I find myself choosing the title for this contribution at a time of personal, public, and professional dilemma. Strangely, the dilemma stems from the need to vindicate the question itself.

While it is perfectly acceptable to ask how green, how healthy, how prosperous or how popular a city is, the concept of a sustainable urban food cycle is not yet officially established on most city agendas.

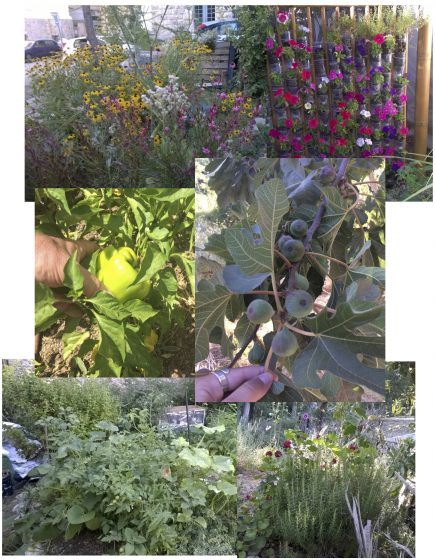

In many cities, food-growing community gardens, urban farms, and rooftop vegetable gardens are perceived as “nice to have”. Yet, in spite of the knowledge that there are many benefits in locally grown food, which are frequently mentioned by contributors to TNOC, urban and peri-urban agriculture are not yet perceived as a “must have” on the required menu for sustainable cities.

In my city, Jerusalem, I established the “Food for Jerusalem” forum just two years ago. We began to seek out and to convene the many stakeholders in and around the city who deal with local food, who are involved either in growing it, supplying it, consuming it, cooking it, or educating children and adults about its importance. The Jerusalem Bioregion Center, working through the Jerusalem Green Fund, had begun to address the issue of community-based urban and peri-urban agriculture after realizing that conventional agriculture constitutes one of the greatest threats to biodiversity, given the way it fills up extensive areas with monoculture crops and encourages the use of pesticides to destroy insects and other threats to the crops. Conventional agriculture poses a threat to consumer health, since a lot of the pesticides that farmers apply are absorbed into the crops and then constitute part of the meals we eat. Genetic engineering of crops is another troubling aspect of large-scale conventional agriculture. While it is true that the jury is still out on genetic engineering, it is undoubtedly not proven to be beneficial. Still, these are the systems that currently provide the enormous amount of food needed to feed the world.

We began to realize that the diverse ways in which food can be grown in an urban setting can not only reduce the negative impact of conventional agriculture on natural resources, but can also contribute to the restoration of habitats for local flora and fauna, if maintained according to the principles of organic farming. Moreover, although we had originally entered the world of local food production through the portal of biodiversity, we soon discovered the many other ways into this arena, which many hope will take center stage in the global conversation about sustainable urbanism, to take place in Quito, Equador, in October 2016 (HABITAT III). The Quito meeting, twenty years on from HABITAT II, will try to serve up the magic formula for sustainable urbanism, and urban food production will be on the agenda for the first time.

The list of benefits from local food production is a long one, but here are a few of them:-

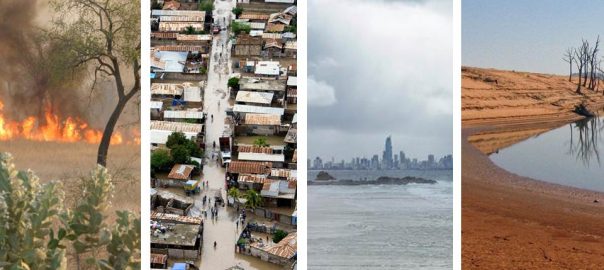

- War, natural disaster, or a failed economy can cut off cities from their food supplies, leaving local communities without food or water. Local food production can contribute to food security.

- Transportation of food into cities accounts for some 30 percent of the emissions of most cities. Local food production can contribute to reducing the city’s ecological footprint.

- Locally grown organic food can be free of pesticides and, therefore, much healthier. Nutrition experts have tested this out and as a result many of them are joining the urban food- growing coalition.

- Kids who learn to grow vegetables at school will be happy to eat them and to focus less on junk food. This is an interesting case of the proof of the “pudding” being in the eating, and there are interesting statistics from schools that have thriving vegetable gardens, where the students are keen to eat what they themselves have grown, admitting that it gives them great pride to take ownership of the vegetable growing process in their schools.

- Neighborhood initiatives such as community gardens not only provide healthy food, but also strengthen community solidarity.

- In many contexts, local food production, together with local hospitality, provides a sound basis for sustainable tourism. This works best when bolstered with local arts, crafts, and music, and of course the local scenery and landscape.

- All of the benefits listed above add up to increased urban resilience

As the “Food for Jerusalem” forum has developed, it is truly remarkable how diverse our stakeholders are. We have schools that are incorporating food-growing in the curriculum of grades 4 and 5, a variety of community gardens, an urban farm that employs youth at risk, senior citizens’ daycare centers, commercial use of roof space for vegetable-growing and “edible neighborhood” initiatives, to mention only a few. It has also become apparent that food growing has the potential to generate cross-boundary collaboration as well, and Israeli and Palestinian communities are beginning to meet and learn best practices from each other.

We have taken the time to meet and argue about the goals of our work in growing food in and around our city. All the stakeholders agreed on the goals, while each one contributes to achieving different aspects of them. The Jerusalem Municipality is a member of the forum, but not its convener. The role of convening the stakeholders in the Food for Jerusalem forum was undertaken by the Jerusalem Bioregion Center, which works throughout the region, regardless of municipal or geopolitical boundaries.

Major goals of the “Food for Jerusalem” initiative, as agreed on by member stakeholders

- Establish and regularly convene a stakeholder forum of food-growing initiatives and foster cooperation among the diverse projects

- Promote national legislation to facilitate rezoning of local land for urban food growing, while fostering cooperation among all levels of government—local, regional and national

- Integrate food production into urban planning in Jerusalem, by means of a development policy that relates both to food growing and biodiversity as part of the ecological infrastructure of the region

- Map and catalog existing initiatives. Identify and develop additional food-growing areas in and around the city

- Investigate the potential for alternative food growing environments (roofs, walls, indoors, etc.)

- Introduce new technologies that are economically and environmentally sustainable for the urban environment.

- Identify, analyze, and quantify the economic, health, and social benefits of developing a local food system

- Strengthen the local economy by promoting initiatives based on the food cycle

- Incorporate the food cycle and healthy eating in the curricula of formal and informal educational frameworks, including active engagement in food-growing

- Establish sustainable water sources for food-growing initiatives in and around Jerusalem

The above goals are admirable, representing a concerted community effort to make the local food cycle sustainable, healthy and secure; that can surely not be faulted. However, if sustainability is really the goal, then what we are doing barely scratches the tip of the proverbial iceberg. As an avid follower of the Food for Cities contributions, I am aware that what is happening in our city is no different from other parts of the world. In the Global North, it is the environmentalists who are preaching urban food-growing and developing all kinds of technologies to grow food horizontally on roofs, vertically on walls, to mention only a few of our antics. In the Global South, dire poverty, and lack of fresh water mean that local food-growing could be the difference between surviving and starving. In fact, both are right, since the environmentalists are aware of the impact of the global food market on emissions, whereas people in survival mode do what they must.

At the HABITAT III global meeting in October, 2016, one of the main focuses will be on how to provide healthy food and clean water for a rapidly increasing world population, most of which will be concentrated in urban settings. All the right decisions and declarations will be made, but they will, of course, be “non-binding”.

This leads me to question the wisdom of the title of this piece, even though I chose it myself. The question that needs to be asked is not “How Edible is My City?”, but “How Can we Brand the Local Food Cycle with a Positive Image?”, thereby ensuring this issue is positioned firmly, securely, and center stage when discussing the ingredients of SDG number 11, the Sustainable and Inclusive Cities goal. We have to think of ways to make cities all over the world vie with each other over the question of where more local food is being produced and consumed. This is going to be a long and difficult haul, but of course it must be noted that the process has already effectively begun, as is evidenced by the increasing number of local food-growing initiatives in and around cities today. It is now up to all of us to help the process to accelerate and to prove the efficacy of a thriving local food cycle in strengthening urban resilience.

Naomi Tsur

Jerusalem

Regarding “How can we market this philosophy?”, perhaps one place to start is by normalizing local/regional food/systems, as a lens within local government. For instance under Mayor Hancock, Denver created/hired the first dedicated staff member (within the Office of Economic Development), as part of it’s Food Vision 2030 efforts. At a recent public meeting I attended, many citizens made the case for how this office can use it’s position to coordinate/restructure existing agencies/efforts within city government and be an advocate for more holistic work around this issue.

Dear Paul

The trouble is that neither Los Angeles nor Philadelphia are nearly as edible as they could and perhaps should be. Who needs to decide to set that goal? Sadly, 1980 is quite a time ago. Has anyone measured the curve of increasing edibility in western cities?

I am perplexed that such an obviously beneficial way to go for cities is not yet mainstream policy. How can we market this philosophy?

Fine article. Agriculture must become a permanent part of the structure, economy, and culture of cities.

Richard Britz wrote the book “Edible Cities” in 1980. My book “Los Angeles: A History of the Future” described how to build a permaculture city, in 1982. http://www.paulglover.org/lahofbook.html I’ve since started the Philadelphia Orchard Project (POP), which has planted 54 orchards here so far. http://www.phillyorchards.org