Our world is rapidly urbanizing at a rate that is unprecedented in the history of human kind. In 2014, the urban population reached nearly 4 billion people and it is predicted to gain an additional 2.5 billion people, most of whom will reside in African and Asian cities. Although the corresponding urban land cover represents only 1 to 3 percent of the planet, cities are centers of significant power and influence on people, society, economies, and natural resources. The rapid expansion of the global urban population has resulted in more intensification, densification, and outward expansion of existing cities and the creation of new cities.

There are now numerous mega-cities in the world such as Tokyo, Delhi, New York, Mexico City, and Shanghai that support populations of upwards of 20 million people at densities of over 120,000 people per km2. As cities continue to grow, they stress social, economic, and ecological systems, for they require large amounts of resources, strain transport and other infrastructure, and often create ‘concrete jungles’ that lack greenery and open spaces. In 2011, a UN Global Report on Human Settlements warned that the future synergistic interactions between urbanization and global climate change ‘…threaten the quality of life, and the economic and social stability of human societies around the globe’ making them two of the fundamental themes of the 21st century. The magnitude of the global impact of urbanization has been highlighted in a recent issue of Science (20 May 2016) that features a special section entitled ‘Urban Planet’.

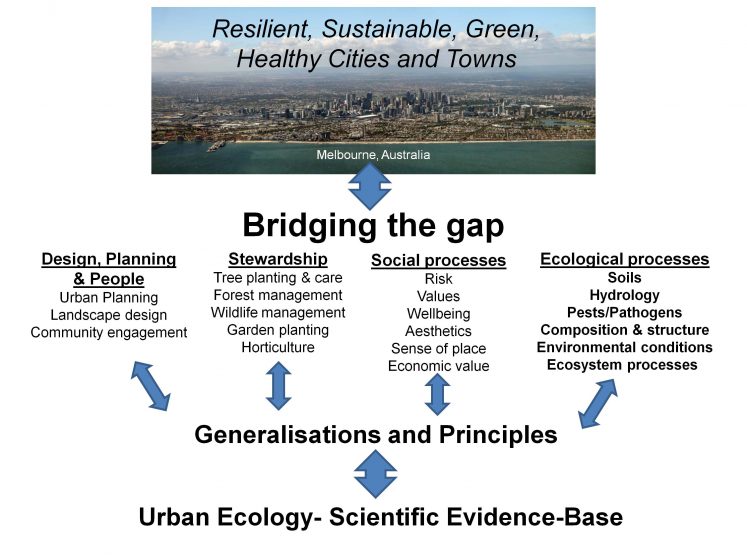

The discipline of urban ecology arose in the late 1990s, motivated in part by the rapid rate of urbanization and its often negative impacts on humans and the planet. It was formed through an amalgamation of a diversity of disciplines including geography, ecology, sociology, architecture, planning, and human health, to name a few. The science of urban ecology is primarily focused on increasing our understanding of the ecological and human dimensions of the structure and function of urban ecosystems. Practitioners are engaged in developing evidence-based designs, plans, and construction methods to create and maintain sustainable and resilient cities. We feel that the creation of more livable and healthy cities in the future can only be realized through the synergies achieved by bridging the gap between the science and practice of urban ecology.

The discipline of urban ecology arose in the late 1990s, motivated in part by the rapid rate of urbanization and its often negative impacts on humans and the planet. It was formed through an amalgamation of a diversity of disciplines including geography, ecology, sociology, architecture, planning, and human health, to name a few. The science of urban ecology is primarily focused on increasing our understanding of the ecological and human dimensions of the structure and function of urban ecosystems. Practitioners are engaged in developing evidence-based designs, plans, and construction methods to create and maintain sustainable and resilient cities. We feel that the creation of more livable and healthy cities in the future can only be realized through the synergies achieved by bridging the gap between the science and practice of urban ecology.

Urban ecology: from emergence to reformation

Today, large and small cities are struggling to address myriad environmental and social challenges that impact human health and well-being, including poor waste management systems, inadequate energy supplies, poor food quality and availability, as well as environmental problems such as air, soil, and water pollution. In addition, there are direct and indirect effects of the creation of more urban land on local, regional, and global biodiversity and critical ecosystems.

Over the last 20 years, discontent has grown amongst urban dwellers worldwide, accompanying the erosion of their quality of life and its impact on their well-being. A well publicized example of this occurred in 2013 in Istanbul, when a large protest erupted over the building of a shopping centre in one of its most famous parks (Gezi Park). The residents were angry and frustrated at the loss of one of the last green spaces in that part of the city.

Other examples of the growing environmental activism in urban centres around the globe include the recent mass protests in China and Vietnam by residents who do not want to live near industrial plants that pollute the environment. We propose these are examples of a new urban reformation that is spreading across the globe, which demands changes in how we create new cities and expand existing ones. This change in approach (i.e., reformation) explicitly calls for the inclusion of principles of ecology and social justice in the development process.

To address and mitigate the social and environmental challenges associated with the rapid urbanization of our planet, urban ecology researchers and practitioners are synthesizing ecological and social data from cities around the world to identify ecological and social generalizations, principles, and theories that can help guide new approaches to design, construction, and management. Historically, cities have been created and managed based on best practices in planning and engineering, as well as the architectural and design standards of the day. Thus, modern cities have essentially been built and managed in such a way that people, buildings, transportation systems, water, energy, nature, and economic systems were studied, planned, designed, and managed separately in professional, academic, and administrative silos. The adoption of a more holistic or system approach that explicitly includes ecological and social justice principles thus forms the cornerstone of this new urban ecology reformation.

Bridging the gap between science and practice

Urban ecology research has commonly focused on identifying mitigation and adaptation actions to help reduce the negative impacts of human activities. Many cities around the globe are actively working to improve the health, liveability, resilience, and sustainability of their city, and there are several global initiatives to support these efforts, including the C40 Cities, 100 Resilient Cities and the ICLEI Cities Biodiversity Centre’s Local Action for Biodiversity (LAB) program. Research partnerships are being developed to inform future actions on a diversity of themes, including understanding, protecting, and enhancing biodiversity; creating and managing ecological linkages; and creating biodiversity-friendly environments by minimizing negative impacts on animals, plants, soils, and ecosystems. Public participation initiatives are encouraging and assisting the public to experience and value biodiversity and urban ecology in general. By incorporating these elements into mitigation and adaptation strategies, they are effectively bridging the gap between the science and practice of urban ecology (Fig 1). Worldwide, there are a number of examples of cities that are active participants in the new urban ecology reformation including Baltimore (US), Chicago (US), Curitiba (BR), Durban (SA), London (UK), Phoenix (US), Portland (US), Sydney (AU) and Vancouver (CA) to name a few.

One example of a city which is actively participating in all of the global initiatives, as well as providing leadership in the areas of research partnerships and public participation, is the City of Melbourne, Australia. To date, the City of Melbourne’s actions to create and maintain a green, healthy, liveable, and resilient city include a number of strategies and initiatives that cover climate change, open space, water, vegetation, and biodiversity. The city’s Urban Forest Strategy has received international recognition, for both the approach and targets it sets for its highly developed municipality. The City of Melbourne has also worked to share this knowledge more widely through the “How to Grow an Urban Forest” guide, which was developed and delivered in conjunction with 202020 Vision program. It is clear to us that Melbourne is one of the leaders in this new urban ecology reformation, and there are many other cities in Australia that have also joined this movement. While we still face many challenges associated with an “Urban Planet”, it is clear that the discipline of urban ecology and the many research-practice, and public-private partnerships that utilize this knowledge will play a leading role in our efforts to reduce the impacts of urbanization on urban dwellers and the environment, and create a more promising outlook for the future of our planet.

Mark McDonnell, Ian MacGregor-Fors, and Amy Hahs

Melbourne, Veracruz, and Parkville

about the writer

Ian MacGregor-Fors

Ian MacGregor-Fors is a researcher at INECOL (Mexico). His interests are broad, but he focuses on the responses of wildlife species to urbanization.

about the writer

Amy Hahs

Dr Amy Hahs is an urban ecologist who is interested in understanding how urban landscapes impact local ecology, and how we can use this information to create better cities and towns for biodiversity and people. She is Director of Urban Ecology in Action, a newly established business working towards the development of green, healthy cities and towns, and the conservation of resilient ecological systems in areas where people live and work.

Can someone give me names of architects that are in 2025, of actively participating in increasing the presence of trees/woods in central urban settings; and how this influences their architectural designs, I am in interested in the inclusion of real woods in urban centers , and not only miniature Miyoaki style woods.

Thank you in advance for your help.

I would like to ask one of you authors if you could suggest any article, paper, book focused on the possible abandon of traditional zoo formats within cities by way of a different urban planning that would integrate nature corridors/areas within cities, allowing at least regional species, if not ‘exotic’ species to ‘roam through parts of a city without hampering human life within or without the city and yet would greatly transform our present notion of what a city looks like. I am greatly interested in anything approaching the subject. I wrote an essay on the change of large cities ‘The Big city as Garden of Eden’ in The Montreal Review and am now interested in knowing about novel views concerning the change from urban zoo to ‘ planned urban ranging wildlife’. I thank you in advance for your suggested sources on the subject.