales, throughout the region, including the urban and the suburban, cities and towns (especially degraded everyday life), and places with high value for heritage and natural significance.

The rise of potentially devastating problems, such as climate change, ill-conceived urbanization, water shortages, and biodiversity loss means that transboundary cooperation in landscape has become imperative. Nowhere is such cooperation more important than in Latin America.

Today, Latin American society is fully aware that the pressures are a threat to numerous resources, both natural and cultural, and that among them is the landscape. Therefore, we felt that we needed to move forward to stimulate regional and local initiatives through a resolution establishing the landscape as a holistic tool for the planning, management, and creation of sustainable development; in protecting the past but shaping the future, we must recognize the vital connections between government, people, culture, heritage, health, and economy.

Latin American landscape and habitat professionals, together with the academic sector and civil society, initiated the Latin American Landscape Initiative. LALI aims to foster the recognition, valuation, protection, management, and sustainable planning of Latin American landscapes. The initiative acknowledges landscapes as essential components of people’s environment, as an expression of the diversity of our shared cultural and natural heritage, and as a foundation of our identity; it acknowledges the special capacities, responsibilities, and leadership possessed by civil society when intervening in landscapes; and it commits to supporting the elaboration, execution, promotion, and communication of the Declaration Action Plan through the LALI Clusters, Landscape Charters, and members.

That landscape represents a direct experience of the everyday life of people does a great deal to explain the growing interest of the local world in the landscape. It is time to re-focus on local solutions and innovations. The local realm is increasingly viewing the landscape as an engine for its development and a way to boost the level of citizens’ self-esteem, identity, and quality of life. Cities around the world are already acknowledging the value of landscape for urban life; they have shown that investing in landscape and green areas can enhance economic prosperity, health, and social well-being.

From the European Landscape Convention, we have being inspired to see that physical improvement cannot stand alone. Many people care passionately about their landscapes and take pride in their distinctive character and diversity.

“Cities, towns, villages and the landscape are a reflection of their social, political, economic and environmental context. Consequently, any improvement should be part of the well-being of the people. Cities, towns and villages must make efficient and sustainable use of land and other resources; be safe and accessible by foot, bicycle, car and public transport; have clearly defined boundaries at all stages of development; have mixed uses and social diversity; have streets and parks, spaces that respects local history, the landscape and geography; and have a variety that allows for the evolution of society, function and design”.

This is the vision that we link with the European Landscape Convention.

Then, and only then, will the pride we feel as landscape professionals be matched by the quality of our contributions to this world.

Links

LALI Website: www.lali-iniciativa.org

LALI BLOG: www.lali-iniciativa.com

LALI Cluster SOCIVIL: https://www.facebook.com/laliniciativa?ref=hl

IFLA ILC http://iflaonline.org/projects/ilc/

Leave a Reply