The first five people we spoke to in the San Anton neighborhood of the Mexican city of Cuernavaca didn’t know the location of the Salto Chico (small waterfall).

The neighborhood’s larger waterfall, referred to as the Salto Grande or Salto San Anton, is known as a place to buy ceramic planters originally made from the local clay. A small effort is made to promote the waterfall and surrounding basalt formations to tourists.

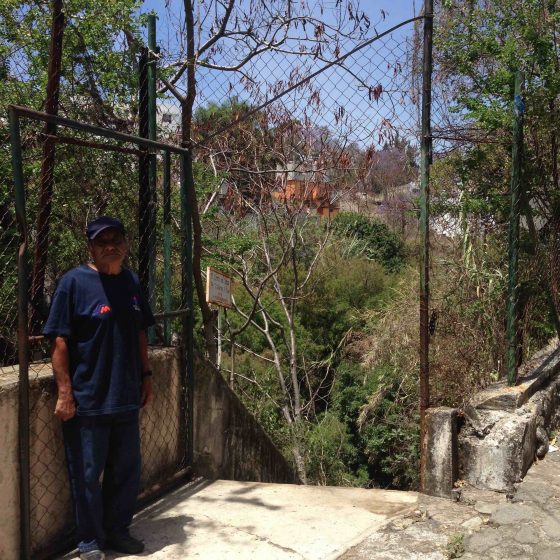

The existence of the Salto Chico, however, only seems to be common knowledge among people who live a five-minute walk or less from it. Passing through a barely visible entrance off a narrow street, it is a surprise to discover that the Salto Chico boasts its own stunning waterfall and basalt columns. The decaying infrastructure of walkways, terraces, and hanging bridges indicates that it was once an attraction. How is it that such a place in the middle of a densely populated city has disappeared from the mental maps of residents? How has a place of such beauty become a dumping ground?

At some points, we must wade through garbage to move around a waterfall-fed basin still recognizable as the sort of iconic bathing pool associated with ecotourism and natural shampoo. The gate at the top of the stone stairs descending down into the ravine or barranca generally remains padlocked, and most people don’t care because the Salto Chico de San Anton is understood to be a polluted place where no one would wish to go.

The situation of the Salto Chico echoes that of most of the barrancas that have historically defined Cuernavaca. Known as “the city of eternal spring”, its pleasant climate is attributed to the cooling effect of its 46 ravines, which have a combined length of about 140 kms and run through all parts of the city (Alvarado Rosas & Di Castro Stringher, 2013).

In April 2016, as residents complained about the intense heat, the barrancas seemed to have lost their moderating influence. As Pedro Güereca García suggested during his presentation that same month at the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos: the city of eternal spring has become the city of sewage drainage. At the Salto Chico, clean water from a spring mixes in with sewage from the houses of both the rich at the top and the poor clinging perilously to the sides of the ravine. Mechanics’ workshops add used oil to this sullied water, and other substances from various other sources are also incorporated—which is what happens in a place that belongs to nobody, explains César Salcedo, who is one of the people who does care deeply about the Salto Chico.

Cuernavaca’s barrancas are also the connective tissue of the Chichinautzin biological corridor, in which the city is situated. They have traditionally helped sustain the Corridor’s high levels of biodiversity by allowing plant and animal species to both survive in and pass through a dense and expanding urban area.

The barrancas have provided connectivity for people, as well. Friends tell me stories of walking to school through the barrancas so that the daily commute became an adventure. They often conclude with a sigh as they think about how such experiences have been lost to their own children—a common narrative in much of the world. But even without the great transformation of the experience of childhood, Cuernavaca’s barrancas are no longer very attractive to children or anyone else. As another engaged citizen, Javier Ballasteros describes: “These rocks were formed over thousands of years, but people born since 1980 have no experience of the barrancas. They don’t know this place. Maybe they walk by or pass by here in the bus or in their car. We swam and played here all day. Families came on Sundays. That was 50 years ago. We’ve destroyed it in 50 years…I bring my grandchildren but they want to leave. They say: ‘Everything’s dirty and locked up, we can’t swim.’”

In addition to the considerable contribution of garbage and sewage made by the general public, the municipal government proposed in 2007 to turn a section of the barranca of San Anton (near the aforementioned waterfalls and in the middle of a densely populated neighborhood) into a landfill site. This was a perceived solution to the closure of the existing dump outside the city—thanks to a roadblock erected by fed-up local residents. After much protest by civil society organizations, the idea of formally turning the city’s greatest asset into a dump was dropped. However, the propaganda that accompanied the lengthy promotion of the project served to reinforce an image of the barrancas as places best suited to receiving waste.

The presence of so much waste in places of natural beauty is a strange phenomenon. I began seriously thinking about it in 1983, during my first stay in Cuernavaca when a fellow passenger threw a bottle from a car window into a beautiful landscape. When I remonstrated with him, he proclaimed proudly: “Mexico is free!”

That moment has come back to me often and I still don’t really understand it. At that time, there was very little garbage in Mexico because there was little that was disposable—and most people wanted the deposit back on their bottles. I have been watching trash accumulate ever since in Mexico, in the U.K., and in various other parts of the world. My bewilderment reached a peak in 2007 in Honduras, when I discovered that a day out at the beach was like a day at the dump. Family picnics involved dozens of items in individual packets and the packaging would pile up around the picnickers as the meal proceeded. Late arrivals had to clear a space to sit before adding their own garbage. I was shocked—this was before I was familiar with the aftermath of sunny days in Manchester parks.

I really began to wonder if people saw garbage differently than I did, if they found the multi-colored packaging attractive, or their ability to purchase the packaged items as a sign of affluence. Or if, like the bottle thrower, they were perhaps pleased to be getting away with something, with not following the rules—which resonates in the context of the once rule-bound English parks, where resident park keepers even had the authority to lock up miscreants over night (Ruff, 2000). Or perhaps some people don’t even see the garbage—and don’t care if they add to it. Other species don’t necessarily care, either, as a key actor in looking after Manchester’s nature described: “We were standing on a small bridge and a heron landed on a shopping trolley in the stream, and you know shopping trolleys are not a problem, they can be a habitat just like any other. It’s only us that have a problem with shopping trolleys.”

The witness to the heron on the shopping cart and I agree, however, that it is extremely important that people connect with urban nature, and that a lot of people do mind if places look uncared for. To many such people—potential stewards of urban nature—wilder versions of urban nature look unkempt. Uncontrolled environments, such as “urban wildscapes”, i.e. “urban spaces where natural as opposed to human agency appears to be shaping the land” make some people very uncomfortable (Jorgensen, 2011, p. 1). They are seen as wastelands to which it is appropriate to add more waste. This means that although urban wildscapes are important places for some people (see Jorgensen, 2011) and for reappropration by other species, it is important for a significant portion of urban nature to show signs of care and to invite people into them (as I discussed in an earlier essay). At a minimum, people should not be met with locked gates.

Locked gates and garbage can make extraordinary urban landscapes, where nature could be at its most visible and interesting, become undervalued and, eventually, almost forgotten.

But things are changing in the hidden landscapes of Cuernavaca in part through the leadership of people who have cherished childhood memories of the barrancas and want to pass their attachment on to the next generations: “It’s about the grandchildren”, several of them tell me—and about engaging youth in the process of transformation. Nearing the end of our quest to find the Salto Chico and now in close proximity to it, a women points us in the right direction before we can even voice our question.

Descending the steps, we see the hundred or so people who have got there before us and already started work. “I don’t know if we’ll get it all cleaned up today,” says César, who is playing an organizing role while insisting that it is not an initiative of any particular group, but of civil society in general. I share his assessment as I survey the scene, noting that some sections of the path passing under the waterfall are buried under more than a foot of waste. However, within a few hours, the place has been completely transformed by dozens of mainly 20-somethings, with a complement of the older people who had played there as children, and of children who perhaps hope to play there yet. “The idea is to look after and restore our barranca here where we live” says César, “and in doing so to set an example for other people in other neighborhoods to do the same, to show them what is possible.”

The people who are beginning to look after the barrancas now are trying to restore places they care about. Some of them also think in terms of restoring ecosystem services that they value, including those of clean water supply, temperature regulation, and flood mitigation, as well as recreational opportunities. Some see cleaning up as a political act, even a transgressive act. If mess is normal, clean provokes rethinking, as do citizen led initiatives versus reliance on government, says Javier, who works tirelessly during the cleanup. He doesn’t wait for organized events to do this and he later showed me viewpoints and entrances to the barranca, which he regularly sweeps up to make them look more attractive. He extracts the dead leaves and other organic matter to make a substrate for the street planters that he constructs from recycled crates and installs all along his street, which he also cleans up. “I’m doing an environmental education campaign,” he says, “but not with my mouth.”

Javier says that many people have asked him why he’s cleaning the street. “Who’s coming?” they ask, some are sarcastic and many say that it’s the government’s job. I tell him about my similar experiences cleaning up Manchester canals, where people asked me more than once if I was doing community service as punishment for some crime I had committed. But Javier’s neighbors have for the most part stopped littering and some have started watering the plants; some have asked him if they can have a planter in front of their house. He would now like to acquire a key to the gate of the Salto Chico so he can regularly take groups of young people in to clean and restore it. Javier notes that a lot of people talk about problems in terms of what’s wrong with government, but he says, “I don’t like to talk about good or bad governments; I prefer to speak about good or passive people, because the destruction of beauty was done by all of us, and now we’re waiting for someone to fix it. We need to do it and we can begin to make a difference in days.”

Despite César’s insistence that no one should put their stamp on the big cleanup or the overall effort to restore the barranca, local politicians are soon descending the path, ready to pose for photographs. “That’s ok,” says César, “they bring people. [The people from different agencies] bring people. We need them all… We have short, medium, and long-term goals. Citizens can keep working and if it’s not this government that gets behind it, then maybe it will be the next one. The stages are first cleaning up, then water treatment, and then reforestation of the barrancas.” César believes that the barrancas need the protection of being classified as parks in order to limit what is built on them and what is thrown into them. He wants them to move from places that belong to no one to places that belong to everyone.

Janice Astbury

London

References

Alvarado Rosas, C. & Di Castro Stringher, M.R. (2013). Cuernavaca, ciudad fragmentada: Sus barrancas y urbanizaciones cerradas. Universidad Autonoma del Estado del Morelos and Juan Pablos Editor, S.A.

Jorgensen, A. (2011). Introduction to Urban Wildscapes. In A. Jorgensen & R. Keenan (Eds.), Urban Wildscapes (pp. 1–14). Taylor & Francis USA.

Ruff, A. (2000). The biography of Philips Park Manchester 1846-1996. School of Planning and Landscape, University of Manchester.

Janice nos conocimos en la UAEM. ¿Cuándo vuelves a Cuernavaca? Queremos mostrarte un proyecto comunitario para la zona norte de la barranca Amanalco. Saludos.

In Mexico City, the environmental law has a barranca category to defend and to have an environmental management plan and to protect this places. It is not the most effectve, but it is something. Maybe could work to promote this in with the Cuernavaca lawmakers.

Congratulations for the effort!

Congratulations for your article…When are you coming back to Cuernavaca?…Let me know, to organize a coffee meeting with Cesar and some of the other guys…

Un abrazo… Manuel