The Rockefeller Foundation announced its third and final set of its “Resilient Cities”, rounding out a group of 100 cities that have demonstrated success in and commitment to enhancing resilience to climate change and other natural or man-made disasters, among other urban challenges. These cities, along with hundreds of others without the designation, are experimenting with different ways to “climate proof” their infrastructure, to strengthen disaster preparedness and response capabilities, and to integrate considerations of natural hazards and climate change impacts into planning processes. To date, adaptation plans rarely seek to change development patterns or drivers of socio-spatial inequality

In a new research article published in May 2016 by the Journal of Planning Education and Research, we and six other colleagues respond to this research challenge and present the results of a large empirical study examining the equity impacts of land use planning for urban climate adaptation in the Global North and South. We selected eight cities—Boston, New Orleans, Medellin, Santiago, Dhaka, Surat, Manila, and Jakarta—that are at the forefront of adaptation planning. The adaptation interventions these cities have created together represent a spectrum of planning strategies, including developing explicit adaptation plans, linking adaptation to disaster risk reduction or broad efforts to promote resilience, and meeting longstanding infrastructure and developmental backlogs. By and large, these plans seek to reduce the threats of flooding, landslides, and drought through technological fixes—mostly green or grey infrastructure—and land use policy changes. These projects are imagined as a benefiting the city as a whole, but do not explicitly evaluate their impacts on different social groups, particularly in relation to other ongoing societal changes.

As a result, we find that these efforts, while technically rational on their own, can nevertheless exacerbate existing inequalities through “acts of commission” and “acts of omission” that either disproportionately affect or displace disadvantaged groups, or protect and favor the interests of advantaged groups. These mechanisms crop up in places with very dissimilar developmental and environmental conditions. They echo past experiences with land use and infrastructure development, but represent a “double injustice” because disadvantaged groups who contributed the least to global carbon emissions are bearing the brunt of climate change impacts and social costs of adaptation, even as they are being excluded from the benefits of climate adaptation action.

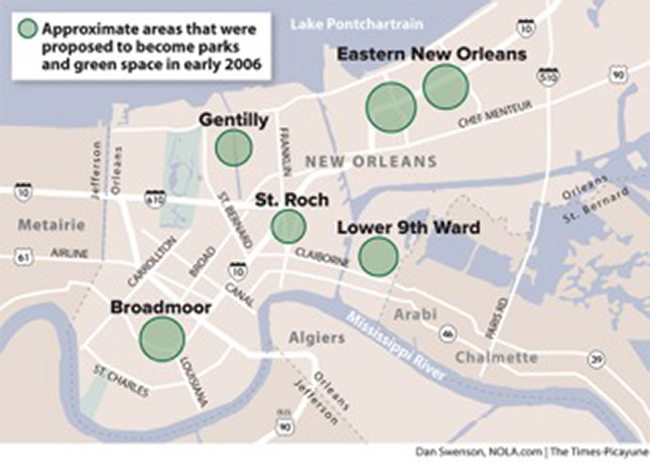

Many cities are investing in engineered infrastructure to reduce flood risks, even though this tends to increase future flood losses as more people build behind the protective infrastructure. These structures provide an illusion of safety in a process known as the levee effect, only to be overtopped during the next record-breaking storm or infrastructure failure. Flooding in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina broke the levees and made palpable the effects of decades of racial segregation that relegated poorer, predominantly black communities to lower-lying areas such as the Lower Ninth Ward, Gentilly, and New Orleans East. Even worse, the immediate planning processes post-disaster proposed to “shrink the footprint of the city” by converting some of the worse hit (black) communities to parks that would create new ecological buffers for more privileged neighborhoods. The proposal, logical from a purely ecological planning perspective, produced an outcry against the now infamous “Green Dot Map” as a thinly veiled and unethical attempt to remove poor blacks from New Orleans.

Planning has since shifted to community-scale rebuilding on the one hand, and rebuilding massive new levees on the other, which controversially removes much of New Orleans from the FEMA flood map. New urban plans and design strategies also try to reintegrate water into the fabric of the city through strategies such as rain gardens and bioswales to infiltrate and slow stormwater. However, at no time has the municipality fundamentally included community-based planning into its own planning practice and decision-making, nor changed its land use planning for greater socio-economic and racial integration, even as gentrification of former low-income and black neighborhoods, such as Tremé, exacerbates racial divides.

Across the world in Southeast Asia, Jakarta, Manila, and Dhaka echo this pattern. In Indonesia, the government responded to Jakarta’s devastating floods in 2007 by proposing a new city for 1.5 million people on a massive series of seawalls in the Jakarta Bay in the shape of the country’s national symbol, the Great Garuda. The plan, supported by the Dutch government, also calls for the eviction of extensive kampong settlements along the city’s many riverbanks in order to widen and dredge the canals and rivers, without addressing existing and new housing needs for the poor. In Manila, the government approved a flood risk management master plan after a 2009 typhoon flooded as much of 70 percent of the metro area that, among numerous grey and green infrastructure proposals, would remove 100,000 poor households (as many as 800,000 people) from alongside waterways. In Dhaka, embankments in the western side of the city built in the 1990s were designed without consulting residents, caused major disruptions to adjacent communities, and excluded extensive low-income settlements.

Such climate adaptation projects discriminate in the application of land use rules between wealthier groups who have greater political clout and access and low-income and informal residents without land title and access to decision-making structures. In Medellin, the city proposed a Metropolitan Green Belt to protect the valley’s upland slopes to reduce landslide risks. Although over 230,000 residents live within what has been designated the protected area, higher-income neighborhoods are not being resettled and indeed are being allowed to expand, while thousands of lower-income residents have been designated as being located in areas of “non-recoverable risk” that will be relocated to housing towers in the valley. In Manila, no one is permitted to develop within three meters of waterways, but the government enforces the law where it is easiest to do so: in informal settlements, even though it has permitted 41 percent of the region’s waterways to be filled over the years for roads, malls, and middle and upper-class housing.

Adaptation projects are often done without participatory processes and values that prioritize the interests of the most disadvantaged. From the outset, the definition of the problem (flooding, landslides) and the choice of strategies (green or grey infrastructure) obscures the root causes of vulnerability, such as income inequality and the right to housing, as Fadi Hamdan explored in his TNOC post. Such proposals indicate that hazard risk is not an intrinsic physical condition, but a value judgment about the kind of development and people who can pay for the protective infrastructure. At best, disadvantaged communities can stop particular proposals, like the Green Dot Map, but often have little voice in the design and implementation of overarching strategies. Where planning processes do emphasize public participation—as Santiago’s climate adaptation strategy did—facilitators nevertheless prioritize producing consensus around a narrow set of issues over addressing underlying causes of inequitable access to water and the capture of natural resources by elite private corporations.

Finally, the costs of climate adaptation have led many cities to rely on private sector leadership. In Surat, India, the Rockefeller Foundation supported a six-year resiliency planning process that began by cataloguing the vulnerability of the city’s 400 slums in low-lying areas, but ultimately did little to consult local communities and pursued infrastructure redevelopment strategies that focused on protecting refineries and textile mills. In Boston, the city developed proposals for public assets and worked with the business community to develop proposals for private property owners to respond to flooding and storm surge. Downtown asset management firms developed relationships with emergency service providers for direct access during disasters, invested in temporary flood barriers, and institutionalized these strategies through industry plans and reports. By contrast, only one low-income community in the city has begun adaptation planning with the support of the Kresge Foundation. One approach in Dhaka—to facilitate autonomous adaptation by letting private developers landfill areas for middle and upper class housing—has worsened flooding in surrounding areas and provides a cautionary tale for many cities beginning down this road. As Richard Friend’s TNOC blog noted, market-based solutions cannot forge transformative and inclusive urban futures, especially if they are implemented without state control or oversight.

In each of these four areas—the provision of infrastructure, enforcement of land use regulations, inclusion in the planning process, and engagement with the private sector—we find acts of commission and acts of omission. Acts of commission occur when infrastructure investments, land use regulations, or new protected areas disproportionately displace disadvantaged groups to areas that are themselves unsafe or do not allow communities to thrive, create long-term environmental gentrification, prioritize elite groups’ agendas and definitions of vulnerability, or support disaster capitalism rather than community development. Conversely, acts of omission are plans that protect economically valuable areas over low-income or minority neighborhoods, frame adaptation as a private responsibility rather than a public good, avoid enforcing land use regulations against wealthy communities, or fail to involve affected communities in the process or recognize their alternative proposals for development. These processes operate within cities, but are further exacerbated by unequal planning capacities between cities in a region, and between regions or countries. Left unabated, these mechanisms help form ecological enclaves of the resilient “haves” and vulnerable “have nots”.

Certainly not all adaptation projects produce such unequal and unjust outcomes, and the Rockefeller Foundation’s own framework for resilience and accompanying package of technical assistance to its 100 resilient cities calls out social justice. Nevertheless, our research presents the first effort to comparatively assess how land use planning for climate adaptation can exacerbate existing inequalities. It demonstrates the need for further critical assessments of emerging adaptation plans, and to open up difficult conversations around the sometimes competing priorities for the expansion of affordable housing, urban densification in post-industrial waterfront and coastal communities—not least to reduce carbon emissions, adaptation to climate impacts, community empowerment, and municipal fiscal health.

A fundamental challenge is that, to date, adaptation plans rarely seek to change development patterns or drivers of socio-spatial inequality. Where adaptation plans do call for equity and justice, as many California state documents do, the language tends to be vague and goal-oriented, making them difficult to be enforced or measured. Some cities, such as Baltimore, have emphasized participatory planning processes that better engage disadvantaged communities. These strategies and principles for environmental justice, from the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991 and the 1994 U.S. Executive Order 12898, provide a basis for thinking about equity and justice in adaptation planning. But there is an urgent need to find examples where climate adaptation and resilience projects have moved towards more equitable outcomes and to identify specific normative principles, design strategies, and evaluative outcome metrics for alternative adaptation strategies that highlight equity and justice.

Linda Shi and Isabelle Anguelovski

Cambridge and Barcelona

In Memoriam: This research honors and builds upon the work of Professor JoAnn Carmin, whose scholarship pioneered the field of urban climate adaptation governance.

about the writer

Isabelle Michele Sophie Anguelovski

Isabelle Anguelovski is a Senior Researcher at the Institute for Environmental Science and Technology at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. She is a social scientist trained in urban and environmental planning and coordinator of the research line Cities and Environmental Justice.

Leave a Reply