about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Introduction / Prompt

In the creation of better cities, urban ecologists and landscape architects have a lot in common: to create and/or facilitate natural environments that are good for both people and nature. Mostly. Some may tilt toward the built side, some to the wild. Some may gravitate to people, others to biodiversity, form or ecological function, or social function, or beauty.

There are a lot of shared values. And yet, they are still two distinct professions, ecology and design, and so there are ways in which we may say similar sounding things but mean something different. Steven Handel wrote in this space to analogize ecology and landscape architecture to a marriage: it takes work to make all that love and harmony happen.

Built into this roundtable prompt is certainly an issue of communication. That is, the possibility that, if we just talked to each other more, and more effectively, everything would be fine. But it is also possible that value sets do not exactly align. If you had to choose, what is the most important thing to consider? The responses in this roundtable include development of a unified vocabulary and suggestions of more integrated training, collaboration that functions throughout a project’s duration, start to finish, and ideas beyond.

So, get it off your chest. What is something your partner in environmental city building, the other profession, just doesn’t get about you? And what would it take it fix it? Or, if you don’t like the marriage metaphor, what are one or two key ideas from your profession’s beliefs and way of working that are not making it over to the other profession in a complete and true form? How can we get landscape architecture and ecology better integrated in the service of better cities?

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers expressed it quite well, singing the words of George Gershwin in Shall We Dance:

You say to-MAY-to, I say to-MAH-to

You eat po-TAY-to and I eat po-TOT-o

To-MAY-to, to-MAH-to, po-TAY-to, po-TOT-o

Let’s call the whole thing offBut oh, if we call the whole thing off then we must part

And oh, if we ever part then that might break my heart—”Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off” by George Gershwin (from Shall We Dance)

Here’s how Fred and Ginger said it, in a park, no less. And even if you don’t read another word of this roundtable, check out the dance number (including tap!) on skates.

We all have our points of view. Someone said about Rogers and Astaire: “Sure he was great, but don’t forget that Ginger Rogers did everything he did…backwards and in high heels.”

Better call the calling off, off. Because, in the meantime, the stakes of getting city design right are high. And in diversity and collaboration, the spice of life creates new paths.

about the writer

Mary Cadenasso

Mary L. Cadenasso is a landscape and urban ecologist interested in how the heterogeneity of a system influences ecological processes in that system. She is a professor of Plant Sciences at the University of California, Davis.

Mary Cadenasso

Urban ecologists and landscape architects are both interested in the structure or form of urban land. While an ecologist may investigate how the structure of the land influences, and is influenced by, ecological processes, landscape architects have a more direct hand in actually shaping that land. An idea from ecology crucial for understanding how cities work and for guiding efforts to create better cities is the reciprocal link between the spatial heterogeneity, or structure, of urban systems and the ecological functioning of that system.

The studio training of a landscape architect offers a setting ripe for fostering meaningful interaction between the disciplines.

Heterogeneity is fundamental to general ecological theory because of this hypothesized link between it and ecosystem functioning. In its most basic definition, heterogeneity is the spatial variation in at least one variable of interest, and urban heterogeneity consists of the spatial differentiation of biological, physical and social structures of urban areas. Specific descriptions of heterogeneity may include zones of different land use types, maps of socially bounded neighborhoods, or areas of greater or lesser vegetation diversity. These heterogeneities may influence the flow of nutrients and pollutants, the diversity of organisms, or the amount of carbon stored, for example. Because landscape architects can fundamentally alter the spatial heterogeneity of urban systems, recognizing the ecological functioning of that heterogeneity is crucial in order to incorporate heterogeneity into designs in a way that maximizes positive ecological outcomes and minimizes negative outcomes of the design.

Of course, landscape architects incorporate heterogeneity into designs; heterogeneity in the physical or biological structure of the landscape can be aesthetically pleasing. Conveying the style or signature of the designer is important so that their work is recognized, but how can heterogeneity be used functionally and not just stylistically? Sometimes designed heterogeneity is constrained to the boundaries of the specific project and in other cases the design integrates the project with adjacent areas. Flows of people across boundaries are usually considered, but how about the flows of nutrients and pollutants, non-human organisms, information, etc.? How would the design differ if it explicitly considered both the ecological processes occurring in the specific project area and the ecological flows across the boundary between the project site and the adjacent landscape?

Because both disciplines share an interest in the structure of urban land, the potential for integrating the work of ecologists and landscape architects is enormous. The studio training of a landscape architect offers a setting ripe for fostering meaningful interaction between the disciplines. I, along with colleagues, have had the privilege of engaging with landscape architecture students in their studio courses as they work on design ideas throughout a term. We provided a broad overview of ecological concepts relevant to design in a seminar format but that was of limited utility. More productive was time spent together walking the project site and talking casually about what we each were seeing through our respective disciplinary lenses. In this casual setting, we could build trust and share the motivations and assumptions we each hold. We could also discuss design scenarios to achieve stated goals and the potential ecological implications of each scenario. After that “walk and talk”, we ecologists went away until the end of the term, when we attended the charrette, listened to the students’ presentations of their work, and provided feedback. Feedback at the end of the term is useful but, again, limited. The second time we contributed to a studio class, and every time following, we participated in “desk crits” at regular intervals. This process of literally dragging a chair from desk to desk to engage with students over their ideas and designs added an incredible richness to our conversations and allowed us to collaboratively make modifications to the design. For example, the use of a particular tree species in a design may be driven by the quality of shade it throws, and the tree’s size and shape. In conversation about resource needs of the tree, perhaps a different species that could provide those same characteristics but also be more appropriate for the climate could be substituted, or the number and arrangement of trees could be discussed relative to the flow of resources.

As an ecologist, learning the motivations, assumptions, processes, and constraints that a landscape architect experiences in the process of design was informative for how to communicate lessons from research and, excitingly, these collaborative conversations also sparked new research ideas for testing the link between urban heterogeneity and system function. Working collaboratively in a studio setting requires intellectual openness and a desire to learn from the other discipline. Participants have to be willing to be surprised, confused, and challenged respectfully in order to learn a different way of thinking. Obviously, this takes a certain personality and combination of personalities, and sometimes it will fail. But when it works, it can be enormously valuable because of the ideas generated and the new ways of thinking developed and shared.

about the writer

Andrew Grant

Andrew formed Grant Associates in 1997 to explore the emerging frontiers of landscape architecture within sustainable development. He has a fascination with creative ecology and the promotion of quality and innovation in landscape design. Each of his projects responds to the place, its inherent ecology and its people.

Andrew Grant

Of all the ecologists I have worked with in 30 years of professional life, I would like to promote Dr. Mike Wells as a great example of an ecologist who understands how to inform, enthuse and encourage landscape architects and, also, when needed, to challenge and question their ideas.

It’s not really about the respective roles of ecologists and landscape architects that will make a difference. It is how we are engaged by the powers that be, either public or private, in the challenges of city planning and design.

Mike has a particular ability to think outside the usual confines of ecology and science to find inspiring ecological options and I want more ecologists to be similarly creative in their thinking because we need a step change in the way we work on city planning and design issues. We are making headway in getting green and blue and health and food issues into the city planning debate, but are we really offering the ecological vision needed to push us out the other side of the global problems?

If ecologists need to get in touch with their imagination, then landscape architects need to learn more effective ways to process and apply ecological principles into urban schemes. We can only bring change if we act together to deliver the planning, design and management of more ecologically sound and inspiring, socially inclusive city environments.

This triple-layered objective to deliver Ecological, Inspirational, Purposeful urban landscapes should be our focus. Ecologists need to realize that arguments based on ecosystem services or species diversity are only half the answer, and landscape architects who are entirely obsessed with aesthetics, function, and experience are only offering the other half. We need both professions fused together in each and every urban project.

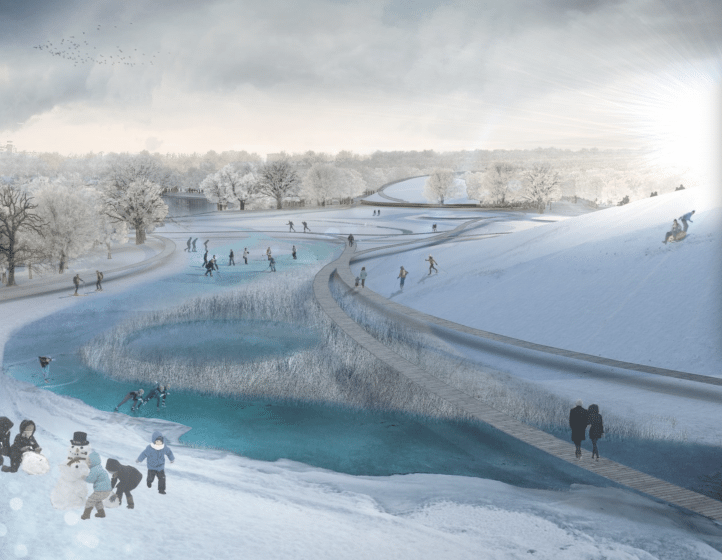

Of the above objectives, I believe ‘Inspirational’ is the least understood, but a crucial ingredient. If we are to change our behaviour and values to achieve a more sustainable urban future, we need to be inspired to do so. Much of the output of current ecology and landscape design derives from tired and traditional models and, whilst there are exceptions, I believe more than ever that we need radically new landscape interventions within cities that challenge our notions of the traditional patterns and components of urban landscapes. In addition to places for play, food, sport and leisure, I want to bring the awe and surprise you get when you see a natural wonder right in the heart of the densest urban areas. Magnificent waterfalls, dense forest, characterful rock outcrops—landscapes in scale with the new urban fabric that become the social media memories of the city.

While I see the role of landscape architects as communicating and implementing designs of the scale, purpose, and physical expression of such interventions, I would like to see more ecologists stretching their imagination to define new approaches to ecosystem design that allows the evolution of entirely new habitat types and systems that help bring these places to life and put nature at the doorstep of every urban resident and worker.

However, it’s not really about the respective roles of ecologists and landscape architects that will make a difference. It is how we are engaged by the powers that be, either public or private, in the challenges of city planning and design. We need a step change in perception of our joint value.

The television series “Thunderbirds” made a big impression on me as a kid. Palm trees that can be flipped over to make space for a runway. Amazing scenery, jets, cars, submarines and spaceships. A sense of saving the world and a global perspective in the guise of International Rescue. The best bit was always the choice of vehicle to tackle that episode’s challenge. Would it be the Mole or Thunderbird 1? Would it be Brains or Lady Penelope? In each case, the right person or device or combination of all was deployed to save the day. Teamwork was fundamental to every episode.

How great it would be if we could tackle the challenges of ecological city planning and design with such clarity. A wise client selecting the right professions and process to tackle each new challenge. An ecologist cracking a specific species conservation strategy or outlining the principles for a neighbourhood-specific ecosystem alongside a landscape architect shaping a space that lifts the spirits and creates another functioning piece of the city. Always a future-focused team, but with the right emphasis for each challenge. That would be almost perfect. We just need Tracy Island as our base.

about the writer

Marcus Hedblom

Marcus Hedblom is a researcher and analysist at the Swedish University of Agricultural sciences.

Marcus Hedblom

Many cities globally still have rather large natural remnants within the cities. What I refer to as remnant nature in this text includes woodlands or urban forests. These remnants do sometimes have unique prerequisites for biodiversity. Meaning, these urban woodlands have additional values that forests outside cities do not have.

Building parks seems deeply rooted in planning, but there are major and important differences between parks and natural remnants.

These values are linked to the fact that forests in cities are not under timber production command and have different aged trees, shrubs, and dead wood—things that are removed in production forest, but which are important for biodiversity. Thus, urban woodlands can have as high biodiversity as other forests but also provide unique habitats for hole-nesting birds, for example, due to older trees and dead wood. Sweden has high coverage of forest, with 55 percent coverage, but out of these, 97 percent of the forests is for production. This means that most forests in Sweden are monocultures of one species, with equal ages in large areas and almost no dead wood. This also means that deciduous species are lacking in the landscape since coniferous species have higher production values.

In cities, however, woodlands are mostly left for future expansion or for recreational purposes and not for production. This allows trees to get old and also allows for a mixture of species. In Sweden, urban woodlands in the urban fringe have more dead wood than the forests outside cities, and deciduous bird species are in higher abundances in cities. However, these urban woodlands are threatened. The main threat is the densification trend of cities where forests are removed. Often, the previous forest are totally removed and replaced by a smaller park. It is very unusual that the already old and existing trees—nature remnants—are kept for the new area.

The second threat is what I refer to as “parkification”. This is when dead wood is removed for safety and aesthetic reasons; saplings are removed, and thus the understory of the woods is cleared (also for safety and aesthetical reasons) and some unwanted trees are removed, such as large coniferous trees. In the end, the forest looks more like a park than a natural remnant.

Here comes the interesting link between the ecologist (me) and landscape architects. Because when I worked at the municipality of Uppsala (4th biggest city Sweden), my landscape architecture colleagues said that parks where the same as nature. And my colleagues influenced the strategic planning map of the whole municipality. Thus, when a natural remnant was removed on the strategic municipal plan and replaced by a park, it was marked as green on the map—the same green colour as the nature parts in the city. At least, this was done on the bigger official maps. It then looks like nature has been kept in the city, although forests have been “changed” to parks. I had real trouble with this, since I believe that there are major and important differences between parks and natural remnants. This might be self-evident to most of you, and maybe my writing is one case of a problem in a small Swedish town, without similar perspectives elsewhere. But travelling around in cities on all continents, it is striking how parks dominate in the city and also how they all look the same, with lawns, some trees that are not indigenous, and some flower beds.

Thus, parks dominate cities, although new research shows that there are higher aesthetic perceptions in natural remnants than in parks. Also, biodiversity per se increases positive perceptions of urban settings, e.g., many native bird species that sing increase positive perceptions more than only a few species. These birds thrive in urban woodlands, but they don’t flourish in the same diversity in parks. Further, it is very common that parks to a large extent have lawns. Lawns are mostly monocultures, reducing the number of pollinators. Given these factors, biodiversity may be considered to be highest in natural areas. Interestingly, new research shows that many people, though not everyone, prefer meadows with large flowerbeds rather than lawns. Meadows have a much higher variety of flowers and allow a diversity of butterflies. It is possible to keep urban woodlands or meadows that are safe and provide high aesthetics.

Why do we then continue to build parks with lawns when natural areas provide biodiversity and well-being in higher extent than parks? Building parks seems deeply rooted in planning. It is also somewhat provoking, for me at least, that parks are considered to be nature. The urban green areas in cities, and especially in mega-cities, may be the only “nature” people experience. Experiencing nature in cities has been demonstrated to lead to a deeper understanding of nature elsewhere. So, with an ever increasing proportion of humanity living in cities, it is important to provide natural settings, not only for health and higher aesthetic experiences, but also for an understanding of the natural environment outside cities. In a majority of Sweden, you can easily still reach forests in the urban fringes that resemble virgin forests, but for how long?

Scientific references:

Ignatieva M, Eriksson F, Eriksson T, Berg P, Hedblom M. 2017. Lawn as a social and cultural phenomenon in Sweden. Urban Forest & Urban Greening. 21:213-223.

Nielsen AB, Hedblom M, Stahl Olafsson A, Wiström B. 2016. Spatial configurations of urban forest in Denmark and Sweden – patterns for green infrastructure planning. Urban Ecosystems. DOI 10.1007/s11252-016-0600-y

Ode-Sang Å, Gunnarsson B, Knez I, Hedblom M. 2016. The effects of naturalness, gender, and age on how urban green space is perceived and used. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 18: 268–276.

Gunnarsson B, Knez I, Hedblom M, Ode Sang Å. 2016. Effects of biodiversity and environment-related attitude on perception of urban green space. Urban Ecosystems. DOI 10.1007/s11252-016-0581-x

Hedblom M and Söderström B. 2008. Woodlands across Swedish urban gradients: Status, structure and management implications. Landscape and Urban Planning. 84:62-73.

about the writer

Steven Handel

Steven Handel is a restoration ecologist and the director of the Center for Urban Restoration Ecology (CURE), an academic unit at Rutgers University.

Steven Handel

I’m shy, but I think we have a lot to offer each other. You designers know so much and have so much to offer to the public. Space maker’s designs satisfy so many programming needs for the public. I can complement your skills in new ways, and I think we’d be a really attractive couple.

I know we haven’t grown up together or even gone to school together, you over there in the design school and me stuck with the scientists across campus. but invite me to the public works dance, please.

I can bring so many ecological services to your side. These are recognized more and more as valuable to people and even save on budgets for public officials. I know you’re interested in stormwater management and the joy of cultural services, the aesthetic thrill of walking in a modern, designed landscape. I can add cleaner and cooler air, the sounds of nature, and the binding of soil to keep your waterways clear. My work can even add pollinators, enhancing the urban agriculture that so many folks are interested in these days. In this way, our partnership can make you seem more fiscally responsible and folks will really like that. I can help you on so many scales, giving you an ecological foundation for all your work. From a roadside planting to a green roof to a grand-scale public park. I know there are ecological perspectives that can be plugged in to make your work even better. So often, ecological features are really seen as engineering tools, cutting down on runoff or using green insulation keeping buildings cool. There is so much I can do, if you give me a chance.

I know you may have heard some bad things about me and I know some people are fearful of hanging out with ecologists. Sure, there are rumors of ecological disservices, parts of my perspective that people fear: biting insects in public parks, funny odors, critters that might carry diseases; who needs them, some people say. I talk about thickets of native shrubs on the landscape, and people are nervous that muggers may hide there. But with communication and understanding, I can explain to people that these things are overblown and the value of having me around much outweighs these irrational fears. We know these communication gaps can be a real problem, but with time and honesty, we can overcome them.

I know we haven’t grown up together or even gone to school together, you over there in the design school and me stuck with the scientists across campus. Nevertheless, if we do meet, I think we can have a swell time together. I’d like to be with you from the very beginning of a project, when we lay out design features and the interplay of all the elements that are on your mind. If we meet later in the process, too much is set in stone, literally, and there is no room for me in your life. If we meet early, when the proposed project is young, we can grow it up together and be real partners. So many RFPs don’t even mention me. They see a public work as needing architects and engineers and traffic consultants and lighting specialists. People like me who think about food webs and biodiversity and natural heritage are rarely invited to the table of public work design. Let’s try some small projects together, talking about landscape on a coffee date or on a quiet walk through an industrial park that’s being redesigned. That’s not a big commitment, and I think it could lead to some really great times together. Then, people will start wanting us to attend a big public work events.

I’ve been hugging trees for a long time, but earning a general affection by the public will take a long-term courtship, I’m afraid. Give me a call and let’s see if we can get this relationship going.

about the writer

AnaLuisa Artesi

Ana Luisa Artesi is Head and Founder of the studio Ar&A – Arquitectura y Ambiente, an interdisciplinary office, whose focus is on highways, private and public landscapes, individual houses, multi-family buildings and housing developments

about the writer

Veronica Fabio

Verónica Fabio is the Director of the landscape studio Verónica Fabio and Associates since 1985, specializing in the design of public and private space, both small and large scales.

Ana Luisa Artesi and Vero Fabio

The Landscape, Connector

Cities are the setting and the resultant of the dynamic relations and tensions between nature and human culture, in constant transformation.

The creation of sustainable projects can be achieved only by acting in coordination and direct relationship with professionals from many disciplines.

Conceptually, Natural Landscape—no longer original but the result of evolution—is the integrator of life, a service provider, a connector of the various superimposed frames. The continuity of landscape is the nexus and support for the dynamics of Biodiversity.

On the one hand, Landscape Architects’ projects can generate substantial change (sometimes permanent) that may affect the environment, not only in immediately apparent ways, but also in underlying and subjective values.

On the other hand, the Urban Ecologists and Naturalists comprehend the site from a dimension of full nature, considering mostly the nature as it was in its origin.

Ecology’s principles and vision of the Natural Landscape refer to the ancient times, and all transformation is perceived as a threat.

We have heard many times concepts such as: manmade projects have a great impact against nature because they permanently alter biodiversity; biodiversity corridors must be only natural; projects should only use native species; nature must be respected as original; production of goods and food produces harm nature. In many ways, they are correct and true ideas, but they may fall in an extreme interpretation.

This, we believe, is the trigger of the opposite positions between ecologists and landscape architects.

So, today more than ever, it is imperative that we find an understanding.

The nature in cities is composed by tangible and intangible elements such as natural traces; its history, culture, rites, myths, monuments, and buildings; natured and artificial spaces; and its biodiversity. They are inherent to cities and their landscapes.

Soil, water, air, vegetation, life in all its forms and other protagonists of the natural systems coexist with the anthropic systems in the context of the three spatial dimensions plus the variable of “time”.

It is in cities where people live, devise, realize, and grow, forging their history and values in ways that are intertwined with the public space. In this way, the natural and the social are inseparable.

Our space, the one where our house lies, is the very planet earth.

Today, cities are more inhabited and densified. A recent study shows that these days 50 percent of the world population inhabits cities, and it is estimated that this proportion will grow dramatically.

It goes without saying that without proper planning, the clear division between the rural and the urban will become blurred, due to the proliferation of new developments.

Thus, Urban Landscape is a living organism in a delicate evolutionary (or disruptive) balance.

Over the years, nature awareness and knowledge applied to landscape architecture has been varying. Studying it from a new and different perspective has substantially modified the related design principles:

Projecting in a more sensible way, we must increase the use of approaches that relate nature to the built environment. This provides a different view of the construction of the landscape.

Sustainability principles are a priority when dealing with landscape projects. Side by side collaboration is required between the different disciplines.

It is our mission to make Landscape Architecture a discipline of integration. The creation of sustainable projects can be achieved only by acting in coordination and direct relationship with other professionals and specialists such as Landscape Ecologists, Naturalists, Biologists, Sociologists, Cartographers, Geologists, Surveyors, Planners, Architects, Engineers, and Artists.

The challenge is to consolidate and unite criteria among these disciplines, in order to generate new ideas, to enable the growth and continuity of nature systems in today’s cities and in the “cities to come”.

about the writer

Jürgen Breuste

Dr. Jürgen Breuste is Head of the working group Urban and Landscape Ecology at the University of Salzburg, and founding President of the Society for Urban Ecology (SURE).

Jürgen Breuste

The subject “How can we get landscape architecture and ecology better integrated in the service of better cities?” is really important. It is important to bring all possible partners and activities for this target of “creating better cities” together. This aim requires even more partners than ecologists and landscape architects. But these two disciplines can be seen as core disciplines for reaching the target.

By taking an ecosystem service approach, urban ecology and landscape architecture can cooperate.

These disciplines are often labeled “basic” knowledge (ecology) and “applied” knowledge (landscape architecture). This is right, but things are not always so clear cut, because ecology has already developed in the direction of application, and landscape architecture in creating new knowledge needed for architectural applications.

What we need is knowledge about the urban ecosystem, its functionally, processes, and structure. Without knowledge, all design is based only on ideas, fashions, or individual perspectives. But knowledge alone is not enough. We can see that only a part of the existing and available knowledge is used in planning and design of new buildings, new open spaces, new districts, and new or renewed cities. The actual visual example is the fast ongoing urban development of Chinese cities; this development is mostly not based on ecological principles and does not apply urban ecological knowledge.

Urban ecological knowledge includes not only knowledge from the natural sciences’, but also knowledge about those who design, develop, and use the urban ecosystems: the urban dwellers. For this, we definitely must integrate social science knowledge.

To apply ecological knowledge, a perspective of what is necessary to create better cities is useful. Any general goal has to break down to clear targets, measurable by indicators; only then can we make better designs. This is perhaps the rarest profession in the chain, from knowledge-gathering to change-of-reality. A lack of policymakers causes even the best ecological designs not to be realized. All contemporary Chinese building projects have green roofs in the designs, but mostly none will be realized.

Flip sides of the same coin—one target

Ecology and landscape architecture seem simply to be flip sides of the same coin: both aim to make better cities. But this is not completely right. Ecology, as a university discipline, can successfully create new knowledge. Landscape architecture as a university discipline is forced to use knowledge for practical design solutions to problems. But both disciplines can work on both sides, the knowledge and the application sides.

Both urban ecologists and landscape architects aim to help develop natural environments that are “good for both people and nature”. But it is good to accept that the urban environment should be a natural environment, but one that is predominately designed for people! We should not aim to protect biodiversity or, more simply, rare species as assiduously in cities as we do with nature protection outside of cities for ethical reasons. We need a paradigm shift towards considering the whole range of urban ecosystems and towards the benefits we need from nature in cities for their inhabitants. Nature conservation may be challenged by the novelty of some urban ecosystems. But it is necessary to recognize the associated ecosystem services and social benefits of novel urban ecosystems, too. With this ecosystem service approach, urban ecology and landscape architecture can cooperate well and bridge the gap from understanding to making use of urban ecosystems.

Two key ideas of urban ecology

The most important critical idea that remains in urban ecology is to simply understand the ecosystems in a city or the complex urban ecosystem as a whole. With understanding, we follow the idea of modeling and balancing, which is ambiguous, especially when humans and human behavior are included. This is not an intellectual game, but a necessity for the next step, planning, and design of urban ecosystems. Landscape architects are typically better than urban ecologists at this kind of thinking. But we are best when we cooperate.

about the writer

Ana Faggi

Ana Faggi graduated in agricultural engineering, and has a Ph.D. in Forest Science, she is currently Dean of the Engineer Faculty (Flores University, Argentina). Her main research interests are in Urban Ecology and Ecological Restoration.

Ana Faggi

Although ecologists and landscape architects have shared many values they have often not, until recently, succeeded in reconciling important aspects in their shared projects, and that’s what causes many projects to fail. I think that this difficulty is anchored in the roots of both professions and by the way they have been developed so far.

The need to re-nature the urban matrix, making it more livable and sustainable, will not allow professionals to put design before ecological functionality anymore.

Ecologists are aware, and often carry the burden, of the complexity of any ecosystems they intend to restore or rehabilitate, while designers, in their day-to-day work, plan and fashion the form and structure of objects. When the object to be planned is a landscape, designers frequently threaten nature by neglecting the fact that creating green infrastructure is about designing autogenic (or self-regenerative) systems.

An ecologist working on a restoration project, in contrast, moves in hesitation, knowing of the hopelessness of an ecological landscape created by a designer; only Nature itself can do this. Nevertheless, the act of creating is central to the designer’s work; thus, landscape architects often approach a project by giving more weight to aesthetic and human aspects at the expense of ecological responsiveness.

However, this divergence is changing, and I trust it will change radically in the future. The need to re-nature the urban matrix, making it more livable and sustainable, will not allow professionals to put design before ecological functionality anymore.

Beyond collaborative thinking processes that presently prevail in any given project, smart city planning should move away from merging approaches or struggling to balance ecologists and designers in their traditional domains. A smart city needs doers trained in transdisciplinary knowledge at early stages of their academic studies. Transdisciplinarity arises when participating experts interact in an open dialogue, giving equal weight to each perspective and relating them to each other.

To decrease the present divergence between ecologists and architects, higher education should engage in curricular transformations. Evidence shows that different academic subjects and forms of curricula organization produce different kinds of people because disciplines involve clear world views and values. Therefore, universities, as key institutions in processes of change and innovation, should reassess what gets taught and researched and the way they train skilled labor forces. Professors and students should be involved in transdisciplinary long-term projects exploring ways of engagement with their communities.

For six years and with these goals in mind, the architecture and environmental engineering faculties at the Flores University, Buenos Aires, have offered students of both disciplines the opportunity to enroll in Landscape Ecology and Alternative Energy courses, where they work together and take part in ecological restoration and rehabilitation of public space projects (see photos).

about the writer

Susannah Drake

Susannah C. Drake FAIA FASLA is a Principal at Sasaki and founder of DLANDstudio. Susannah lectures globally about resilient urban design and has taught at Harvard, IIT, and the Cooper Union among others. Her award-winning work is consistently at the forefront of urban climate adaptation innovation. Most recently “From Redlining to Blue Zoning: Equity and Environmental Risk, Liberty City, Miami 2100,” was included in the 2023 Venice Biennale. Her first book “Gowanus Sponge Park,” was published by Park Books in 2024. Her work is in the permanent collection of MoMA.

Susannah Drake

Large, interdisciplinary consultant teams have become the norm in urban design over the last 20 years. The movement away from a purely formal, architect-driven vision of city making reflects a shift in understanding away from the primacy of a modernist position which uncoupled form and environmental process.

The landscape architect can synthesize the work of many disciplines and integrate myriad voices into a clear unified vision. But design has sometimes been lost.

In an essay titled “Regenerating Landscape Architecture” published in Topos 71 in 2010, I suggested that one of the reasons landscape architecture waned as a recognizable professional presence in the 60s and 70s was its merge with the discipline of ecology. Landscape architecture took on the mantle of environmental planning, a position that had a somewhat anti-urban focus. What resulted were large-scale planning efforts such as Ian McHarg’s layered analysis of Staten Island (see his book Design with Nature, 1969), which prefaced regional analysis over the urban human scale of design. The work, which ultimately led to the development of GIS mapping, remains a very important component of planning and mapping that should not be confused with design.

The formal backlash that occurred in the 80s and 90s is perhaps akin to the provocation hinted at in our prompt. While some designers remain purely aesthetically driven, others deny form, giving preferences to fish and mollusks over people. Happily, these camps are more at the fringe of the profession as a whole, which is now more rooted in a nuanced and hybrid approach that blends functional urban design, civic beauty, and viable ecological planning.

Collaboration between ecologists and designers is not without a lot of give and take. My firm DLANDstudio is currently working on a project for daylighting a stream with an engineer as the lead, an ecologist as designer of the stream bed, and DLAND—the landscape architect—as community liaison. The problem with this arrangement is that the landscape architect is tasked with explaining to the community why they will lose their programmed recreational space. The design is functional and will likely be beautiful, and will work well as a daylit stream, but denies the complex program requirement of a public park located in a dense urban center. If the landscape architect were leading the team, elements of program, ecology, community engagement, and civil and structural engineering would be more synthetically managed and prioritized. It is not an issue of form over function. It is an issue of finding a balance of form and function. The landscape architect is better able to synthesize the work of many disciplines and integrate myriad voices into a clear unified vision. Civic beauty comes from maximizing the potential of both natural and formal systems.

about the writer

Kevin Sloan

Kevin Sloan, ASLA, RLA is a landscape architect, writer and professor. The work of his professional practice, Kevin Sloan Studio in Dallas, Texas, has been nationally and internationally recognized.

Kevin Sloan

Facts and Ideas

Well, it may surprise the panel, but my private practice in landscape architecture and planning, Kevin Sloan Studio, consistently enjoys energetic and positive collaborations with ecologists, environmental engineers, and, on occasion, scientists. The reason our design work “reaches across the aisle”, I suspect, originates from a particular design view that was taught to me by two great mentors.

“Facts and Ideas”: when landscape architecture is seen ONLY as art, problems arise.

Werner Seligman was a young European architect in the mid-1950s who was hired and implanted into the School of Architecture at the University of Texas-Austin, along with a group of other European educators, to pioneer a new architectural curriculum for the 20th century. While Edward M. Baum wasn’t one of the “Texas Rangers” (a nickname given later to the UT-Austin Europeans), he was an academic colleague of Seligman’s and the Dean at the UT-Arlington School of Architecture. When I relocated from New York to North Texas, Werner told me to “look up Ed Baum”. What they both gave me was a “new set of eyes,” especially about how to see and understand the task of design and how it interacts with many other hands.

Architects and landscape architects bring facts and ideas together to direct the production of places and spaces. The “facts” of a project can include the specific needs of a location, a finite budget in money and time and/or the facts of horticulture and the climate of a particular region. Other facts might include lessons drawn from the great reservoir of history to imbue a contemporary assignment with content and depth. Then there are ideas, such as organizing principles, conceptual frameworks, patterns, theories, and metaphors that guide a landscape architect to artfully imagine possibilities that reconcile the facts and their problems.

When landscape architecture is seen ONLY as art, problems arise, potentially when they are working in collaboration with other fact-driven disciplines, such as ecology.

The work of an artist is treasured because it offers a personal and singular view of the world. Since ecology, and other related disciplines, such as horticulture and botany, are based on science and repeatable phenomena, the priorities of an artist can, on occasion, be exclusive and intolerable to the pragmatism of those who speak for nature, ecology and science.

In addition to facts and ideas, the design work of Kevin Sloan Studio aspires towards the standards set by great design precedents. One in particular, the round barn at Hancock Shaker Village in Massachusetts, is a unique and appropriate example for the roundtable because it demonstrates a perfect synthesis of landscape architecture, architecture, ecology, farming, and agriculture. When the round barn is fully understood, it’s difficult to assert whether it is a metaphor, a machine, an instrument, or something even more profound.

The Shakers clearly knew archetypes and architectural history, since the round form of the barn is not only temple-like, but is prominently located in the village as if it was in fact a place of worship. At the time, a round building was also the ideal form for feeding an entire herd of cattle using only a single farmhand. This was the functional objective.

When the farmhand would appear, the cattle would instinctively begin moving towards the barn where a round building was, again, a perfect form to face and gather the herd from all directions. Once they entered through a set of equidistantly spaced doors, the interior layout queued all the animals to vertical wood slats that lined an interior circular hallway.

The farmhand would then take a pitchfork of hay from the center mass and place it in front of the animal who was on the other side of the corridor—take three steps—then, repeat the process, around and around. Each animal left the queue when they were full. When the last animal walked out of the building, the herd was fed.

But the more profound aspect of the design is how it ultimately became a “time machine.” As political and religious separatists, the Shakers were a society devoted to energetic celebration. A barn that allowed them to feed the village herd with one brother would give the rest of the congregation a maximum amount of time for “shaking.”

Our office hopes that someday we will produce a design that is as effortless, brilliant, indestructible, and profound as the round barn at Hancock Shaker Village.

about the writer

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course on conserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and published a book, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

Mark Hostetler

Ecological Functionality vs. Aesthetics

In the realm of urban landscape design, ecologists (such as myself) frequently ask these conservation questions about a landscaping plan: Does it sequester/store carbon? Provide wildlife habitat? Filter water and improve water quality? Is it energy efficient and does it reduce C02 consumption? Provide opportunities for pollinators? Does it limit exotics and particularly invasive exotics? In summary, ecologists think in terms of ecological functionality or ecosystem services. Architects and landscape architects tend to think in terms of aesthetics and functional use by people: Is the landscape beautiful? Can people use and have a quality experience in the place?

Real ecological functionality needs to be, and can be, embedded in landscape design. And the public would be OK with that.

First, a recent blog by Kevin Sloan on a concept called “One Landscape” explores an idea where buildings and other hardscapes match natural elements such as trees, hedges, and lawns. In the design of suburban megacities, Sloan states “. . . the future will, in fact, be One Landscape where nature, either cultivated or ‘wild,’ co-exists with diffuse patterns of civilization that feather across density and nature layers”. Initially this sounded good to me, but what does this design concept mean? Loosely translated, this means where landscapes and buildings “reciprocate.” As an example, evenly spaced trees replicate the columns and walls of buildings (see illustrations in blog).

To me, the One Landscape concept is an example of a landscape architecture idea that lacks discussion about ecological functionality or ecosystem services. Taking the example above, planting trees in an even spaced line, particularly if they are the same exotic/ornamental species, is a disservice to biodiversity. A monoculture of exotic/ornamental trees is not good habitat for a variety of wildlife and insect species. Biodiversity thrives at the edges of and in the thick of “chaos.” Symmetrical and even designs limit biodiversity, not to mention what these highly maintained landscapes mean for energy consumption and water consumption. A more natural landscape requires much less maintenance and is better for wildlife. Overall, I would argue designing with such symmetry would not conserve natural resources and any “win-win” scenarios are lost between aesthetics and ecological functionality.

Next, Joan Iverson Nassauer’s original study on homeowner preferences proposed a concept called “cues to care.”. She presented homeowners with photos of yards varying from highly manicured to more natural in appearance, asking them what they thought about these yards. The take home message from the study results were: “They [results] suggest that to be publicly acceptable, ecological practices must be designed to pay special attention to vernacular cues to care. Design that maintains aesthetic quality should include prominent mown areas in front of patches of indigenous plants. As a general guideline, mown areas should cover at least half the front yard.”

This is a study of a suburban community in Minneapolis-St. Paul—and it is supposed to represent the entire U.S. culture? I have heard this study, which is relatively old and can be found only as a technical report, used as a rationale for having a landscape that is highly manicured. I argue that this study has been widely misinterpreted, and is not a representation of landscaping preferences among people living in the United States. The study and the interpretations of it are fundamentally flawed on several levels. First, it is a non-random sample of a small residential community in only one city—hardly a representative sample of most Americans (or even of Minneapolis-St. Paul). Second, the residential participants for this study (about 167 in total) had come from neighborhoods with highly manicured landscapes. It is inherently a biased sample. These participants already were exposed to a neighborhood “norm” of mowed lawns with little indigenous vegetation, so of course they would select manicured lawns as desirable. I wager that if homeowners were interviewed from a much older residential neighborhood that had little or no lawn, their opinions would be much different because the neighborhood norm is quite different. In this hypothetical example, I suspect results would be skewed more towards yards with less lawns (and more native vegetation) as more desirable. In this case, the “cues to care” may actually mean a more ecologically-minded yard with less lawn.

I have worked with a community in Gainesville, Florida, (called Madera) where mowed lawns actually stick out like a sore thumb. Native vegetation and a lack of mowed areas are the “norm.” I bet if we were to do the exact same study on this neighborhood, the results would be quite different and lawns would be less preferred. Perhaps starting off with a neighborhood design that minimizes the amount of lawn would create an initial norm that would carry into homeowner awareness and preference.

In summary, I think city/residential landscapes can be both aesthetically beautiful, functional for people, AND ecologically functional, providing many ecosystem services. I do understand the position that peoples’ values play a significant role in landscape design, but I think we need to revisit aesthetics and what actually are norms in different situations. We just need more examples of ecologists and landscape architects working together, and creating properties where the highly manicured portion of a city landscape becomes the smallest part of the landscape. If this came to pass, I believe residents would be much more accepting of “messy” landscapes that are more sustainable.

Peter Werner

Give urban biodiversity a chance!

Private and public green spaces and structures planned and designed by landscape architects have a main impact on the biological diversity of cities. Many landscape architects do a good job and plan and realize good, attractive, and ambitious urban green. But, from my view, I miss some essentials with respect to maintaining and improving urban biodiversity.

It is necessary that landscape architects grapple with scientific knowledge about urban biodiversity through education and collaboration with ecologists.

What is it that I miss? The landscape architects construct green areas, which show richly structured vegetation; the vegetation is aesthetic and it considers the needs of the people. Many of these landscape architects believe that they make a contribution to species richness and diversity, both quantitative and qualitative. As a rule, however, they use a superficial understanding of the meaning and mechanisms of what constitutes urban biodiversity, aligning it with visual perception. Those planning and designing do not realize that such an approach can realize the potential of a location for the protection and development of diversity and for the perception and experience of nature by the dwellers but, possibly, can counteract biological diversity. Some examples for the latter: if the construction material stone is used excessively in green places, even when stone is present in abundance in cities; if the extensive offer of flowers attracts pollinators, but the blossoms are modified or infertile, that pollination is not possible; if the landscape architects share the sentiment, without analysis, that wild places, like wastelands, are ugly and have no value.

I think it is necessary that landscape architects grapple with scientific knowledge about urban biodiversity. The responsibility for the protection and improvement of biological diversity should be become an integral part of the education and training of landscape architects and, in this context, they should be taught which processes influence biodiversity in urban areas.

Who of the landscape architects knows the essential components of the local and regional species pools? What are the biogeographically typical species, which can be part of the urban biodiversity in order to mirror the regional biogeography? How well do landscape architects know the impact of their planning and designs on the diversity of animals and plants? Which landscape architect is aware that each planned and designed green space influences the structure of the metapopulations in the city? Or, is aware of the contributions of the green space to the local food chain? Etc. etc. Experts in the local and regional species pools are not always able to present sufficient answers for the specific plan, but they can give an orientation.

And, another point. Do not forget common species. They contribute to regional identity, because the common species of the surrounding landscape are often species that are able to enter and survive in urban areas, too. They are also fundamental for the occurrence of rare species in urban areas, because they support the nutrition cycle, are essential parts of food webs, act as shelter for other species, and ensure a great extension of the ecosystem services. Last but not least, they provide the biggest potential for nature experience in urban areas.

Landscape architects make important contributions to the valuation of urban green. Therefore, they should visualize that apparently ugly places, such as wild, unpleasant waste areas settled by a variety of plants and animals, are of value. Good planning concepts and the placing of remarkable symbols, but also the use of interesting information, can produce a shift in thinking, such that the former ugly place becomes a new beauty.

What would be helpful?

First: The topic of urban biodiversity and the scientific background and knowledge of that topic should become an essential part of education and advanced training of landscape architects

Second: Local and regional knowledge by experts and laymen (citizen science) about the occurrence—in past and present—and diversity of species and their habitats should be considered in planning and design of urban green.

Third: Landscape architects are important stakeholders conveying awareness about values of green spaces and structures. Landscape architects, ecologists, and environmental economists should come together to discuss and work out the valuation and improvement of urban biodiversity.

about the writer

Anne Trumble

Anne Trumble is a landscape and urban designer based in Los Angeles, where she is currently working with the Arid Lands Institute.

Anne Trumble

I suspect most ecologists are well aware of the things I’d like to share about landscape architecture. Because you, ecologists, interact with the impacts of our work long after we’ve fulfilled a construction contract. How does the large plaza and pier on a new riverfront impact the river ecosystem ten years after the ribbon cutting ceremony? Ask an ecologist. How does a designed “forest” in a local park impact bird populations over time? Ask an ecologist.

Try as we might to act on behalf of all living creatures and systems, a landscape architect’s work is anthropocentric. It is shaped by human constructs: ownership of land, commodification of space, and human timescale.

Ownership of Land:

Landscape architects most commonly work for clients who own land. While natural systems and non-humans disregard these legal definitions of who owns what, we are bound by and to them. Water flows, soil is porous, and birds, animals, insects, and plants move fluidly across property boundaries, while we create islands according to them.

Try as we might to act on behalf of all living creatures and systems, a landscape architect’s work is anthropocentric.

Landscape architects are often asked to quantify how a project will increase capital, in order for it to happen. Metrics tell us that landscape architecture can raise surrounding property values, increase human health and productivity, reduce crime, and attract people who then support nearby businesses. Other less commodifiable value propositions, such as ecosystem health, are acceptable so long as they don’t decrease the commodification of a space; what keeps landscape architects employed.

Human Timescale:

Landscape architects plan and design with the goal of implementation. To implement a plan, we construct it, and to construct it, we have contracts to manage liability. Contracts operate on human time, which is usually about maximizing profits and often at odds with ecological time which is about maximizing change and resilience. The images we create to communicate with clients and the public represent contract time because they illustrate what a landscape will look like as a result of construction. Sometimes built landscapes get frozen in contract, or human, time because maintenance keeps them looking like the static images that convinced people to build them. As we’re learning from erratic and increased weather events, human time landscapes are less resilient than those with the ability to change with and adapt to a changing planet.

Ecologists, can you see how much we need you? You know how the islands of our work within property boundaries impact natural systems beyond. You know what is the highest ecological value we could embed into our commodified spaces. Now that we are in the Anthropocene, whereby humans are the greatest geologic force on the planet and nothing remains untouched by us, we need your feedback loops. Since we work on human time, and you on ecological time, we must put our heads together to bridge the two for more resilient communities, and planet.

about the writer

Christine Thuring

Christine Thuring is a plant ecologist who integrates her love of life into creative collaborations and educational dialogues. While her expertise is expressed particularly in the built environment (green roofs, living walls, habitat gardens), she is passionately practical and enjoys restoring peatlands, mentoring students, leading interpretive walks, and advocating sustainable and healthy lifestyles.

Christine Thuring

Yin and Yang: Urban Ecology and Landscape Architecture

Dear Landscape Architecture, We’ve been together for several years now, and they’ve been the most exciting, fruitful and creative years of my existence. As a team united by shared values and interests, we have combined our skills, perspectives and knowledge towards projects that are beautiful and functional, both ecologically and culturally.

One of my weaknesses, as an ecologist, is to get bogged down by the everything I don’t know. I could take a lesson in confidence from a landscape architect. Who, in turn, needs to get out from behind the computer screen.

Sadly, we are not in a balanced place at the moment. Our therapist, David Maddox, has suggested that we communicate our discontent and seek reconciliation by identifying the gaps between us. Specifically, he suggests we reflect on the following: How can we get landscape architecture and ecology better integrated in the service of better cities? After some venting, I will reflect on the inadequacies of my profession in this light and will conclude by outlining some approaches that, if we both adopted, could help create better cities and landscapes.

When we first got together, we used to go for vivid walks that elevated our powers of observation to child-like ecstasy. Do you remember? Whether in the natural environment, sculpture parks or beautiful cities, the outdoors is definitely where we fell in love, because we love the same things. Our poetry sang the praises of natural shapes and forms, admired the intricacies of blossoms, and mused upon dramatic contrasts. We were constantly learning from each other, and took turns exchanging field guides and sketch books. Or at least this is how I remember it.

Nowadays, you’re only ever behind your screen or at the drawing board and rarely come outside. It seems that you trust your notes and photographs to the extent that you don’t need to visit the site again. Working at plan view is such an abstract and technical exercise! I don’t want to challenge your practice, but I am concerned that you are limiting yourself (and your gifts of creativity and sensitivity) to a 1-dimensional plane. Is it time pressure/ time management? Or have you lost touch with your inspiration?

If there wasn’t so much at stake, I wouldn’t mind. But your studio-/ screen-based process also seems to have shifted your priorities away from “life” and increasingly towards “living”. You take such delight in geometry, sculpture, and clean surfaces that little time remains to consider other forms of life. What about birds and bats, who need homes, food and water? Given so little thought, designed features like lollipop trees will offer little benefit to particular species who need our help. Your colours and patterns are beautiful, but will the species lists actually benefit insects, pollinators, or birds? How will they affect local and regional food webs?

On the other hand, I really admire your ability to move forward on a project in spite of incomplete knowledge or understanding, as I realise this is a hindrance of mine. As a plant ecologist who dabbles in landscape design, I am hindered by my ideal to thoroughly know a site and to predict how an installation will establish and develop. One of my weaknesses, personally and professionally, is to get bogged down by the knowledge of the knowledge I lack. I could take lessons in confidence from you, since my holding back does not serve the world.

I have faith in our connection, and believe that we can accomplish much more together than we could alone. Following are a few points that I think could help create better cities and landscapes. These may resonate with you, but perhaps with other professions, too. At the very least, I hope they help us better understand each other and our relationship to making the world a better place.

The urban ecologists approach to landscape design:

- Observation: prioritise observing the site (or other sites with similar qualities) at various times (day/ month/ year);

- Consequential yields: plant selections will impact food webs and trophic structures, so choose your plants wisely;

- Bird’s-eye view: consider the role of the site/ project to regional corridors, networks, populations, communities, etc.

- Think global, act local: identify local qualities and features that are relevant to the site and its context (e.g., cultural heritage, green space networks)

- 80-20: aim to spend 80% of your time/ energy on the survey, analysis and design, and 20% on the implementation and maintenance;

- Ethics: regenerative and sustainable designs can be achieved when they take into account the needs of local communities and people, the potential of local ecosystems, and create conditions for abundance;

- Patterns: design from patterns to details;

- Collaborate: there is always more to learn (and it’s fun!);

- Stay informed: science and practice continue to churn out valuable information and knowledge;

- Down-to-earth: if you start feeling overly conceptual, get outside and refresh.

about the writer

Danielle Dagenais

Associate Professor, School of Urban Planning and Landscape Architecture, Université de Montreal B.Sc. Agriculture, M.Sc.A., Environmental Engineering, Ph.D., Environmental Design Research: Phytotechnology, Stormwater Management, Urban Biodiversity

Danielle Dagenais

In our part of Canada, ecologists have been leaving the “pristine” forests of the North for the cities, first invading their conservation areas and more recently their inner cores. Is this migration the result of an epiphany, a road to Damascus, or just an opportunistic change in habitat due to the gradual extinction of funding resources in the natural range of that species? One can only guess.

Ecologists are now, more or less reluctantly, calling upon landscape architects and planners to join their teams: as partners, or as wallflowers. Can genuine hybridization occur?

Anyway, the result is that the urban jungle now gets the attention of ecologists. They are slowly realizing that the key species in that strange built environment is man, and humans have strange views on nature. In fact, they don’t always appreciate it or recognize the true value of biodiversity. To contend with this challenging urban environment and win over urban communities, ecologists are now, more or less reluctantly, calling upon landscape architects and planners to join their teams: as partners, or as wallflowers.

For example, ecologists might deploy heavy modelling artillery to plan green infrastructure considering target species. Or they will go to great lengths to study the ecological dynamics of urban forests or wastelands. Or they’ll decide to conserve a piece of remnant nature. At first, the city and its inhabitants are not taken into account. After a while, landscape architects and urban planners are invited to join in, out of caution or to put a qualitative or aesthetic finish on the project. However, the question or the project is already framed within a very narrow ecological perspective. Important issues such as people’s perception, appreciation, valuation and uses of urban nature, not to mention social acceptability, are neglected. Co-design was never part of the plan. Had landscape architects participated in the definition of the project or the construction of the research object from the start, the collaboration would have had a better chance of success.

Are ecologists entirely to blame? Interdisciplinary research is hardly the norm, even today. Funding agencies and universities are partly responsible for the state of affairs. In Canada, at least, funding agencies are still divided between Health, Natural and Applied Science, and Social Sciences. And in this age of meagre funding, competition between disciplines is fierce. Any project on the margins, any hybrid that may possibly be funded by another granting organization, is viewed with suspicion. In universities, education in biology and ecology is still heavily, if not solely, focused on the natural environment, both at the undergraduate and graduate level. Students have very little chance to acquire basic social science or planning and design notions. Yet I often see ecology students who work on urban sites and are eager to integrate a social, design, or urban planning aspect into their graduate research. But the format of graduate studies in ecology and sciences in general and the productivity expected from universities precludes the students from taking the time to acquire the necessary knowledge to venture outside of their field or to work with a colleague from another discipline.

Studies suggest that encountering nature is important both for children’s development and their connectedness to nature. Isn’t time that ecologists encounter landscape architecture and planning earlier in their education if we want successful connections to occur and better cities to be built?

about the writer

Nina-Marie Lister

Nina-Marie Lister is Graduate Program Director and Associate Professor in the School of Urban + Regional Planning at Ryerson University in Toronto.

Nina-Marie Lister

Ecology + Design: From Marriage (Therapy) to Music (Metaphor)

Our work here in the big chorus of TNOC centres on the intersection of cities and nature; both big, messy joyful cacophonies of life, teeming and pulsing with energy. Ecologists (and other environmental scientists) and landscape architects (along with planners, architects, and urban designers) are all focused on making and shaping healthy habitats—homes—for all. So why do our professions continue to compete rather than collaborate, or repel more than we attract? I wonder why in my professional world that acknowledges complexity, values diversity and embraces uncertainty, do we continue to struggle with both the concepts and the practices of synergy, integration, hybridity?

It is precisely within creative tension of multiple perspectives that we find the possibility and the promise of a more resilient, convivial future.

However, designers do rely on carefully honed powers of observation, and that is arguably poorly understood, in part because the design community hasn’t cultivated methodological scholarship or invested in it to the same depth and extent of the sciences. In methodology, designers often appear as poor cousins of the sciences. If scholarship doesn’t show it, the evidence of practice does: designers are indeed trained to finely-tune their observation skills for detailed, meticulous and technical representation—from the patience of photographing or sketching a tree though the seasons, to the dynamism of human life drawing, or animation. A designer’s observation abilities are reflected in technical skills (either by hand or computer) which are needed for adept visual communication; these abilities are built through repetition and experience, and are not unlike the rigour of or investment in an ecologist’s empirical training for systematic experimentation. The designer’s repertoire of observation is ultimately deployed as the springboard for inspiration, as a companion to intuition, and the pollinator for imagination that is essential to envision a desired future. In short, whether ecologist or a designer, we all value observation and narrative—the power to tell a story.

But we rely on different ways and scales of knowing, and we look in different directions: ecologists see what is, and designers see what could be. Both these perspectives—the objective and the subjective, the normative and the conditional—are fundamental to creating a shared story, and from this, making legible the landscapes we live in. These are not binary skills in competition, or singular in isolation. Rather, they are improved in collaboration and enhanced in creative tension. The paradox is that neither approach is especially useful in the work we do without the other!

Ecology, nature, environment, cities, all rest on the central notion of oikos, home; not merely a house, but a home, which implies a certain kind of bond, whether communal, familial, or just familiar. And like a home, (or as Steven Handel cheekily reminded us here, like a marriage), we know it is not a constant place of peace, love and harmony—there are times of dischord and dissonance, and others of comfortable resonance. The point is that there are many melodies possible. So maybe there is power in a music metaphor as well as marriage therapy! The nature of cities—like life itself—is a symphony: complex, diverse, and much more than the sum of its parts. We need our diversity of perspectives, integration of voices, and scales of observation, both dissonant and resonant. It is precisely within this creative tension that we find the possibility and the promise of a more resilient, convivial future—one in which we collectively honour both the culture and the nature that sustains us.

about the writer

Diane Pataki

Diane Pataki is a Professor of Biological Sciences, an Adjunct Professor of City & Metropolitan Planning, and Associate Vice President for Research at the University of Utah. She studies the role of urban landscaping and forestry in the socioecology of cities.]

Diane Pataki

Scientists today are worriers. These days, when we look into the future, more often than not, we wonder, “what will go wrong”? It wasn’t always like this; there was a time when, like designers, scientists wondered, “what if” and saw a magnificent world of possibilities for technology, for cities, and for the way that people might live in the coming decades.

More than just providing performance monitoring, scientists are hoping to work with landscape architects to test critical pieces of the urban ecosystem puzzle with every new project.

But things have changed after the many mistakes that have been made. Science and society have failed to anticipate the worst consequences of technological advances such as combustion engines, mass production, the widespread use of impervious surfaces, and modern highway systems. The result has been ever-increasing concentrations of pollutants, degraded water systems, cities clogged with traffic, and divided communities. We are seeing political and social ramifications of the dawn of the Internet age and social media, not all of which are positive. Our cities are dependent on massive imports of energy and materials, leading to waste products that have nowhere to go except into landfills and the local air and water supply.

Scientists worry so much, but design can help

There’s much hope that nature in cities can rectify some of these mistakes. If paving over large areas of land caused many of the environmental problems of the 20th century, won’t restoring nature reverse the trends? And yet, scientists worry about this solution, since we have miscalculated before. History has shown that the places we created are complex and dynamic. Cities are ecosystems and the great lesson of ecology is that most ecosystems are unpredictable: try to push them in one direction and they may take off in another. When we tried to fix the problem of urban infectious disease we created “sanitary” water conveyance systems that concentrated pollution; when we revitalized neighborhoods with new parks and amenities we displaced poorer residents through gentrification. In fact, the list of unanticipated consequences of large-scale programs to “fix” cities is perhaps rather longer than the list of anticipated consequences.

So we worry. Many people ask: what could go wrong in large-scale efforts to bring nature back to cities? Here are some of the issues that give us pause:

1) Scale: The simplest concern is that small scale greening projects are not up to the task of absorbing and mitigating the dramatic emissions of pollutants and other transformations of the urban environment. It’s likely that most green solutions to urban problems must be implemented on a very large spatial scale to really make an impact. But honestly, in most cases we don’t really know the scale that’s necessary to achieve the desired impact—that’s a fundamental knowledge gap. This shouldn’t prevent us from engaging in small-scale projects. However, to really solve critical urban problems, we must get a handle on scale and advocate for the right scale in the right place.

2) Altering systems that we don’t really understand: Large scale change comes with the possibility of making large-scale mistakes. Neither science nor society has a great track record of reliably predicting the outcome of dramatic land transformations. I live in a desert city, and worry in particular about water resources and climatic consequences of efforts to shift vegetation and greenspace in one direction or another. Desert cities in the U.S. tend to use quite a lot of water to manage urban greenspace. It’s a worthy goal to reduce this water consumption, but many other ecosystem components are tied to water including local climate, human thermal comfort, energy use, and downstream water supplies such as groundwater. When we consider changing one part of the system, we must carefully consider possible cascading effects.

3) The right project for the right place: This is an old axiom, and yet, the devil is in the details. I have found that ecologists and landscape architects have much to discuss about why and how particular projects are suitable for a particular city, landscape, and site. In my city, located in a unique high desert region, there is much discussion about what a climate appropriate landscape looks like, and how it might provide needed shade and aesthetic properties while minimizing water and maintenance requirements. Which imported design types work here? Which plant types balance resource use, aesthetic, and functional criteria? Why or why not? There is still much discussion, a few points of agreement, and many uncertainties.

The scientific tendency to focus on uncertainty can be frustrating for people who need to act now. As scientists, we don’t want action to grind to a halt just because we don’t know all the answers yet—far from it. But as a compromise, we propose to build uncertainty into action. This can be done with projects that are “safe to fail” and by providing mechanisms to plug knowledge gaps with each new design project. More than just providing performance monitoring, scientists are hoping for opportunities to work with landscape architects to test critical pieces of the urban ecosystem puzzle with every new project. In many cases, we know what we don’t know, or at least can take a good guess. Can we build projects together that fill the many holes in our understanding of how cities work? This might make the future of cities much more predictable, with fewer mistakes and consequences that we can more fully anticipate. We might worry a lot less, and together start imagining again a great future full of new possibilities.

about the writer

Mike Wells

Dr Mike Wells FCIEEM is a published ecological consultant ecologist, ecourbanist and green infrastructure specialist with a global outlook and portfolio of projects.

Mike Wells

Disciplinary myopia and professional tribalism

The question is a vital one, but just one example of a wider phenomenon and problem related to design in its entirety, that of “disciplinary myopia”.