The historic gardens of Western civilization typically include segments that were municipal areas, hunting grounds, or, on occasion, fragments of the region’s original forest. Many of the Italian, French, and English gardens that establish the history of landscape gardening were interventions added within or onto lands that, originally, were uncultivated royal reserves. While the architectural garden is typically what history records as advancing principles and concepts of landscape, architecture, and urban design, what is often overlooked is the importance of the uncultivated landscape that remained around the garden—or, in some instances, sections of it that were assimilated into Renaissance designs.

The idea advanced by re-wilding is the memory of a landscape type—a woodland, wetland, prairie—made manifest.

For example, what is typically known as the Villa Lante in Italy is a Renaissance garden set within a much larger natural preserve that was also owned by the founding Gambara family. Before political activities moved out of Paris to Versailles and it became a garden, the site served as a hunting lodge surrounded by an uncultivated forest. Likewise, King Henry the XIII originally acquired the area known today as Regent’s Park in London for hunting and leisure before historical circumstances began a process of transforming it from private lands into the public park that it is today.

The uncultivated areas of these gardens served as settings for hunting, horseback riding, and strolling with allies and adversaries—and as an intellectual counterpoint to the metaphors, abstractions, and narratives to the architectural gardens they supported. While the uncultivated segments may be less interesting to history and design students when compared with the architecturally elaborate gardens they complemented, the appearance of megacities and the intersection of their challenges with environmental issues provide reasons to reconsider a new purpose and potential for uncultivated landscapes.

“Re-wilding” is an emerging discourse within contemporary landscape design—an intriguing topic with possibilities and interesting issues. Where historic gardens made the natural reserves secondary and placed them in service to architectural gardens and their cultivated experiments, re-wilding offers the potential to make “wildness” the priority, putting the cultivated landscapes in service to UN-cultivation. What follows in this article is an overview of select terms, case studies, and examples related to the emerging topic of re-wilding.

Re-wilding: terms, definitions, and clarifications

Re-wilding describes a landscape design and construction approach that reestablishes and/or restores an area of land to an uncultivated state. It may also involve the reintroduction of species that have been driven out or exterminated by previous events; g enerally, however, re-wilding accepts that it is impractical, if not impossible to reestablish a textbook example of an “original” landscape and its ecology. Modifications to the reconstituted landscapes produce synthetic alternatives that avoid the trap and problem of ecologically achieving the original landscape.

All architecture—and landscape architecture, by extension—is fiction. Whether the fiction involves a narrative, metaphors, or abstractions, what separates shelter from architecture and landscapes from non-landscapes are ideas, shaped and constructed. The fiction advanced by re-wilding is the memory of an intended landscape type—a woodland, wetland, prairie—that is heightened by suppressing the appearance and evidence of human hands. Adding or including wildlife into the production, where possible and appropriate, further amplifies the design program and intention for re-wilding.

In any design work, appropriateness is an important parameter. Where contemporary landscape architecture enjoys the poetic potential that suggests metaphors of a wild landscape—such as wading grasses and native plants in an urban park—art is not the objective for re-wilding.

Re-wilding is a memory trope that drives establishment of a wild landscape, as close as the physical, urban, and ecological parameters will allow. In the same sense that an uncultivated environment performs multiple services, such as groundwater recharge, water quality improvements, and environmental cooling, the re-wilded landscape should offer the same potential. The addition and/or attraction of wildlife not only increases the ecological services that a re-wilded landscape can perform, it heightens and intensifies the intellectual presentation of the memory project.

Re-wilding also accepts that any such work is as constructed, engineered, and human-made as any other landscape trope that is concerned with the conventions of abstraction, transformation, ambiguity, and poetics. An encapsulation of the intellectual intent may best be explained through Simon Schama’s seminal work, Landscape and Memory.

Landscape & Memory—critical to understanding re-wilding

In his seminal book, Landscape & Memory, historian, documentary filmmaker, and writer Simon Schama introduced a compelling insight into the meaning and perceptions of landscape. “Before it can ever be repose for the senses, landscape is the work of the mind,” Schama wrote. “Its scenery is built up as much from strata of memory as from layers of rock.”

Landscape is a uniquely human phenomenon and activity. Its reality does not center on flora and/or fauna, but rather, in the associations that humans have tenaciously imprinted on nature and internalized in meanings, relationships, and emotions that are recalled through experience.

As a cultivated example, the fine lawn of an American front yard is the “memory” of an English garden and noble estate. In the example of an uncultivated landscape, the American Great Plains is a “landscape of venture” because American history and westward expansion imprinted and mythologized legends and events. To paraphrase Simon Schama: “The prairie has no awareness it represents progress and the future to American lore. But we do.”

A key to understanding re-wilding accurately is making clear that the objective is as much about memory as it is about reconstituting natural plant systems and animal species. Tapping into the memory and recall associated with a particular landscape type through a synthesis and adaptation of a “wild” landscape is the goal and intellectual intention.

The Sprint World Headquarters Campus: a case study for memory and re-wilding.

A significant 68-acre portion of the landscape architecture for the 212-acre Sprint World Headquarters Campus in suburban Kansas City was a first step towards what can be retroactively viewed as a re-wilded Konza prairie and wetland.

Surrounding a corporate campus of 21 mixed-use office buildings that are linked by seven elaborately designed garden quadrangles is a reconstituted landscape of Konza Prairie grasses and a 17-acre wetland that is located at the low-point of the campus topography. Because the interaction of 14,000 employees was to be concentrated within the habitable quadrangles, the seven landscapes are variations on garden metaphors. By contrast, the perimeter of the campus is a non-irrigated belt of prairie grasses and native plant materials that, after installation, have attracted coyotes, foxes, and several species of birds and waterfowl in the wetland and its preserved stand of timber.

Given that the corporate campus is situated within suburban Overland Park, Kansas —a southern suburban of Kansas City, Kansas—burning the installation twice a year to rejuvenate an academically authentic ecology wasn’t realistic or feasible. Memory and the “sense of prairie” became the actual goal and a workaround to the practical problems, which were solved by planting a modified mix of grass species that were adapted to mowing and to the invasive species that were present in the suburban context.

Applications for re-wilding and their benefits

Urban planning experts extol density, saying that “density offers hope”. However, suburban megacities are typically settled at exceptionally spare densities that make them virtually impossible to densify by conventional means. For example, the metropolitan area of Dallas-Fort Worth in the United States is settled at an average human density of one person per acre, as are other American cities, including Atlanta, Albuquerque, and Houston. Phoenix contains less than one person per acre. New York, Paris, and Hong Kong have densities well above 100 persons per acre. In some cases, during the workday, these cities reach densities of 500 to 1,000 persons per acre.

While the New Urbanism and urban planning examples of European cities provide potential planning methods that can apply to nodes, concentrations, and areas of greater agglomeration, they generally do not apply to the thin and diffuse geography of a suburban megacity. As a result, wildlife is beginning to emerge within suburban megacities, not merely as varmints and rodents, but rather as members of vertical food chains that include predators such as coyotes, red fox, bobcats, javelinas, and bald eagles.

Graduate programs in wildlife are establishing in suburban megacities such as Dallas-Fort Worth to study this new and expanding phenomenon. Taken together, the documentary evidence and the unassailable persistence of the emerging wildlife afford a new and originally unforeseen possibility to retroactively rationalize the low density geography of a suburban megacity as a new kind of phenomenon where civilization and wild life coexist.

In the formative history of the American suburb, the sparse density of suburban sprawl was conceived as a development pattern that could be rapidly proliferated. As a landscape character and image, the mowed lawns and clipped hedges of American suburbia merged dwelling with the nature of an Arcadian, English-like landscape. However, Arcadia requires cultivation: mowing, watering, and extensive resources for upkeep, which strain personal households and homeowners associations to sustain. Front yards, rights of way, and parks that were once seen as the fine lawns of a noble estate could begin to transform into a new and more practical landscape blending civilization and wildlife.

This is a profound and new way of reconceiving and restructuring suburban cities that also overturns the old urban paradigm juxtaposing cities with wilderness. The premodern paradigm is a two-dimensional construct that locates civilization, law, and culture inside a physical and psychological world that is protected from an uncivilized wilderness surrounding the city, outside. However, vague and blurred geographies of suburban megacities have allowed wild species the opportunity to take hold and even establish food chains. Whereas wilderness and nature were once a matter of “outside”, wild species are now rising as a new ecological layer within the city.

Using Google to search “Bobcat City” will link to a video produced by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Foundation that documents the study of urban wildcats (that is, bobcats) in the low-density geography of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. Related to this example and activity, The Dallas-Fort Worth Urban Wildlife Club and Face book page tracks and documents a daily record of other wildlife and species when they are spotted.

The shift from cultivated English landscapes, to the contemporary impulse for native plants and then, ultimately, carefully planned wild reserves within an incorporated city geography—a geography where birds, pollinators, predators, and others coexist with human civilization—affords an intriguing new way to live. That this possibility is materializing retroactively in suburban megacities, rather than as an intention that was part of the original suburban project, also holds the promise of shaping a sustainable future where children and generations grow up in a metaphorical “wild classroom,”cultivating an awareness and an immediate relationship with nature that could be a reminder about the human condition and its relationship to Earth.

The Dallas Trinity River project: a case study, re-wilded

Over the course of some 40 years, eight celebrated landscape architects and their firms have proposed design concepts to transform a half-mile wide, engineered floodway through downtown Dallas-Fort Worth into an urban park. Known as the Trinity River Project, the 7.5-mile long, 2,000 acre, treeless landscape formed by earthen levees of erosion-control grasses and pothole wetlands, teases the imagination with potential.

However, the floodway is also a hydrological bottleneck that concentrates stormwater runoff that is collected in several million urban acres upstream in Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. The practical demands generated by the floodway present a stupefying set of problems that no single design has yet to comprehensively solve.

When the expansive floodway is brimming from levee to levee with stormwater, the hydrostatic head and the flow velocity through the area has been measured at nine feet per second—a speed calculated by engineers as the frictional equivalent of a 177-mile per hour wind or Category Five hurricane scouring across the flat and treeless landscape surface. Other collateral effects compound the impact of the current and flooding.

Expansive silt bars are deposited with each flood event. The June 2015 flood, which resulted from monsoon-like rains that lasted for over one continuous month, deposited silt bars approximately 20 inches deep over jogging trails and walkways, as well as Trammell Crow Park, a small pond and respite built in the late 1980s. In addition to the silt bars, enormous trash snags tend to accumulate around and between the piers of several vehicular bridges that cross the floodway. The agglomerations of plastic bottles, driftwood, suburban toys, and other sharp objects brought into the floodway can grow to several acres in size. The debris presents a formidable problem for maintenance, upkeep, and the related costs to accomplish it. Recently, silt bars created by the June 2015 flood rendered the area’s trail system and its attendant parking lots unusable for over a year.

Beyond to observable debris, environmental experts point out that the incoming stormwater flow is rich in concentrated urban toxins that become incorporated within the silt layers. As an expert cleverly explained at a symposium on the Trinity River, the floodway is a clever “self-healing landfill” that safely encapsulates the toxins within countless layers of silt that naturally form after each rain event.

Setting the hefty demands of this landscape aside, what observers see today is a landscape that resembles a grassy marsh with wading birds, waterfowl, coyotes, red fox, and other wildlife drawn to the area by its ecology and the food sources it presently offers.

A concept known as the “Balanced Vision Plan” has been prepared for the landscape by WRT, a renowned Philadelphia-based landscape and planning firm; it has achieved federal approval by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Founded by the legendary landscape architect Ian McHarg, over seven or so years of work, public meetings, and design, WRT developed a solution for Trinity Marsh that included naturalizing meadows; wetlands; active recreation fields organized by a chain of lakes and marshes; and a network of trails, paths, and accessible parking that ties it all together.

Thus far, WRT and their team of consultants and engineers have advanced the technical documentation and specifications for this project to a 35 percent point of completion. Sixty-five percent of the process remains to complete before the project can be publicly bid for construction.

As the project awaits authorization to proceed, a group of former City Council members, conscientious activists, and civic enthusiasts have come forward to laud the virtues of the Balanced Vision Plan and also to use the documentation work that remains to be done as an opportunity to heighten the naturalizing systems the BVP includes into a re-wilding project.

Recently, a second plan for Trinity Marsh has emerged through the support and backing of Dallas patrons. It is championed by Mayor Mike Rawlings and designed by the world-renowned New York firm Michael van Valkenburgh and Associates, or MVA. The MVVA plan concentrates on a 250-acre area in the immediate vicinity of two iconic bridges that were designed by another famous engineer and architect, Santiago Calatrava.

The MVVA scheme features a sophisticated work of landscape architecture that is purpose-designed and hardened to handle the formidable flooding demands of the Trinity. The proposal extends several other waterfront projects and accomplishments by MVVA in New York and the U.S. MVVA also designed the landscape architecture around the George W. Bush Presidential Center at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, designed by Robert A.M. Stern.

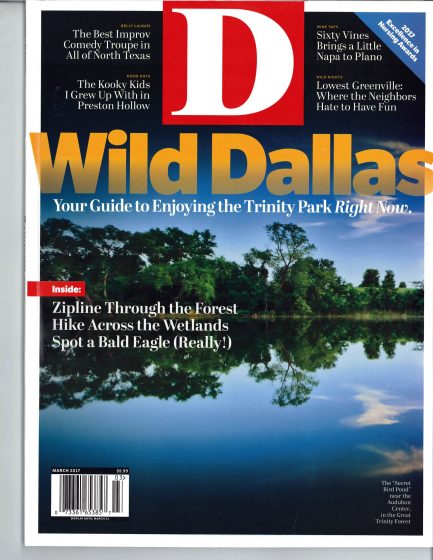

Recently, D Magazine, a regional journal published monthly that covers cultural topics and is widely read by an educated business and corporate population, devoted an entire issue , “Wild Dallas”, to the topic of re-wilding the Balanced Vision Plan. The March 2017 journal included several articles by contributors to the design, renderings, and paintings of what the area would look like as a Nature Project. In coordination with the issue, D Magazine also sponsored a conference in uptown Dallas.

Conference experts included Dr. Robert Moon, renowned master gardener and caretaker of the venerated Nasher Sculpture Center Garden; Tanya Homayoun of the Trinity River Audubon Center; Becky Board, member of the Dallas Parks and Recreation Board; and myself. Former City Councilwoman, Angela Hunt, spearheaded the conference and the effort to implement the WRT Balanced Vision Plan as a re-wilded nature reserve that will be within walking distance of downtown Dallas.

Re-wilding as redefinition

As contemporary landscape architecture converges on ecological and environmental interests, re-wilding offers a new kind of expressive potential for design by redefining how the landscape will perform, and as what. The goal of re-wilding places equal emphasis on the accommodation of a wildlife program with the human condition that it will serve. The first step is to establish re-wilded, synthetic nature that is as close to the original as is practically possible. Then, design to put people into the re-wilded area in such a way that the two can coexist.

In this light re-wilding poses no threat to, nor is it a critique of, artful landscape experimentation. Paths, benches, and pavilions can easily fit into a re-wilded space and can designed with an artful hand. However, artful indulgence to stylize the embankments of a wetland levee, for example, would be an interference with the intended landscape character of a re-wilded wetland.

Given that any design hypothesis can be taken to an extreme, re-wilding should be viewed as a particular approach to naturalistic design that pushes beyond metaphors and abstractions to approach reality as closely possible. Metaphors, which can be powerful when skillfully employed in landscape architecture, exist only as aids—secondhand conditions for a real, factual reconstitution of an original landscape.

Re-wilding should be prudently considered and understood through the lens of two irreducible issues. One is appropriateness; the site, program, and location for where re-wilding might be considered. Secondly, re-wilding fundamentally requires considering the designing for a program of wildlife as equally important to designing the landscape as a place that can be inhabited by people.

With respect to appropriateness, for example, the prairie grass installation around the Sprint Campus in Kansas City establishes a landscape of memory that could attract wildlife—none were deliberately introduced into it. An academic reconstruction of the Konza prairie wasn’t practical, since the fire required to rejuvenate the original species, along with the invasive suburban species it would have been susceptible to, required an “adjusted” plant mix to be resilient and practical. After 15 years, thick stands of wading grasses have attracted coyotes and red fox. Several species of raptor are frequently seen plunging into the grasses for the shrews, field mice, and voles it also contains—an activity that only heightens the memory trope rising from within the campus: the original landscape.

Rather than conventional modalities, which are driven by theory, technology, or personal design style preferences, re-wilding offers an intensely performative landscape that takes the notion of naturalism to an extreme. Re-wilding is not a postmodern retrogression, receding from the future and the uncertainties it presents. Going forward, I am intrigued to observe and participate in re-wilding’s development and proliferation as an organizing concept in landscape architecture.

Kevin Sloan

Dallas-Fort Worth

Leave a Reply