Step off the street in Suzhou through a small door and you leave behind the bustling cacophony of a modern Chinese city to enter a different world of tranquility and calm, where natural features create a sense of being surrounded by nature in a tiny oasis that is a scholar’s garden. Nine of these gardens in Suzhou have been given special status by UNESCO as outstanding features of the city’s World Heritage Site. Each provides a symbolic microcosm of the natural world within the confines of a single dwelling. They draw on the ancient disciplines of Chinese art and poetry, together with fundamental concepts of landscape, and demonstrate practical application of Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist teachings. The scholar gardens of China illustrate a way of life in harmony with nature and the arts that may still have relevance today.

Although some notable early gardens existed in China over 2000 years ago classical gardens only really started to flourish in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), which has been referred to as China’s first Golden Age. They were developed at a time of relative prosperity, when wealthy scholar-officials were able to create their own special kind of domestic environment as part of the huge advance that was occurring in literature and the arts. One of the greatest influences was the famous 8th century poet Wang Wei, also renowned for his landscape paintings, and his garden Wang Chuan Villa, from which he gained inspiration as both poet and artist. Since that time, poetry and landscape art have remained crucial influences in the design of scholar gardens. During the Tang period, there were over 1000 domestic gardens in the city of Luoyang, and eight Imperial gardens in the capital Xian. The classical house and garden model of the “scholar-official” became well established at this time.

Greater prosperity during the Ming period (1368-1644) led to a proliferation of such gardens. This was the second Golden Age. Suzhou alone had 300 domestic gardens, with many architect-gardeners. Several of the gardens that still exist in Suzhou date from this period. The art of garden design reached new heights with publication of Yuan Ye (On the making of gardens) by Ji Cheng in 1634. The cities of Suzhou and Hangzhou (near modern Shanghai) remained at the forefront of garden design during the Qing period that followed. In the 1760s, the Qian Long Emperor copied many elements of their design, though on a strongly formal Imperial scale, for Beijing’s Summer Palace.

Who were these so-called “scholar-officials” and where did they get their inspiration?

They were members of a select group in Chinese society, the product of an educational system originating in 124 BCE. They had the education, social standing, and financial resources to indulge in intellectual pleasures. Steeped in Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist ethics, these were men with many parts. Poet, artist, musician, calligrapher, and lover of nature were all combined in each man. The art of garden design drew on all of these skills and the scholar-official became central to the development of that art.

Scholar gardens provided a natural retreat in the city. They are essentially urban, making unique use of the ubiquitous town courtyard, which has traditionally been the basis of Chinese urban planning. From the Song dynasty onwards, they provided a welcome retreat for busy scholar-officials, where they could escape from worldly affairs to indulge in creative pleasures. As a microcosm of the natural world in the city, the garden provided the calmness and right conditions for the scholar’s work. The essence of a scholar garden arises from the house and garden being designed as one entity. One merges with the other. The ambience of the house is pervaded by the tranquility of the garden. Yet, there are significant differences between the two spaces that have their origin in the scholar-official’s philosophical lineage.

Confucianism can be described as a moral doctrine governing all aspects of life, including etiquette, social relations, architecture, and even city planning. This may seem to be in direct conflict with Daoism, a religion that seeks The Way through harmony with nature, finding space for contemplation and inner peace. There is a Chinese witticism which says, “Confucianism is the doctrine of the scholar when in office and Daoism the way of life of the scholar when out of office”. So it was in the life of the scholar-official, who designed the house and garden to conform with these different doctrines. Formal and living quarters of the house were arranged according to the requirements of social etiquette, either along one side of the plot or around a central space, or several different spaces, which were landscaped to create harmony with nature. The whole design was influenced by deep-rooted Daoist principles such as Yin and Yang: the need for balance between positive and negative, or contrasting elements. Ancient beliefs were also important, such as Feng shui: the need to conform with long-established practices regarding the ritual orientation of buildings.

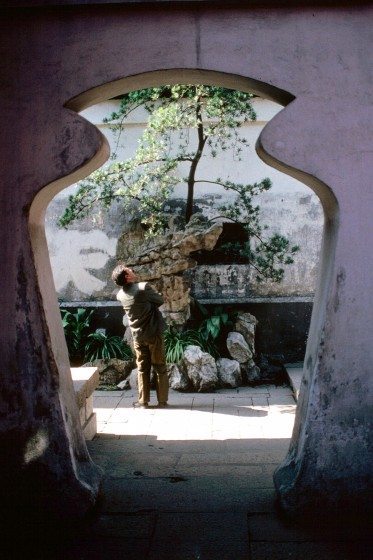

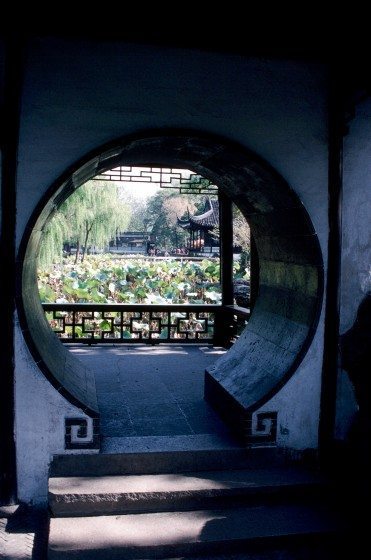

But there are two features of the garden landscape that particularly characterize these scholar gardens. The first is the overall spatial design. The whole garden forms a three dimensional picture through which you can walk. Individual parts are only gradually entered or discovered as you go. The concept of the garden as a series of separate but interconnected parts, to be discovered and enjoyed, is analogous to the unrolling of a Chinese landscape painting. Walls, doors, windows, paths, corridors, and bridges all have a special role in creating a landscape of continuous change and surprise. Often, walls were built for the sole purpose of allowing spectacular views through carefully contrived windows and dramatic moon gates. The 18th century writer Shen Fu said, “Arrange the garden so that when a guest feels he has seen everything, he can suddenly take a turn in the path and have a broad new vista open up before him, or pass through a door in a pavilion only to find that it leads to an entirely new garden”. Many of these gardens are surprisingly small; all this was created within the bounds of a single dwelling, where different vistas were created within the garden that could be seen from carefully selected vantage points. Wherever possible, designers took advantage of a “borrowed view”, such as a distant pagoda framed through a window.

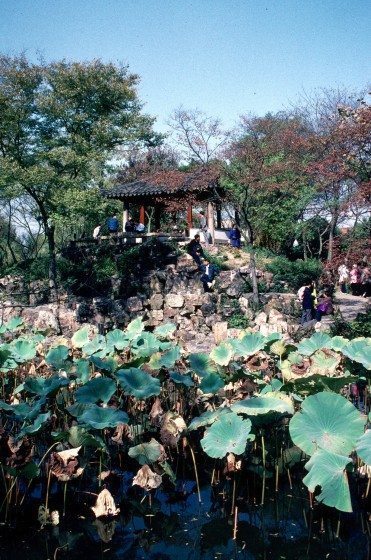

The second feature is the landscape itself. Here we have to go back to early concepts of landscape based on Mountains and Water or Shan Shui. Poetry and landscape painting in China have both drawn inspiration from mountains and water for many centuries, and the phrase Shan Shui itself came to mean landscape. The rugged strength of great mountains set against the softness of water is Yang and Yin at its most profound. They are opposites that complement each other. Water can erode solid rock. So it was not surprising that scholars tried to emulate the great contrasts between rocks and water in creating the micro-landscapes of their gardens. Some of the most highly prized rocks were water worn limestones from Lake Tai that exhibited an intricate and sometimes grotesque degree of natural erosion. The so-called Exquisite Carved Jade Stone in the Yu Yuan garden in Shanghai is one of the most famous examples. The juxtaposition of such stones standing upright as vertical columns above placid pools full of lotus blossoms emphasizes the contrasting nature of mountain and water, and may symbolise, in miniature, the famous mountain landscapes of southern China. Some gardens contain dramatic hard landscapes built from layers of water-worn stone to create the illusion of small mountains—until you pass through the adjacent moon gate to find a completely new vista of lake and lotus leaves. That such contrasts play such a major role in most scholar gardens has led some writers to refer to them as Mountain and Water Gardens. But that name ignores so much else that is fundamental to their ethos.

What about plants? Historically, scholar-officials mainly used plants with long-established symbolic associations, especially those made famous in poetry and art. The palette was quite restricted. Bamboo, lotus, peony, chrysanthemum, plum, and pine were particularly significant. Plants were valued for their contributions during different seasons through their fragrance, colour, shape, or acoustic properties. Examples also included: rose, orchid, loquat, winter sweet, heavenly bamboo, apricot, juniper, sweet-scented cassia, osmanthus, maple, ginkgo, banana, and magnolia. Not only was the range of species very limited, but the total amount of space occupied by plants is relatively small. I have heard western visitors complain at the lack of plants, not recognizing that they are only one part of the philosophical message.

Bamboo growing along a narrow inner courtyard, where it could be seen through a row of windows silhouetted against a white wall, was greatly admired as an artistic feature rather than as a botanical specimen. So it was with virtually all the plants. The placing of an individual tree was carefully chosen to create maximum visual impact when in blossom or showing autumn colours. Others were chosen to catch the natural sounds of wind and rain. Small pavilions were built in which one could sit to experience the sound of raindrops falling on lotus leaves, or drumming on banana leaves. Pine was planted to catch the wind and hold the snow.

Traditional Chinese folklore is full of such associations between plants and the natural elements, and they are frequently reflected in poetry and painting. Though they appear simplistic, these associations were at the very heart of garden design:

By planting flowers one invites butterflies,

by planting pine one invites the wind,

by planting banana trees one invites rain,

and by planting willow trees one invites

cicadas.

I have referred earlier to the great influence that pastoral poetry and landscape art brought to the development of scholar gardens over many centuries. Together, they provided the settings for garden designers to emulate. In addition, there are various buildings of literary and poetic significance within many of the gardens. All these gardens are imbued with a rich heritage stemming from these sources. In some cases, a single line from a revered poem may provide the basis for a whole garden. For example:

“The buzz of a cicada heightened the silence”.

Which brings me to the most significant feature of these gardens, the special sense of space and tranquility within a harmonious whole. To some, the word garden is something of a misnomer. Classical gardens contain many buildings. Some served as living quarters; others were used on more formal occasions. Some provided a place for drinking tea or joining friends for a glass of wine. Others provided a calm environment for scholarly pursuits such as painting, poetry, music, literature, and calligraphy. Yet others provided solitude for contemplation. The whole was bound together by a philosophical message that reflected the ancient Chinese intellectual’s desire to harmonise with nature. In that sense, garden is the right word. For the scholar-official, it was a way of life.

Today, in many Western cities, we have art galleries, poetry groups, literary institutes, botanical gardens, ecology parks, nature reserves, tea-houses, churches, and temples, all disparate and mostly separate. The scholar-official managed to accommodate all of these in his garden, together with a very strong sense of harmony with the natural world. Perhaps we might consider re-establishing the fundamental concepts of the Chinese Classical Garden within the heavily pressurized towns and cities of today by creating a modern equivalent that would encourage harmony between these various activities and with a strong ethos of respect for nature. Many urban nature reserves, town parks, and even city squares provide opportunities for people to gain spiritual refreshment, and in some countries, there is a growing movement to promote quiet gardens. Some of these places do encourage the cultural links that made the scholar gardens so special. We have sculpture parks and many art galleries within botanical gardens. There may be poetry readings. Small groups gather to listen to the dawn chorus.

Perhaps we could embark on a new kind of garden. Not just to provide calm oases in the midst of phrenetic urban life, but something that might have much greater significance. These gardens could provide the basis for a natural philosophy between humankind and nature. They could promote greater understanding of our impacts on the natural world, with a philosophy capable of combating current threats. We need an ethos that respects nature, that draws on our wealth of experience from the arts and sciences. We need it urgently and it needs to be promoted from within the urban environment. We need spaces that provide solitude for contemplation and places that will reverberate with determination. Yes, a new kind of garden with a will to succeed. It is possible that the ethos of the Chinese Classical Garden provides just such a template.

UNESCO protects our cultural heritage through World Heritage Sites, and protects examples of the natural world through Biosphere Reserves, including some in urban areas. Somewhere between these two, there is a need today to provide places in towns and cities—where most of the world’s population now live—that would encourage a more harmonious relationship between humanity and nature, where a philosophy of respect for the natural world could be developed and promoted. We need that philosophy urgently if we are to succeed in stemming the current rate of loss of the world’s biodiversity. Maybe UNESCO could take the lead in promoting such initiatives by creating a new designation for Towns and Cities, in addition to urban Biosphere Reserves, to recognise places that demonstrate the tangible application of such a philosophy in sites of cultural, ecological, and perhaps spiritual value. They would benefit enormously from international recognition. Places for people and nature. That’s what we need.

David Goode

London

Dear David, we are a team providing information online about traveling in China. We find your article very inspiring. Would you like to allow us to reprint your article on our website?

A lovely article and very much had the feel of relaxing in such a garden whilst reading it. This is just the kind of philosophy of holistic human healing space that I’m planning to bring to my conversion of a stables to a holistic equine yard in Bristol! ????????????

This beautiful introduction to Chinese scholar gardens is a timely contribution at a time when the West needs to begin a vitally needed counterbalancing against the domination of rational science. Of course we need sound science in all aspects of life, but in balance. At present science and technology are seen as the keys to our future, driving a survival model rather than taking their proper place within a cultural vision that looks forward to moulding a rich and fulfilling life. Nature has become a commodity.

My own knowledge of Chinese thinking comes from lived experience, from my early life in Hong Kong, when it still held the cultural essence of a part of a very “ancient” China. Both my parents painted and I studied in an artist’s studio under my Master and became a professional traditional Chinese painter at age 12. The vocabulary of nature that we used in composition embodied and spanned the range of human emotions and aspirations.

What I would like to share concerning the context of “harmony with nature and the arts” is that the harmony grew out of an absolute identification with nature. The roots were not respect for nature, ethos or a philosophy though it of course became part of these. From what David has written, I would propose that the West needs two routes – the route of respect and the route of love – to arrive at that identification.

The Chinese, at one time, saw the poet as the highest level of being a human being, manifesting in verse the sublime that comes through inspiration, with a vocabulary anchored in oneness with nature. Indeed, there were many popular films in my childhood, where poor families encouraged their children to aspire to be a poet in order to have a chance of becoming officials of the highest ranks. The quality of poetry – of being at one with the sublime was recognised as the right tone in which to rule, precipitating a sensitive and all encompassing framework for the right way to live. Creating circumstances such as the garden was at the centre of being, permeating work and life. In gardens, the interplay between human expression of emotion using a natural vocabulary through the arts, and manipulating nature artfully to nourish humans through its qualities, sealed that essential identification with nature.

For me, therefore, the words philosophy, ethos, and respect are some distance from the reality of immersion and identification. As I have already said, I feel that the West will need to move through the routes of respect (embodying that within philosophy and ethos) and the route of love in order to come closer to that positioning of at-one-ing. That would unleash a very different kind of engagement with nature within cities. Love of nature is seldom mentioned nowadays, as it is often subject to attack from those with a fearfully rational science-dominated mindset that discredits this vital quality, the essential spark that underlies all motivation to care for and protect nature.

I look forward to the fruits of this delicious food for thought!

Judy Ling Wong CBE