For city planners and those interested in addressing sustainability of the city as its interrelates with nature, we are very familiar with the pervasive discourse of climate change and the idea of adaptation to, as well as mitigation of, climate change effects and causes.

Even with a degree of mitigation, adaptation that enables the short-term continuation of existing infrastructure and accruing tensions, rather than being part of a process of necessary reorganizing, becomes part of the “sustainability” of an increasingly frail status quo. In other words, certain kinds of adaptation can enable the current system to continue on a similar trajectory. An important critical consideration in sustainability is: what is being sustained, for whom, and who (or what) is being left out?

Living for the city: the greening of late modernity

Cities are human’s largest constructed artifacts and the locus of the majority of the world’s population. In places such as the U.S., our existing cities saw their greatest growth based on the infrastructure and underlying logic of “high modernity”—a logic of production that reigned supreme from 1930-1970. This includes the grey infrastructure-based logic of seeking concrete control of nature, which has resulted in the fragmentation and destruction of our relations to accessing the natural processes of place. This logic also includes the capitalist imperatives of growth centered on property markets, goods movement, profit reinvestment, and commerce backed by the rationalized sciences of economics, efficiency and professional planning. This overall structural complex of high modernity has created the foundation for the sprawl, consumption, technological-fixes, and industrial landscapes we take for granted. The resulting trajectory of this logic, should it continue to be applied, is what we describe in our climate plans as “business as usual.” This is a path that routinely supports “making a killing” as a way of making a living, but, as we know, does not support the living part of our lives in a deep sense, nor the living parts for our landscape ecologies. The sustainability industry is our response to this path—part of a larger “postmodern” environmental effort to ostensibly challenge and re-orient pervading capitalist logic and its built environmental manifestations.

In such a context, sustainability appears to be part of a clear, progressive movement. Yet, capitalist production has the capacity to morph and co-opt sustainability or greening through its logic of disinvestment, reinvestment, and consumption. How genuinely reformative, or transformative, is the emerging practice of applied interventions that we call sustainability? How would we even judge this quality?

Contemplating these questions is a rabbit hole that professional planners are typically trained and advised to avoid. We are not afforded the luxury to think through such critical (read: philosophical) conundrums. There are pragmatic and political concerns to consider; after all, we do not have a blank slate. Rather, we do what we can and hope for the best. In sustainability planning, there is an implicit idea that, somehow, we can balance planet, people, and profit in a form of green, more humane capitalism. The unfortunate elephant in the room is, we know by our own equations and science that as it stands, despite noble political efforts, what we are doing will certainly not be enough to prevent devastating consequences of climate change. We wait, hopefully, for the increasingly realized crisis to prompt deeper critical action, but this is like the homeowner calling for the architectural engineer to save them in the midst of an earthquake.

At this point, we need proactive strategic planning that doesn’t just adapt, as if in acquiescence, for anticipated future scenarios, but that immediately serves a functional purpose by morphing the existing built environment to produce a qualitative difference. The best analogy I like to use is the notion of “retrofitting”: much as the architect seeks to transform the performance of an existing unsustainable building by retrofitting within the given structure instead of razing it completely, we must seek to adapt strategically, so that the performance and capacity of the structure can become fundamentally different. While other unsustainable parts may, in time, fall away, a new emergent infrastructure is set in place. This is what I refer to as transformative adaptation.

My analogy to architectural retrofitting only goes so far, however. While we have a good understanding of structural engineering forces that affect buildings, the place structure of a multilayered, multivariable city is exceedingly complex. We have to create this path as we walk along it. Fortunately, we do have a reference point to orient us—the living nature within cities, often obscured in our everyday routines, plays a vital role in increasing our livability, but is also part of dynamic natural processes which we must carefully understand and work to integrate.

The nature-and-culture fabric of urban greening

What relates nature in the city and its associated living qualities to transformative adaptation? Part of transformative adaptation is about a built environment place that supports layers of interconnected and diverse life—from the nature of place to the culture of place (and its people—such that this nature is woven into the fabric of the city across and between scales. Clearly, this is the not the current case in our cities.

Nature manifests itself to people in cities through glimpses of the seasons and days unfolding, but not as obviously as outside cities, where the intimate ground, the water, the sky, the air, and the nested ecologies that prevail awaken our senses to this whole. There are, of course, places that do alert us to these connections very clearly, but they are the exceptional refuges, the greenbelts, the nature parks, that are not found everywhere nor are made easily accessible to all. Nevertheless, connections to nature are frequently located in less recognized forms: the marginal places of dumping and disuse, such as a trash-filled storm drain opening to a vine-infested, fenced-off creek culvert.

Likewise, a city’s culture is widely and loudly celebrated—but only as a chamber-of-commerce-packaged version or as (re)discovered exotica, soon to be commodified. Today, the ground where culture should be living and emerging organically more closely resembles the sad toil of the factory farm, where cultivation happens at the margins and in the cuts, especially for those of the dispossessed creative class. There is little, if any, ability for people below the formal municipal scale—for example, at the neighborhood level scale—to openly shape their lived places and express shared social aspirations as part of the city’s mosaic.

A rich urban ecology means living nature should support other, diverse living natures, and that living culture should support other layers of diverse cultures. Both are important for our psychological and physical health. For our livability, focusing on the human scale is also key. In fact, specific locations of culture and locations of nature are two significant assets of a city and, as far as structure, these should be valued, protected, enhanced, and interconnected—cross-woven as ends of a transitional continuum.

After waxing poetic about nature and culture, and even acknowledging their anemic presence in our everyday, sterile, standardized cityscapes, we return to the topic at hand: how are these conditions related to adaptation and the role of urban green infrastructure? Environmental and climate planners recognize the significance of trees, wetlands, flood plains, and rechargeable water regimes to environmental adaptation of urban heat island, sea-level rise, storm surges, and other climate effects. How do these types of greening interventions relate to how we, the city dwellers, in our everyday rituals, relate to the place, move about, interact, and collectively contribute to the production of the cultural city landscape?

I assert that the ability to know, see, and interact directly with natural processes in our everyday city life; the ability to know and create cultural expression in the everyday, provides, over time, a calibrated “organic” understanding of place and an experiential understanding of what is at stake in sustainability, what is important to sustain, and possible new ways to communicate this importance. The presence of these direction interactions with nature is missing in so many “disempowered” communities but could support organic empowerment and a sense of relational “ownership” in place that can mitigate the pushes of displacement.

By bringing together place-based nature and culture, we are now reaching the point at which adaptation has a potential to become transformative: as we adapt to climate changes, we are also, in that very intervention, taking greening actions that seek to reawaken spaces that can orient all of us to a living logic—one that is not beholden to academic mastery, but which becomes part of our everyday formative landscape as it integrates with the functional fabric and structure of our cities.

The planning practice of urban greening

As a counterpoint, let us now examine how well intended adaptation and urban greening happens in a city planning context ruled by layers of grey infrastructural forms (and the logic that supports them). Urban greening is one of the latest catchall terms that is a complement to sustainable climate action-oriented planning, crossing-over with co-interests in resiliency, health, and equity. For some, urban greening may include green tech installations, such as solar arrays, smart energy grids, or green roofs. For others, it may connote the conviviality of linear parks and green boulevards from the “City Beautiful/Garden City” movements of the 1990s. Typically though, it refers to green infrastructure elements such as bioswales and vegetative air pollution or storm-surge/sea-level rise buffers.

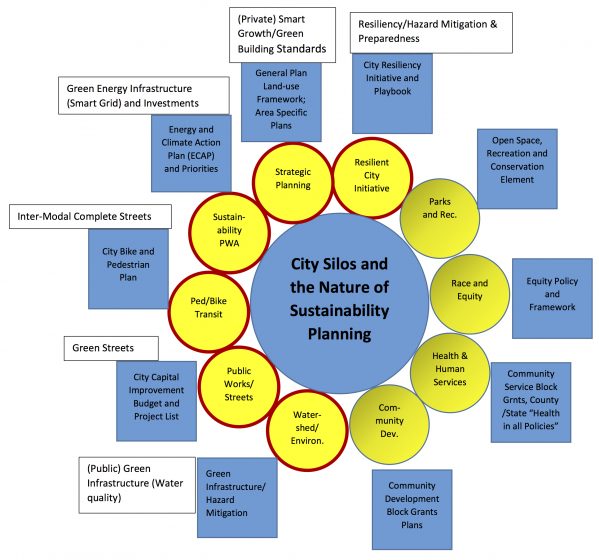

Unfortunately, the medley of urban greening connotations also mixes with a medley of responsible municipal implementers, styles of implementation, and sustainability goals which, taken together, have created a confusing and often ad-hoc landscape with little overarching coordination or, as I argue, transformative capacity. For example, in my own city of Oakland, California, where I have worked as a planner and a practitioner, the panoply of greening actions are typically operations proceeding in their own silos across more than eight different professional departments: land-use planners focus on incentivizing private-side concentrated smart growth development to mitigate sprawl and incorporate green building or site aspects as a permit condition; the sustainability units (housed in Public Works) manage the carbon-reduction prioritized energy and climate action planning process; the Public Works environmental department oversees city trees and waterways while the Transportation Departments focuses on engineering streets, sidewalks, and bicycle facilities; the Parks Department has urban nature in its purview but is preoccupied with recreation services. Meanwhile, entire other departments and offices deal respectively with culture/arts, resiliency, and equity concerns. Outside of the City, County and regional agencies are responsible for environmental and public health, air pollution, safety and hazard preparedness, and adaptation to sea level rise. Bringing these together is a monumental bureaucratic effort.

In the context of adaptation, sustainability managers may have the broadest climate planning mandate, but only have recommendatory and marginal influence. Land-use planners have formal tools of visioning, and they manage the legally adopted City master plan, but they prioritize the private sector, not public infrastructure or facilities. Public Works has the most implementing authority and funding availability, but as the organization consists predominantly of engineers, it has become pragmatically focused with available standards, value-engineering, and solving immediate problems.

The existing ad hoc conditions unfortunately mean that what little planning does happen is not connected to coordinated or critical-level implementation. Further, while they are exciting, press-worthy, and may even nudge the bar for sustainability higher, a creek restoration, several blocks of protected bike lanes, new recycled water projects, even solar-powered electric car charging stations are actions that remain “boutique pilot projects” in certain areas, which have yet to be integrated or to rise to a critical level of transformation. Other big investments in LEED-certified transit villages and bus rapid transit lines become magnets for new development and thus embroiled in issues of gentrification and affordability that only nominally involve local residents.

Certainly, these are sincere progressive efforts, but the land-use and transportation system still overwhelmingly reverberate with the existing logic of growth. Such initiatives pump millions into improving the function of grey infrastructure, sometimes in the guise of green marketing. In the end, even a functionally resilient city, if it occludes urban nature or caters to the well-off but threatens the culture and livelihoods of working class and other families, is not truly sustainable.

Still, if we seek to be critically strategic in adaptation, we need to: plan how these urban greening approaches integrate (with all departments and areas of adaptation); articulate how they can specifically incorporate mitigation as part of their function; indicate how they directly involve the nature and culture of place; and figure out how they can be comprehensively and equitably applied. Most importantly, as a civic initiative, the best place to start with transformative adaptation is on publically-held lands and facilities.

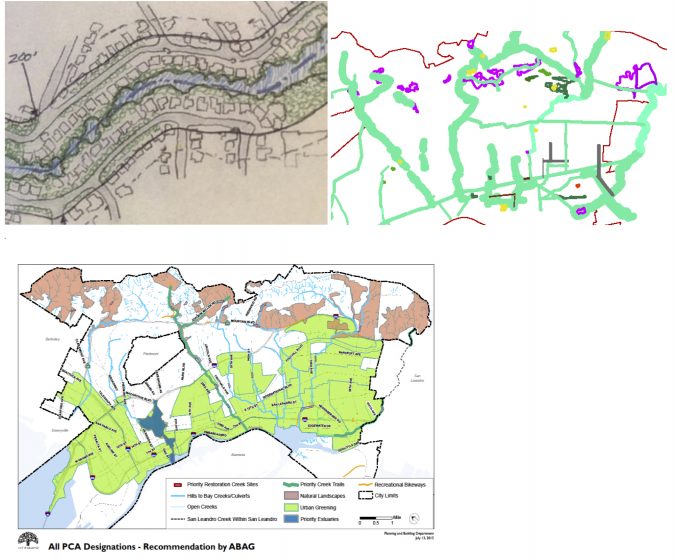

The energy and capacity for creativity, “ground-truthing,” cultural expression, and championing projects comes from the grassroots, community-based organizations that can support, guide, and hold city planners accountable while also helping to garner outside funding resources. Oakland has clearly demonstrated this energy—a coalition of community-based organizations (Oakland Climate Action Coalition, Rooted In Resilience, Communities for a Better Environment, Asian Pacific Environmental Network, Unity Council, Oakland Food Policy Council, Urban ReLeaf, Health for Oakland’s People and Environment, West Oakland Environmental Indicators, and East Oakland Building Healthy Communities, among others) along with the leadership of the Merritt community college Environmental Studies Program pushed the City in 2015 to develop a comprehensive urban greening plan that begins to meet the above criteria. What is salient about this grassroots plan is that it features a network of interconnected, watershed-based “greenways” along eight of the city’s creeks that connect neighborhoods, weaving their fabrics together and defining the unique features of the city’s topos. Another critical feature is that the plan calls for local involvement in planning, design, building, stewardship, and ancillary usage.

As a key element of living urban nature, water infrastructure—which is often part of publicly-controlled rights of way or easements—is an ideal place to start adaptation that involves ecological restoration, flood plain management, and resource conservation as well as linear open space, access, gathering spots, gardens, and paths for adjacent residents. These can be interlaced with other urban greening corridors along abandoned rail lines or green streets. Not surprisingly, this green network pattern is concurrently emerging in many places. Cities such as Hamburg in Germany are leading examples of bold, comprehensive planning, and cities large to small across the U.S., such as Detroit, Minneapolis, and Madison, Wisconsin are actively planning and building greenway networks as part of alternate infrastructural forms. Oakland’s newest San Leandro Creek greenway moves towards innovative, design-build implementation as an environmental justice victory; project advocates hopes the San Leandro Creek greenway’s success can also propel the city to the forefront of integrative urban greening planning that encapsulates sustainability, resiliency, health, and equity—and, as such, becomes a living foundation for transformative adaptation.

David Ralston

Oakland

References and links

Angelo, Hilary. (2017): “Nature in the City” in Places: https://placesjournal.org/reading-list/nature-in-the-city/

Beatley, Timothy (2010) Biophillic Cities; www.biophiliccities.org

Das PK (2015). Let Streams of Linear Open Spaces Flow Across Urban Landscapes. The Nature of Cities (August 12, 2015).

Faggi A, Vidal CZ (2016). Linear Parks: Meeting People’s Everyday Needs for Secure Recreation, Commuting, and Access to Nature. The Nature of Cities (April 14, 2016).

Maddox D (2016). Justice and Geometry in the Form of Linear Parks. The Nature of Cities (April 18, 2016).

Oakland Climate Action Coalition: Oakland City Council Greenlights “Equity Checklist;” Adopts OCAC’s PCA Recommendations: http://oaklandclimateaction.org/news/

Ralston, David C. (2016): “Climate Action Planning and Urban Greenways: Weaving Together Sustainability, Health and Resilience” in Greenways and Landscapes of Change – Proceedings of the 5th Fabos Greenways Conference, Budapest: https://sites.google.com/site/fabos2016/publication

Scott, Allen J. and Michael Storper: The Nature of Cities: The Scope and Limits of Urban Theory, in the International journal of urban and regional research (Volume 39, Issue 1, January 2015): http://www.ijurr.org/

Other relevant links

City of Hamburg Green Network Plan – http://www.archdaily.com/464394/hamburg-s-plan-to-eliminate-cars-in-20-years

San Leandro Creek Urban Greenway Project, Merritt College: www.ecomerrit.com

Urban Theory Lab, Harvard Graduate School of Design: http://urbantheorylab.net/publications/

Nordhaus, Ted and Michael Shellenberger, 2005: “The Death of Environmentalism: Global Warming Politics in a Post-Environmental World” in Grist: http://grist.org/article/doe-reprint/

Add a Comment

Join our conversation