about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

After many months and years of planning, and 20 years after Habitat II, Habitat III is a reality. As befits a gathering that happens only every 20 years, its goals are ambitious—there’s a lot to do. There is potential reward and risk, potential hope and disappointment built into the fiber of a convening such as Habitat III. Its grand gestures could inspire a vision that propels countless people to enact that vision on the ground in cities around the world. Or, the distance between metaphorical flourish and actionable agenda could be too great for implementation. The immense congress of urbanists, humanists, civil society, academia, people from government, practitioners—45,000 in all—might create an ambitious and specific vision for urbanization that serves humanity well. Or, such a sprawling group might file away all the sharp and controversial edges, producing a “vision” that is both bland and toothless. Bland and toothless will not serve us well, given the broad challenges to resilience, sustainability, livability, and justice around the world.

So Habitat III is a heavy lift, and the weight of the (urban) world lies across its broad shoulders. Everyone who has invested in Habitat III is to be celebrated and offered a hearty “Thank You”.

Habitat III has an outcome document. It hopes that heads of state and government commit to an urban paradigm shift for a New Urban Agenda grounded in the integrated and indivisible dimensions of sustainable development: social, economic, and environmental. This New Urban Agenda [is adopted] as a collective vision and a political commitment to promote and realize sustainable urban development, and (…) a historic opportunity to leverage the key role of cities and human settlements as drivers of sustainable development in an increasingly urbanized world.

In this roundtable, we want to focus the hope—for outcomes of Habitat III, as opposed to its outputs. Many, or even most, of the agenda’s outcomes won’t be known or evaluated for years. So, we’ve asked a group to project what they think the most important one is. As one might expect, the responses are diverse. Justice, equity, and housing are mentioned often. Better governance and increased capacity are key. Several of our contributors discuss the need for integrating the urban-rural gradient into a landscape concept that avoids false and unhelpful dichotomies.

The marriage of social, economic, and environmental is important in the Habitat III outcome document, and this is reflected in the responses here. The future of cities isn’t only about sustainability, or housing, or resilience, or indeed about any single thing. It is about finding a mix of social, economic, and ecological goals, and find a way to act on them.

Exactly how to act, and who will act, remains one of most difficult aspects of Habitat III: getting from vision to action.

about the writer

Anjali Mahendra

Dr. Anjali Mahendra is an urban planner & transport policy expert working at interface of research & practice on issues dealing with cities, transport, climate change & economic development

Anjali Mahendra

Increased authority, capacity, and resources for cities

Habitat III would be a success if it catalyzes the adoption of policies and incentives allowing city and local governments to play their critical role in implementing the New Urban Agenda, in partnership with national governments. Translating the impressive New Urban Agenda document to action on the ground requires enabling cities around the world to meet their citizens’ needs for core urban services and infrastructure. This is particularly true for rapidly urbanizing regions of Asia and Africa.

I want the Habitat III process to increase the authority, capacity, and resources for cities to become more effective partners in the development agenda.

We know that by 2050, about 3/4 of the world’s urban population will live in Asia and Africa, and 90 percent of the increase in urban population between now and then will occur in these regions. These are the regions with the largest number of low-income countries, fewest resources available to cities, fastest growing urban populations, and serious governance challenges. It is crucial to get ahead of the curve and give cities in these regions greater authority, capacity, and resources, within the larger framework of a national urbanization policy.

Ensuring this outcome requires a focus on at least three key areas:

- a national policy for urban development linked to key economic and environmental goals, aligned with the New Urban Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (or SDGs)

- access to multiple financing sources for cities and authorities to raise municipal finance in innovative ways

- increased capacity for cities to manage land and provide core services and infrastructure to all citizens

Experts tend to agree that the New Urban Agenda is a comprehensive document that identifies important areas, such as the need to manage urban expansion and consider transit-oriented development—ideas included for the first time in an internationally negotiated document. But, knowing that this Agenda is not binding on countries, certain steps are important to ensure its implementation.

National policies guiding urban development enable coordination and management of the urbanization process and exist in countries such as South Korea, Brazil, and Mexico. For lower-income, rapidly urbanizing countries in particular, a national policy framework aligned with the New Urban Agenda could not only enable implementation of the Agenda, but also the SDGs at the local level. It would allow countries to harness the urbanization process to achieve broader and more inclusive development goals.

Cities need greater authority to access national and international streams of finance, as well as to raise their own revenue in innovative ways. In 2012, more than 482 million urban residents lacked access to modern fuels and 131 million lacked access to electricity; and in 2015, 140 million urban residents did not have reliable, clean water. Significant investment is needed to address the serious gap in urban services, particularly in fast-growing, low-income cities. In other work we are doing, we show how effective management of land use and equitable access to core services such as housing, transportation, energy, water, and sanitation, can bring environmental and economic benefits to all city residents.

Finally, cities need increased capacity to plan and manage urban growth in the form of stronger institutions and technical expertise. As the numbers above show, large numbers of people in cities that are seeing rapid urban population growth are underserved by core services and infrastructure. In our research, we find that the lack of access to core urban services causes city residents to fend for themselves in inefficient and costly ways, with risks to the environment as well. This undermines urban and national sustainability goals. But in many countries, city leaders and municipal agencies lack the capacity to deal with this growing challenge.

I want the Habitat III process to instigate national governments around the world to adopt policies that increase the authority, capacity, and resources for cities to become more effective partners in the development agenda. If this outcome is achieved, we will start to see faster progress towards other important global agreements, such as the SDGs and the Paris Climate Agreement.

about the writer

Yunus Arikan

Yunus Arikan is the Head of Global Policy and Advocacy at ICLEI, actively involved in leading ICLEI´s work at the United Nations, with intergovernmental agencies and at Multilevel Environmental Agreements.

Yunus Arikan

The New Urban Agenda in the new UN

The New Urban Agenda kicks off a 2-year process under the authority of the UN Secretary General and the UN General Assembly to define its modalities of follow-up and review. This process will overlap with the expected UN-wide reforms under the new UN Secretary General—who will take the office on 1 January 2017.

The New Urban Agenda will pave the way for developing a new model of collaboration and engagement of the local and subnational governments in the UN system.

Both of these processes will be designed for and implemented in a world that is more urbanized and connected than ever before. Thus, both follow-up and review of the New Urban Agenda and the UN reform, in practice, will focus on defining a new concept for the UN system and ways for its Member States to engage with local and subnational governments, as their role in the implementation and advancement of global sustainability goals become even more crucial.

Sustainable urban development: evolution beyond the HABITAT Agenda

The period between 1972 and 1976, starting with the Stockholm Conference on Environment and ending with the Vancouver Conference on Human Settlements, was the first cycle of intergovernmental efforts that laid out the foundations for sustainability within the UN system. The second phase, from 1992 to 1996, starting with the Earth Summit in Rio and ending with HABITAT II in Istanbul, defined the basic principles of sustainable development.

During the implementation of this second phase, the scope and focus of the HABITAT Agenda was relatively narrowed down as its mission was reoriented in response to the Millennium Development Goals, which decoupled it from the rest of the sustainability agenda. The Habitat Commitment Index by the New School is recognized as one of the key indices that assesses progress in this period. Meanwhile, thousands of locally driven sustainability planning, consultation, and implementation processes have been nourished in this period, building on the spirit of Local Agenda 21, and stemming from the Earth Summit held in Rio in 1992. These ambitious and progressive actions on the ground have yielded fruits, resulting in key achievements relating to the engagement of local and subnational governments in numerous UN processes on climate change, biodiversity, and procurement in particular.

The New Urban Agenda: bringing urban development back to the sustainability agenda

In the broadest terms, HABITAT III was expected to conclude the third phase of these intergovernmental efforts, which started with Rio+20 in 2012. In fact, the HABITAT Agenda was already reflected into the universal Sustainable Development Goals adopted in 2015 through Goal 11, which focuses on making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable—goals which are almost identical to paragraph 1 of HABITAT II in 1996. However, it was not possible to enshrine a clear linkage between SDGs and HABITAT IIII until the last hours of the informal session in September. Luckily, paragraph 9 of the Quito Declaration finally foresees that the New Urban Agenda will “localize the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in an integrated manner, and contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and targets, including SDG 11”. Together with paragraphs on follow-up and review, it is now possible to confirm that the New Urban Agenda is a core element in this third phase of the sustainability agenda, which is expected to be more holistic, transparent, inclusive, and transformative.

The New Urban Agenda in the making of the new United Nations of the Urban World

Pursuant to the recognition of the enormous need, potential, and power of local and subnational governments to support national and global efforts, almost all UN agencies now have some sort of a project, programme, or initiative focusing on cities and regions. The Executive Office of the UN Secretary General is also advancing its support by expanding the Subnational Climate Action Hub, initiated at the Paris Climate Conference in December, to all SDGs and relevant stakeholders.

Therefore, the implementation of a 2-year consultation indicated in paragraphs 171 and 172 of the New Urban Agenda may easily be expanded to all members of the UN system, pursuant to the leadership of the UN Secretary General and the UN General Assembly in the process. This will include an assessment of UN-Habitat commissioned by the UN Secretary General, which will be followed by a high level meeting at the UN General Assembly in 2017, and conclude with a decision of the UN General Assembly in 2018. It is hoped that the process will have strong interactions with some other events in 2017 (such as the UN-Habitat Governing Council in April, the UNFCCC stakeholder engagement workshop in May, and the 3rd UN Environment Assembly in December) and in 2018 (the World Urban Forum in February, the IPCC cities conference in March, and a High Level Political Forum focusing on SDG 11 in July.)

It is obvious that these consultations will go hand-in-hand with the expected UN reformed agenda under the new UN Secretary General starting in 2017. In the Urban World of 2030, appropriate utilization and vertical integration of the potential, ambition, and power of the local and subnational governments is key to ensuring successful attainment of any global goals and national commitments. Thus, one of the biggest outcomes of the New Urban Agenda will, in fact, be to pave the way for developing a new model of collaboration and engagement of the local and subnational governments in the UN system. If this process delivers the necessary innovations, it will be considered the biggest legacy of HABITAT III.

about the writer

Genie Birch

Professor Genie Birch is the Lawrence C. Nussdorf Chair of Urban Research and Education, former Chair of the Board of Trustees for the Municipal Art Society of New York, and co-chair, UN-HABITAT’s World Urban Campaign.

Eugenie Birch

The recently completed draft New Urban Agenda, the Habitat III outcome document, reaffirms member states’ support of planning and managing urban spatial development and, equally importantly, providing the enabling environment (a supportive governance and means of implementation—knowledge, capacity-building and finance) in which those activities can occur. It does so in each of its parts (the “Quito Declaration,” “Quito Implementation Plan for the New Urban Agenda,” and “Follow-Up and Review”).

The prioritization of place in the New Urban Agenda is the single most tangible outcome of Habitat III.

While the New Urban Agenda pursues these priorities with simultaneous and synergistic actions, the recommendations for planning have a specificity that provides a clear roadmap for public and private decision-makers to tailor programs to their particular environments. Thus, I believe that “place matters”, as seen in the detailed articulation of the physical characteristics of a place, is the single most tangible outcome of Habitat III.

Note that the NUA assumes that urban places will have to accommodate some 2.5 billion more residents in the near future and will need to offer opportunities for efficient and agglomerative economic growth and protection of the environment overall. Further, the NUA recognizes the economic value of well-planned places—a fundamental issue related to individual and collective prosperity, i.e., the ability of property owners to increase their own assets and of cities to experience robust productivity that would reflect their overall economic health.

So, let’s take a look at the elements of the roadmap that are in the New Urban Agenda, remaining mindful that while its recommendations reflect general principles related to achieving sustainable urban development, contextualization of the recommendations will be essential. That is: “The devil is in the details”, and this is where multi-stakeholder work is going to be essential.

For overall guidance, the NUA refers to UN Habitat’s Guidelines for Urban and Territorial Planning, adopted by the Governing Council in April 2015, and which outlines roles for spheres of government: national (e.g. connect and balance the system of towns and cities); metropolitan (e.g. regional economic development, rural/urban linkages, ecosystem protection); municipal (e.g. design and protection of citywide systems of public space, capital goods investments in basic infrastructure, overall block layout, connectivity); and neighbourhood (e.g. site specific design, local urban commons).

Throughout the documents the reader will find specific recommendation that include:

- A strong call for implementing integrated, polycentric, and balanced territorial policies and plans (para 95), which entails national urban policies that frame the spatial development of a nation (para 89)

- A statement on the importance of planned urban extensions and infill development as a means of protecting natural resources and ecosystem services in the surrounding territory, as a means of supporting compact development (para 51)

- Within urban places, treatment of the key elements that make a place safe, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable

- Housing: several paragraphs call for adequate and affordable well-services dwelling units for all (paras 99, 105-108, 140)

- Transportation: several paragraphs that deal with multi-modal mobility call for efficient and equitable public transit, including instituting equitable transit oriented development (TOD) (paras 113-118, 141)

- Public space and green open space: many references to having sufficient, accessible space for recreation, infrastructure (streets, water/sewer), and social and economic uses (paras 36, 54,67,100) .

- Basic services: water and sanitation top the list (paras 34, 88, 119), but dealing with waste management is also noted to be of critical importance (para 74), as are the creation of building codes (111, 121, 124) for safety and resilience.

- Heritage: appreciation of the value of cultural heritage as contributing to the social and economic lives of the residents and to environmental preservation is clearly articulated. Of note is its appreciation of the wide variety of the sources of culture (paras 38, 45, 60, 97, 125)

A roadmap is not sufficient without the political will to use it. In the coming years, the key challenge will be to energize, inspire, and convince the member states to undertake the necessary programs—and this is where stakeholders, such as those from the General Assembly of Partners and the Global Task Force, come in. Working in a multi-stakeholder partnership model, they can have a critical role in keeping awareness of the key elements of the roadmap present in the minds of their constituents and in the everyday business of national, regional, and local government. That is, they can monitor and advocate fiercely. Further, at all stages of implementation, they can help provide the knowledge to help guide the policy choices to be made by all spheres of government. One question remains: can stakeholders meet the challenge of working for the collective interest while still safeguarding their specific group concerns?

about the writer

Jose Puppim

Jose A. Puppim de Oliveira is a faculty member at FGV (Fundação Getulio Vargas), Brazil. He is also Visiting Chair Professor at the Institute for Global Public Policy (IGPP), Fudan University, China. His experience comprises research, consultancy, and policy work in more than 20 countries in all continents.

Jose Puppim

Cities and inequities

Cities are core drivers of inequities and inequalities. Habitat III has a chance to raise this issue, creating an alliance to fight inequalities by bringing together like-minded leaders from the North and South, local and national tiers, governmental and non-governmental organizations. Leaders have the opportunity to change the game of inequality by addressing the core of it—that is, the patterns of unsustainable urbanization in the North and, more recently, in the South.

Habitat III offers a chance to show the importance of sustainable urbanization to fight inequalities within and beyond cities.

Making changes will require a different view of the role of cities and their primary long-term development objectives, shifting urban development from being based on consumption and concrete buildings to quality of life, resource conservation, and sufficiency.

There is so much said about urbanization and its economic and social achievements. “This is the century of cities”, “Cities are the drivers of the economy”, “Cities are the hubs of innovations”, and so on. However, one of the less explored aspects of rapid urbanization is its relation to rising inequalities around the world.

Although growing inequalities have gained interest in global and domestic agendas, less is said about the role of urbanization in the increase of these inequalities. This pattern not only includes inequalities within cities, which are already well studied (from the favelas of Rio and Nairobi to the American inner cities and the banlieues of Paris), but other, more subtle kinds of inequalities that have both short and long-term consequences, such as energy use, carbon emissions, and migration.

Urbanization has strong links with several kinds of inequalities and inequities. The core of this problem is the capacity of cities to concentrate and consume extraordinarily, and to expel their unwanted residues to other places, causing several consequences for some of the urban population and for populations elsewhere, particularly in rural areas.

Let me give some examples. Cities concentrate human capital. They attract youth and talent to generate economic activities, leaving rural areas relegated to the elder and less productive segments of society. Take the examples of rural areas in Japan and Spain, which are deserted of young people or are completely abandoned, generating a series of social (e.g., lack of social services), economic (e.g., drop in income) and environmental problems (e.g., uncontroilled wildfires). We witness similar phenomena in developing countries, such as China and India, where the best, brightest, and fittest go to the cities.

Another example is consumption. Cities consume the bulk of the world’s energy, water, and other natural resources, directly and indirectly; some estimate that 75 percent of energy is consumed in cities. Thus, as many countries do not have the capacity and resources to generate electricity for all their population, rural areas end up short of electricity. Electrification in many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, is less than 15 percent. Those populations are stripped of many services and economic opportunities available in cities, creating and perpetuating inequity. A similar problem happens with access to clean water, as many rural areas lack a clean water supply.

In a third example, cities in urbanizing middle-income countries tend to emit carbon per capita similarly to cities in richer countries, while some of their rural population has low or even negative per capita carbon emissions. This has implications for designing a fair global regime for ending energy poverty, tackling climate change, and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Urban-rural inequalities and inequities in the making of emissions of greenhouse gases and the impacts of climate change.

Habitat III could open up discussions on the broader implications of cities for increasing inequalities and inequities. Just emphasizing cities as engines of economic growth creates stiffer competition among cities, which leads to more consumption, higher concentration of wealth, and more pollution. These, in turn, increase inequities, which are generally felt hardest by the poorest and weakest in cities and rural areas, who have little voice and suffer from having fewer resources and opportunities.

Habitat III offers a chance to show the importance of sustainable urbanization to fight inequalities within and beyond cities. Pointing to unsustainable urbanization as the major source of inequalities will have long-term connotations for the people and for the planet. Following the advice of Mahatma Gandhi, the planet “has enough for everyone’s needs but not for everyone’s greed”; and cities are at the core of this debate.

about the writer

PK Das

P.K. Das is popularly known as an Architect-Activist. With an extremely strong emphasis on participatory planning, he hopes to integrate architecture and democracy to bring about desired social changes in the country.

PK Das

Let’s commit land for affordable housing

The single most important outcome of the Habitat III conference would be if all participating nations unequivocally agreed to commit land in their cities exclusively to construction of affordable housing (this does not come through in the draft of the “New Urban Agenda”, Habitat III’s outcome document). Thereafter, various governments would have to undertake direct responsibility for building affordable housing, rather than relying on markets for their supply.

Our collective focus has to shift to affordable housing alone, given the gravity of housing conditions in most cities.

The exclusion of more and more people from the benefits of development, particularly their access to formal and dignified housing, is squarely a failure of the current patterns of urbanization, which are steadfastly undermining the very idea of cities. Expanding cities are by no means indicators of desirable and sustainable urbanization. Achievement of higher human development standards, along with equity and justice for all, would be true indicators of successful urbanization and city-making efforts. Tragically, cities are being rapidly divided into disparate fragments of exclusive communities and marginalized populations. It is in this context that the Housing Question has to be understood and evaluated. Our failure to ensure this basic human right to a vast majority of city populations exposes our failure while challenging our collective capacity and capabilities.

The central issue in the housing question is land. Unfortunately, this statement has to be reiterated. The question that confronts us is, how do we achieve equity in land use and interweave the disparate fragments of our fast growing cities into unified landscape? We hope these questions are dealt with bluntly and squarely, and will lead to tangible outcome at the Habitat conference.

We hope the final declarations will overcome the overarching generalizations in the draft documents and will outline more specifically much-needed interventions for the equitable distribution of land and an increased role of governments in building affordable housing and amenities for all. However, the more daunting task will be to incorporate and reflect multitudes of local needs and demands into a set of common principles and action plans for the achievement of these objectives. While respective governments may put local plans together, it was agreed that one outcome of the Quito conference would be to collectively review, intermittently assess, and agree on individual cities’ and nations’ action plans for successful implementation of the global objectives.

Equity in land use

We have to bring land back to center stage in our discussion; over the years, as countries have committed to neoliberal globalization, the question of land has been pushed to the backstage. Substantial public land has been gifted away by governments and/or captured and colonized by private developers, who have been mandated to carry out development works, including public housing. Therefore, our questions related to just utilization of land are not being raised, as they would impinge on the freedom of free market forces. Such a model of development has not worked in favor of the public interest, nor has it contributed to the public good.

In many instances, without pledging land, governments have been beating around the bush, negotiating deals with private landowners and developers, who seeking concessions by dedicating a percentage of the built-up area in their high-cost projects towards affordable housing. Such a begging-bowl approach is only scratching the surface of this gigantic crisis that is crippling our cities and causing serious social unrest. On a related note, we also hope the outcome at the Quito conference formally calls off our increased dependency on markets for the promotion of affordable housing.

This exercise of allocating land for housing must not infringe upon the natural areas and ecologically sensitive zones and open spaces provision. Can the Habitat-III firmly resolve that all nations who are signatories commit to this significant step in the interest of checking climate change impacts?

But in many cities, large tracts of land are colonized and/ or occupied and contain very little vacant land. Poor and lower- middle class people, have managed to find roofs over their heads by living in slums and other informal settlements, often in very poor conditions. Slums have proliferated due to the non-unavailability of affordable housing. Can the present land occupation pattern— which is consistent with demand, although it is termed illegal or informal—, be accepted and formalized by incorporating these settlements into the development plan of cities? Reserving slum land in the development plans of cities would be one way of gaining land for affordable housing.

Focus on affordable housing

Currently, the Habitat declaration merely specifies the need for governments to allocate land for housing. This is too general; it is rather weak as a proposition, given the current situation of land in cities. We know that land earmarked for housing has been taken over and exploited almost entirely for exclusive upper class housing, high-cost amenities, and commercial development. Therefore, land has to be more specifically reserved for affordable housing. It is time that we collectively resolve under the UN Habitat III banner that “Housing” be re-addressed, or rephrased as “Affordable Housing” in all our discussions and documents. Our collective focus has to shift to affordable housing alone, given the gravity of housing conditions in most cities. Let the rich and those who can afford to buy or rent on the open market continue to rely on private builders and developers to fulfill their desires. We need not invest our collective time and resources to facilitate them.

We hope the UN Habitat III conference resolves that governments of all participating nations agree to commit adequate land to and will actively undertake the development of affordable housing and amenities, for the achievement of just, equal, and sustainable cities.

about the writer

David Simon

David Simon is Professor of Development Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London and until December 2019 was also Director of Mistra Urban Futures, an international research centre on sustainable cities based at Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

David Simon

Aside from the organizational deficiencies of the Habitat III Secretariat, which have left many organisations, including strategic partners of UN-HABITAT, scrabbling around at the last minute to find alternative venues and formats for planned side and networking events in a way that might make navigating the site and programme difficult, this summit has profound symbolic importance. This significance lies in the unprecedented global attention to and recognition of the key role of urban areas and other sub-national entities in the meeting, the challenges of climate/environmental change, and promoting transitions to sustainable development.

The most important outcome from Habitat III would be a commitment to the rapid establishment of clear and specific implementation and verification mechanisms for the New Urban Agenda.

The New Urban Agenda (or NUA), to be adopted by world leaders as the centerpiece of the summit, has been forged through long and wide-ranging participatory processes involving government negotiators and diverse stakeholder groups around the world. The extent of engagement by such non-state actors in UN parlance, first experienced in the formulation of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (or SDGs) adopted by the UN General Assembly last year, is itself evidence of belated and essential recognition that national governments can no longer address today’s societal challenges alone.

Not only does the NUA provide a progressive and holistic approach to sustainable urban development, it also formally recognizes the essential role of sub-national entities (i.e., urban local and regional authorities) in promoting such urban sustainability transitions. Curiously, despite such bodies constituting fundamental parts of the state sector, the UN still defines them as non-state entities. Accordingly, formal recognition in the NUA required a protracted struggle against opposition from various national government negotiators seeking to preserve an outdated central government monopoly of power in the UN system.

The NUA also recognises the importance of engaging all stakeholder groups, including academia, and urges the formation of multi-stakeholder partnerships to promote urban sustainability. It stops short, however, of providing any specific mechanism to establish a science-policy interface through which to mobilise research and scientific evidence as the basis for implementing evidence-led policy. The previously proposed Multi-Stakeholder Platform—which grouped academia together with civil society—was cut from the semi-final draft during the Surabaya negotiations in July. This illustrates how forging the intergovernmental consensus required in order to agree and adopt the NUA in Quito has produced a document that will serve that purpose very well, but which lacks teeth or any monitoring and evaluation stipulations beyond very general means of implementation and four-yearly progress reports to the UN.

Similarly, attempts to establish a formal link between the NUA and the broader 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the associated set of 17 SDGs could not gain the required support for inclusion. Hence, the NUA merely acknowledges these and other relevant documents such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction in the Introduction, but the opportunity to use SDG 11 and the relevant elements of other goals as a monitoring and evaluation framework was lost.

Hence, to my mind, the most important outcome from Habitat III would be a commitment to the rapid establishment of clear and specific implementation and verification mechanisms. Perhaps the SDGs could still be mobilised to this end outside of the NUA itself, in order to avoid having to establish a wholly different set of metrics.

Another key aspect will be to engage the urban science research community (which is diverse and by no means restricted to universities and higher education institutions) and other important holders of local urban knowledge (including indigenous knowledges). These could be constituted (sub-)regionally, on the basis of agro-ecological or physiographic zone, or nationally to promote the availability of appropriate evidence alongside the strengthening of multiscalar governance between urban, regional, and national government bodies within each country. Such engagement processes should be as lean and bureaucracy-light as possible.

That all these issues remain to be addressed outside of the NUA itself will add to the overall administrative and negotiation burden after the conference, and incur delays, as will the commitment to commissioning an independent external review of UN-Habitat contained in the final NUA text. While perhaps politically expedient, this invokes several large hostages to fortune and risks the loss of momentum so carefully built up through the SDG and NUA negotiation processes. To lose this historical urban moment would be a tragedy, particularly after the vast energy expended to date in pursuit of greater urban sustainability.

about the writer

Pengfei XIE

Pengfei is China Program Director of RAP (Regulatory Assistance Project). RAP is a US based non government organization dedicated to accelerating the transition to a clean, reliable and efficient energy future.

Pengfei XIE

The UN’s Habitat III conference is fast approaching. As a person working in the international NGO community, I think the most important possible outcome of this great event would be the strengthening of international exchange and cooperation on human settlement development over the next few years.

To achieve sustainable urbanization post-Habitat III, national governments should build capacity, mechanisms, and platforms.

The reasons that this outcome is most important to me are twofold. First, the need to jointly fight against climate change. The threat of climate change to the entire human community and the human settlement has reached universal consensus. No country can stay safe alone, or be spared by climate change. We need to join hands and work together to meet this challenge by strengthening cooperation in the fields of technology, information, capital, talent, and so on. The goal of controlling global temperature rise won’t be possible without this joint effort. Second, we need healthy development of urbanization. Urbanization has become an important engine for promoting world economic development. Urbanization is also one of the key themes of the “New Urban Agenda”, which is a programmatic document of Habitat III. The next 20 years is going to be a critical period of urbanization, especially for developing countries. We are in urgent need of experiences and lessons from other countries to use as references, via international exchange and cooperation.

In order to achieve this outcome, it is important for country governments to try to achieve the following points:

1) Capacity building. Provide training for policy makers and relevant stakeholders, so that they realize the importance of international cooperation, have the necessary knowledge of it to be able to practice it, and, ultimately, to be good at implementing it. For example, the National Academy for Mayors of China undertakes the task of training the nation’s Mayors. An important part of the training is to teach the Mayors how to conduct international exchange and cooperation between cities

2) Mechanism building. Establish a fair, mutually beneficial, and win-win international cooperation mechanism that is constructed, shared, and co-ruled by countries of the world. For example, the New Urban Agenda issued by the United Nations is actually a new international cooperation mechanism of this kind

3) Platform building. Create broad international cooperation platforms among country governments, non-governmental organizations, and other relevant stakeholders. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, initiated by China and participated in by various country governments, is one example of an international platform working to promote infrastructure construction that can benefit the development of human settlement.

about the writer

Lorena Zárate

Lorena Zárate is co-coordinator of the Global Platform for the Right to the City and former president of the Habitat International Coaltion.

Lorena Zárate

Habitat III and the Right to the City—a commitment to a paradigm change?

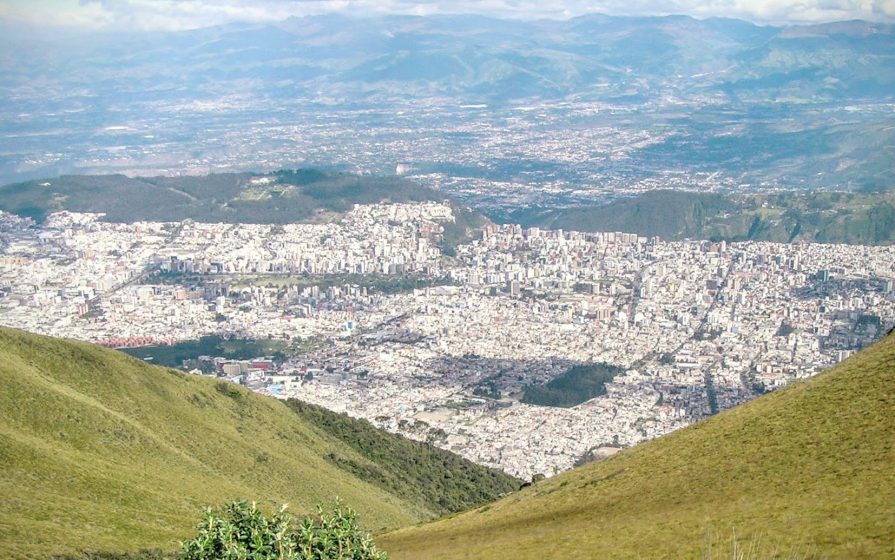

After almost three years, including the last four months of intense and not always easy negotiations, the text of the so-called New Urban Agenda (or NUA) is finally ready for approval during the UN’s third Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development in Quito, Ecuador (Habitat III). Some voices are quite satisfied with both the process and the outcome so far, while others are not. Some voices are optimistic about the implementation and follow-up measures that have been established; others are not. What is certainly clear is that the general balance cannot be framed in a categorical, “all or nothing” formulation.

The inclusion of the right to the city framework in the New Urban Agenda is the most important outcome of Habitat III.

Thorough the process, several civil society organizations, including Habitat International Coalition (or HIC) and the Global Platform for the Right to the City (or GPR2C), in partnership with international networks of local governments, have participated at several of the preparatory steps, such as the regional and thematic official meetings, multiple editions of the Urban Thinkers Campuses and the General Assembly of Partners. At the same time, our members were engaged in the Policy Units responsible for drafting the substantive inputs for the New Urban Agenda’s first draft (May 2016), and we collectively reviewed and provided feedback on many of the subsequent versions as well as the Issue Papers released since May 2015.

As an international network which has the privilege, but also the huge responsibility, to have actively participated in the two previous conferences (Habitat I in Vancouver, 1976, and Habitat II in Istanbul, 1996), HIC maintained a positive yet critical voice, making public its concerns and proposals since the beginning of the process, which have been united around three large axes: a) the call for an holistic and integrated territorial approach to human settlements, evaluating the implementation of the commitments assumed by different actors as part of the Habitat Agenda (1996); b) the responsibility to mainstreaming human rights in public policy, according to international law, and taking into account the achievements—but also the growing challenges—during the last 20 years; and, c) the strong demand for a wide and substantial participation of non-State actors in the debates and decision-making processes, giving particular relevance to the communities, organizations, and individuals traditionally marginalized and excluded.

In that context, as part of the GPR2C, we strongly campaigned for over a year for the explicit inclusion of the right to the city as the cornerstone of the NUA. Thanks to international mobilization and tireless advocacy activities at multiple levels, the definition of the right to the city and many of its main principles and contents are now part of the “shared vision” in the Quito Declaration (paragraphs 11-13) to which the world leaders will be subscribing, making this the first time that this concept is included in an international agenda signed by the national governments at the UN level.

The synthetic definition refers to the “equal use and enjoyment of cities and human settlements, seeking to promote inclusivity and ensure that all inhabitants, of present and future generations, without discrimination of any kind, are able to inhabit and produce just, safe, healthy, accessible, affordable, resilient and sustainable cities and human settlements, to foster prosperity and quality of life for all”. The authors of the document also recognize “the efforts of some national and local governments to enshrine this vision, referred to as right to the city, in their legislations, political declarations and charters”.

Among the key components, it is worth mentioning:

- The respect and guarantee of all human rights and gender equality for all;

- The social function of land, the public control of gentrification and speculation processes, and the capture and distribution of land value increments generated by urban development;

- The promotion and support of a broad range of housing options and security of tenure arrangements, including the social production of habitat and rental, collective, and cooperative models;

- The prevention of forced evictions and displacements, as well as tackling homelessness;

- The recognition of the contributions from the informal sector and the social and solidarity economy to the urban economy as a whole;

- The commitment to sustainable and responsible management of natural, heritage, and cultural goods; and,

- The integrated vision of the territory beyond the urban-rural divide, understanding regional interactions and responsibilities beyond administrative boundaries.

Although all the references to “democracy” have been removed from the text after the first draft (we want them back!), there are several mentions of the promotion of substantial citizens’ and social participation in the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of public policies and national and local budgets. The document also mentions the need for greater inter-institutional coordination inside and between the different government sectors, as well as the recognition of the key role of subnational and local governments in advancing towards more inclusive, participatory, and sustainable cities.

We are not naïve and we know that having those values and commitments on paper will not be enough. We also know that many of those same values and commitments were already enshrined in the Habitat Agenda (1996) and even before, as part of the Vancouver Declaration (1976).

A real change of paradigm will necessarily include a serious questioning of the current production, distribution, and consumption patterns; of goods and services in general; and of human settlements in particular. The mantra of “sustained economic growth”, repeatedly mentioned in the NUA is clearly not compatible with social justice and the planetary boundaries. Maybe a concrete example will help to illustrate this principle: the policies of building and selling houses do not necessarily comply with the right to adequate housing; on the contrary, as the 2008 financial crisis showed, patterns related to the housing market can result in a massive social, economic, and environmental disaster.

The growing inequality, tensions, and conflicts in all regions of the world—with their spatial manifestation in terms of territorial segregation—feed the exclusion and poverty circle, as well as the limitations and vulnerability of the limited representative democratic systems current in place; these are clear wake-up calls that cannot be ignored any longer.

We believe that the right to the city, as a political and programmatic agenda, offers concrete instruments to reshape human settlements as common goods and collective creations. Moving towards the implementation of this paradigm of cities and territories as rights, and not as commodities, will require fundamental changes in the conceptions, knowledge, attitudes and practices of a wide range of actors and institutions at multiple levels. Are you ready to be part of that?

about the writer

Huda Shaka

Huda’s experience and training combine urban planning, sustainable development and public health. She is a chartered town planner (MRTPI) and a chartered environmentalist (CEnv) with over 15 years’ experience focused on visionary master plans and city plans across the Arabian Gulf. She is passionate about influencing Arab cities towards sustainable development.

Huda Shaka

Time to address inequality

A clear and concerted focus on reducing inequalities within cities would be the most important outcome of Habitat III. Over the past twenty years we, the global community, have turned our attention to addressing challenges of poverty, environmental degradation, and resource consumption. What we seem to have largely neglected is the growing social and economic inequalities within our cities and societies. Habitat III, with its vision of promoting inclusive cities, is the perfect opportunity to thrust this issue into the spotlight.

Habitat III could forge the way towards a more meaningful understanding of and action against inequality at the individual city and settlement scale.

While we have not completely addressed the challenges of poverty or climate change yet, our performance is moving in the right direction on these fronts. Last year saw the number of people living in extreme poverty fall to below ten percent (still too high of course), and the decoupling of global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions from growth. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of inequality. Far from tackling it, we are still figuring out how to best measure and monitor it. In the G20 summit last month, there was a call to pay greater attention to global inequality, a metric we have only recently been able to calculate. Habitat III could forge the way towards a more meaningful understanding of and action against inequality and its impacts at the other extreme: at the individual city and settlement scale.

As a built environment professional working for a large multinational company, I have recently come to realise how little our industry understands the issues related to inequality. This is despite our work often having a direct and sometimes profound impact on these issues. Whether it is new master plans, cultural facilities, or transport corridors, such projects can either improve or worsen inequality in a society through the opportunities provided for access to employment, amenities, or housing, for example. Yet, project teams are rarely aware of such implications.

What will it take to get to a point where local economic and social inequality is adequately addressed? First, we will need an open and honest discussion on the state of inequality in our cities and its impacts. This will likely mean investigating ways of measuring and reporting inequality such that it becomes relevant and meaningful to multiple audiences: policymakers, developers, residents…etc. The discussion will also need to include a deeper understanding of the global and local policies and paradigms which have led to the current situation.

Academics and professionals who are already convinced of the need for action will have to articulate their arguments in the form of plausible solutions and strategies. These will vary from city to city, even from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, depending on the type and extent of inequality. Solutions will likely include measures at various levels, from global trade agreements and national economic policies to local plans and development controls. If we have learnt anything from the climate change movement, it is that we cannot afford to wait until a majority is convinced of the scale and importance of the challenge in order to begin addressing it. In addition, people respond far better to solutions than to alarms.

Going back to built environment professionals, we will need to train these professionals to understand and address inequality challenges. Consider that 10 years ago, only a minority of professionals understood sustainability appraisals, and it was perfectly acceptable to have a portfolio of one or two token “sustainable projects” in a portfolio of hundreds of “business-as-usual” projects. There was still much discussion about how to define and measure “sustainability” and how to convince authorities, clients, and stakeholders of its value. I may be overly optimistic, but I think that we are in a different place now: one where environmental sustainability is often the starting point and not the long-term aspiration. The same could and should happen for inequality.

Habitat III could be the beginning of a paradigm shift that will mean, 10 years from now, we are able to better understand and address inequality in our cities. A new generation of built environment professionals will consider shaping an equal and inclusive world to be their responsibility, whether they are private consultants, public officials, or members of civil society. Inequality, just like extreme poverty and greenhouse emissions, will have turned a corner and begun its decline.

about the writer

William Dunbar

William Dunbar is Communications Coordinator for the International Satoyama Initiative project at the United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS) in Tokyo, Japan.

William Dunbar

A new urban landscape approach

HABITAT III is the first major conference of its kind since the establishment of the Post-2015 Development Agenda, so one of its major roles must be to guide the urban development agenda into line with the priorities of the new overall development agenda. Reconciling these two agendas, so that those of us working in urban issues and those of us working in other conservation fields are not working at cross purposes, will be key to achieving both the goals of the draft New Urban Agenda to be adopted in Quito and the Sustainable Development Goals (or SDGs) related to urban issues.

Habitat III should cultivate landscape approaches to bring the urban agenda in line with conservation and post-2015 development goals.

So, what aspects of the development and conservation agendas need particular attention in the coming urban agenda? I’m sure each of the respondents to this roundtable will have specific points they would like to see included; my own would be the concept of the “landscape approach”. Landscape approaches have gotten a lot of attention in recent years in both conservation and development fields as a way of reconciling the seemingly competing priorities of each.

“Landscape approach”, in the sense that I am using it here, refers to the management—both conservation and use—of resources at the landscape scale. In many cases, management approaches have been based on one or more sectors, such as manufacturing or tourism, which can result in short-sighted management, inequalities, and perverse incentives—and, therefore, unsustainable use of resources. Other approaches, especially where public policy is heavily involved, are often based on administrative boundaries that have become out of date in terms of how and where people actually live and work, and, therefore, how and where resources are located, produced, and consumed. Landscape approaches, such as those promoted through the Satoyama Initiative—my main area of work here at UNU-IAS—attempt to take a holistic view of the landscape, integrating the interests of all sectors, administrative bodies, producers, consumers, and other stakeholders as much as possible. For this purpose, the “landscape” is defined as a logical unit constituting the area in which resources are used and managed by a local community or communities, for example. This could be a watershed, an administrative boundary, or something else, depending on the delimiting barriers and internal mechanisms for resource management.

The draft New Urban Agenda only contains the word “landscape” two times, but both serve to highlight ways in which landscape approaches can apply to urban issues. The first mention of landscapes is about the creation and maintenance of networks of public spaces in order to promote “attractive and livable cities and human settlements and urban landscapes, prioritizing the conservation of endemic species” (this is a nice little shout-out to “the nature of cities”, too). This mention of “urban landscapes” points to an urban area constituting a “landscape”, or collection of landscapes, in itself. In this sense, a landscape approach to urban areas would mean planning and policymaking that account for the interests of all stakeholders in this landscape. This would avoid problems related to the narrow interests of certain sectors, or the particular concerns of people who happen to live within certain administrative boundaries, potentially reducing inequalities and contributing to more fulfilled lifestyles for all.

The second mention of “landscapes” in the New Urban Agenda document is about safeguarding “a diverse range of tangible and intangible cultural heritage and landscapes”, to “protect them from potential disruptive impacts of urban development”. This hints at another kind of urban landscape approach, taking a wider view of the larger biocultural landscape, with urban areas included as just one landscape element, and the need for better integration of cities into the landscape. Cities naturally depend on the surrounding landscape for provision of a wide variety of resources and ecosystem services; likewise, rural and peri-urban areas depend on the city as a market for products and as a provider of services only found in urban areas. Despite these symbiotic relationships, planning and policy too often seem to pit urban and non-urban against each other so they end up competing for resources and other benefits. A landscape approach that considers the urban area as a vital part of the wider landscape can help to overcome this tension.

That said, the solution is not necessarily that the “Quito Declaration” and “Quito Implementation Plan” need to contain the word “landscape” more often, but rather that landscape approaches and a holistic perspective on the wider landscape should be adopted as part of the new urban agenda. If this is an outcome of HABITAT III, it will not only benefit urban planning and policymaking, but also help to bring the urban agenda in line with conservation and with the Post-2015 Development Agenda.

about the writer

Bharat Dahiya

An award-winning Urbanist, Bharat combines research, policy analysis, and development practice aimed at examining and tackling socio-economic, environmental and governance issues in the global urban context.

Bharat Dahiya

Renaissance of urban and territorial planning

Habitat III, its attendant global charter—the New Urban Agenda—and the concomitant commitment of the United Nations’ member states to it potentially act as a collective beacon for the renaissance of urban and territorial planning in the 21st century. The sine qua non for such a renaissance will be the long-term transformation of urban and territorial planning as an effective tool for sustainable urban and territorial development and management.

The renaissance of urban and territorial planning is long due for a number of interrelated reasons.

The renaissance of urban and territorial planning is long due for a number of interrelated reasons. First is the ever-increasing complexity of social, economic, and environmental challenges in the Anthropocene—reflected as they are in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and the COP21 Paris Agreement, as well as the need to address them in an integrated manner. Second is the need to manage and accommodate the fast pace of urbanization in developing regions such as Africa and Asia; in Asia alone, over 40 million new inhabitants are added to cities and towns every year. Third is the unprecedented set of spatio-demographic challenges in cities around the world, including the development of mega-urban regions, the phenomenon of urban shrinkage, and cross-border cities—to name just a few. Fourth is the importance of sound public policy and decision-making that involves various stakeholders, whether they are social (gender, youth, aged, or differently-abled), environmental (indigenous groups, environmental activists, advocates of ecosystem-based approaches, and those who address biodiversity, natural disasters, climate change, and the like), financial (people-public-private-partnerships), research (academic and research institutions, and think tanks), and media (print, online, radio, television, and social media) groups. The fifth factor is the substantive and technical progress urgently required for equipping urban and territorial planning in order to balance short-term needs with long-term desired outcomes in sustainable urban and regional development.

Whilst the renaissance of urban and territorial planning is urgent and (some would say, absolutely) necessary, it will not materialize easily. To make it happen will require administrative, institutional, procedural (also, perhaps, legal), and technological transformation as well as scientific (including applied and action) research on six interconnected fronts.

First, inter-agency and intra-agency administrative separatism will have to be reduced, if not completely eliminated. Silo-based administrative processes (e.g. processes narrowly limited within a specific discipline) have done enough harm to sound urban and territorial planning, all of which has resulted in haphazard development. Silos will have to be broken down, or “silo-effect” will have to be reduced to minimum, in order to put in practice the idea of sustainable urban territorial development.

Second, vertical institutional integration will be essential for opening up the compulsory legal and/or procedural space for (more) efficiently integrated urban and territorial planning. This will require delegation of powers to the various tiers of government—including sub-national, district, city-level, and sub-city-level authorities, which will be necessary to avoid bureaucratic quagmires and issues that have plagued multi-level governance.

Third, horizontal inter-jurisdictional coordination will be a prerequisite for the success of urban and territorial planning, especially with regard to city-regional infrastructure, urban-rural linkages, natural resources and environmental management, ecological restoration, biodiversity conservation, and urban-regional integration. This will be particularly important in the case of city-regions, mega-urban regions, urban corridors, and cross-border urban regions. Such coordination will be particularly important for addressing inter-jurisdictional fiscal disparities that hold the implementation of innovative and sustainable solutions.

Next, there is an urgent need to develop integrated approaches to address social, economic and environmental challenges in the urban and territorial context. The on-going work on “co-benefits” of developmental activities is making progress in this direction. More efforts need to be made on this front to conceptualise, develop, and implement integrated approaches that could feed into and bolster the revamping of urban and territorial planning.

Fifth, an increasing use of smart city approaches will feature in the future of urban and territorial planning. Smart city approaches will range from (i) the more sophisticated ones, for instance, such as “Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition” (or SCADA), to (ii) smart city systems, which include smart people, smart city economies, smart mobility, smart environments, smart living, and smart governance, and (iii) smart analytical and decision-support systems, such as for (a) collection, collation, compilation, analysis, and visualization of data, (b) development, analysis, and comparison of planning scenarios, (c) supporting decision-making process(es), and (iv) monitoring and evaluation, and facilitating feedback loops.

Finally, an ever-expanding scientific knowledge will act as a kingpin in the revitalization of urban and territorial planning. Future scientific knowledge will need to take into account the lessons learnt from (i) the worldwide experience in “town and country planning” practised since the advent of the industrial revolution, (ii) the implementation of urban and regional planning within various countries, (iii) the practice of metropolitan and city-regional planning, and (iv) the development plans and programs for small- and medium-sized cities. The ever-expanding scientific knowledge will combine these lessons learnt with (i) local social, cultural, and ecological wisdom; (ii) traditional knowledge on human, social, and environmental well-being; (iii) indigenous knowledge; and (iv) local developmental experience, both good and bad.

All of these factors, as well as the challenges and opportunities yet unforeseen, and inventions and technological developments yet to be made, will act as guiding lights and building blocks for the renaissance of urban and territorial planning in the 21st century.

about the writer

Maruxa Cardama

Communitas Co-founder & Coordinator. Sustainable Development practitioner promoting socio-environmental justice & intergenerational solidarity for equitable communities

Maruxa Cardama

Balanced sustainable and integrated urban and territorial development: Key pillar for implementing the urban paradigm shift of the New Urban Agenda

When TNOC asked me what I thought was the single most important outcome of Habitat III, I instantly thought that reducing the competing forces and political factors that coexist in any intergovernmental process to one aspect was no straightforward task. One could even ponder if such reduction is convenient. Intergovernmental processes marked by 20-year cycles—such as the Habitat ones are—set global agendas that are the complex result of multilateral and geopolitical contexts.

Habitat III’s articulated aim to end the dichotomy between urban and rural areas is its most important vision.

Judging by the negotiation complexities the Habitat III intergovernmental process experienced in 2016, cynical souls could argue that getting to Quito with an outcome document ready for adoption by heads of state and government constitutes the single most important outcome of an intergovernmental process that, at moments, required much more soul-searching than what its “post-2015 context” had augured.

2014 and 2015 were prolific for multilateralism, with the international community adopting several global agenda-setting frameworks: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including the Sustainable Development Goals (or SDGs), the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on Financing for Development, the Paris Climate Action Agreement, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, the Vienna Programme of Action for Landlocked Developing Countries for 2014–2024, the Small Island Developing States Accelerated Modalities of Action (or SAMOA) Pathway. Could the international community in 2016—in a post-2015 multilateral context—give birth to yet another “paradigm-shift-pursuing” global framework? In the outcome document of the Habitat III Conference, heads of state and government commit to an urban paradigm shift for a New Urban Agenda NUA (Para 5*) grounded in the integrated and indivisible dimensions of sustainable development: social, economic, and environmental (Para 24). This New Urban Agenda (is adopted) as a collective vision and a political commitment to promote and realize sustainable urban development, and (…) a historic opportunity to leverage the key role of cities and human settlements as drivers of sustainable development in an increasingly urbanized world (Para 22).

Whether in 2016—in the post-2015 multilateral context—the international community needed yet another long list of “paradigm-shift commitments” narrated primarily using previously agreed upon, multilateral language; or whether, alternatively, these noble aspirations begged for specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, and time-based implementation plans is another question. In any case, the recognition of the potential contributions of urbanization to the achievement of transformative and sustainable development (Para 4) delves deeper into the historic inclusion of SDG #11, “to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable” in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. We should warmly applaud this outcome and commend all the stakeholders who have made it possible.

After this very long introductory disclaimer and pushing myself to identify the single most important outcome of Habitat III from a technical point of view, I would like to highlight the vision for cities and human settlements that fulfill their territorial functions across administrative boundaries, and act as hubs and drivers for balanced sustainable and integrated urban and territorial development at all levels, contained in Paragraph 13.e of the Habitat III outcome document.

Urbanization and demographic growth have increasingly linked cities with their peri-urban and rural areas spatially as well as functionally, through interdependent economic dynamics, social links, and environmental synergies that overcome traditional administrative boundaries. Examples of systems for which an approach of complementary functions and flows across urban and rural spaces is needed include: supply and distribution chains of commodities and services systems (raw materials; manufactured goods; basic services such as water and electricity; financial services such as financing and insurance; or ecosystem services such as water production, air quality control, energy generation, etc.); social protection systems, including health, education, diets and nutrition; transport systems, including the infrastructure for short and long chains; food production systems, including linking urban, peri-urban and rural production; land tenure systems, including formal legal and customary tenure systems; market systems that connect producers to consumers through formal and informal channels; disaster risk reduction and risk management systems, and governance and decision-making systems.

The notion of balanced sustainable and integrated urban and territorial development can contribute greatly to the objective of equitably distributing, across the wider urban-rural continuum, the gains brought by the process of sustainable urbanization. This notion is important in achieving inclusive, climate-friendly, environmentally friendly, resource-saving, and resilient development that addresses the needs and demands of both urban and rural areas. It also promotes integrated planning instruments, cross-sectorial solutions, and systems thinking in areas such as water, energy, and food security, as well the transport and waste sectors. This concept also encourages urban density and mixed land use and contributes to securing public and green spaces, as well as to preserving biodiversity. It promotes comprehensive risk analyses as a generalized starting point for resilient urban development, as well as requiring land use planning and spatial strategies that address flows across urban and rural landscapes. Accordingly, governance and decision-making systems have to be aligned vertically and coordinated horizontally, involving actors from different levels of government—national, regional, local and municipal—and different sectors—local communities, civil society, business, science and academia, philanthropies—to reduce conflicts around the use of limited resources and facilitate the balancing of interests. All in all, balanced sustainable and integrated urban and territorial development is a departure from myopic sectoral and urban-only approaches to holistic, multi-disciplinary, multi-sector, and multi-stakeholder approaches at the city-region scale.

The Habitat III vision for human settlements that fulfill their territorial functions across administrative boundaries, and act as hubs and drivers for balanced sustainable and integrated urban and territorial development at all levels, represents a robust opportunity for governments at all levels, the UN system, practitioners, scholars, civil society, and all relevant stakeholders to harness this reinvigorated will of the international community to depart for once and for good from a perspective of political, social, and geographical dichotomy between urban and rural areas.

* The paragraphs referred to are numbered as per the Draft Habitat III outcome document for adoption in Quito in October 2016, dated September 10, 2016.

about the writer

David Dodman

David Dodman is the Director of the Human Settlements Group at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

about the writer

David Satterthwaite

David Satterthwaite is a senior fellow at IIED and visiting professor at the Development Planning Unit, University College London.

David Dodman and David Satterthwaite

The most significant global goals for the coming decades can only be achieved through major changes in the way that cities (and their governments) function. Reaching the Sustainable Development Goals (or SDGs) and meeting the commitments of the Paris Agreement on climate change will require new approaches to urban governance, greater technical and financial capacity for local authorities, and a stronger recognition of the role for local civil society both in implementing activities and in holding governments to account. Cities around the world need to be at the forefront of combining high quality living conditions, resilience to climate change, disaster risk reduction, and contributions to mitigation / low carbon development.

For the New Urban Agenda to achieve meaningful outcomes, it needs the right ingredients, political astuteness, and appropriate data.

The New Urban Agenda does not need to develop a comprehensive list of goals and commitments—this already exists in the SDGs and in the Paris Agreement. The single most important outcome from the Habitat III conference in Quito should be a recognition of the (mostly local) actions that need to be taken to achieve these goals, and a commitment by national and local governments to work in meaningful partnership with civil society groups to implement them.

What will determine the significance of this new urban agenda is its relevance to urban governments and urban dwellers, especially those whose needs are not currently met. This means that it has to be clear and relevant to the billion or so people living in poor-quality housing (mostly in informal settlements) with inadequate provision for basic services. It needs to be relevant to mayors, as well as to other urban politicians, civil servants, and other civil society groups. And what it recommends has to be within their capacities. It will have to go far beyond the SDGs, which are full of goals and targets (i.e., what has to be done), but which are very weak on how, by whom, and with what support those goals and targets should be achieved. The UN member states participating in Habitat III will have to focus on building or strengthening the institutional, governance, and financial frameworks.

There are lessons that can be learnt from “new urban agendas” of the past. Several of these, including the Healthy Cities movement, Local Agenda 21, participatory budgeting, Making Cities Resilient, and the Carbonn Climate Registry, have focused on urban areas. They included clear, simple, and relevant guidelines that got buy-in around the world. Their success was due in part to their encouragement of local actions that were relevant to local governments and supported by many urban residents. Even more significantly, the presence of a growing number of federations of slum/shack dwellers has changed the way in which urban development takes place. Such organizations are now present in more than 30 countries, where they build or improve housing, undertake surveys of informal settlements, and provide sanitation—and do this through working with local government (which allows a much larger scale of impact). This type of relationship between representative organizations of the urban poor and elected local government representatives can be genuinely transformative.

For the New Urban Agenda to achieve meaningful outcomes, it needs:

- The right ingredients: a vision that ties prosperity with inclusion, which links organized low-income groups with others who benefit from public goods and services, and which addresses both environmental sustainability and resilience.

- Political astuteness: removing discriminatory exclusion, ensuring that prevailing institutions support the Agenda, and ensuring that human rights are fully met.

- Appropriate data: indicators to monitor and report progress, that are sufficiently geographically disaggregated to be relevant for local governments local civil society and that record meaningful information about issues shaping the lives of urban residents.

In summary, then, for the New Urban Agenda to achieve tangible outcomes, it needs to be concise and clear, to focus on the implementation of goals, and to recognise the importance both of competent and effective urban governments and of getting the buy-in of urban residents, including those living in informal settlements. If this can be achieved, then there is a genuine chance for transformative change for cities and citizens in the 21st century.

For further information, see “A New Urban Agenda?” (Environment and Urbanization Brief 33, pubs.iied.org/10800IIED).

about the writer

Nelson Saule

Nelson Saule is an Urban Law Professor of the Post Graduate Program in Law from University Catholic of São Paulo and Coordinator of the Right to the City Area in Polis Institute of Studies

Nelson Saule

The Right to the City as the center of the New Urban Agenda

The current urban development model has failed to give the majority of the inhabitants of cities a dignified urban life. This model has promoted the commodification of the city that favors financial groups and investors to the detriment of the interests and needs of the majority of the urban population. The pattern of effects from urbanization, such as gentrification, privatization of public spaces and services, basic urban segregation, the precariousness of the neighborhoods of the poor, the increase of informal settlements, the use of public investments to promote projects and infrastructure that only meet business or economic interests, indicate that new ways of life and development in cities need to be adopted in the New Urban Agenda. For this reason, the New Urban Agenda must embrace a change in the predominant urban pattern that increases urban equity, social inclusion, and political participation, and provides a decent life for the urban population.

The most important outcome of Habitat III is the emergence of the Right to the City at the center of the New Urban Agenda.

The New Urban Agenda should recognize that current urban development patterns are based on the premise of attracting business and commodification of land and the speculation that results from it will not be able to create a model of sustainable social inclusion, citizenship, democracy, cultural diversity, and high quality of life in our cities. This agenda needs a diferent paradigm to establish the link between social inclusion, participatory democracy, and human rights to make the cities inclusive, fair, democratic, and sustainable.