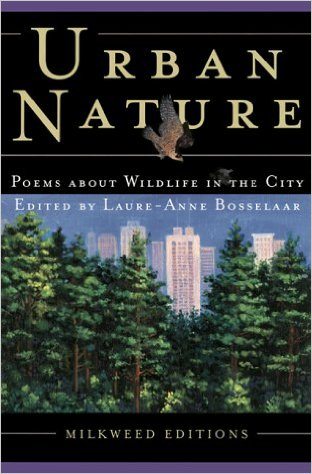

A review of Urban Nature: Poems About Wildlife in the City. 2000. Edited by Laure-Anne Bosselaar. Milkweed Editions, Minneapolis. ISBN: 1571314105. 265 pages. Buy the book.

How can poems advance our understanding of nature in cities? If cities themselves are ecosystems of people, nature, and infrastructure, it follows that these elements can coexist in a balance that yields sustainable, livable, resilient, and just outcomes, even if that synergy is not evident in cities of the world today. Poetry, with its capacity to invert the lexicons of “nature” and “culture” so that they are not artificially divided per our current paradigms, is uniquely positioned to play a role in visioning such cities. By playing words, phrases, sensory evocations, and ideas off each other that would, in the prose discourse of practitioners, remain separate, poetry allows us to discover our future cities through the act of description.

A parking lot can be more than a parking lot. A rusting ship can be more than a symbol of decay. “Nature” encompasses more than a pristine, vegetated space untouched by human influence.

At its most novel, this is how Urban Nature: Poems About Wildlife in the City, edited by Laure-Anne Bosselaar, engages readers. The collection, organized around several themes, occasionally manages to subvert the built vs. natural environment dichotomy, allowing the inextricability of wildlife, landscape, infrastructure, and people to manifest as an emergent property of city life.

Take Carter Revard’s piece, “Christmas Shopping”. The author describes a prosaic scene—pulling into a parking lot near sunset in St. Louis, on a mission to buy Christmas gifts, but emerging unsuccessfully. Where is “nature” here? In another poem, even another poem in this collection, “nature” might have been the suffocated vegetation, mercilessly paved over to make way for a decaying strip mall; the ubiquitous parking lot gulls tussling over a strip of plastic bag; the iridescent shimmer of puddles, a reminder of misplaced fossil fuels.

Instead, Revard catalogues “nature” quite differently:

“—nothing was ordinary; it seemed

we’d floated up into the sunset air all

filled with gold and dark shining, like

being in a cathedral with the moon…”

—Carter Revard

In the subset of poems that looks optimistically on the influence of nature in cities, each author chooses to characterize nature in cities unconventionally.

For example, in Carolyn Miller’s meditation on the unity of things, people sleep “like bees packed in a hive” as, “out on the edge/of land, the ocean rocks and shifts and folds”. Miller draws an emotional connection between people and bees, all simultaneously sleeping in the hive of the city. Likewise, X. J. Kennedy describes pieces of ships in both human and natural terms: the masts become “mechanical conifers” that “redden slow as leaves”.

For example, in Carolyn Miller’s meditation on the unity of things, people sleep “like bees packed in a hive” as, “out on the edge/of land, the ocean rocks and shifts and folds”. Miller draws an emotional connection between people and bees, all simultaneously sleeping in the hive of the city. Likewise, X. J. Kennedy describes pieces of ships in both human and natural terms: the masts become “mechanical conifers” that “redden slow as leaves”.

In the case of “Christmas Shopping”, Revard chooses to see (and say) that “nothing was ordinary”, interrupting his own stream of attempts to describe the scene with this simple message to the reader: a parking lot can be more than a parking lot. Bees and humans share fundamental behaviors. A rusting ship can be more than a symbol of decay. “Nature” encompasses more than a pristine, vegetated space untouched by human influence. “Nature” in cities does is not only decimated.

This is rather a radical proposition for a poet to make, requiring both an open mindedness on the reader’s part and a verisimilitude in the writer’s drawing together of human with natural elements. Based on the binaries with which modern society inculcates us, it is easier to think that nature and cities are diametrically opposed than it is to seek their mutual resonances—hence the relative dearth of anthologies dealing with nature and cities.

Indeed, I could find only one such collection released since “Urban Nature” was published in 2000, relative to the numerous compilations of eco- and urban poetry available today. Even in Urban Nature it is evident that editor Laure-Anne Bosselaar has artfully arranged the collection, managing to highlight the idea of nature in urban contexts while including poems that were not necessarily written to address that theme, and introducing a few household names—Gary Snyder, Mary Oliver, Philip Levine—to bolster the appeal of many critically acclaimed, but lesser-known poets.

After all, to succumb to the notion of cities as the locations of poignant juxtapositions—filth with luxury, gluttony with poverty—is almost inadvertent, because these are the cities that we already know. But placing “nature” and “cities” on opposite ends of a spectrum oversimplifies the rich, chaotic reality of nature in cities, where evolution proceeds under the influence of urbanization, where the chemistry of soils sings of our presence, where children experience nature in the physics of buildings and unprecedented night migrations rather than in forests or camping under the stars. It precludes us from the harder task of envisioning what it would take to make cities sustainable, livable, resilient, and just.

The choice implied in seeing nature and cities as two tones of the same color—where LA’s “Floral loops/Of the freeway express and exchange”, per Gary Snyder’s “Night Song of the Los Angeles Basin”—reminds me of the conscious choice that David Foster Wallace talks about in his famous 2005 commencement speech, “This is Water”. In the speech (and I’m paraphrasing here), Foster Wallace laments how much easier it is for us to walk through the world as though it revolves solely around us, as individuals, than it is for us to choose to project ourselves into the equal complexity of others’ lives. It is a far harder exercise, he says, to imagine that the person driving an obnoxious Hummer on your evening commute does so out of debilitating fear of getting in a car accident, than it is to snippily declare them representatives of everything that is wrong with middle America.

It may very well be, Foster Wallace acknowledges, that the Hummer driver has no legitimate, humanizing reason for her car choice. But this is beside the point: that the practice of opening ourselves to the experiences of others allows us to conceptualize better ways to be human beings. “The alternative”, he says, “is unconsciousness, the default setting, the rat race, the constant gnawing sense of having had, and lost, some infinite thing”.

This “default setting”, as it relates to our association of nature in cities with degradation and a profound sense of loss, is also on display in Urban Nature. Take Mary Oliver’s “Swans on the River Ayr”, in which she writes of the swans: “These ailing spirits clipped to live in cities / Whom we have tamed and made as sad as geese.” Here, city swans are literally deprived by people of their born capacity for flight. Instead, they lead “clipped”, domesticated existences in the dirty shadows of their non-urban counterparts. Oliver links this diminishing to people’s alteration of species and systems. Similar laments appear throughout the anthology in chronicles of species gone extinct (“And so, my dear, unheard, a single Santa Barbara sparrow / Will sing its last spare song”, writes Stephen Yenser in a poem dedicated to his daughter) and bodies crushed violently in the name of automobile-driven progress (“No mercy for that twist of fur, the rush of travelers / streaming home”, writes Madeline Defrees).

These poems are not wrong; indeed, many of them are painfully stunning. But by capturing this one kind of truth—this manifestly obvious, bitter, default kind of truth—of nature in cities, they reinforce the motif of the concrete jungle inhospitable to anything but three-toed pigeons (“Beaks evolved for gutter cracks, handouts. / Hooked toes fit for a witch’s brew”, as in Daniel Tobin’s “Pigeons”).

Honest as they feel, these kinds of poems do not represent the sole truth of nature in cities. There is also the truth we can choose to understand, if we work a little harder: a biophilic moment in Tilden park, where Alison Hawthorne Deming sees the human culture of the San Francisco Bay Area—“the tie-dyed, book-happy city”—seeping into natural forms, where “water sings with the stones” and trees may “have consciousness,/can feel their wood thicken”. There is wonder at the sight of wildlife, adapting and using cityscapes, like Barton Sutter’s Peregrine Falcon, who “folded his wings and dropped, / A living bomb, in his heart-stopping stoop, / One hundred eighty miles an hour headfirst toward the pavement. / And then the opening of wings, the swoop, / The rising up, and all that open sky”.

As we well know, the human species is entering into a new relationship with cities and nature: one where most people’s experiences with natural phenomena will occur, for better or worse, in urban spaces. We are still grappling with how we want those cities to perform on behalf of communities, wildlife, and ecosystems. In doing the kinds of revelatory linguistic turns that make cities natural, and nature in cities whole, Hawthorne Deming, Sutter, Revard, and many others whose work appears in Urban Nature access a new function of poetry: as a tool of choice that we should exercise far more frequently as we continue in the challenging task of visioning future cities.

Laura Booth

New York City

Leave a Reply