“Urban commons: the goods, tangible, intangible, and digital, that citizens and the Administration, [through] participative and deliberative procedures, recognize to be functional to the individual and collective wellbeing…to share the responsibility with the Administration of their care or regeneration in order to improve [their] collective enjoyment”

—From Section 2 of the “Regulation On the Collaboration Among Citizens and The City for The Care and Regeneration Of Urban Commons”, City of Bologna, Italy

When the ecologist Garret Hardin wrote his much celebrated essay in 1968, “The Tragedy of the Commons”, no one would have imagined that the concept of the commons would apply to the built environment. Yet today, the “urban commons” is increasingly embraced by scholars, activists, citymakers, policymakers, and politicians. These urban commons can include a range of resources in cities—including parks, community gardens, streets, neighborhood infrastructure, vacant lots, and abandoned buildings. The urban commons also include the intangible aspects of city living, such as culture and heritage. Characterizing these resources as urban commons re-imagines the city as a collection of shared resources and its residents as potential collaborators in generating, utilizing, and managing these resources.

When widely and intensely shared urban resources increase solidarity and generative potential, they can invert the tragedy of the commons paradigm.

But why exactly are these urban “commons” or common goods? These terms are not always subject to precise definition. The term urban commons, in fact, can give rise to more questions than answers. What is the difference between natural resources (traditional commons) within cities and abandoned buildings or vacant lots that are turned into a common pool asset by urban residents? What is the difference between privately governed open access spaces and cooperatively governed open access spaces—are they both types of urban commons? Can certain kinds of infrastructure—broadband infrastructure, do it yourself “mesh” networks, new forms of energy (like microgrids), housing cooperatives, etc.—be considered common goods? These are important questions to answer if this framework of the urban commons is to have any lasting impact on our discussions about what cities can or should become as we undergo intense urbanization in the next few decades.

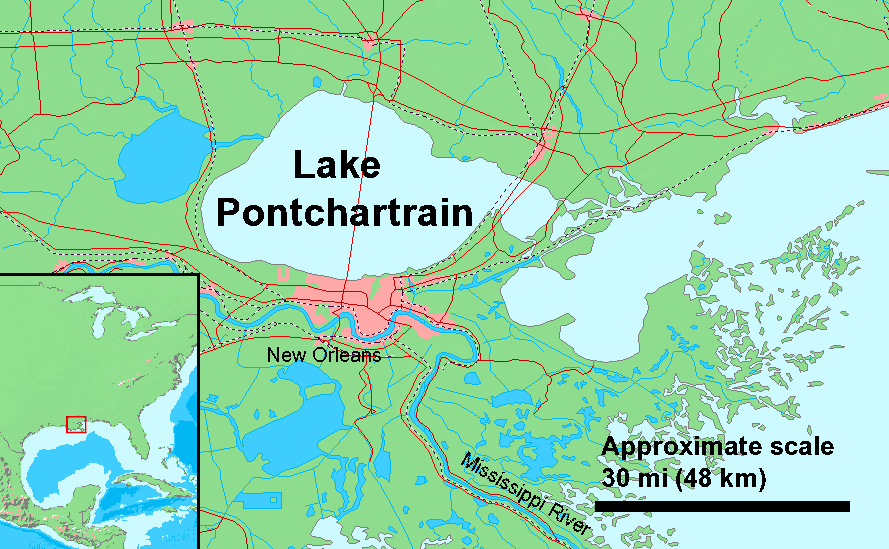

Let’s begin with Hardin’s original, though simplistic, conception of the commons—an open access natural resource. Hardin’s tale of “Tragedy” unfolds in an open pasture in which individual herdsmen bring their cattle for grazing until their combined actions lead to overgrazing, essentially depleting the resource entirely. There are, of course, traditional, open access natural resources in urban environments, around which cities have been built and are now part of their ecological landscape. Lakes, rivers, and wetlands in and around cities are certainly a type of “urban commons”, as Harini Nagendra’s wonderful work and blogging illustrate. The degradation and destruction of these resources as a byproduct of urban development is a concern for the sustainability of cities at a time of obvious climate change. New Orleans, for instance, was built on a marsh and is surrounded by the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain. It is not difficult, for instance, to trace the loss and destruction of coastal wetlands over the course of a century (or more) to the devastating flooding that occurred in New Orleans as a result of Hurricane Katrina.

Moreover, much of the infrastructure of a city is an open-access commons—including its streets, parks, plazas, and squares. It is not difficult to imagine how many of these open access, public spaces can result in an urbanized version of Hardin’s Tragedy—overconsumed, degraded, or destroyed. This “tragedy” was arguably reflected in the decline of many open spaces in U.S. cities in the 1970s and 1980s, which left many streets, parks, and neighborhoods unsafe, dirty, prone to criminal activity and virtually abandoned by most users. Much of this decline in the urban commons was attributable not only to over-consumption and degradation, but equally to the onset of local fiscal crises and decline in city appropriations to care for and regulate these spaces, arguably sealing their fate for at least a decade or more.

Most of the focus on the urban commons, however, is not about threatened or endangered natural resources in cities, nor about the tragedy of the urban commons. The push to recognize the built environment as constituting a variety of urban commons is more about opening up access to, and generating, essential resources for a broader class of individuals than is fostered by current urban growth and consumption patterns. This recognition resists the threat of enclosure of the city resources and assets— parks, public spaces and institutions, vacant and abandoned land, underutilized structures, among others—by either public or private appropriation and control. Exclusive public or private management and control tends to monopolize these resources and subject them to domination by elite interests or to the speculative market. The enclosure of these elements of the urban mosaic by narrow interests and capital markets prevents the kind of sharing and pooling consistent with the idea of a commons as a collective, shared resource.

Let’s return for a moment to parks, streets, neighborhoods, and other infrastructure in cities and flip the script from Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons” to what Carol Rose calls the “comedy of the commons.” These open access spaces in cities are where the proximity of different kinds of people coming together creates the culture and “vibe” of a city and strengthens social ties within communities. It is this interaction among urban dwellers that makes public space so valuable in cities, and in communities. This openness is crucial to the ability of great cities to thrive amidst tremendous human diversity. As such, increased use and even congestion in open access, interactive spaces are what gives urban commons their value as a shared resource. The more of the public that participates or joins in to utilize the resource, the more valuable the resource is to the individuals or communities that use it. As Carol Rose argues, rather than tragedy in these spaces, we are more likely to find that the “more the merrier” is a better description of high consumption activities in the urban commons. In other words, the more that people come together to interact, the more they “reinforce the solidarity and well-being of the whole community.” Thus, instead of the potential for overconsumption and ruin, we can also imagine the potential for solidarity and the generative potential of the urban commons to create other goods that sustain communities.

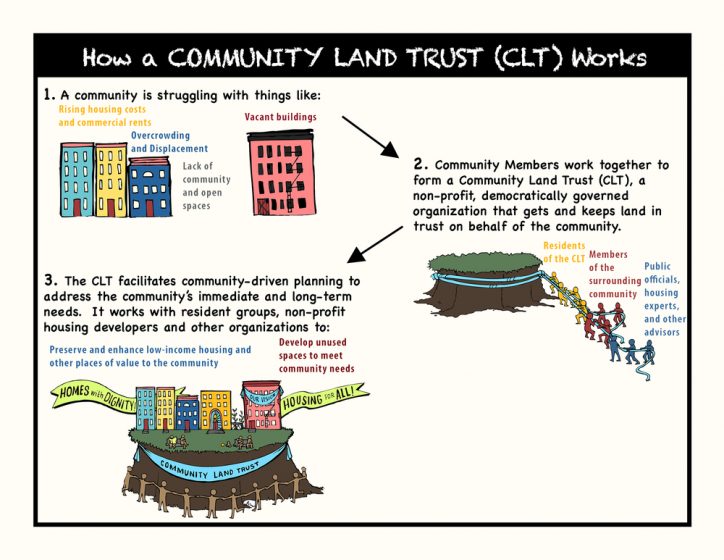

The most transformative vision of the urban commons is a recognition that common goods can be cooperatively or collaboratively produced and managed by urban residents in ways that are more attuned to the needs of those users and more inclusive of their input. When residents clear vacant lots and construct community gardens and urban farms on them, they not only facilitate and reinforce their solidarity, but they also produce a host of other goods (public safety, outdoor green space, fresh food) necessary to function and to flourish in healthy, sustainable communities. When activists occupy and squat in foreclosed and abandoned (and often boarded up) homes or public housing units as a means to convince municipalities to clear title and transfer these homes into communal forms of ownership and management, they do so to take the properties out of the speculative real estate market and create limited equity housing or long-term affordable rentals. Transferring previously held structures to a community land trust, or converting them into deed-restricted housing, would keep these properties perpetually affordable for low- and moderate-income households and would allow the residents to self-manage them as an urban commons.

Housing cooperatives have a long history in American cities. However, the use of community land trusts (or CLTs) and other cooperative ownership structures that separate land ownership from land use transform what might otherwise be a collection of individuals owning property (in the typical cooperative ownership model) to a collaboratively governed institution which manages collectively shared goods. Land owned by a CLT is removed from the real estate market and put into a legal structure that is democratically governed by a diverse membership open to people from across the city or a specific community. For example, community land trusts can manage housing, commercial real estate, green space, small businesses, and indeed an entire urban village as in the celebrated example of the “urban village” managed by Dudley Street’s Neighborhood Initiative in the Boston area.

The emergence of collaboratively generated and cooperatively managed regimes to take care of and regenerate the urban commons is very reminiscent of the groundbreaking work of Nobel prize winner Elinor Ostrom. In her classic work, Governing the Commons, Ostrom identified groups of users all over the world who were able to cooperate to create and enforce rules for sharing and managing natural resources—such as grazing lands, fisheries, forests, and irrigation waters—using “rich mixtures of public and private instrumentalities.” In such frameworks, we see novel applications of collaboratively managed infrastructure and goods and services that have typically been provided as either public or private goods. There are many emerging examples of the creation of common goods in the environmental, housing, digital, and cultural arenas.

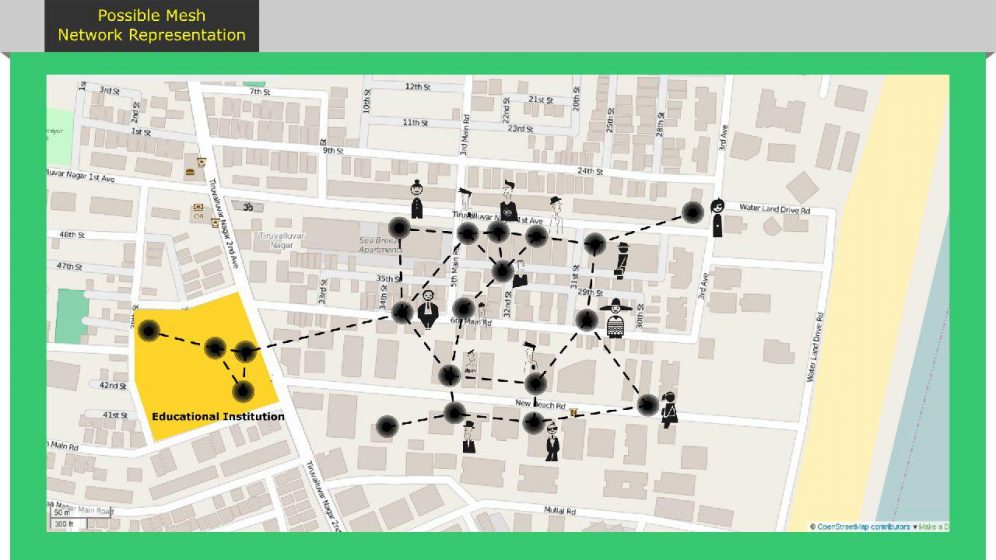

In New York City, there is an emerging “real estate investment cooperative” (or REIC) to finance the transformation of vacant publicly owned buildings for community, commercial, and manufacturing spaces. All of the spaces that the NYC REIC finances will be transformed into permanently affordable space. There are also efforts underway to create new forms of collectively owned and cooperatively managed urban infrastructure, particularly in socially and economically vulnerable communities. For example, community wireless mesh networks (as in Red Hook, Brooklyn) can bring internet service to communities and populations that lack broadband access. These networks can help to bridge the digital divide and promote what some call “network equality”, as well as providing resiliency in case of a climate event. Similarly, and also to address resiliency to climate change in neighborhoods less likely to withstand climate change impacts, some communities (as in West Harlem New York) are exploring installing cooperatively owned microgrids as a way to transition towards more resilient communities.

Finally, beyond particular urban commons, the city itself is a commons—a shared resource that is generative and produces goods for human need and human flourishing. The city as a commons means that the city is a collaborative space in which urban inhabitants are central actors in managing and governing city life and urban resources—ranging from open spaces and buildings to neighborhood infrastructure and digital networks. Moreover, the city (as a public authority) can and should be one partner in a polycentric system creating conditions where urban commons can flourish.

This idea of the city as a commons is motivated by the ongoing experimentation process of establishing Bologna, Italy, as a collaborative city, or “co-city.” As part of this process the city of Bologna adopted and implemented a regulation that empowers residents, and others, to collaborate with the city to undertake the “care and regeneration” of the “urban commons” across the city through “collaboration pacts” or agreements. The regulation provides for local authorities to transfer technical and monetary support to reinforce the pacts and contains norms and guidance on the importance of maintaining the inclusiveness and openness of the resource, of proportionality in protecting the public interest, and of directing the use of common resources towards the “differentiated” public. The specific applications of the Bologna regulation are just now undergoing implementation, as the City has recently signed over 250 pacts of collaboration, which are tools of shared governance. The regulation and other city public policies foresee other governance tools inspired by the collaborative and polycentric design principles underlying the Regulation.

The Bologna regulation, and the related co-city protocol designed by my colleagues at the Laboratory for the Governance of the Commons (“LabGov”) are illustrative of the kinds of experimentalist and adaptive policy tools which allow city inhabitants and various actors (i.e., social innovators, local entrepreneurs, civil society organizations, and knowledge institutions willing to work in the general interest) to enter into co-design processes with the city, leading to local polycentric governance of an array of common goods in the city. This process of commons-based experimentalism re-conceptualizes urban governance along the same lines as the right to the city, creating a juridical framework for city rights. Through collaborative, polycentric governance-based experiments we can see the right to the city framework be partially realized—e.g., the right to be part of the creation of the city, the right to be part of the decision-making processes shaping the lives of city inhabitants, and the right of inhabitants to shape decisions about the collective resources in which all urban inhabitants have a stake.

Sheila Foster

New York City

Leave a Reply