What would you do if things went terribly wrong with your city after promises made by your decision-makers of an “Urban Golden Age” resulting from hosting the Olympic Games? In my city, Rio de Janeiro, my students and a lot of people I know and talk to are willing to leave not only the city, but the country. Indeed, Brazil is in a gloomy situation due to systemic corruption that has led to widespread and interrelated political, economic, social, and ecological crises.

Immersive experiences can reconnect students to urban nature—and inspire them to improve their cities.

How can a person pursue joyful living when so many find themselves in an everyday challenge to bring food to their families? In Brazil, there are more than 14.1 million unemployed people (13.7 percent of the population). Many of my colleagues and former students are jobless. Architecture and urbanism studios have dramatically shrunk, if not closed their doors because the real estate market has collapsed at all scales. Students are scared because they believe they won’t find jobs when they finish school, which is what is happening to many of their recently graduated peers.

How can you keep up the positive energy to teach future professionals that will plan and design cities when you experienced deep frustration with your own performance as an ecologically- oriented planner and designer? The “market” decides what kind of city we are living in now, and the “market” opposes all urban interventions to achieve a sustainable, resilient, and just city. The priority is not life—human or otherwise. The city is seen as a big business, the means by which to generate huge profit for a few select companies (many of which are now under legal investigation due to unimaginable levels of corruption in Brazil, with many high-level entrepreneurs, top executives, and politicians in jail).

These questions are not exclusively related to my personal experience as a Brazilian living in Rio de Janeiro. The time that Jane Jacobs foresaw in her book, Dark Age Ahead (2004), has come. We are living an urban crisis, where most urbanites are disconnected from nature, and economic volatility makes things worse. Meeting immediate needs is most people’s priority and the “market” plays with the fear to push their growth at any cost in less educated countries. Such is the case of Brazil. We now live in the Anthropocene, a new geologic epoch generated by fossil fuel-addicted society. The entity that rules the world—known as “The Market”—considers people consumers and members of the workforce, not as human beings. We are not only disconnected from nature; we are disconnected from each other. We are not a community anymore; we are individuals competing “to make a living” (this expression is quite weird for me; I believe that we need water, food, and shelter to live, and our work should fulfill us and contribute to the common good).

So now what? A bottom-up, gentle revolution

A new paradigm is emerging, and it must gain worldwide expression to overcome our great twenty-first century challenges. Cities and the local scale are at the center of this transformation in search of a more sustainable and equitable future; these movements irradiate to other areas, urban or not. The new paradigm is emerging from a bottom-up gentle revolution that is driving changes in our connection with the urban environment, where people and nature are returned to the center. Diverse people are gathering and transforming the urban landscape to have a more nature-friendly coexistence, and at the same time are cultivating civic relationships. The sense of community is being restored around themes that touch people’s hearts, such as water, rivers, organic food, trees, biodiversity, social interaction, mobility, culture, arts, and so on. The interventions that are being made by people in local communities have been called Tactical Urbanism (Garcia and Lydon 2015). Those actions are great inspirations to envision the city as a real human habitat. I have been researching bottom-up initiatives that are responsible for urban landscape changes, and have written about some of them in previous essays at TNOC.

In search of answers

As a professor at the Architecture and Urbanism Department at Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, or PUC-Rio, I decided to take students on an elective course of Ecological Landscape Design and Urban Ecology in a study trip to São Paulo. I cannot teach about landscape sitting inside a room all the time. The aim was to make the pupils feel the landscape and to enable them to meet active leaders who are articulate and are fueling a deep change in the urban landscape through the movements they have created. In this process, these leaders are mobilizing hundreds of people by reconnecting them with nature and their communities. The trip to São Paulo was a response to my own anguishes with our shady reality, and a search for answers to the questions above. My deep personal goal was to drive my students to experience real, bottom-up changes that are undergoing in this tremendously complex megalopolis.

Two PUC-Rio professors asked to join us, so the trip became even more stimulating. It became interdisciplinary: Henrique Rajão is an ecologist, and Pedro Lobão is an architect embodying a lifestyle shift driven by the jackfruit tree he has in his backyard in a residential, central neighborhood in Rio. His tree produces hundreds of fruits that he is using in a new venture as an urban food producer.

PUC-Rio is ranked as the best private university in the country. It is not affordable to everyone, in spite of offering scholarships to many students. Unfortunately, the trip was also expensive. Only students who could afford to pay extra to travel were able to join. This situation gave me an opportunity to discuss equity and justice with the economically privileged young adults who will soon be working in our cities.

We had four intense, mind-changing days together, which I will try to condense and communicate in this piece. I organized a class a few days before the excursion to prepare the students and my colleagues for the intensive program we would have later in the week.

After a very early morning flight, we went straight to the epicenter of the city: Paulista Avenue. (You can see Paulista Avenue on TV whenever public demonstrations or protests gather up to hundreds of thousands of people.) We walked along the busy avenue to meet our first hosts: architect José Bueno and geographer Luiz de Campos Jr. They are the creators of Rios e Ruas (Rivers and Streets), an initiative they started a few years ago when they met and discovered their mutual passion for the urban watercourses that have been buried underground. They became river chasers, and have brought thousands of people to realize that São Paulo has an immense treasure hidden under its streets and paved areas.

We tried to gather bellow the iconic Modernist building of the famous architect Lina Bo Bardi, the Museum of Art of São Paulo, but there was a protest against corruption that was very noisy. We crossed the avenue and went to Trianon Park, a fragment of Atlantic Forest in the heart of the Business district. It is an island of peace, so we could start our conversation. Luiz and José developed a methodology to touch everyone with sensibility and knowledge. First, they asked each student’s names and a river’s name. Yes, the name of a river as if it were the family name. It was so moving for all of us to think about a river as family, and the connection that we could have to one single watercourse. It was easy for some, and impossible for one. She didn’t have a river of which to be reminded, no memories of rivers…I found this to be so sad.

After a brief explanation about the urban rivers and the urbanization process, we headed back to the museum’s esplanade that oversees what once was the Saracura river valley. And that was our river now! After telling the history of the urban growth over the river, Luiz and José guided us in our urban expedition to discover where one of its springs still drips water; to see where a former cascade was put into pipes; and to walk in the streets where the river’s waters are flowing but hidden from our sight. Traversing these partially neglected neighborhoods, the group felt the shapes of the landscape; the water paths that follow the geomorphology and some remnant green areas; and the various periods of architectural styles and social differences in construction types. Along the way, they discovered a complex and alive city, full of diverse people. We continued until the very end of the buried river in the downtown area. There, we found a surprising illustration of nature’s resilience: a capybara was sleeping over a trash island in the channeled Tamanduateí river, were the Saracura issues its waters in a polluted brownish waterfall. It was a comprehensive class to understand geographical, ecological, social, economic, and historical interrelationships, as well as the impacts of the urban growth process.

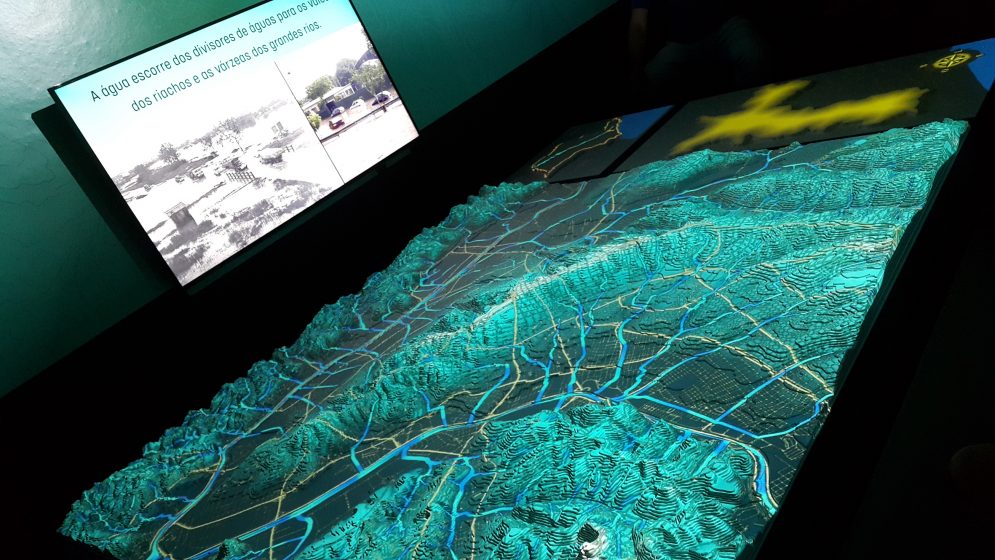

To wrap up the first day, we went to an exhibition that was conceived and organized by the two river’s lovers, Luiz and José, named Rios.Descobertos (Rivers.Discovered—the name has double meaning, referring to the discovery and uncovering of the rivers). It is a huge city model with projected images that unveil the landscape change that has occurred during the urbanization process in a dynamic, beautiful, and colorful manner. In a panel, pictures and phrases cover a wide range of geo-biophysical, social, cultural, and even emotional transformations of the city’s landscapes related to the rivers and streets. We could see and feel São Paulo as a city of waters. That was astonishing for all. All of us started to see the unseen.

The next day, our host was Nik Sabey. This young man is a former executive of an advertising company who loves trees. Ten months prior, he decided to stir up his life. He abandoned his job and stable lifestyle, and went out to plant trees all over the urban hardscape and unused lawns in public areas. He started the Novas Árvores por Aí (New Trees Over There), a collective movement that gathers hundreds of people to plant pocket forests, together with the landscape architect Ricardo Cardim—a trained dentist who studied biology to become a landscape transformer specializing in the original ecosystems of São Paulo.

Nik took us to one of the most exclusive office buildings of the city, the famous Victor Malzoni. Well known companies occupy their floors, including Google in Brazil. The monumental mirrored façade and manicured gardens hide a recently-developed, groundbreaking waste treatment facility. Organic waste (there are three restaurants on the lot) generates four tons of compost each month, which is donated to urban tree plantings. Other residues are separated and sold. At the facility, they’ve developed a subterranean demonstrative food garden, where people who work in the building can harvest fresh organic herbs (picture) and leafy greens. Bicycling is also a priority, which is very unusual in Brazil. There is a bike lane that enters the garage into the underground parking area, with showers for sweaty bikers, and even a small bike shop. Sewage is locally treated and the water is 100 percent reused. For the students who are future architects and civil engineers (we had two), this visit was a mind-blowing experience. Within ten days of her return to Rio, one student had started working in a start-up project inspired by those practices.

After being underground almost the whole morning, we ventured to one of the most discussed urban spots in recent memory: Largo da Batata (Potato Square), a former traditional and very popular site. It was totally demolished to give way to the construction of a subway line and the local station. Ten years ago, the construction collapsed and people died. When the construction was finally opened for the public, it was a concrete desert. The residents started a movement to transform it, and they called it A Batata Precisa de Você (The Potato Needs You); from then on, the site changed a lot. They planted trees and developed areas for social interactions, including designed urban furniture and playgrounds. They also gave priority to people over cars by painting pedestrian crossings to connect the different areas of the public space. There is even an area for open-air movie projections. Urban art is scattered all over. Today, the area is alive and full of people. The students had direct contact with homeless people, and other interesting people that live in the area.

From there we went to a small pocket forest in the banks of the Pinheiros river (one of the two main rivers of the city). It is a small planting, but a great achievement to call attention to along this polluted, channelized river compressed between two highways. This was an opportunity to teach about the interrelation of riparian forest and watercourses, and the change that car-oriented urbanization has made to it. It was excellent to discuss after the exhibition we had visited the day before.

We crossed the big river by bus and went to visit one of his tributaries, the Iquiririm creek. Its source is hidden behind the wall of the University of São Paulo, where one can see the water falling through a hole in the wall in a jammed, green residual lot. It was a polluted wetland where people dumped garbage until José Bueno and Luiz de Campos discovered it, and began to clean it up and care for it. There was the starting point for Rios e Ruas. Fefa, one of the contributors to this process, was waiting for us there. He was so enthusiastic, telling us the story of Rios e Ruas’ work to recover the stream while he stood over top of the almost-restored wetland. The students got excited and absorbed his love and curiosity. They decided to jump the wall and enter the university to see the other side, where there is a forest that embraces and nourishes the spring. It was an experience that involved all the students and professors, together with José Bueno and Luiz de Campos, who arrived from work just to accompany our group to the discovery of the water source. At that point, things started to amalgamate for the classmates: water, trees and biodiversity, and people! And a better place to live in the city!

When the sun was going down, we went to meet Ricardo Cardim in the largest pocket forest yet planted by Novas Árvores por Aí, together with more than 500 people of all ages. That forest is located at the Candido Portinari Park. They planted Atlantic Forest and also a patch of Cerrado (a Brazilian Savannah ecosystem) that covered part of the original landscape. The native trees were planted in association with a diverse array of edible and flowering plants to attract biodiversity. And they came: we saw lots of birds and insects. We had a surprise: a Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) flew over us. He was going back to Canada. Fortunately, our specialist in birds, Henrique Rajão, was there!

In the third day, we headed to the Praça da Nascente (Headwaters Square—the official name is Homero Silva, but nobody knows why). In fact, Praça da Nascente is now like a small park, whereas a few years ago, it was a place that people dumped garbage; it was derelict, and nobody used to go or even look at it. Andrea Pesek, Lu Cury and the biologist Sandro Von Matter were waiting for us. The sweetness of Andrea hooked everyone. She and Lu told us about the gentle revolution they made and keep making to restore the water sources, and the entire place, reintroducing native flora and fauna. Sandro is responsible for the aquatic fauna that is controlling the mosquitoes in the area. This work was recently highlighted in the headlines of the main newspapers and TV. These caretakers of the park are also legally disputing to block a new real estate development over the water sources. (picture)

It was a kind of magic being there with the students, sitting in the improvised auditorium, where the soundscape consisted of the water flowing as Andrea smoothly told us about the tremendous transformation they had promoted in the landscape and in the neighborhood. (picture)

We also met Daniel Caballero, an artist passionate about Cerrado. He has planted this dry ecosystem vegetation in the slopes of the small park. With his art and planting, he has educated residents, and he is raising awareness about this forgotten ecosystem. It was absolutely incredible to see the regeneration of the green area and to see people strolling up and down the hill, appreciating nature and the small pond in the beginning of fall on a Saturday morning.

At lunchtime, we walked through the Beco do Batman (Batman’s Alley). It is an open-air gallery with astonishing graffiti that attracts visitors from all over the world. Underneath flows the Verde River (Green River), that reappears in heavy rains and can even drag cars, causing a lot of destruction. This neighborhood attracted artists in the 1980s and has become one of the most popular in the city.

After lunch, we went to meet Claudia Visoni, a charismatic urban food gardener (as she likes to call herself). She is a journalist that also overturned her world, abdicating an economically stable life to grow food at the Horta das Corujas (Owls’ Garden, in a small park with the same name). She catalyzed the urban food movement that spread to the entire country, founding the Hortelões Urbanos (Urban Food Growers), now with almost 70,000 members on Facebook. Claudia is a powerful woman that spreads, like a good virus, the idea of living in harmony with nature, in all spheres: producing your own food and cleaning products, consuming only what is absolutely necessary, checking the sources of the products, valuing social relationships, and so on. She is an engaged activist, member of the Regional Environmental Council, and teaches about permaculture and food production (as Nik and Ricardo do about trees and ecosystems). Actually, they work together frequently as activists and doers.

After an inspiring guided tour in the garden that transformed a lifeless lawn into an urban oasis, some students started to work in the field. It was rewarding to watch them work in the soil, cut plants, climb trees, and have a lot fun.

The evening was a surprise. We went to PIPA SP, an urban “beach” in the central area—another public space that was recovered by residents, cleaned, and re-purposed to offer recreation and well-being to all in its new function as a meeting place. While we were there, PIPA SP showed a projection of four short documentaries at the “beach”, by Cine Solar—an itinerant open-air movie theater focused on environmental docs that have already toured around the country. The young group got so excited and enthusiastic with their experience that they started a team called Tribo da Semente (Seed Tribe) to spread what they had experienced and contribute to a better Rio de Janeiro.

On Sundays, Paulista Avenue closes to cars and becomes an urban park. People claim the streets, bikers abound. There was another protest against corruption been organized to happen later in the day, in the same place where it had been three days prior upon our arrival. We started walking along the huge urban space to go back to Trianon Park to meet with Juliana Gatti, founder of the Instituto Árvores Vivas (Alive Trees Institute). She also shifted from her previous professional life because of her passion for trees and urban green areas. The students told us that this second visit to Paulista Avenue was totally different from the first. They could feel, listen, and smell differently as Juliana explained about the trees, accompanied by her husband, the biologist, Sandro (the same who was with us at Praça da Nascente).

We continued the open-air class in the downtown area, where the first public park of São Paulo, the Parque da Luz (Light Park), is located. It has a Romantic design and it was a botanic garden when it was created. There, the trees were different, with many huge and old exotic species. We toured the park, full of people on a sunny day. Juliana has a gift for making people see trees in a sensorial way—not only seeing, but feeling the differences and the role of each one in the urban ecosystem.

We continued our trip with a brief visit to a flyover highway that is also transformed into a park on Sundays, called Minhocão (Big Worm, due to its shape). We went there in part to see the controversial, expensive, and huge green walls built with the funds earned from 800 trees that were cut near the water reservoir in the South zone of the city.

To wrap up with deep social-ecological experience, we went to São Paulo Cultural Center, a special place that gathers arts, culture, and nature in a Modernist building. It houses a library, café, classrooms, and theaters, and has a patch of forest in its center. It also has green roofs that are used as a park, and one of its sides was transformed in an agroforestry experiment where people compost organic residues and produce organic food. The group stayed there until the very last minute, enjoying the fun of people enjoying the open areas: dancing, singing and rehearsing.

A week after we returned to Rio, we had a class in which we asked each student to bring and present a product to express the experience they had. When I asked for them to translate the trip in word, the word was: TRANSFORMATION. I felt so much joy, so rewarded with the outcome. They had been transformed. They wanted to change the city into a place where they would want to live; they were not talking about leaving the city anymore. They were concerned with everyone, and even questioned the Neoliberal way of exploring and depriving people from the feast of the wealthy. They wanted to learn more to be able to plan and design better cities. They were full of energy and desire to contribute to the society in a systemic and holistic manner—not thinking solely about a future job to “make a living”. They were filled with love and inspiration. They wanted to transform their backyards. Yes, in their backyards! (picture)

Cecilia Herzog

Rio de Janeiro

Leave a Reply