Cities pledge to reduce emissions and fight climate change—but do these commitments measure up? The transport sector makes up nearly one-third of urban emissions, a factor influenced by distances traveled and modes of travel. Most cities focus on policies to reduce emissions from modes of travel, such as encouraging residents to switch from personal automobiles to public transport. Land use policies need to be integrated with transportation measures in order to reduce transport-related emissions.

Cities on the frontline of climate action

Many cities have taken steps to address climate change by creating and implementing ‘Climate Action Plans.’ These plans detail current carbon emissions, set emissions reductions targets, and outline strategies to reduce these emissions. City climate plans are not inconsequential—54 percent of the global population lives in urban areas and 70 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions are from cities.

The leadership and initiative of international and U.S. cities were highlighted throughout the UN climate conference, COP21. Over 700 global mayors gathered in Paris at the Climate Summit for Local Leaders, which took place parallel to the official UN negotiations. Global leaders at the Summit, including Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg and actor Leonardo DiCaprio, espoused the importance of cities in driving and advancing measures to reduce climate change. Their message was loud and clear: cities cannot wait for mandates from state or federal governments and must instead be trailblazers to move the climate agenda forward.

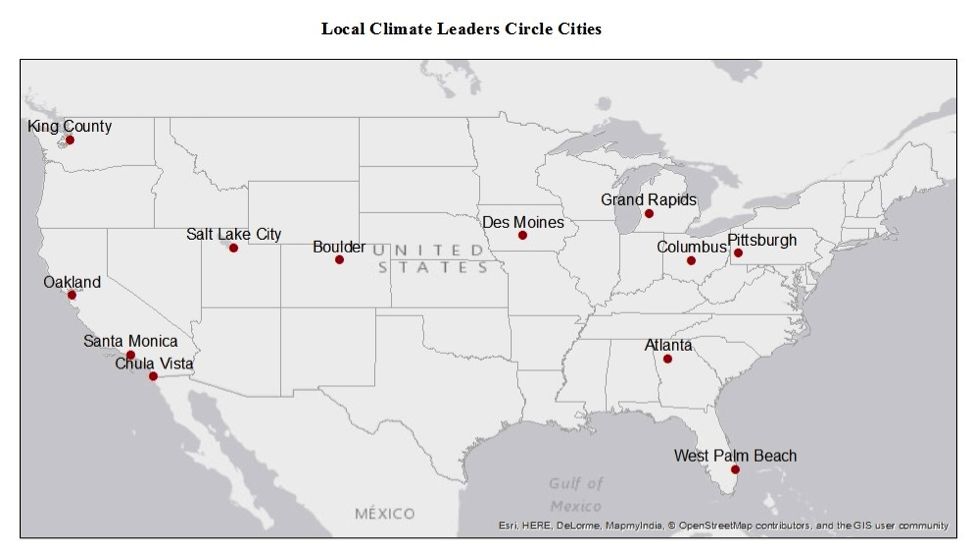

The emphasis on cities was a break from previous climate conferences, and reflected the global recognition that city actions to address climate change are instrumental—but insufficient—for meeting international climate goals . International city networks, including groups like ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability and C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, play an important role in championing and building capacity for cities to action on climate.. A subset of this group present in Paris was the Local Climate Leaders Circle, a delegation of 12 U.S. cities representing the diversity of urban areas in the U.S., from Des Moines, Iowa to Santa Monica, California (see map below for complete city list). These cities were identified as “speaking out as champions for climate action in national and international policy forums” and are the focus of my research on transport-related climate strategies.

Cities pledge to reduce carbon pollution

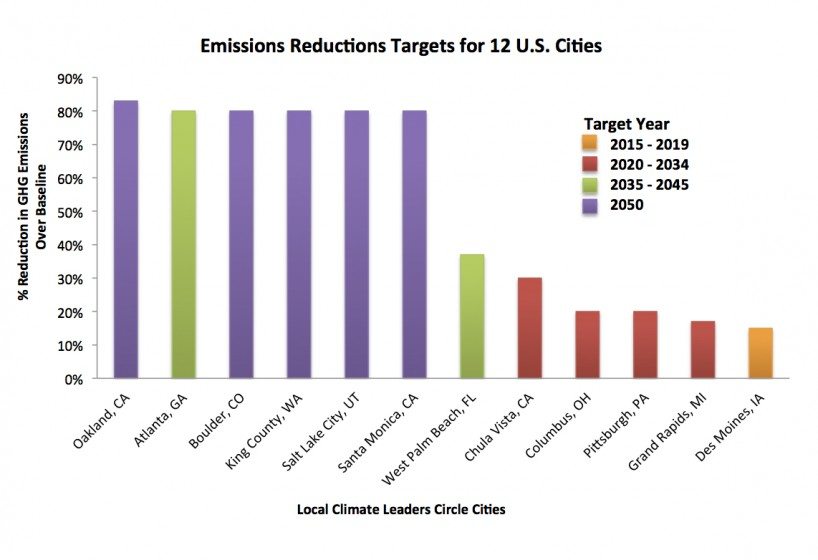

Over one hundred U.S. cities have committed to addressing carbon pollution. Their reduction pledges represent the equivalent of taking 62 million cars off the road, equivalent to a quarter of the 253 million cars on the road today. Cities typically commit to climate change mitigation in order to meet a state directive, or to respond to local leadership or community action. The projected emissions reductions are driven primarily by cities with long-term targets (i.e., 2035-2050). In the U.S., 62 cities have set targets to meet the federal goal of 26-27 percent reduction in emissions below 2005 levels by 2025, and 33 local governments have targets to reduce emissions by 80 percent. Figure 1 below shows how targets and timelines in the Local Climate Leaders Circle compare; nearly half of these cities meet the federal emissions reductions goal.

Setting specific and measurable targets is the first step in mitigating climate change. The next and critical part is figuring out how to reach mitigation goals and establishing indicators to track progress. Cities have a suite of tools available to mitigate emissions associated with urban form, which includes transportation planning, zoning, and behavioral-based policies. Geographic and municipal boundaries impact the policy options available to mitigate emissions resulting from each of these drivers. Even though mitigating emissions from transportation and land use could be an important aspect of city climate plans, few cities adequately create and implement measures to reduce these emissions.

Tackling transportation emissions

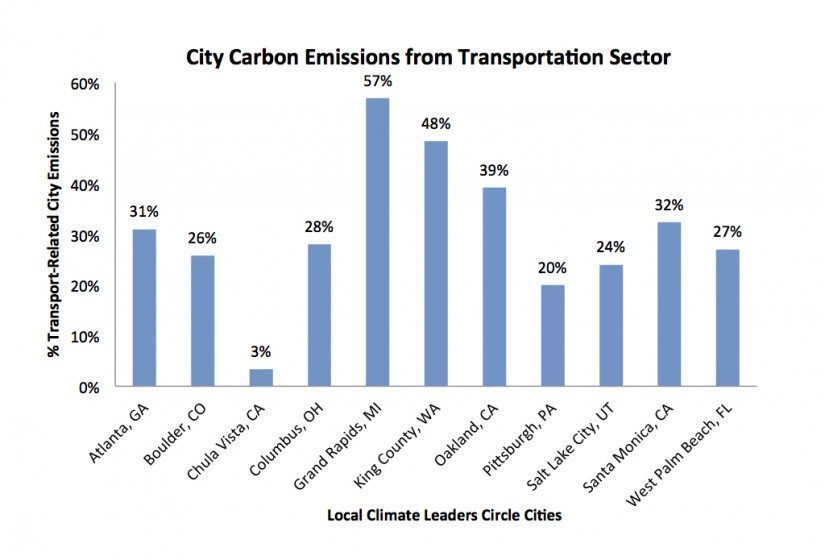

Transportation and land use—how we move around and build our cities—are two of the largest sources of city emissions. Nationally, nearly one third of carbon emissions are from transportation, but there is much more heterogeneity at the local level. Transport-related emissions can vary from 5 percent (Chula Vista, California) to over 50 percent (Grand Rapids, Michigan) of a city’s total emissions (see Figure 2). The presence of a metro or subway system, commuting distances, connectivity of transit options, and spatial composition of housing and jobs has profound impacts on city transportation emissions.

Through climate policies, cities can encourage residents to swap their cars for public transportation, make it easier to live closer to work, or support more efficient fuels. For example, a bike sharing program and electric vehicle charging stations in Columbus, OH, helped reduce the city’s emissions by 3 percent—the equivalent of taking 19,000 cars off the road. Investments made today in transportation infrastructure, housing stock, or other mobility options have long-term consequences for future emissions. If a city invests in low-carbon transportation infrastructure, it will be locked in to a low carbon emissions scenario that will make it easier to meet climate targets.

Cities tackle transportation and land use in climate plans by proposing to reduce emissions associated with vehicle transportation in two broad categories: 1) reduce vehicle miles traveled by promoting alternative transportation options or promote no- or low-carbon fuel sources; or 2) reduce the physical distance driven through land use policies. Mitigation measures in climate plans typically focus on the former category to reduce the carbon intensity of vehicle use, such as encouraging the use of electric vehicles or creating bike lanes. The two most common interventions proposed by cities in the Local Climate Leaders Circle are transportation policies to improve biking and walking infrastructure. Eight out of twelve cities implemented these policies to try and get people out of their cars and using alternative transportation.

Five of the cities analyzed integrated at least one land use policy within their climate plan. A standout example is Oakland’s Energy and Climate Change Action Plan, which begins to integrate land use consideration by reducing vehicle emissions and the physical distance driven. The integration of transportation policies and land use planning is designed to encourage more people to live closer to work and to use safe and efficient transportation alternatives. Oakland uses transport-oriented development to encourage housing development near transportation nodes and along high-use corridors. Street design optimizes bike, walk, and bus rapid transit infrastructure. Regional transportation planning incorporates the needs of Bay Area residents and plans growth targeted to promote sustainable development.

Do the numbers add up?

Some cities are getting it right. After Oakland’s Energy and Climate Change Action Plan was implemented in 2012, the city’s transportation emissions decreased slightly. Other cities that integrated transportation and land use planning in their climate plans, including Atlanta, Georgia and Columbus, Ohio, also reduced their transportation emissions.

Other cities are not doing as well. Transport-related emissions increased by around 18 percent in Boulder, Colorado and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania after they implemented their climate plans. These cities did not integrate transportation and land use, and instead implemented measures to reduce emissions solely associated with vehicle transportation. Boulder and Pittsburgh adopted policies to support hybrid vehicles, alternative fuel use, and an increase in bike lanes and associated infrastructure. But these measures alone are not enough to shift the city toward a low-carbon transportation pathway because of the exclusion of land use measures.

In developed or mature cities, infrastructure lock-in, including transport systems and land use patterns, directly impacts emissions trajectories. Due to the inertia of the existing built environment, it is more difficult to change residential patterns to aggregate housing near transit nodes or along multimodal corridors. The suburban sprawl that characterizes much of American cities and subsequent car dependency will require large shifts in the built environment and the way citizens think about their transportation options. Government policies to bring about these shifts are challenging because the policy options are decentralized, often logistically difficult, and are often reliant on personal behavioral shifts.

In creating climate plans, cities identify emissions reductions targets and measures to achieve those targets. These targets are often not associated with a specific performance level or directly tied to a policy measure. The Des Moines Tomorrow Plan identifies a goal to “provide multimodal access in the region” but it is unclear how the city aims to achieve this goal. Multimodal transportation, which integrates a variety of transportation options (e.g., bus, train, bicycling) into a transportation network, is vague—what type of multimodal access is proposed? How will this be measured? What defines the region and where investment in multimodal access will be centered? Greater clarification and specificity is needed.

Other plans, such as Santa Monica’s 15×15 Climate Plan, are more clear and direct—Santa Monica has a target to increase ridership on the Big Blue Bus by an additional 200,000 annual passengers, which is both measurable and quantifiable. Creating policy measures that are both actionable and quantifiable is tied to better success in achieving emissions reduction targets.

How can cities improve their plans?

Although many cities have reduced overall emissions as compared with baseline levels, the transport-related emissions are increasing in several cities where integration of land use and transportation measures have not been included. As cities develop Climate Action Plans, how can these plans be strengthened to ensure that transport-related emissions are effectively mitigated?

Track progress to meet goals. Not enough data is provided by cities to evaluate which land use and transportation measures have been implemented and whether they have yielded the anticipated emissions reductions. It is recommended that cities identify metrics to analyze with respect to land use and transportation, and establish a standardized reporting timeframe. A checklist, such as Oakland’s 2015 Implementation Progress Report, could be created by each city and inserted into an online portal to mark whether a mitigation measure has been implemented, the date of implementation, and emissions reductions associated with that measure to date. The data feedback helps create a reinforcing cycle to identify policy measures that reduce emissions and those that need to be modified.

Link policies to mitigation measures. Mitigation measures are too vague and do not correspond with programs or projects that can be implemented and tracked. Currently, many mitigation measures outline steps to “encourage,” “explore,” or “expand” various emissions reductions steps. The Grand Rapids Sustainability Plan outlines clear targets and measurement indicators, which are completely absent from West Palm Beach’s Sustainability Action Plan. Mitigation measures should instead be clearly linked to policy measures, or otherwise separated into ‘Policies’ and ‘Suggestions’ along with the appropriate policy instruments. This would facilitate better implementation and transparency of the legal framework and create more actionable policy measures.

Make data transparent and available to the public. Data should be readily available, downloadable, and transparent to allow for public engagement. The creation of a portal with baseline data, emissions reductions targets, policy measures, and progress reports on the city website would facilitate better public awareness, accountability, and transparency of the climate plan and its implementation. Boulder, Chula Vista, and Oakland have tracking reports and inventories available on their websites, but the data is not standardized. The scope of a central data clearinghouse, such as Carbon Disclosure Project, could be expanded to make data public and transparent.

Incorporate more land use measures. Measures focusing specifically on land use are disproportionately omitted from climate plans. About 17 percent of all measures in plans focus on land use measures. Four cities have adopted no land use measures, and three others have one land use measure each. Where they do occur, they are siloed from transportation measures, even though land use and transportation are intrinsically related. More mitigation measures aimed to reduce the total miles driven would be beneficial in climate plans; the integration of climate plans with regional plans presents opportunities to change zoning regulations to increase mixed-use development, promote the co-location of housing and employment, and ensure basic services are within a given distance of households. Land use measures are more successful when integrated with transportation policies, and combining these types of measures creates a cohesive development trajectory.

Cities have made progress to address climate change through the implementation of Climate Action Plans, and continued efforts by cities to reduce emissions will be critical to meet these existing climate commitments. However, the process and means of implementation need to be improved because many U.S. cities are not meeting their targets. Although this analysis focused on U.S. cities, many of the findings can be extrapolated to cities around the world that face similar urban challenges. On a global scale, land use policies need to be integrated with transportation measures in order to reduce transport-related emissions. This is important for growing cities, particularly in Asia and Africa, which are not yet locked-in to a high-emissions trajectory. Mayors and city officials in these rapidly urbanizing regions can learn from both the successes and challenges that U.S. cities face in implementing effective low-carbon transportation and land use measures.

When world leaders gather for the UN Habitat III conference later this year to design the New Urban Agenda, there is a strong incentive to link the theme of sustainable cities with climate commitments made in Paris. The New Urban Agenda presents a perfect opportunity to share lessons from cities on how to incorporate transportation and land use policies for low-carbon development on a global scale. Addressing climate change in cities necessitates innovative transportation planning that considers not only how people move in cities, but also the land use decisions that greatly impact carbon emissions and the future sustainability of cities.

Emily Wier and Alisa Zomer

New Haven

Acknowledgement: Thank you to CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project) for providing data for this analysis.

about the writer

Alisa Zomer

Alisa Zomer is a Research Fellow at the Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy. Her research focuses on urban climate change governance and sustainability policy at both local and international scales.

Leave a Reply