In this post, we report on a recent design workshop at National Cheng Kung University, or NCKU, in Tainan, Taiwan, a continuation a series of of intensive practicums held at undergraduate schools of architecture in successive locations internationally since 2008. The work presented here extends from our last essay, posted four years ago in May, 2013, titled Measuring the Sensori-Motor City.

The machinic scene-image as a design tool strengthens and magnifies certain essences of dynamic urban change.

These workshops have offered new tools for an integrated architectural, ecological and social analysis of the contemporary city to TNOC readers. The NCKU workshop most recently was co-sponsored by the Kaohsiung, Taiwan Municipal Government Urban Development Bureau to explore ways to introduce new thinking around the urban transition of the historical Hamasen port area. The workshop used a conceptual framework titled “eight machinic scenes” in order to frame the workshop conceptually and to structure the thinking around the design of temporary installations and exhibitions to generate discussion between Hamasen citizens and visitors with the urban development bureau in reimagining the future of the old port neighborhood.

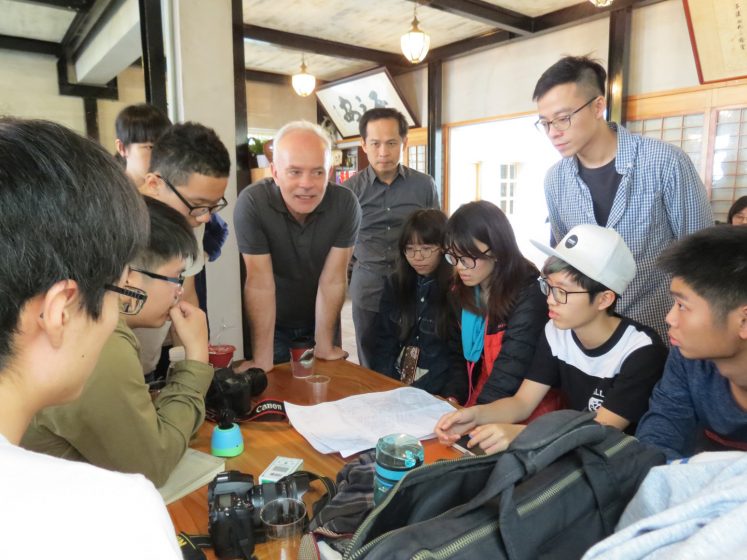

The workshop was structured by three two-day, intensive sessions. First, the machinic nature of the city was diagramed through three abstractions of ecological, industrial, and social flows. The machine metaphor was employed in order to trigger an immediate discussion about urban systems and processes rather than architectural objects and urban form. The second phase situated these three thematic diagrams within aesthetic scenes cinematically framed by three camera points of view: still, mechanically moving, or freely moving. The machinic analysis and cinematic scenes were synthesized in the final phase, which resulted in a 1:1 scale installation device back in the NCKU campus.

The experimental workshop was not just a tool for architectural design or urban development, but was also a performative machine and a dramatic scene in itself. With 40 students, 10 faculty, and the municipal urban development bureau, there were multiple moving parts, inputs of information and energy, and a considerable amount of creative output. We created quite a scene ourselves during our invasion of the historical city on a beautiful spring weekend in March. The machinic power of collaborative academic pursuits digested and processed an enormous amount of information in a short, intensive period. The situated installations incubated during the workshop are seen as rehearsals for opportunities to install variations of the eight scenic devices developed here in various public venues back in Hamasen.

Three urban machines

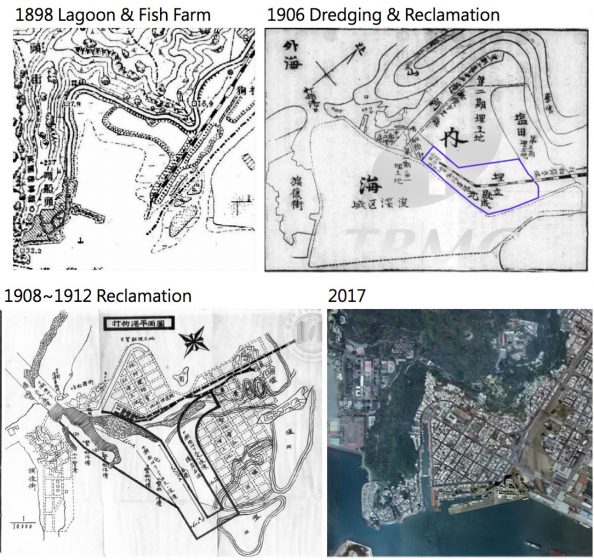

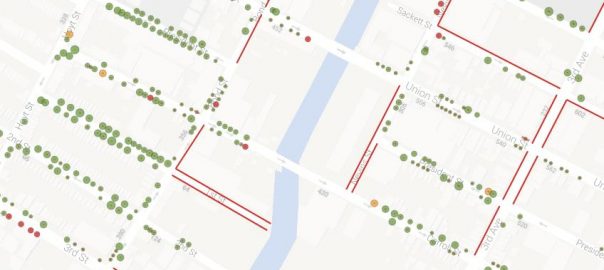

Nature is scientifically measured as an ecological processing machine where, for instance, sun energy can be measured as heat and photosynthesis can be measured as vegetative growth. Plant volume in turn produces a respiratory machinery, organic decomposed litter, and food for herbivores, which in turn feed carnivores—all which can be quantified. Hamasen sits on the mainland shore near the mouth of a natural lagoon within an alluvial delta of Kaohsiung’s Love River. A rugged limestone mountain forms the lagoon’s mouth, the result of coral activity taking place over centuries near the end of Taiwan’s largest river by drainage area, the Gaoping, to the east. The Gaoping’s considerable sediment deposits have been carried west by ocean currents over time, creating a barrier island between the coral mountain and river delta. A lagoon is an ecological machine in itself, being a shallow body of salt and fresh water mix with less tidal fluctuation than open harbors or estuaries.

The Japanese colonization of Taiwan began the industrial machine at Hamasen. Military planners laid out the port town of Hamasen on a triangular piece of land between the coral mountain lagoon mouth and Love river delta. Hamasen means beach rail line in Japanese, and the town was bracketed by the mountain to the north and west, and rail lines to the south and east. The colonizers constructed waterside quays on the west side of the gridded settlement, as well as along the rail lines. The colonial industrial machine was built for resource extraction and sugarcane was planted inland and brought by rail to be processed into sugar at the port. The rich fishing habitat of the lagoon and open sea provided resources for a second industry, fishing. After World War II, the port of Kaohsiung became the largest in Taiwan, first with steel and petrochemical industries, and now as a logistical export zone in the age of containerization logistics.

Philosophy and psychology have referred to human history as abstract social machines and humans as desiring-machines. Taiwan is an advanced economy and a vibrant democracy with a noticeable nostalgia for the 150 years of Japanese cultural influence. Hamasen, due to its natural scenery and cultural history, has become a popular tourist site for locals, who come for the day for food, scenery, and history. The apparatus for the sightseeing industry is still developing and it includes the conversion of the rail lines into a cultural park, traditional food shops, galleries and craft, mountain trekking, and a bikeway to the west coast, as well as a popular ferry to the barrier island.

This analysis comprised the first intensive phase of the workshop, which culminated with a review and discussion of the research of the three machines which constitute Hamasen from the natural ecology, industrial history, and post-industrial future. Many of the presentations made use of timelines, charts, and diagrams to document historical changes to the lagoon, to the port area, to the city grid, and to buildings at different scales. Analysis of the relationship between the ecological, industrial, and social machines revealed an urban ecosystem in flux from the villages of Formosa to the formation of a huge metropolitan zone. The presentation looked to focus on how to locate these different aspects of urban flows and processes where they are situated within the public space of the city.

Eight urban scenes

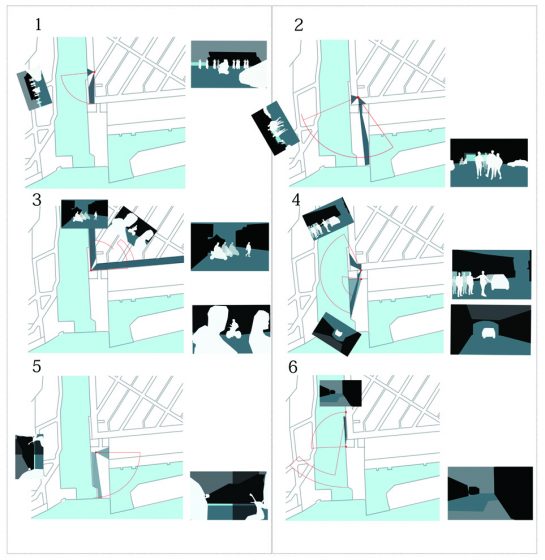

The second intensive session used “cinemetrics” video framing, shooting, and editing to measure ecological, architectural, and anthropological space, movement, and time. Cinema, the art form of the industrial age, is an ideal machinic scene-making device that has proliferated over the last decade with the increased accessibility of video cameras within handheld smart phones and the wide dissemination of these images via social media. The video camera is a tool used to frame and measure human perception, affection, action, and reflection in relation to dynamic movements in space over time. Three specific film framing styles were employed as a method to interpret the city’s still and dynamic aspects through three distinct points of view: from a still tripod; mechanically panning, tilting, or tracking; and handheld and freely moving. This exercise reflects recent research on rendering the social and the ecological in architectural scenes.

One of our framing styles was the single point, right angle, early Renaissance perspective captured in still tripod style allows students to shoot simultaneously from different 90-degree angles at different distances in order to capture scenes and events in the city. The second involved mechanically moving shots that slowly rotate left or right or tilt up and down in the grand Baroque tradition of panoramic open spaces, where actors appear and disappear in diagonal corners, but which are subject to blind spots when the shot is interrupted by physical elements. The handheld camera creates opportunities to carve through space freely. The camera interacts between the body movement of the film maker and the film subject. This open topology can extend our perception of the city and help us to explore other possibilities of space. All techniques explore and generate spaces full of multiple sensate experiences as part of a nature-culture continuum.

Our main objective was to document real flows and processes which situate the abstract machinic analysis within a cinema sequence. The filming situated the ecological, industrial, and social aspects of Hamasen and the relationship between the sightseer, residents, and workers within the context of the high levels of consumerism present there. The films excavated the nature of the routines of daily life as well as the heightened experience of weekend sightseeing. These scenes comprise various subtle relationships, so the impact of urban design at the scale of the body can be perceived through various movement systems which shape and generate the surrounding living environment. We were looking for the real experience of the urban landscape so that, as architects and urban designers, we can respond to human perception, affection, and action in more sensitive ways and create new sustainable possibilities.

Multiplying the three machine diagrams times the three styles of framing space, movement, and time results in nine possible urban scenes of Hamasen. We selected eight, as eight or ten scenes is a standard number in Chinese landscape artistic and poetic tradition. Cinema, comprised of images mechinically produced at the rate of 24 views per second, can be perceived both as multiple moving architectural views, as well as within the paradigm of traditional panoramic landscape paintings. To carry out the operation of moving-image measurement, an enormous amount of information must be quickly digested, reviewed, discussed, reshot, and edited into short, informatic sequences. Hamasen’s microclimate, ecological landscape, humanity, industry, events, and spatial changes can be explored, enhanced, or enlarged. This is a clear example and model of urban design as a combination of various senses and perceptions for urban ecosystem understanding. The city is not a fixed object, but a fluid-like interaction field that can be both machinically measured and scenically performed.

This second phase documented the static and dynamic dimensions of eight scenes in Hamasen during a brief moment in time. They were openly arranged through cinema’s montage effect, but preserved a variety of imaginary readings of memorable moments from the field. The eight scenes uncover previously unrecognized relationships in the daily life of Hamasen, which can provide a more meticulous understanding of the subtle nature of the city. The machinic scenes enable an urban design recognition of individual bodies perceiving and acting within the various movement systems that they shape and generate. The scenes imply specific moments in time, distance, height, angle, scale, speed, and point of view of and within the surrounding environment. The machinic scene-image as a design tool strengthens and magnifies certain essences and feeling of even subtle examples of dynamic urban change.

Installation devices

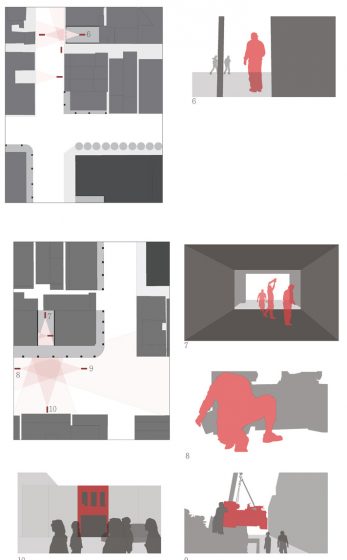

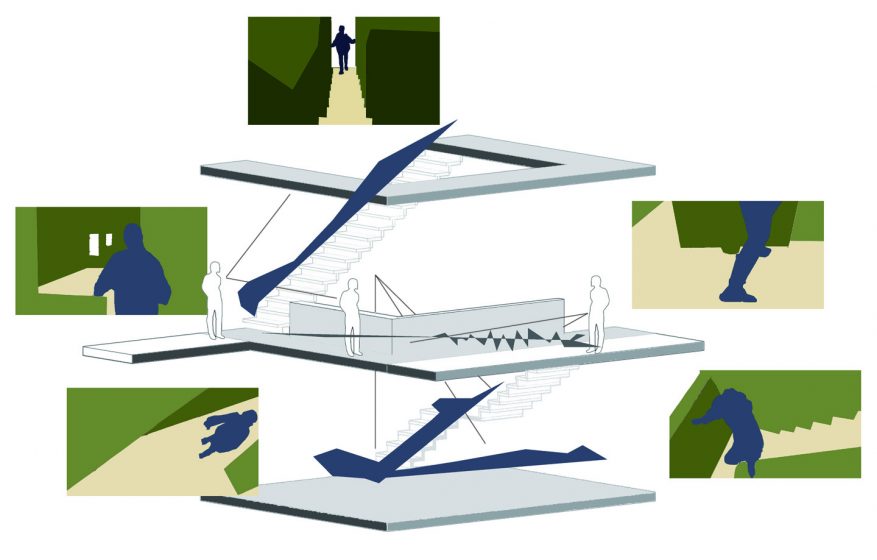

In the third intensive session of the workshop the students were asked to create physical devices to screen their videos within an interactive installation wherein the visitor would experience specific perception-movement scenic landscapes. The installation explores questions around the impact of the sightseeing industry in old Hamasen port on both its ecological and industrial pasts. Student groups developed prototypes of installation devices through which to imagine new possible futures based on a realignment of existing ecological, industrial, and social flows. The innovative proposals were designed to induce interaction between a civic audience’s bodily perception; public and private spaces; and between social disparities. When installed in the future, they are intended to create new kinds of conversational contact between residents, workers, and sightseers and Kaohsiung’s urban development and planning bureau.

The performative installation devices were located throughout the NCKU campus in eight different locations, selected to build on associations between the Hamasen site and a new “non-site”. Just three of the eight scenes, Labor Flows, Traffic Flows, and Water Flows are described below, but a larger archive of the workshop is available on a Chinese language blog.

Mirroring labor flows

The group that resulted from the combined logics of the industrial machine diagram and the intimacy of a still camera documented activities along a street of shop-houses near the old port. Their video and installation, Mirroring Labor Flows, focuses on the contrast of several shop-houses occupied by the remaining old factory laborers across from a series of new art galleries and high-end residences. In their final video below, welding, painting, and tool trading activities are juxtaposed with sightseers shooting selfies; moving trucks and fork lifts are juxtaposed with luxury cars parking; a hand exchange of money is intercut with an exchange of a camera. The montage of disparate images produces a new, conjoined imagination where social media is seen as a new kind of labor, and the decline of industry is celebrated in a modern version of the Japanese temple shrine ritual, during which obsolete machinery is ritualistically removed from its sacred interior and paraded down the street. The art tour is seen as another kind of urban ritual.

https://youtu.be/rgSwKqcqiPo

The group’s installation consisted of a device with two sets of laptop screens and mirrors. Viewers sit on one side of a table facing a screen, a mirror, and another viewer. One side of the street is projected on the screen, while the other side can be seen in the mirror, contrasting, in real time, two images that were spliced together in a montage sequence in the original video. Through this face-to-face and reflective viewing, the two separate worlds of physical and virtual labor are superimposed and face-to-face dialogue is encouraged.

The spectacle of traffic flows

The group that resulted from the combination of the social machine diagram and panoramic camera documented the busiest public space in the neighborhood—the traffic intersection in front of the ferry terminal. The flow of pedestrians, bicycles, motor scooters, and cars mix and weave gracefully in the chi of traffic. There is a graceful order and fluid geometry to the seeming chaos of disorderly vehicles and pedestrians, some knowing their way, others disoriented. This mixed movement highlights people as a self-organized flock operating by some inner logic of fluid dynamics. The camera moves to various corners of the busy plaza, with each position revealing new information or producing new blind spots. The performative installation used a rotating chair with a box-like helmet, which emphasized the movement of the human head up and down through the hollow black scene to reframe the flow as it emerges and disappears.

Gridded water flows

The group that resulted from the combination of the ecological machine diagram with the freely moving, handheld camera videoed the point of view of water flowing through the streets of Hamasen. The scene employs a method of liquid perception as the camera freely moves from the mountains to the lagoon, passing from hillside settlements through street alleys to the port. Even in the most urban of contexts, water flows according to the force of gravity acting within a topography. A set of microecosystems associated with water is made visible for high and low terrain, and the city of the machine. The performative installation featured a guided tour down from an upper level of a building through a series of iPhones installed in a descent scaling the topography of Hamasen. The hillside to the seaside section of body movement, concentrated between the staircase and the high ground, segmented the film to project a variety of different elevations capable of being perceived.

The value of machinic scenes

While the concept of seeing the city as the interaction of a number of machine-like systems comes from the industrialization’s domination of our society, a deeper, pre-industrial history of the urban landscape as a “scene” can be traced in Chinese landscape painting and poetry tradition. For example, a series of scenes described as the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” in Hangzhou was developed during the Southern Song Dynasty by Ye, Xiao Yan (circa 1000 AD). The ten scenes consist of ten drawings and poems: Dawn on the Su Causeway in Spring; Orioles Singing in the Willows; Fish Viewing at the Flower Pond; Curved Yard and Lotus Pool in Summer; Two Peaks Piercing the Clouds; Leifeng Pagoda in the Sunset; Three Ponds Tower Mirroring the Moon; Moon over the Peaceful Lake in Autumn; Evening Bell Ringing at the Nanping Hill; Remnant Snow on the Bridge in Winter. These scenes, which contain detailed ecological information within daily and seasonal cycles, continue to be depicted and visited in Hangzhou today. The classical memory of West Lake interacts with the sensation of the contemporary, sightseeing human body within a compressed timeframe. Only repeated visits offer an attentive circuit of seasonal change and ecosystem processes captured within specific heightened experiences in various seasons and at different scales, distances, and from various viewpoints.

The workshop’s ultimate association with an ancient depictions of memorable experiences served as an inspiration to reexplore the historical authenticity of Hamasan through eight machinic scenes. These scenes capture the profound urban landscape that resulted from the Japanese construction of a coastal railway line ending at the mouth of a beautiful lagoon on the southern coast of Taiwan. There grew a bustling port, market, and the origin of modern Kaohsiung. The port, once closed due to the port activities, has now reopened and has begun to transform into a complex open and public space. The eight scenes of Hamsen provide a clear example and model through which we can recognize the urban ecosystem as a combination of various senses, perceptions, memories, reflections, and possible futures.

Brian McGrath and Cheng-Luen Hsueh

New York City and Tainan

about the writer

Cheng-Luen Hsueh

Cheng-Luen Hsueh teaches in the Department of Architecture at National Cheng Kung University in Tainan, Taiwan.

Leave a Reply