For a state surrounded by fresh water, Michigan, in the northern United States, certainly has had its share of water woes lately. Michigan’s water has always been our crowning glory; from our geography to our automobile license plates, the Great Lakes define us. As we hit the height of summer, you can hear the State’s “Pure Michigan” advertising campaign everywhere as it beckons visitors to the mitten-shaped state surrounded by five immense, freshwater lakes.

Michigan and its neighbors should return to the idea of Great Lakes water as a Commons to protect fresh water in the region.

Unfortunately, on most days, you can also find news about lead-poisoned water in Flint, Detroit’s water shut-offs, beach closings caused by contaminated water, or the threat of water exports. Add to this the decades-old issues of industrial and agricultural pollutants in the watershed, combined sewer overflows, and the emerging issues of stormwater assessments and water access for agriculture and landscape maintenance, and it becomes abundantly clear that water is a major issue in the Great Lakes State.

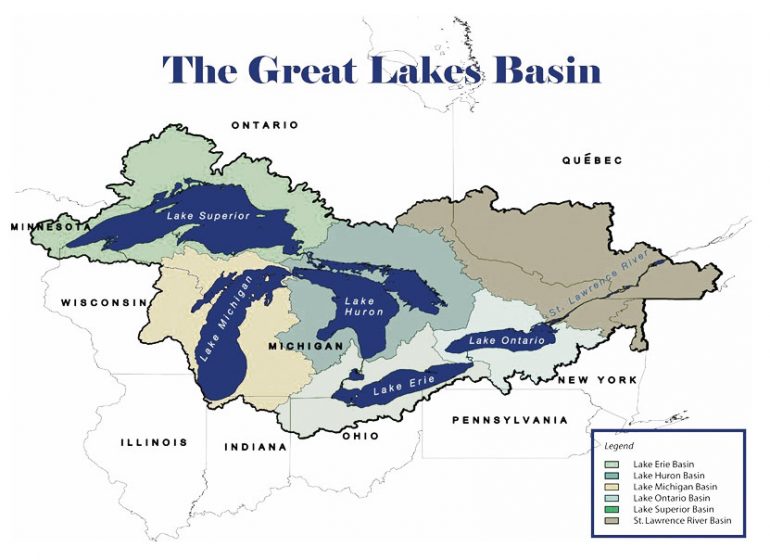

The Great Lakes that surround Michigan’s peninsulas contain 20 percent of the fresh water surface on the planet. The lakes rest on the border of the United States and Canada, and the Great Lakes basin is home to about 34 million people who depend on these waters for drinking. The five Great Lakes were formed 10,000 years ago as the glacier that covered the northern U.S. receded and melted, leaving water-filled depressions in its wake. Given that these lakes hold six quadrillion gallons of water, it is easy to see how generations of people have viewed the great lakes as a resource that could never be compromised or exhausted. In fact, in the early part of the 20th century, the lakes were intentionally used to dispose of all kinds of waste. Lake Erie was probably the most seriously impacted by this practice. Shallower and smaller than the other lakes, Lake Erie became so polluted that one of its tributaries (the Cuyahoga River) famously caught fire in 1969. Rivers in Chicago, Buffalo, and Detroit burned as well, a situation chronicled by John Hartig in his book, Burning Rivers – Revival of the Four Urban-Industrial Rivers that Caught on Fire. In recent decades, a concerted effort has been made to clean up the Great Lakes, as well as the watersheds within the Great Lakes basin after the Clean Water Act of 1972 set the stage for continuous progress toward making sure that our fresh water resources are protected.

Conservation is essential, but questions of access have been grabbing the spotlight recently. Waukesha, Wisconsin was recently granted permission to siphon water from Lake Michigan for its residents, re-igniting a controversy that has been simmering since 1999, when the Canadian government revoked a permit that would have allowed millions of gallons of water from Lake Superior to be shipped to China. That protest still echoes in the voices of Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation, which is calling attention to a Nestle water-bottling plant in Stanwood, MI.

Another kind of access issue has risen in Detroit, Michigan where decades of inconsistent enforcement and unpaid bills led the water department to act on thousands of shut off-notices sent to residents during the summer of 2014. Water and sewerage costs in that city are also threatening the future of urban agriculture, long held up as one of the mechanisms of Detroit’s burgeoning comeback. In Flint, Michigan, residents discovered in late 2015 that their drinking water had been infused with lead after a series of governmental interventions. Since then, water testing across the country has revealed that the presence of lead in urban drinking water is a widespread problem, leading to questions of safety and environmental justice in access to water.

In June 2016, council members of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact (“the Great Lake Compact”) voted to allow the city of Waukesha, Wisconsin (a city lying outside of the Great Lakes watershed), to purchase 8.2 million gallons of water per day from Oak Creek Wisconsin (a city located inside the Great Lakes watershed), which draws its water from Lake Michigan. Waukesha applied for the diversion because its water is currently drawn from a deep-water aquifer with unsafe levels of radium. Radium is a naturally occurring element common in ground water pumped from sandstone aquifers. As an aquifer is drained over time, water is pumped from deeper in the aquifer, increasing the amount of radium dissolved in the water. Lifetime exposure to elevated radium levels can result in an increased risk for cancer.

The Great Lakes Compact was formed in 2008 by the eight states and two Canadian provinces that border the Great lakes. The Compact regulates water conservation and uses in the Great Lakes Basin and provides that any diversion must be approved by a unanimous vote of the council members. The council is comprised of the governors of all eight member-states. Never before had the council voted to allow a diversion of water to a community outside of the Great Lakes Basin. The use was allowed in this case because the city of Waukesha is located in a county that includes property within the watershed, and the Council determined that Waukesha had exhausted its alternatives. Additionally, the city promised that 100 percent of the water it used would be treated and returned to the lake, convincing the Council that diversion was an acceptable option.

Opponents to Waukesha’s petition were not convinced that Waukesha had exhausted its options, noting that water can be treated to neutralize radium. They cited concerns that the treated water, which will be returned to Lake Huron via the Root River, could be contaminated by the chemicals used to treat it after use, harming both the Root River and Lake Michigan. They also argued that the diversion creates a dangerous precedent in a time when fresh water is becoming increasingly coveted around the world.

As the world’s population grows, fresh water will continue to grow in value. Great Lakes water has already had decades of diversion pressure. In fact, the Great Lakes Compact was created to regulate use of Great Lakes water after several American and Canadian companies sought to export lake water for sale as drinking water. In one instance, a Canadian company planned to sell 160 million gallons of Lake Superior water to a client in China. In another instance, a partnership between a Canadian and a U.S. company was formed to siphon five billion gallons of fresh water a year from a glacier-fed lake in Sitka, Alaska. This water would also have been shipped in bulk to China for drinking. In 1999, the Canadian government revoked both permits before the planned diversion. This narrow miss alerted the states and provinces surrounding the Great Lakes to a gap in regulatory strategies, leading to a discussion of whether Great Lakes water should be considered a Commons protected by law as a Public Trust that is the property of the public, which cannot be denied access to it. As proposed by Maude Barlow, National Chairperson of The Council of Canadians, in her paper “Our Great Lakes Commons: A People’s Plan to Protect the Great Lakes Forever”:

“A Great Lakes Basin Commons would reject the view that the primary function of the Great Lakes is to promote the interests of industry and the powerful and give them preferential access to the Lakes’ bounties. It would embrace the belief that the Great Lakes form an integrated ecosystem with resources that are to be equitably shared and carefully managed for the good of the whole community.”

The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact was signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2008, but like most policy initiatives, it includes a variety of exceptions and loopholes that prevent it from creating a Great Lakes Commons as Barlow proposes. One of these loopholes permits water from the Great Lakes from being labeled a “product,” allowing it to be bottled and then sold outside of the Great Lakes basin. This loophole makes it possible for Nestle Corporation to operate a bottling plant in Stanwood, MI, which bottles water from Lake Michigan aquifers in Western Michigan for sale as Ice Mountain drinking water.

Noting environmental issues that this practice was generating in the watershed, the conservation group, Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation, brought suit against the corporation in 2000 to stop a planned expansion of Nestle’s operations. This suit resulted in a 2009 settlement that permanently limits the amounts and rate of extraction of water by Nestle’s operation. However, questions about the public policy implication of allowing a private company to bottle and profit from the sale of a public resource have continued even after the settlement. The discussion reached a boiling point once again in late 2015 as the citizens of Flint, Michigan found themselves turning to the bottled water for sale in their local stores as an alternative to the lead-infused water that was flowing from their taps.

Flint residents have had a particularly painful 24-month lesson in the value of clean, safe drinking water. For years, Flint had received its water from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, sourced from Lake Huron. In April, 2014, Flint’s water source was switched to the Flint River in a cost-saving maneuver orchestrated by an Emergency Manager appointed by Michigan’s governor. Within two weeks, residents were complaining about water quality, noting skin rashes, as well as discoloration and poor taste of the water. For months thereafter, governmental officials—ranging from the Mayor’s office, to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality to the federal Environmental Protection Agency—assured Flint’s citizens that their water was safe. (Check out the timeline for the Flint Water Crisis here.) Health concerns escalated, including an outbreak of Legionnaires Disease, skin rashes, and finally findings of escalated lead levels in blood tests of Flint children.

All of these problems were eventually traced to the switch to Flint River water and the subsequent decisions about how to prepare the water for public consumption. Like many inland rivers in northern urban areas, Flint River water is highly corrosive as a result of a high concentration of chloride ions present in water that has filtered through soil saturated with salt from winter road de-icing practices. Ignoring the chemistry of the water, the City of Flint made a cost-saving decision not to add a common anti-corrosive agent to it. As a result, the water corroded pipes containing lead or lead solder, which were a component of Flint’s water infrastructure. Lead leached from those pipes into drinking water, causing elevated blood lead levels and a variety of other illnesses. Meanwhile, Flint residents were still being charged for the lead-infused tap water, and they were also purchasing bottled water for use in their homes. When news of Flint’s poisoned water hit the media, the country rose to support Flint, donating millions of bottles of water for distribution. Many corporate citizens, including Nestle Corporation, joined the effort to provide safe drinking water to the citizens of Flint.

Photos of Flint water aid inevitably showed cases upon cases of bottled water. This led to more questions: Why was Nestle allowed to pump clean public water for free in order to bottle and sell it when residents were forced to pay for poisoned water? Why were Flint residents forced to keep paying for water they couldn’t use? How could this happen in a city located only 70 miles from Lake Huron, one of the largest sources of fresh water on the planet? Shouldn’t residents have the same right as Nestle to pump clean, safe drinking water for free?

In April 2014, residents of Detroit, Michigan found themselves asking that very same question as they experienced another kind of water crisis. At that time, the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department announced its intent to turn off water service to 140,000 Detroit residents for non-payment of water bills. News of the shut-offs spread worldwide and the conversation quickly turned to whether water was a service or a human right. Protests were organized, and the United Nations declared Detroit the site of an international humanitarian emergency. Eventually, the City of Detroit issued a moratorium on shut-offs and created new programs to aid customers with delinquent water bills. Still, for some residents, there simply is not enough aid and each spring more shut-offs are announced; 50,000 homes have been disconnected so far, and the question of whether water is a human right continues to be debated.

In an ironic twist of fate, many of these same Detroit residents are dealing with another kind of water problem: flood waters that invade their homes during heavy rains. Detroit has a combined sewer system, meaning that its sanitary sewers and its storm sewers combine on the way to Detroit’s water treatment facilities. This system is aging, and in many areas it is inadequate. The result is that in heavy rains, stormwater overwhelms the system, causing it to overflow. This sends water from the street, and water from residents’ sinks, showers, and toilets flooding into the streets, basements, and rivers of the city. Detroit has been ordered to eliminate these so-called combined sewer overflows (or CSOs) and it has begun to implement solutions. Still, many of the same residents who are getting their drinking water shut off are also forced to deal with unwanted stormwater whenever it storms.

Nature, in the form of green infrastructure, offers one solution to this problem. The Detroit Water and Sewerage Department has begun to install a variety of storm water reclamation treatments on vacant property in areas where CSOs are common. The Department is working with communities and non-profit groups like The Greening of Detroit to plant trees, build roadside bioswales, and create vacant lot plantings designed to work like giant sponges, all with the objective of absorbing or diverting stormwater before it reaches street-side storm sewers.

These treatments are useful as models for urban property owners who want to implement similar treatments on their own property. The desire for such beneficial landscaping, especially in commercial and industrial settings, is growing and should continue to escalate as a result of a stormwater surcharge that will soon be imposed on all property owners. The surcharge will be based on the ratio of impervious to pervious surface on a single piece of property. Where properties are covered by large buildings and acres of asphalt or concrete parking lots, these fees will be astronomical. Property owners will be induced to reduce the amount of runoff from the impervious surfaces on their property, and solutions such as parking lot bioswales, green roofs, and pervious pavers are all cost-saving opportunities just waiting to be planted.

In fact, much of Detroit is in the process of being planted. Detroiters have realized that with abandonment comes space, and with space comes opportunity. By planting their vacant spaces with forests, prairies, bioswales, and farms, Detroiters are making their property more valuable and their lives better. But they are also realizing that all of these solutions require water, and in Detroit, the water they need to keep their plantings alive is safe and clean and available, but it isn’t free. In fact, it’s pretty expensive. Water bills for landscaping and agriculture can run to thousands of dollars a month, and even in the off-season, the charge for sewerage is substantial. At one of The Greening of Detroit’s farms, pictured above, a $20 monthly water usage fee garnered a $596 sewerage fee. For a community organization or a small-scale farmer, an expense like this can quickly put an opportunity out of reach. In a city where there are plenty of social issues to concern residents, one local farmer recently listed his water bill as his biggest worry.

This is a particularly poignant problem because urban agriculture has been hailed as a solution to so many urban ailments. In Detroit, urban farming has been lauded as the answer to a well-publicized food security problem, as well as a mechanism to connect community residents and engage them in the civic revitalization of their city. It has also been recognized as a contributor to Detroit’s economic revitalization, acting as a beacon that has attracted young chefs and visionary restaurateurs to make Detroit one of the country’s hottest food scenes. In Flint, the role of urban agriculture is even more important. In a city that is as distressed as Detroit ever was, where food security is still an issue, and where a generation of children will suffer from the effects of lead poisoning, urban agriculture has the potential to both feed and heal the population.

A healthy diet rich in vegetables and leafy greens provides iron, calcium, and vitamin C that can keep lead from absorbing into the body. Increasing the amount of vegetables and herbs such as garlic, cilantro, tomatoes, onions, and green peppers after lead poisoning can create a chelating effect, helping to remove lead that has already been absorbed. These same vegetables can help prevent lead from absorbing into the blood. In poor and food insecure cities, urban agriculture is often the best way to help the population heal itself with food. In Detroit, where home-based lead poisoning is common as a result of lead paint in older structures, so-called “Salsa Gardens” containing all of these vegetables are a staple in Detroit school gardens.

Fortunately, Flint, like Detroit, has a rich tradition of urban gardening and a wonderful group of gardening elders who can bring this knowledge to a new generation of people who need it more than ever before. Flint’s water is improving but its community has much healing to do. Urban agriculture can help this process—but water will continue to be a central issue. Gardens cannot be watered with lead-infused water, and, like Detroit’s farmers, Flint gardeners will have to find a way to water that does not cost too much.

Even well established programs find themselves threatened by the escalating cost of water. The Greening of Detroit has planted nearly 100,000 trees in Detroit since 1989 and boasts a 92 percent survival rate. The long-range success of Detroit’s planting efforts, in large part, is due to an innovative watering protocol which puts Detroit students to work watering trees each summer. Without the extra water provided by Green Corps members, newly planted trees would suffer and likely die over time. Students who join the Green Corps travel the city filling buckets from neighborhood hydrants and watering thousands of trees each year by hand. This work is made possible by a broad partnership led by The Greening of Detroit, which includes funders, the Detroit Public Schools Office of School Nutrition, and the City of Detroit, which traditionally has allowed the Green Corps to tap the hydrants for water without charge. In 2016, a new regional water authority took effect and the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department was placed under new leadership. The watering arrangement that The Green Corps had operated under for 17 years was cancelled.

A new agreement is in the works, but it seems clear that the water that has been keeping Detroit’s trees alive will no longer be free. In the best case scenario, this new arrangement will add expense to the program, diverting funds which had been available for youth wages to pay the City for the water needed to water its trees. In the worst case scenario, this new expense will put the cost of the program, and therefore the ability to maintain the Detroit’s trees, out of reach, leading to the demise of both The Greening of Detroit’s youth employment and its tree planting programs.

Water is a critical component of nature in cities. Its role is complex, and increasingly expensive. Water is by turns absolutely necessary, an inalienable right as some argue, and also incredibly destructive when mismanaged either in preparation or in flow. As the planet grows hotter and more crowded, fresh water in cities is likely to be one of the issues that will determine our success as a species. Michigan’s struggles, surrounded as it is by fresh water, are a cautionary tale for the world. To bring this tale to a satisfactory conclusion, Michigan and its neighbors in the Great Lakes Basin should return to the idea of Great Lakes water as a Commons, owned by no one and available to all in the region who depend on it for survival. This is the only way to ensure that this essential resource remains available to us and to the generations to come.

Rebecca Salminen Witt

Detroit

Leave a Reply