Urban livestock has long been viewed as dirty, unsafe, and decidedly un-modern by both policymakers and members of the general public. Yet, for many people living in and near the cities of developing countries, animals are a key source of food, nutrition, and livelihood. In Kenya, peri-urban chicken production has become a potentially lucrative business—especially for women—due to rapid urbanization and a booming demand for meat and animal products. Moreover, recent scientific evidence suggests that rearing chickens has benefits that could help mitigate one of the greatest health threats to developing world populations.

To illustrate how poultry raising can change lives, Public Radio International’s The World program featured a story back in 2013 that showcased an urban livestock keeper named Regina Wangari. Ms. Wangari had a thriving enterprise in the Kahawa Soweto slum of Nairobi, Kenya, where she raised chickens in small pens neatly stacked one on top of the other. From the sale of her chicks, eggs, and chickens, she earned nearly $1,000 per month—a truly phenomenal sum. Having invested some of her initial earnings in an egg incubator, she was selling more than 700 chicks per month, mainly to neighbors eager to get into the chicken production business themselves [1].

Research from the International Livestock Research Institute and others suggests that poultry production has a key role to play in boosting food security and alleviating poverty across Africa and other developing regions [2]. The Kenya Economic Report 2016 also sees it as a key livestock enterprise for attaining the UN’s Millennium Development Goal 1 of eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, as well as promoting productive employment for women and youth [3].

Small-scale chicken farming does not require huge investments in terms of space, labor, or initial inputs, which is ideal for people living in urban environments. For women, it serves as a primary, and often only, source of independent income, particularly in places where their money-generating options are limited [4]. While women are less likely then men to own land or large livestock, they typically own and manage the family chicken flock.

My own interviews with chicken producers in peri-urban areas of northern Kenya highlighted the potential benefits of poultry production, not just in Nairobi, but also in the poorer and more arid regions of the country, where urbanization is growing more rapidly. They include counties in the north and east of the country that were long ignored by government and international development investments because they were not seen as economically productive. Today, that view has changed, and the Kenyan drylands are seen as areas of significant potential growth and trade.

Kenya’s new Constitution of 2011 decentralized government budgets and decision-making authority. Known as devolution, the process has brought new money and urban growth to dryland counties such as Turkana, Isiolo, Marsabit, and Garissa.

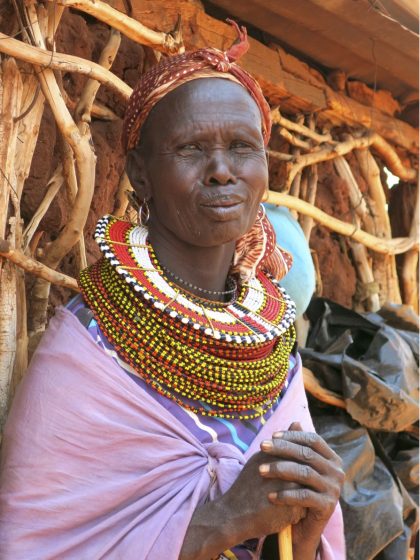

Just outside the bustling northern town of Isiolo (population 80,000), I met with members of the Aten Women’s Group, who have recently taken up chicken production. They talked about life before the formation of their group—how they scraped out what existence they could mostly by making and selling charcoal from the scarce and scruffy trees that dot the arid landscape outside of town. Finding ways to feed their families or pay for school fees and clothing was a constant challenge, as was taking care of their own needs. “We gave birth outside, under the trees,” explained one member, “and sometimes that led to problems, such as too much bleeding.”

With support from USAID’s Resilience and Economic Growth in the Arid Lands – Improving Resilience in Kenya program, the women gained access to health, financial, and training services geared at improving their livelihoods. They learned basic business skills, along with multiple aspects of small-scale chicken production—from sourcing chicks, incubation, feed, and vaccination to sales and the building of suitable chicken pens from available materials. They were taught about managing a bank account and keeping financial records. The group received funding from small revolving loans, which were used to set up each member’s chicken production.

With proceeds from their production, the women pay into a group savings account that is used for emergency expenses. At the time of my visit, the account held the equivalent of about $1,000 and was a source of great pride to the group members. “We thought only employed people could have bank accounts,” said a member.

The proximity to Isiolo town, just a few kilometers away, has provided a ready market for the women’s eggs and chickens. Isiolo is rapidly expanding due to its role as the county capital, which has brought an influx of money, construction, development, and taste for poultry. The town is benefitting also from its position along the highway from Nairobi to Ethiopia, soon to be entirely tarmacked, which is a major trade route for livestock and other goods.

Asked how the chicken production was changing their lives, the Aten Women’s Group members were all smiles. They talked about having money for their children’s schooling, clothing, and food. They bragged about being able to put better roofs on their houses and using the local health services for births and other medical needs. They pointed to their new skills and to a newfound respect garnered within their families and communities.

Traditionally, most households in dryland regions have been engaged in pastoralism, herding cattle, sheep, goats, and even camels. But competing pressures for land and water, along with stresses from climate change, population growth, urbanization, and human conflicts have compromised this way of life. Most pastoralists no longer have big enough herds to live solely off their animals.

Nowadays, the real money is in commercial livestock rearing, where owners have the resources (e.g., large herds, ties to feed lots, water sources, market access) to weather prolonged droughts and exert influence over market prices. Meanwhile, smaller herders are more likely to have to sell off their animals in times of stress, often at unsustainably low prices. Individuals may also lose their stocks of ruminants to disease, drought, and livestock raids from enemy tribes.

As former herders are becoming more sedentary and urbanized, chicken rearing is increasingly becoming an attractive alternative.

“Chicken feed, chicken vaccines, and live chicks have rapidly become our fastest growing and highest selling products,” says Dr. Diba Dida Wako, a veterinarian and businessman, who manages Sidai Africa Ltd. in northern Kenya. Sidai is a social enterprise that provides animal health products, services, and advice through franchised and branded service centers. “We had expected that most of our business would center around cattle—the animals most associated with livestock production and pastoralism. The huge demand for poultry products was a surprise,” he notes with a laugh. “So we have had to adjust quickly to this major market shift.”

Of course, poultry raising is not a complete panacea for people in the cramped conditions of urban slums or peri-urban areas. Proper air quality, ventilation, space, temperatures, feed, and vaccines are essential for good chicken health and productivity. But these are challenges in informal and poor communities, where any one of those factors may be compromised or unachievable. The results greatly increase the risks of diseases and conditions that may not only decrease productivity but also wipe out an entire flock.

Living in close proximity with chickens can also increase human health risks. Diseases, such as avian influenza, can transfer from animals to people (a process called zoonosis). Waste from the chickens and their feeds are potential environmental and health hazards if not properly managed. Waste runoff can contaminate ground water with excess nitrogen and phosphorus, or with potential pathogens, such as salmonella. In addition, the organic nitrogen from chicken manure quickly converts into ammonia, which can then be emitted into the atmosphere as a pollutant.

On the positive side, chicken manure is a good natural fertilizer. The litter and manure also can be converted into bioenergy, according to FAO, or even recycled as a component of livestock and poultry diets, when the pathogens are neutralized [5]. So, there is potential for further spin-off businesses associated with urban chicken production—not such a far-fetched concept in a country as entrepreneurial as Kenya.

Further promise comes from a report recently published in Malaria Journal, based on a study by Swedish and Ethiopian researchers. Working in Ethiopia, Rickard Ignell and his team discovered that the smell of chicken repels the Anopheles arabiensis mosquito, which is the main vector for the spread of malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa [6]. They found that certain compounds within the chicken feathers (isobutyl butyrate, naphthalene, hexadecane, and trans–limonene oxide) kept the mosquitoes at bay. As a result, suspending a chicken in a cage near where people were sleeping was enough to drive the insects away.

So, home-based chicken farming may be doubly advantageous for city dwellers in Kenya, Ethiopia, and other countries around the continent. Finding how best to reap the benefit of chicken proximity without encouraging the spread of disease seems entirely achievable. ILRI scientists have already suggested that keeping chickens in a wicker cage at a distance from the bed, instead of under it as is commonly done in cramped conditions, is a healthy alternative.

But making the most of these potential benefits requires government and program policies that support urban and peri-urban chicken production. Policies and programs that restrict small-scale urban livestock production only serve to promote evasive actions. Instead, they must spur the adoption of good practices through extension services, business training, farmer-to-farmer linkages, financing schemes, access to quality chicks, and other activities that will strengthen the potential of poultry production for reducing poverty and improving lives.

And focusing on women, who dominate small-scale poultry production, is key [7]. While men still dominate large-scale livestock production, it is clear from the stories of Ms. Wangari in Nairobi and the Aten Women’s Group in Isiolo that there is still plenty of room at the bottom of the pyramid for small-scale urban producers—and plenty of room for chickens in the city.

Valerie Gwinner

Nairobi

Notes and Further Resources

- Kelto A, Farming Livestock in African Slums, PRI’s The World, Jan 28, 2013. http://www.pri.org/stories/2013-01-28/farming-livestock-african-slums

- Sambo E, Bettridge J, Dessie T, Amare A, Habte T, Wigley P, Christleya RM. Participatory evaluation of chicken health and production constraints in Ethiopia. Prev Vet Med. 2015 Jan 1; 118(1): 117–127. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4300415/

- United Nations Millennium Development Goals. un.org/millenniumgoals/poverty.shtml

- Sambo E, Bettridge J, Dessie T, Amare A, Habte T, Wigley P, Christleya RM. Participatory evaluation of chicken health and production constraints in Ethiopia. Prev Vet Med. 2015 Jan 1; 118(1): 117–127. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4300415/

- Williams CM. Poultry waste management in developing countries. FAO Poultry Development Review. fao.org/docrep/013/al715e/al715e00.pdf

- Jaleta KT, Hill SR, Birgersson G, Tekie H, Ignell R. Chicken volatiles repel host-seeking malaria mosquitoes. Malaria Journal. 2016 Jul 21; 15:354. http://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-016-1386-3

- Ngeno V, Langat BK, Rop W, Kipsat M. J. Gender aspect in adoption of commercial poultry production among peri-urban farmers in Kericho Municipality, Kenya. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics. 2011 July; Vol. 3(7), pp. 286-301. http://www.academicjournals.org/JDAE

What this article glaringly omits is the terrible welfare conditions of chickens in such countries – there is no ‘humane’ slaughter, (which is a myth, but is even more brutal in these circumstances), and the chickens are kept cramped in cages.