I read this article by Menno Schilthuizen, a Dutch evolutionary biologist and ecologist, about the evolution of animal and plant species taking place in cities. In cities, evolution is propelled by two forces: the known laws of ecology AND the social dynamics of human society.

The city habitat, as a novel ecosystem, promises a towering stack of current and future questions that cross disciplines.

The article concludes that we are witnessing the emergence of a novel, hybrid type of ecosystem, one that is emerging at different locations all around the world at more or less the same time: the urban ecosystem. This made me question: why are more and more species calling the city home, and how do they adapt to survive in this new habitat?

Let’s start with my own home and habitat: Amsterdam. The Netherlands is one of the world’s most densely built up and populated countries. There are very few places in this country where you will find a horizon free of man-made structures, complete silence (even in the 650,000 ha appointed as silence area, where noise levels should not exceed 40 dB, there is no guarantee that the rules of silence will be complied with), or a night sky lit solely by the moon and stars (actually, we’ve got only two such spots). You will have to get yourself to the coastal outskirts to find these extraordinary places; in the rest of the country, ecology and society bump into each other constantly.

In order to guide this eco-societal contact, we have traditionally isolated one from the other by creating nature conservation areas and limiting urban sprawl by building compact cities. Zoning policies are valuable for protecting the functioning of different stakes that exist in a region: nature, food production, housing, industry, and so forth. The downside of prioritizing one function per area is the risk that the landscape becomes a collection of isolated or thinly connected islands. I will illustrate this using the “island” of intensive agriculture as an example of an isolated landscape, and the wildlife corridor as an example of a way to connect the “islands” of protected areas.

Large-scale intensive agriculture leads to impoverishment of the countryside’s natural character, chasing away birds and small animals that thrive on hedgerows and other linear elements that constitute the more traditional agricultural landscape in Europe. Removing grassy field margins and tree lines may obstruct water infiltration and increase erosion. At the same time, agricultural intensification and field enlargement lead to a decrease in the landscape’s attractiveness for tourism and outdoor recreation. People, just like other living creatures, enjoy variation in a landscape. So by prioritizing one function, in this case food production, there is a risk of losing other functions.

The second exemplary case is the wildlife crossing. The Dutch version of a wildlife crossing, the ecoduct, has become very popular over the past few years as an engineering solution for habitat fragmentation that connects natural areas with each other to enable safe animal crossings. And, as this video shows, wildlife crossings facilitate the movement of wildlife not only in Europe, but all over the world, including, for example, red crab migration in Australia. Yet since people are never far away, at least not in the Netherlands, the question has been raised whether to open wildlife crossings for recreational use. What would the deer, frogs, and hedgehogs think of sharing their crossing with hikers, bikers, and horseback riders?

Both cases illustrate a struggle between isolating versus mixing the diverse functions of the land. There is an ongoing debate about whether to propagate so-called nature-inclusive agriculture that offers opportunities for biodiversity increase through habitat creation—e.g., low-intensity management of drainage ditches that mimics natural processes. Farmers would receive financial compensation if they implement nature friendly measures. Then again, there is a strong argument against nature-inclusive agriculture: nature and large-scale agriculture have different demands on the land that are hard to satisfy simultaneously, such as in terms of the most preferred ground water level. So, in this case, ecology and society experience friction.

But the story is not just sad and gloomy. The bumping of ecology and society actually reveals very promising dynamics. And where do these dynamics reveal themselves most elegantly? In cities.

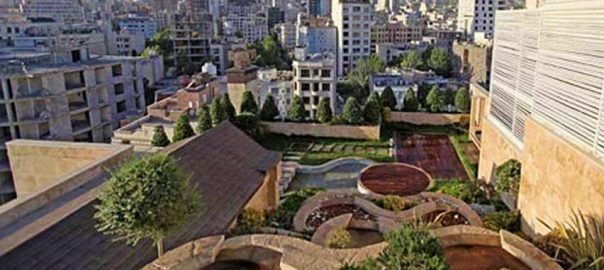

Because the city offers little space for isolation, functions need to be mixed. The city is a mix of buildings; infrastructure; flows of people, money and knowledge; but also home to an extremely diverse set of vegetation types and arrangements, water bodies, gardens, parks, and all things in between. The result is a unique ecosystem that operates on its own and that can only be expected to gain in importance, considering the increasing cover of urban land globally. Combined with the ongoing loss of natural habitat and the attraction of easily accessible food sources in the city, the emergence of the unique urban ecosystem has driven species formerly living in shaded forests and wild rivers to call this novel habitat home.

So, how do species adapt to urban living? Some are not so familiar yet with their new neighbors and remain on the lookout for spots with little human interference: the outskirts, industrial sites, and railway tracks. Amsterdam’s resident fox has built her hollow in a small patch of woodland right next to the train tracks and a large industrial area flanked by a busy road. Somehow, she manages to cross the road every day without getting hurt and with a meal for her family. On the menu: mostly rabbit (themselves once dumped here by their caretakers), alternated with the occasional rat or pigeon. A kingfisher has chosen to reside in one of the city’s port areas, a spot where the waters of river and sea collide to produce a large nutritional variety. From a sandy wall hidden by marshy bushes, the bird flies up and down while the ships go by. The grass snake has found a home in Amsterdam, too. It breeds in the urban forest, reproduces by the thousands, and the lucky few that are not turned into road kill or eaten by birds of prey can grow up to 100-110 cm long as adults. In March, these fellows like to go out in the sunshine, and you may very well find them sunbathing between the steamy stones of rail track levees—one of those urban fringes not crowded by people. If you’d like to see how the fox, kingfisher, and grass snake came to call the city home, the urban lives of these creatures have been beautifully captured in the 2015 documentary Amsterdam Wildlife, by city ecologist Martin Melchers.

Other species, birds in particular, seem to mind the presence of human beings to a far lesser extent. Amsterdam is full of swallows building their nests underneath the tiles of sloping roofs; I witnessed a coot trying to build its nest on a deserted boat in the canal in front of my apartment; and people have found blackbirds nesting on inner-city balconies, even when that space is shared with the owner’s pet. People’s presence can even increase an individual’s chance of survival, as shown in a scene from the documentary Amsterdam Wildlife. In one of Amsterdam’s few high-rises, an office of ABN AMRO bank at the Zuidas business district, or “Financial Mile”, employees took over the care of a young Peregrine Falcon after it was deserted by its parents. The bank employees even came in on weekends to feed the bird. Peregrine Falcons are Amsterdam’s penthouse inhabitants; they like heights and started to inhabit the city when tall chimneys and office towers were constructed. From their lofts—often man-made nest boxes—they’re living an easy life, just waiting for a pigeon to fly by below before dinner is served.

There are plenty more examples of animals adapting to city life. Madhusudan Katti recently described the growing population of endangered Kit Foxes in a California oil town in an article for TNOC. Matt Soniak has also provided entertaining stories about urban wildlife for Next City. In Chicago, for instance, coyotes have learned to navigate the city’s hectic traffic and can be found waiting patiently by the side of the road for traffic to stop, after which the coyotes start to make their way across. City coyotes in Chicago also appear to be healthier than their wild counterparts, as the city contains fewer of their predators and offers more food sources. Complex as they are, cities can turn out to be safer and steadier than many undeveloped areas. A severe drought in India that killed nearly half of the rural monkey population left Jodhpur’s city monkeys virtually unharmed. To other species, the urban heat island effect is what makes the city such an attractive place to live. Some insects just love the warmth, and this has resulted in more insects living inside than outside of cities. Meanwhile, people are purposely attracting biodiversity into the city. Residents actively plant flowers to attract pollinators and place bee hives on their green roofs, assisted and enthused by people and organizations trying to bring nature closer to the city.

So we know some of the reasons that animals come to the city, and have an idea of the ways in which they adapt their behavior to survive in their new homes. But does this adaptation also result in evolutionary changes? In his TNOC article, Madhusudan Katti mentions that Bakersfield’s Kit Foxes demonstrate novel traits. Also, some birds have adapted their singing to the urban environment. To deal with one of the largest urban burdens, low-frequency traffic noise, birds in San Francisco changed the tone of their melodies to a higher-pitched one. Or, they save their calls for the (relative) silence of the night. There are additional examples of typical urban bird behavior. Schilthuizen explains how, starting in 19th century Germany and extending from there to other European cities, blackbirds stopped migrating because cities offer plentiful food year round. In general, due to a lack of natural predators, urban birds are less sensitive to stress. This means that urban birds are evolving differently than birds of the same species that roam in non-urban areas. Research has shown that changes in urban bird behavior are taking place over decades, not millions and millions of years, and this process is labeled with the term HIREC: human-induced rapid evolutionary change.

Evolution-the-urban-way is happening all over the world. In a MOOC by Leiden University, Schilthuizen explains the effect on a species’ evolution if some reside in cities, facing strong selection pressure, and others of the same species don’t. Speciation may occur: the evolutionary splitting of a species into an urban and non-urban species. And if species evolve while in the city, how then do populations in different cities compare to each other? When the same evolutionary changes take place independently in different places or times, we arrive at what is called parallel evolution. These dynamics promise a towering stack of current and future questions for biologists and ecologists, but also for architects and planners (for a great example, see Mark Hostetler and colleagues’ new Building for Birds online tool), home owners and companies, food growers and traffic controllers. Most of all, these novel changes promise a chance to move from “nature despite people” and “nature for people” focuses all the way to a framework of “people and nature” that is underpinned by an interdisciplinary approach—just the right thing for our multi-function cities.

With the city habitat as a novel ecosystem, there is a whole new world to explore and discover for humans and, indeed, for many more animals.

Marthe Derkzen

Amsterdam

Leave a Reply