According to the United Nations’ sustainable development framework, there are three dimensions of sustainability: (1) economic sustainability (jobs, prosperity, and wealth creation for all); (2) social sustainability (reduced vulnerability to poverty, inequality, and insecurity); and (3) environmental sustainability (production and consumption patterns that respect planetary boundaries) [Note i].

People are using urban nature in simple, incremental, local actions to reconcile the conflicting ideals of social, economic, and environmental sustainability.

On the surface, attaining all three layers of sustainability simultaneously can be elusive and lead to vaguely holistic plans and divergent priorities, keeping in mind that the pace of urbanization is already overwhelming both national and local capacities. On the one hand, the absolute number of the world’s slum population has risen from 650 million in 1990 to 1 billion today; on the other hand, the number of affluent residents is rising, and these tend to generate more emissions than poorer ones, while the impacts of disasters and extreme events are most acutely felt by those who have the least opportunity to offset losses of their homes and losses of paid work [ii].

Part of the criticism targeted at that UN is that, for over a century, governments have implanted an urban development model that is incompatible with the spatial, social, and economic realities of many towns and cities, and which precludes the possibility of introducing robust and locally based alternatives for holistic urban sustainability. However, I contend that, besides the policy and technological shifts that have dominated much of the global discussion, there are cases of urban nature (greening, restoration and protection of ecosystems) being utilized, through simple and incremental actions, to reconcile the conflicting ideals of social, economic, and environmental sustainability. We present two such cases, one from the U.S. and the other from Uganda. The key lesson is that we need to shift from statist, visionary, global-scale thinking about urban sustainability to collaborative, local-level actions that can incrementally set the world in the direction of holistic sustainability.

Urban nature in action in Tampa Bay, Florida, and Kampala, Uganda

One of the inspiring examples of overcoming the fabricated wall between society, environment, and the economy comes from a group of city foresters in the Tampa Bay area—a metropolitan region of west central Florida, U.S.—who have quantified the payoff from pines and palms, olives and oaks. The project was initiated by academics at the University of Florida, who discovered that leafy canopies lower summer air conditioning bills, and that more shade also means less grass: lowering the need to maintain thousands of acres of lawns. From the view of public health, trees contribute to lower asthma rates and birth defects by removing air pollutants.

To get this initiative started, citizens had to change the mindset of city planners in ways that allowed them to realize that a city runs not just on metal, glass, and cement, but on biology and ecology, as well. People provided planners with data about which trees provide the greatest amount of shade, which can be planted closest to pedestrian walkways and parking lots without root growth buckling the pavement, and which species best withstand floods in a city already impacted by sea level rise. A partnership between economists from the University of South Florida; representatives from the USF Tree Campus Advisory Committee; and the UF-IFAS/ Hillsborough Extension Service estimated that the trees save the city nearly U.S. $35 million a year in reduced costs for public health, storm water management, energy savings, prevention of soil erosion, and other services. Further analysis around the straight-dollar costs and benefits revealed to the staff from the City of Tampa that one live oak on the 4200 block of Willow Drive has a 38-inch diameter and a $453 annual payoff [iii]. This project changed the culture of knowledge creation by demonstrating how urban forestry can be leveraged through institutional collaborations, to make urban spaces socially, environmentally, and economically viable.

In Kampala city, Uganda, charcoal is the preferred cooking energy for various reasons: it is affordable for all economic categories of residents earning wages as part of urban employment, particularly for those engaged in circular migration –movement from rural to urban and back to rural for employment. It is substantially more efficient than wood and burns with limited smoke; it has high energy content per unit weight; it has a higher energy density than wood; it is easier to transport than wood; and it can be easily transported to markets far away from the forest. As a result, many Kampalans regard charcoal as a domestic and commercial fuel, without which life in the city can become expensive. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, the total nominal value of household consumption of firewood and charcoal increased by 81.6 percent from 18.0 billion Uganda Shillings in 1996/97 to 32.7 billion Uganda Shillings in 2005/06 [iv]. However, the chain of activities around charcoal continues to be characterized by inefficient production practices and a lack of sustainable supplies of woody biomass. At this rate, the pressure on natural resources in Kampala and the surrounding peri-urban areas is worsened as communities produce more charcoal to meet their income and domestic energy demands.

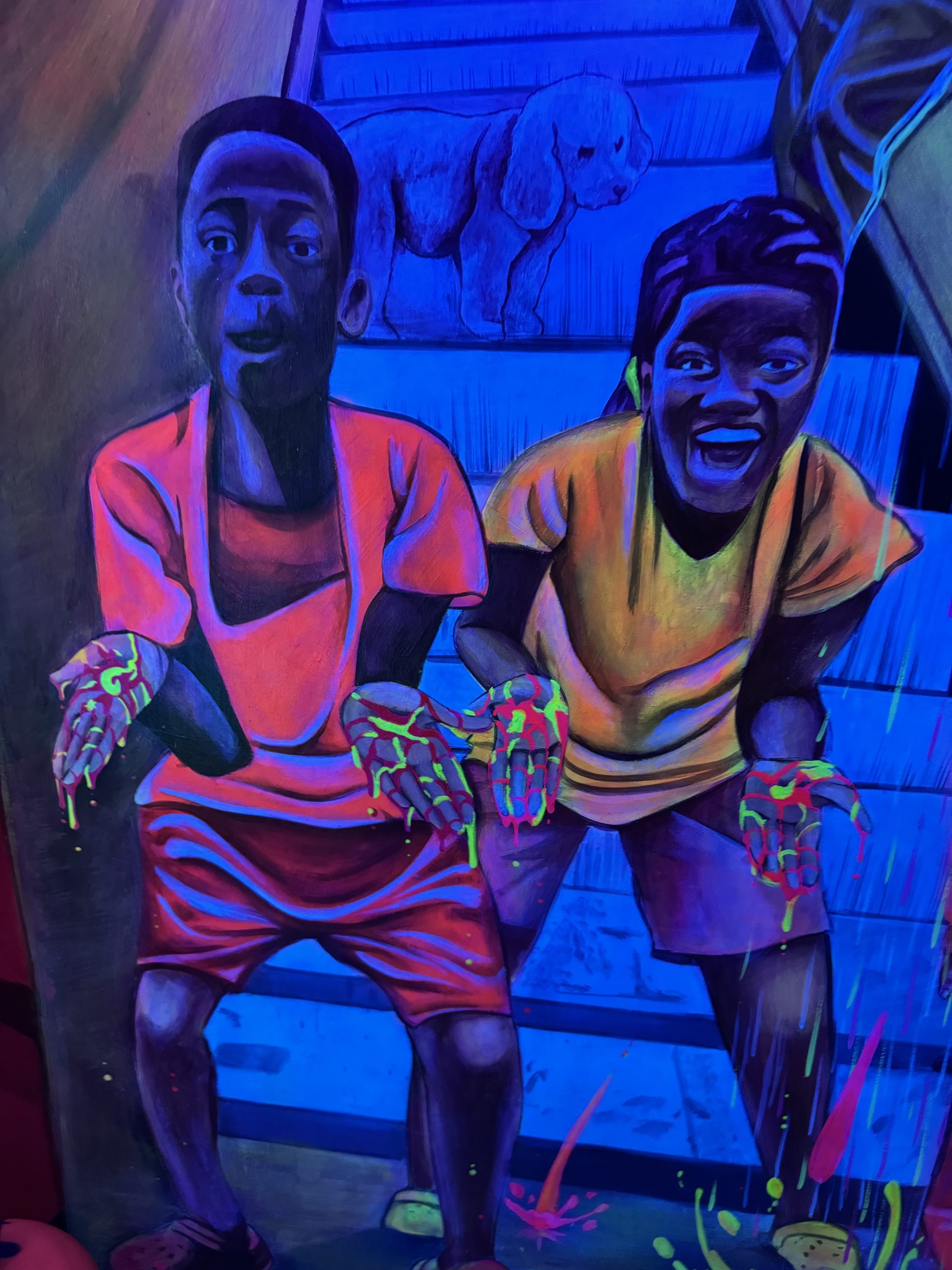

To address the environmental threat of charcoal in ways that bring economic benefit to those at the lowest scale of income, the United Nations Development Programme’s Green Charcoal project is working with the local communities to promote more efficient technologies that enable them to save the environment while still earning from biomass fuels [v]. These technologies include the use of Retort and Casamance Kilns, which are not only environmentally friendly, but are compatible with the expectations of the communities. This is because they generate good quality charcoal using less wood, enabling the benefitting communities to earn more while cutting down fewer trees. The project also promotes the growing of woodlots, so that beneficiaries are able to cut their own trees and save the naturally occurring forests. Where these naturally occurring forests have been reduced, replanting exercises are being encouraged.

I did a transect walk to explore how the primary activities of the project are changing the lives of women. According to Annet, a mother of five aged between 40 and 50 years old living in Kyanja, located ten kilometers from Kampala, she initially spent 35$ on charcoal monthly. This was 50 percent of her income. Since she began to source green charcoal from her relative in Mubende—one of the Green Charcoal project sites found in central Uganda—her expenditure reduced to 18$. By Annet’s account, green charcoal is cheaper and burns longer, saving her time and money. She now puts money saved into her restaurant business that sells food to nearby workers in garages and ongoing residential construction projects. This narrative signifies the vital role urban nature plays in sustainable forest management in rural settings, in terms of collecting fuelwood and developing green products for food, medicine, and domestic energy supply.

Conclusion

While the focus on sustainability in urban areas has primarily focused on environmental issues in large-scale transport, energy, and manufacturing projects, there are varied opportunities to integrate the usefulness of urban nature into socially inclusive, economically attractive, and environmentally sensitive initiatives. Urban nature should therefore have an influence over the design of solutions for a sustainable future, while introducing collaborative and incremental methods at local scales to inform the global discussions.

Buyana Kareem

Kampala

End Notes

i. Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN, 2013). Why the World Needs an Urban Sustainable Development Goal, Note prepared by the SDSN Thematic Group on Sustainable Cities, September 2013

ii. World Bank, 2015. Uganda Economic Update: The Growth Challenge: Can Ugandan Cities Get to Work? , Fifth Edition, Washington, D.C.

iii. Day, J. and Hall, C., 2016. America’s Most Sustainable Cities and Regions: Surviving the 21st Century Megatrends. Springer.

iv. Uganda Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Abstract 2012

Leave a Reply