In a recent essay on TNOC regarding urban inequality, I spoke about the need to address inequality in exposure and vulnerability of urban populations to risk as a necessary condition to reducing urban inequality in general, including inequality in the access to basic services.

I would like to expand on this idea by underlining the need for good governance in order to reduce urban inequality. When talking about good governance, attention is often directed, legitimately, at addressing governance deficits at the urban, local, and national levels. Notwithstanding the importance of the above, we also need to examine governance deficits at the corporate and international levels.

Relieving urban inequality in exposure and vulnerability to disasters requires good corporate governance

For example, in many cities in the “developing” world that suffer from weak national and urban governance, the United Nations and other international aid agencies often employ the help of international consulting companies to develop urban master plans for Disaster Risk Management (or DRM) and resilience. However, these master plans often end up not being implemented because the best practices and good governance principles reflected within them challenge vested interests at the local and national levels. This often puts pressure on consultancies and aid agencies to align the recommendations with local authorities’ interests, while keeping contradictions with best practices to a minimum. Although this compromise meets the immediate “shareholder interests” of consultancies and aid agencies, it does not necessarily reflect the “stakeholders’ interests”, where the latter actually means the urban populations living in the city under consideration.

In order to rationalize this compromise, and perhaps even trade-offs between shareholders’ and stakeholders’ interests, we need to develop good risk governance principles and guidelines for corporate risk governance. Indeed, it is not sufficient to blame lack of progress on weak governance practices at the local and national level. The scrutiny, and guidelines, must extend to corporate and aid-agency practices. The remainder of this essay provide examples of what these guidelines may contain.

Methodology for examining governance deficits

Before we develop guidelines and assessments for corporate good governance, we need to examine the existing tools that are available for analysing governance—and risk governance in particular—and apply these to the analysis of risk governance deficits at the urban level. Two available tools are the risk governance framework and associated risk governance deficits developed by the International Risk Governance Council.

In an earlier essay on urban risk, I identified risk governance gaps under relevant risk management guidelines, including: institutional, science-policy interface, risk pre-assessment, technical and societal risk appraisal, risk evaluation, risk reduction, data loss collation and analysis practices, recovery, etc. In this essay, the aim is to elaborate the above analysis and identify potential governance deficits and pitfalls at the corporate consultancy level, and then identify the required type of guidance and guidelines in order to avoid these pitfalls.

Case 1: Decision making process to upgrade poor urban neighborhoods against disaster risk

- Description of Intervention: Often during urban DRM projects, a decision needs to be taken on whether to update poor neighborhoods with weak infrastructure and old housing. In some instances, this is dismissed as not being feasible or cost effective, without giving due consideration to international best practices and lessons learnt from various interventions.

- Risk governance deficits:

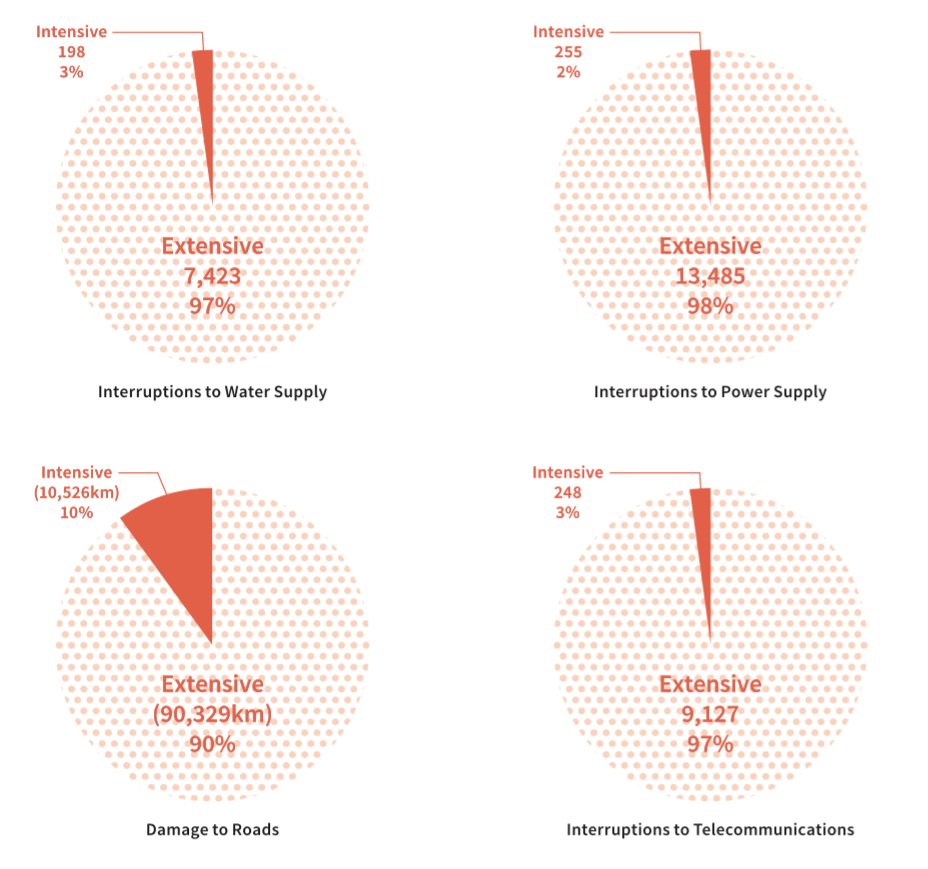

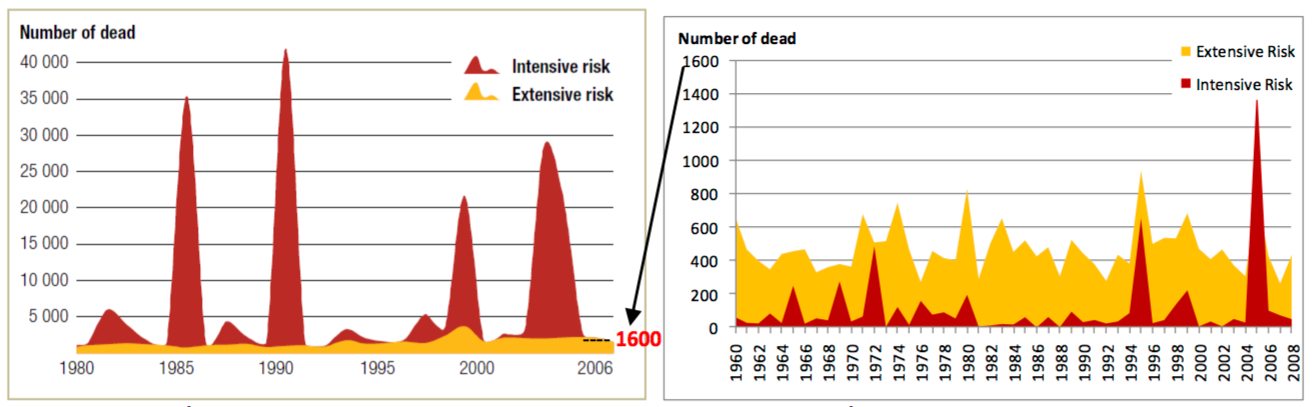

- (i) extensive risk (low intensity and high frequency), such as annual flash-floods and storms, are ignored and effort is directed at intensive risk (high intensity and low frequency), thereby automatically disadvantaging poorer neighborhoods, which disproportionately suffer from extensive risk;

- (ii) the benefits of saving lives is not accounted for in cost-benefit analysis, thereby automatically favoring richer neighborhoods, which have a concentration of newer infrastructure, assets, and investments;

- (iii) investments in the reduction of damages against extensive risk, usually in poorer neighborhoods with older infrastructure and housing stocks, is not considered, even though worldwide evidence shows this is cost-effective;

- (iv) disaster losses due to extensive risk are not estimated, albeit qualitatively, to make a case for investments;

- (v) financial needs and potential sources of funding from both the public and private sector are not assessed prior to dismissing the option of reducing existing risk in poorer neighborhoods; and

- (vi) multi-year implementation programs are not developed based on financial needs and available sources of funding.

Case 2: Upgrading of coastal urban neighborhoods against tsunami risk

- Description of Intervention: Coastal neighborhoods facing tsunami threats have various options for improving their preparedness against tsunamis. These options, ranging from physical defenses to early warning systems and evacuation plans, can be adopted individually, or in combination. The eventual decision does not always ensure that the most vulnerable communities and households will benefit from the interventions.

- Risk governance deficits:

- (i) evacuation plans do not account for the needs and capacities of the population, and how they vary with age, sex, ability, health situation, and general socio-economic conditions;

- (ii) early warning systems do not reach the most vulnerable communities;

- (iii) evacuation and response plans are neither based on, nor informed by, multi-hazard risk assessments;

- (iv) Investments in tsunami physical defenses are not compared against, or coupled with, early warning systems and response and evacuation plans; and

- (v) investments in tsunami physical defenses are not compared against, or coupled with, a cost-benefit perspective against investments in reducing extensive risk.

Case 3: Urban master plans against disaster risk

- Description of Intervention: Usually, large international consultancies develop master plans for local authorities for general resilience building and /or for mono-hazard management (e.g. earthquake master plans).

- Risk governance deficits:

- (i) consultants are not sufficiently informed by existing socio-economic constraints, challenges, and opportunities, as identified by various studies;

- (ii) analysis is not sufficiently informed by disaster loss data;

- (iii) method of analysis was originally developed for advanced countries and assumes the availability of accurate spatially and socio-economically dis-aggregated data. Effort is not sufficiently directed at tailoring the prospective plan to the current level of data;

- (iv). the large degree of uncertainty in hazard frequency and intensity, and in its impact due to the lack of data, does not trigger a recommendation for a more participatory approach, specifically to address the large degree of uncertainty;

- (v) the recommendations are not sufficiently informed by the current science policy interface, and as such will not lead to an improvement in this interface; and

- (vi) financial, governance, and sustainability challenges in implementation are not sufficiently accounted for.

A way forward

DRM and resilience practitioners need to develop guidance for improving risk governance at each of the stages of the risk governance framework. The guidance will only be meaningful if its implementation by consultancies is adopted by independent bodies to safeguard the interests of the stakeholders. The guidelines can take the form of a checklist, which facilitates auditing by external civil society bodies and networks. An example is provided below on a typical checklist to be used during the Risk Pre-Assessment Stage; a concerted effort is required to produce checklists during all stages of the decision making process.

Checklist for auditing risk governance Stage 1: Risk Pre-Assessment

During the risk pre-assessment stage, the following decisions are usually made:

- The scope of the risks that will be studied is determined.

- The methodology to be used in the analysis will be determined.

- The scope of interventions (ranging from risk prevention to risk mitigation to response and recovery).

- The degree of participation in the risk management methodology and its relationship to the degree of uncertainty in hazard and risk data is determined.

- The interaction between poverty and poverty reduction, and disaster risk and extensive disaster risk losses, in particular, is accounted for.

- International best practices and guidelines that may be useful and should be considered are laid out.

The following checklist is useful to audit the decisions regarding the above points.

- Has extensive risk been identified as part of the risks to be considered in the scope of risks? If not, has a justification been provided?

- Has the science-policy interface been assessed and has the result of this assessment informed the methodology to be used?

- Has risk reduction been considered as a possibility to be considered, subject to its feasibility?

- Has participation been identified as a tool to be increasingly used as the degree of uncertainty increases?

- Does the methodology aim to account for the interaction between disaster risk losses and poverty?

Fadi Hamdan

Beirut

First of all, congratulations on the development of this important topic. I also think that urban desiguladade has to be solved.