In a previous contribution to The Nature of Cities (Faggi & Vidal 2016), we wrote about linear parks (LPs) as an interesting green space typology and discussed some strengths and threats of these multifunctional areas in Latin America. Other contributions (Tsur 2014, Das 2015, Maddox 2016) explained that LPs are good answers to create more access to green and open space in cities that don’t have much space to spare.

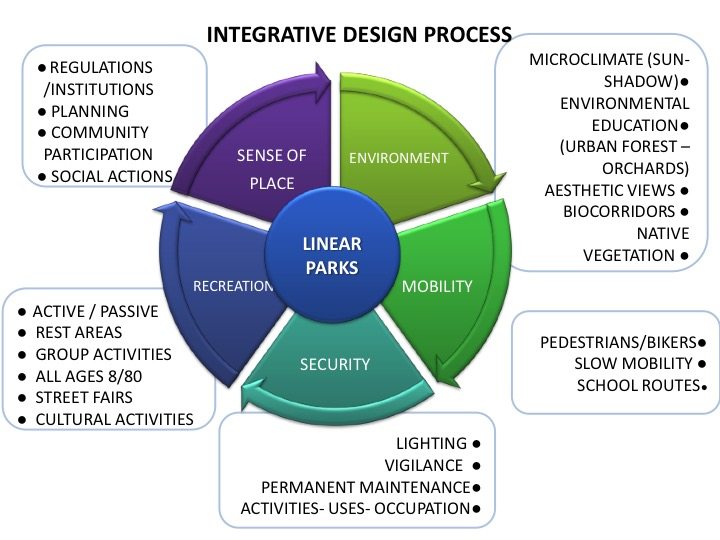

In planning the layout of a linear park using a successful integrative design process, it is paramount to consider users’ perceptions and attitudes.

Linear parks include greenways, waterfronts, and transportation infrastructure, frequently in re-used sites linking major urban nodes. Unlike other types of green areas, people use LPs for moderate and vigorous physical activities. In the last decade, linear parks received a great deal of attention among city planners as an opportunity to revitalize interstitial edge-spaces in the post-industrial era. In many cities, they are being planned as drivers for the regeneration of deprived areas and for residents to be physically active.

People relate to linear parks not as a uniform space, but rather as a hierarchy of different supplies which provide a range of benefits that enable active and passive recreational experiences. Each linear park may be seen as having more or fewer cultural, ecological, developmental, agricultural, and recreational values. Each linear park type has its own appeal, and each park is filled with an array of elements to shape its character, creating individual feelings along with the experiences people have when they use the park.

One of the first questions designers should ask themselves about their projects is for whom and for what are these linear parks being designed? In addition, they should explore what the target community most values about linear parks?

For example: which park’s features are residents particularly interested in?:

- Is an identifiable location of the park within the urban matrix, easy access, and secure connections across the LP and with other places in the city most important? Surely these variables will be appreciated by most of the visitors, and will have a decisive impact on public attendance.

- Are users more interested in the environmental quality of the LP? These traits will be prioritized for those with environmental feeling—a sector of the population that already knows how important urban green space is for environmental benefits such as biodiversity, cleaning and cooling the air, or slowing down runoff.

- Or, will the visitors prefer nature-based recreational areas ideal for fishing, boating, hiking, biking, birding, or scenic views, and access to the sky and to the horizon line?

When linear parks are designed, conflicts frequently arise. Sometimes, there is a lack of articulation between environmental function, social use, city regulations, and institutionalism. Other factors that play against linear parks are perceptions of insecurity, the community’s unconcern, lack of planning, and lack of cross disciplinary work. For example, the LP of Palmira city (Colombia) draws substantial apathy from the city’s residents. Lack of a sense of belonging and of environmental sensitivity, coupled with the perception of insecurity in the park, compound the lack of interest of the local authorities. This lack of synergy between community and government is what prevents the park from reaching the splendor it deserves and from which all would benefit.

In planning the layout of a linear park in a successful integrative design process (below), it is paramount to consider users’ perceptions and attitudes by examining the interplay between public life and public space.

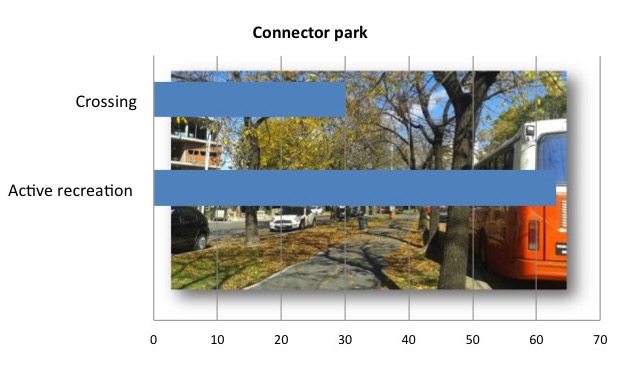

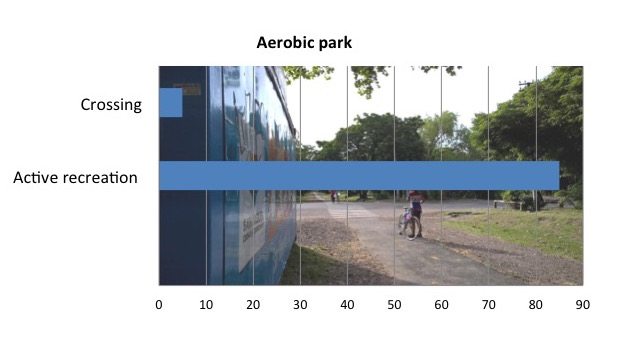

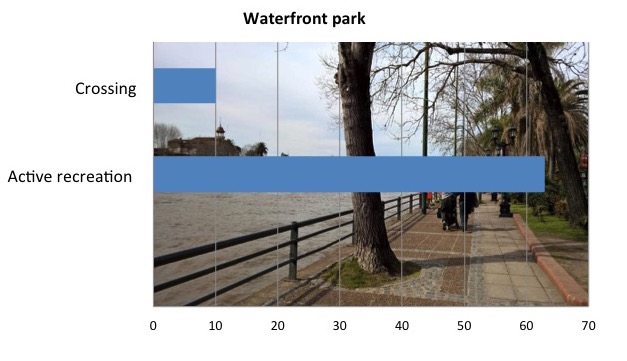

Last year, we studied a set of six linear parks in Argentina and Colombia. In our analysis of them, we delineated three different types classified as: Connector, Aerobic, and Waterfront linear park.

We found that that these three different types differed in the quantity and quality of the services they provided and on the way these parks were perceived by the public. We made our categorizations according to accessibility, neighboring land-use (urban complexity), connectivity, vegetation cover, paved surfaces, infrastructure, and how people use the areas by performing active and passive recreation.

For the active physical activities, we considered percentages of walking, crossing, running, cycling, rollerskating, skateboarding, playing ball, soccer, other games, riding, aerobics, fishing, and boating.

Passive recreation included: social interaction, walking the dog, eating/drinking, sitting, lying, sunbathing, and reading.

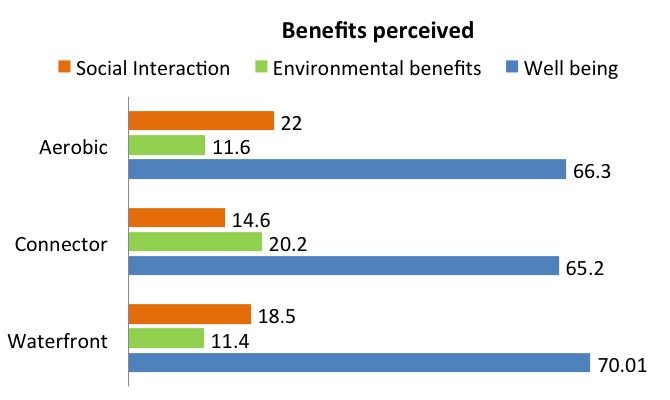

Our results showed that the proportion of active recreation and of crossing were the features that discriminate between types (Fig. 2). Other interesting differences we recorded among parks were the perceived benefits mentioned by users (Fig. 3). The waterfront LP was the one that reached the highest value of well-being (physical and psychological benefits).

Connector linear parks: What we have called “connector linear parks” are mainly used as commuting axes—cool and quiet routes through which to pass on the way to other destinations, such as shops, services, and bus stops. It is known that natural settings with good access and amenities encourage people to walk for transport (Gehl 2010). Both in Buenos Aires and in Palmira, these LPs connected services and commercial areas, as well as parks and squares. Respondents gave them the highest values of environmental benefits and the lowest of social interaction.

Aerobic linear parks: These play a dominant role in daily recreation because they provide the greatest overall physical benefit, as indicated by active recreation (running, cycling, rollerskating, skateboarding) scoring highest in this type of park. This type does more than pretty up a district; it has an improvement effect on residents` health and well-being.

Waterfront linear parks: These are somewhat similar to the connector park type in the amount of active recreation that they support, but waterfront linear parks are used less for commuting and more for contemplating the landscape. They also have great potential as meeting points for social events. Other significant activities in this park type are actions linked with water, such as fishing, boating, and reflection. There is substantive evidence, for instance, that water gives a landscape a special appeal. Architects, designers, planners, psychologists, and researchers interested in environmental behavior have consistently reported the presence of water as one of the most important and attractive visual elements of a natural or built landscape.

As these types of parks are used in different ways and have their own distinctive character, they require specific infrastructure to sustain their individuality. Such contrasting features should be taken into account in the early phases of their design process. In terms of management, this early incorporation can make a project more successful.

If a park already exists and shows dysfunctional instrumental effects, a redevelopment is necessary. The application of corrective measures seeking solutions should be based on the different functionality of different types of parks.

In our study case, the lack of adequate infrastructure revealed that, in the design, the park features previously mentioned were underestimated. This experience enables us to develop recommendations for future interventions that should be used to reinforce the park’s identity (below).

We have shown that design and location are keystones to what makes a successful linear park. Approaches to design must vary to suit the scope of the park, as its design influences how the place will be managed and used, not to mention that a green and pleasant area that is well-planned and well-managed is generally a well-used space! To achieve these goals, cross-disciplinary good practices will ensure that existing LPs settings can be better promoted or modified.

Ana Faggi, Claudia Zuleyka Vidal, Florencia Gusteler, and Romina Lopez

Buenos Aires and Cali

References

Das PK (2015). Let Streams of Linear Open Spaces Flow Across Urban Landscapes. The Nature of Cities (August 12, 2015).

Tsur N (2014).The Story of Jerusalem’s Railway Park: Getting the City Back on Track, Economically, Environmentally and Socially. The Nature of Cities (August 18, 2014).

Faggi A, Vidal CZ (2016). Linear Parks: Meeting People’s Everyday Needs for Secure Recreation, Commuting, and Access to Nature. The Nature of Cities (April 14, 2016).

Gehl J (2010) Cities for People. Island Press.

Maddox D (2016). Justice and Geometry in the Form of Linear Parks The Nature of Cities (April 18, 2016).

about the writer

Claudia Zuleyka Vidal

Claudia Zuleyka Vidal is an architect with many years’ experience in a wide range of urban renewal design projects. At present, she is working on a variety of architecture projects in the city of Cali.

about the writer

Florencia Gustelar

Florencia Gusteler is an Environmental Engineering student at Flores University, Buenos Aires.

about the writer

Romina Lopez

Romina Lopez is an Environmental Engineering student at Flores University, Buenos Aires.

Leave a Reply